Allied invasion of Sicily

| Sicilian Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian Campaign of World War II | |||||||

The U.S. Liberty ship Robert Rowan explodes after being hit by a German bomber off Gela, Sicily, 11 July 1943 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Axis: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Initial Strength: 160,000 personnel 14,000 vehicles 600 tanks 1,800 guns[1] Peak Strength: 467,000 personnel[2] |

230,000 Italian personnel 40,000 - 60,000 German personnel[2][3] 260 tanks 1,400 aircraft[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

24,850 casualties (5,837 killed or missing, 15,683 wounded, 3,330 captured)[5] |

~20,000 casualties[6] 131,359[7]-147,000 killed, wounded or captured (mainly POWs)[6] | ||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||

The Allied invasion of Sicily, codenamed Operation Husky, was a major World War II campaign, in which the Allies took Sicily from the Axis Powers (Italy and Nazi Germany). It was a large scale amphibious and airborne operation, followed by six weeks of land combat. It launched the Italian Campaign.

Husky began on the night of 9–10 July 1943, and ended on 17 August. Strategically, Husky achieved the goals set out for it by Allied planners; the Allies drove Axis air, land and naval forces from the island and the Mediterranean's sea lanes were opened. As a result of the invasion, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was toppled from power in Italy. It opened the way for the invasion of Italy.

Background

Allies

The plan for Operation Husky called for the amphibious assault of the island by two armies, one landing on the South Eastern and one on the central Southern Coast. The amphibious assaults were to be supported by naval gunfire, as well as tactical bombing, interdiction and close air support by the combined air forces. As such, the operation required a complex command structure, incorporating land, naval and air forces. The overall commander was the American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, as Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces North Africa. The British General Sir Harold Alexander acted as his second in command and as the Land Forces / Army Group commander. The American Major General Walter Bedell Smith was appointed as Chief of Staff.[8] The overall Naval Force Commander was the British Admiral Andrew Cunningham.

Land Forces

The Allied land forces were from the American, British and Canadian armies, and were structured as two task forces. The Eastern Task Force (also known as Task Force 545) was led by General Bernard Montgomery and consisted of the British Eighth Army (which included the 1st Canadian Infantry Division). The Western Task Force (Task Force 343) was commanded by Lieutenant General George S. Patton and consisted of the U.S. Seventh Army. The two task force commanders reported to Alexander as Commander of the 15th Army Group.[9]

The Seventh U.S. Army consisted initially of three infantry divisions organized under U.S. II Corps commanded by Major General Omar Bradley. The U.S. 1st Division and U.S. 3rd Division sailed from ports in Tunisia, while the U.S. 45th Division sailed from the United States via Oran in Algeria. The U.S. 2nd Armored Division, also sailing from Oran, was to be a floating reserve and be fed into combat as required. On 15 July, Patton reorganized his command into two corps by creating a new Provisional Corps headquarters commanded by his deputy army commander Geoffrey Keyes.[10]

The British Eighth Army had four infantry divisions and an independent infantry brigade organized under XIII Corps commanded by Lieutenant-General Miles Dempsey and XXX Corps under Lieutenant-General Sir Oliver Leese. The two divisions of XIII Corps (5th Division and 50th Division) sailed from Suez in Egypt. The formations of XXX Corps sailed from more diverse ports: the 1st Canadian Division sailed from the UK, the 51st Division from Tunisia and Malta, and the 231st Independent Infantry Brigade Group from Suez.

The 1st Canadian Infantry Division was included in the Allied invasion of Sicily at the insistence of the Canadian Prime Minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, and the Canadian Military Headquarters in the UK. This request was granted by the British, displacing the veteran 3rd British Infantry Division. The change was not finalized until 27 April 1943, when General Andrew McNaughton, the commanding the First Canadian Army, deemed Husky to be a viable military undertaking and agreed to the detachment of both the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Tank Brigade. The "Red Patch Division" was added to British XXX Corps to become part of the British Eighth Army.[11]

In addition to the amphibious landings, airborne troops were to be flown in to support both the Western and Eastern Task Forces. To the east, the 1st British Airborne Division commanded by Major General George F. Hopkinson were to seize vital bridges and high ground. The initial plan dictated that the American 82nd Airborne Division commanded by Major General Matthew B Ridgway was held as a tactical reserve in Tunisia.[12]

Naval Forces

The Allied naval forces were also grouped into two task forces to transport and support the invading armies. The Eastern Naval Task Force was formed from the British Mediterranean Fleet and was commanded by Admiral Bertram Ramsay. The Western Naval Task Force was formed around the United States Eighth Fleet, commanded by Admiral H. Kent Hewitt. The two naval task force commanders reported to Admiral Cunningham as overall Naval Forces Commander.[9] Two sloops of the Royal Indian Navy - HMIS Sutlej (U95) and HMIS Jumna (U21) - also participated.[13]

Air Forces

At the time of Operation Husky, the Allied air forces in the North African and Mediterranean were organized into the Mediterranean Air Command (MAC) under Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder. The major sub-command of MAC was the Northwest African Air Forces (NAAF) under the command of Lieutenant General Carl Spaatz with headquarters in Tunisia. NAAF consisted primarily of groups from the United States 12th Air Force, 9th Air Force, and the British Royal Air Force (RAF) that provided the primary air support for the operation. Other groups from the 9th Air Force under Lieutenant General Lewis H. Brereton operating from Tunisia and Egypt, and Air H.Q. Malta under Air Vice-Marshal Sir Keith Park operating from the island of Malta, also provided important air support.

The US Army Air Force 9th Air Force's medium bombers and P40 fighters that were detached to NAAF's Northwest African Tactical Air Force under the command of Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham moved to southern airfields on Sicily as soon they were secured. At the time, the 9th Air Force was a sub-command of RAF Middle East Command under Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas. Middle East Command, like NAAF and Air H.Q. Malta, were sub-commands of MAC under Tedder who reported to Eisenhower for NAAF operations[9] and to the British Chiefs of Staff for Air H.Q. Malta and Middle East Command operations.[14][15]

The defenders

The island was defended by the two corps of the Italian 6th Army under General Alfredo Guzzoni, although specially designated Fortress Areas around the main ports (Piazze Militari Marittime), marked as Port Defensive Areas on the map below, were commanded by admirals subordinate to Naval Headquarters and independent of 6th Army.[16] In early July, the total Axis force in Sicily was about 200,000 Italian and 32,000 German troops, and 30,000 Luftwaffe ground staff. The main German formations were the Panzer Division Hermann Göring and the 15th Panzergrenadier Division. The panzer division had 99 tanks in two battalions but was short of infantry (with only three battalions), while the panzergrenadier division had three grenadier infantry regiments and a tank battalion with 60 tanks.[17] About half of the Italian troops were formed into four front-line infantry divisions and headquarters troops; the remainder were support troops or in poor quality immobile coastal divisions and brigades. Guzzoni's defence plan was for the coastal formations to form a covering screen to take the initial impact of an invasion, and allow time for the more centrally located field divisions to intervene.[18]

By late July, the German units had been reinforced, principally by elements of two further divisions (1st Parachute Division and 29th Panzergrenadier Division) and a corps headquarters (XIV Panzer Corps) under General der Panzertruppe Hans-Valentin Hube, bringing the number of German troops to around 70,000.[19] Until the arrival of the corps headquarters, the two German divisions were nominally under Italian tactical control. The panzer division, with a reinforced infantry regiment from the panzergrenadier division to compensate for its own lack of infantry, was under Italian XVI Corps and the rest of the panzergrenadier division under Italian XII Corps.[20] In reality, the German commanders in Sicily were contemptuous of their allies, and German units took their orders from the German liaison officer attached to Italian 6th Army HQ, Generalleutnant Frido von Senger und Etterlin who was subordinate to Albert Kesselring, the German Commander-in-Chief Army Command South (OB Süd). Von Senger had arrived in Sicily in late June as part of a German plan to gain greater operational control of its units.[21] Once Hube arrived, Guzzoni agreed from 16 July to delegate to him control of all sectors where there were German units involved, and from 2 August Hube was given control of the whole Sicilian front.[22]

Planning

At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, with the end of the North African Campaign in sight, the political leaders and the military Chiefs of Staff of the U.S. and Britain met to discuss future strategy. The British Chiefs of Staff were in favour of an invasion of Sicily or Sardinia, arguing that it would force Germany to disperse its forces and might knock Italy out of the war and move Turkey to join the Allies.[23] At first, the Americans opposed the plan as opportunistic and irrelevant, but were persuaded to agree to a Sicilian invasion on the grounds of the great saving to Allied shipping that would result from the opening of the Mediterranean by the removal of Axis air and naval forces from the island.[23]

The Combined Chiefs of Staff appointed General Eisenhower as Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Expeditionary Force, General Alexander as Deputy C-in-C with responsibility for detailed planning and execution of the operation, Admiral of the Fleet Andrew Cunningham as Naval Commander, and Air Chief Marshal Tedder as Air Commander.[24]

The outline plan given to Eisenhower by the Chiefs of Staff involved dispersed landings by brigade and division-sized formations in the south-east, south and north-west areas of the island. The logic behind the plan was that it would result in the rapid capture of key Axis airfields that posed a threat to the beachheads and the invasion fleet lying off them. It would also see the rapid capture of all the main ports on the island, except for Messina, including Catania, Palermo, Syracuse, Licata and Augusta. This would facilitate a rapid Allied build-up, as well as denying their use to the Axis.[25] High level planning for the operation lacked direction because the three main land commanders, Alexander, Montgomery and Patton, were fully occupied in operations in Tunisia. Effort was wasted in presenting plans that Montgomery, in particular, disliked because of the dispersion of forces involved. He was finally able to articulate his objections and put forward alternative proposals on 24 April.[26] Tedder and Cunningham opposed Montgomery's plan because it would leave 13 landing grounds in Axis hands, posing a considerable threat to the Allied invasion fleet.[27] Finally, Eisenhower called a meeting for 2 May with Montgomery, Cunningham and Tedder, in which Montgomery made new proposals to concentrate the Allied effort on the south east corner of Sicily,[27] discarding the intended landings close to Palermo and using the south-eastern ports. After Alexander joined the meeting on 3 May, Montgomery's proposals were finally accepted on the basis that it was better to take an administrative risk (having to support troops by landing supplies across beaches) than an operational one (dispersion of effort).[28][29] Not for the last time, Montgomery had argued a sound course of action, yet done so in a conceited manner, which suggested to others, particularly his American allies, that he was preoccupied with his own interests.[30] In the event, maintaining the armies by landing supplies across the beaches proved easier than expected, partly because of the successful introduction of large numbers of the new amphibious DUKW vehicle. Alexander was later to write "It is not too much to say that the DUKW revolutionised the problem of beach maintenance."[28]

On 17 May, Alexander issued his Operation Instruction No. 1 setting out his broad plan and defining the tasks of the two armies.[28] Broadly speaking, his intention was to establish his armies along a line from Catania to Licata preparatory to a final operations to reduce the island. He later wrote that at that stage it was not practicable to plan further ahead but that his intentions were clear in his own mind what the next step would be: he would drive north ultimately to San Stefano on the northern coast to split the island in two and cut his enemy's east-west communications.[31]

The American Seventh Army was assigned to land in the Gulf of Gela, in south-central Sicily, with 3rd Division and 2nd Armored Division to the west at Licata, site Baia di Mollarella, 1st Division in the center at Gela, and 45th Division to the east at Scoglitti. The U.S. 82nd Airborne Division was assigned to drop behind the defences at Gela and Scoglitti. Seventh Army's beach-front stretched over 50 kilometers (31 mi).

The British Eighth Army was assigned to land in southeastern Sicily. XXX Corps would land on either side of Cape Passero, at the very southeastern corner of Sicily, while XIII Corps would land in the Gulf of Noto, around Avola, off to the north. Eighth Army's beach front also stretched 40 kilometers (25 mi), and there was a gap of some 40 kilometers (25 mi) between the two armies.

Preparatory operations

Once the Axis forces had been defeated in Tunisia, the Allied strategic bomber force commenced attacking the principal airfields of Sardinia, Sicily and southern Italy, industrial targets in southern Italy and the ports of Naples, Messina, Palermo and Cagliari (in Sardinia). The attacks were thus distributed in such a way as to maintain uncertainty as to where the next move of the Allied land forces would be, in order to pin down Axis aircraft and prevent them from being ordered to Sicily. Bombing attacks were stepped up on northern Italy (by aircraft based in the UK) and Greece (by aircraft based in the Middle East).[32] From 3 July, bombing attacks increasingly focused on Sicilian airfields and Axis communications with Italy, although beach defences were left alone to preserve surprise as to exactly where the landings were to take place.[33] By 10 July, only two airfields in Sicily remained fully serviceable and over half the Axis aircraft had been forced to leave the island.[34] Between mid-May and the invasion, allied airmen flew 42,227 sorties that destroyed 323 German and 105 Italian aircraft for the loss of 250 of their own aircraft, mostly to anti-aircraft fire while operating over Sicily.[35]

Heavy air operations were also conducted in May against the small island of Pantelleria, some 70 miles (110 km) south-west of Sicily and 150 miles (240 km) north-west of Malta, to prevent the airfield there being used in support of Axis troops attempting to withdraw from North Africa. From 6 June, attacks were further stepped up and on 11 June, after a naval bombardment and seaborne landing by British 1st Infantry Division (Operation Corkscrew) the island surrendered. The Pelagie Islands of Lampedusa and Linosa, some 90 miles (140 km) west of Malta, followed in short order on 12 June.[34]

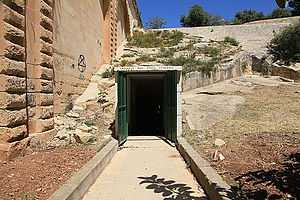

Headquarters

The Allies used a network of underground tunnels and chambers located below the Lascaris Battery in Valletta, Malta (the "Lascaris War Rooms"), for the advance headquarters of the invasion of Sicily.[36] In July 1943, General Eisenhower, Admiral Cunningham, Field Marshal Montgomery, and Air Marshal Tedder occupied the war rooms. Earlier, the war rooms had served as the British headquarters for the defence of Malta.[37]

Deception

To distract the Axis, and if possible divert some of their forces to other areas, the Allies engaged in several deception operations. The most famous and successful of these was Operation Mincemeat. The British allowed a corpse, disguised as a British officer, to drift ashore in Spain carrying a briefcase containing fake secret documents that supposedly revealed that the Allies were planning to invade Greece and Sardinia, and had no plans to invade Sicily. German intelligence accepted the authenticity of the documents with the result that the Germans diverted much of their defensive effort from Sicily to Greece. Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel was sent to Greece to assume overall command. The Germans transferred a group of "R boats" (German minesweepers and minelayers) from Sicily, and laid three additional minefields off the Greek coast. They also moved three panzer divisions to Greece – one from France, and two from the Eastern Front. (The latter move reduced German combat strength against the Russians in the Kursk salient.[38]) Even so, there were a large number of German and Italian soldiers on Sicily when the invasion started. The Germans in particular had soldiers in Sicily that they had withdrawn from North Africa and had not yet reassigned to the Eastern Front.

Battle

Allied landings

Airborne landings

Two British and two American attacks by airborne forces were carried out just after midnight on the night of 9–10 July, as part of the invasion. The American paratroopers consisted largely of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division, making their first combat drop.

The British landings were preceded by the 21st Independent Parachute Company (Pathfinders), who were to mark landing zones for the paratroopers who were intending to seize the Ponte Grande, the bridge over the River Anape just south of Syracuse, and hold it until the British 5th Infantry Division arrived from the beaches at Cassibile, some 7 miles (11 km) to the south.[39] British Glider infantry from the 1st Airlanding Brigade were to seize landing zones inland.[40]

Strong winds of up to 45 miles per hour (72 km/h)[41] blew the troop-carrying aircraft off course and the US force was scattered widely over south-east Sicily between Gela and Syracuse. By 14 July, about two-thirds of the 505th regiment had managed to concentrate,[42] half the US paratroopers failed to reach their rallying points. The British air-landing troops fared little better, with only 12 of the 147 gliders landing on target and 69 crashing into the sea.[43] Nevertheless, the scattered airborne troops maximized their opportunities, attacking patrols and creating confusion wherever possible. A platoon of the South Staffordshire Regiment, who had landed on target, captured Ponte Grande and fought off counterattacks. More men rallied to the sound of shooting, and by 18:30 89 men were holding the bridge.[44] By 11:30, a battalion of the Italian 75th Infantry Regiment from the 54 Infantry Division Napoli arrived with some artillery.[45] The British force held out until about 1530 hours, when they were forced to surrender to Colonel Francesco Ronco's 75th Infantry Regiment[46] only 45 minutes before the leading elements of 5th Infantry Division arrived from the south.[45]

In spite of these mishaps, the widespread landing of airborne troops had an overall positive effect as small isolated units, acting on their own initiative, attacked vital points and created widespread panic.[47]

Seaborne landings

The strong wind also made matters difficult for the amphibious landings, but also ensured the element of surprise as many of the defenders had assumed that no one would attempt a landing in such poor conditions.[47] Landings were made in the early hours of 10 July on 26 main beaches spread along 105 miles (169 km) of the southern and eastern coasts of the island between the town of Licata Torre di Gaffe and Mollarella beach in the west, and Cassibile in the east,[48] with British and Canadian forces in the east and Americans toward the west. This constituted the largest amphibious operation of World War II in terms of size of the landing zone and the number of divisions put ashore on the first day.[49] The Italian defensive plan did not contemplate a pitched battle on the beaches and so the landings themselves were somewhat of an anti-climax.[50] More trouble was experienced from the difficult weather conditions (especially on the southern beaches) and unexpected hidden offshore sandbars than from the Coastal divisions. Some troops landed in the wrong place, in the wrong order and as much as six hours behind schedule[51] but the weakness of the defensive response allowed the Allied force to make up lost time.[47] Nevertheless several Italian coastal units fought well, the 429th Coastal Battalion tasked with defending Gela, losing 45 percent of its men,[52][53] and the attacking US Ranger Battalion losing several men to mines, machinegun and cannon fire.[54] Gruppo Tattito Carmito tasked with defending Malati Bridge, defeated a Royal Marines Commando Battalion on 13 July,[55] and the 246th Coastal Battalion defeated British attempts to capture Augusta on the night of 11–12 July.[56]

Once the Axis commanders had divined the Allies' intentions, the Allies began to see some reaction from the Axis field divisions waiting inland, the Hermann Göring and Livorno Divisions.[57] In the US 1st Infantry Division's sector at Gela, there was a substantial Italian division-sized counterattack at exactly the point where the dispersed 505th Parachute Regiment were supposed to have been. The German Tiger tanks of the Hermann Göring Panzer Division—which had been due to advance with the 4 Infantry Division Livorno—had failed to turn up.[58] Nevertheless, on Highways 115 and 117 during 10 July, Italian tanks of the "Niscemi" Armoured Combat Group and "Livorno" infantry pressed home their attack nearly reaching the Allied position at Gela, but gunfire from the destroyer USS Shubrick and the light cruiser USS Boise destroyed several tanks and dispersed the attacking infantry battalion. The 3rd Battalion, 34th Regiment, "Livorno" Infantry Division, composed mainly of conscripts, is recorded by its commanding officer as having made a valiant but ultimately equally unsuccessful daylight attack in the Gela beachhead two days later alongside infantry and armour of the Hermann Göring Panzer Division.[59]

By the morning of 10 July the Joint Task Force Operations Support System Force captured the port of Licata, at the cost of nearly 100 killed and wounded in the American 3rd Infantry Division, and the division beat off a counterattack from the 538th Coastal Defence Battalion.By 11:30 A.M. Licata was firmly in American hands and the 3rd Infantry had lost fewer than one hundred men. Salvage parties had already partially cleared the harbor,and shortly after noon Truscott and his staff came ashore and set up headquarters at Palazzo La Lumia. About that time the 538th Coastal Defense Battalion, which had been deployed as a tactical reserve, launched a counterattack. By the evening of 10 July, the seven Allied assault divisions—three British, three American and one Canadian—were well established ashore and the port of Syracuse had been captured.[60] Allied firepower proved decisive in the capture of Syracuse, with one Allied war correspondent reporting that:

Large numbers of Italians fought hard and well. The road on which I rode across to Syracuse and beyond proves that. The road to Syracuse was strewn with bodies and shattered pillboxes. Our troops are not winning because of an Italian collapse but because the Allied soldiers are fighting better, with better and more equipment. They are fighting smoothly and efficiently mile by mile — not walking in unopposed.[61]

Fears of an Axis air onslaught had proved unfounded.[62] The preparatory bombing of the previous weeks had greatly weakened the Axis air capability and the heavy Allied presence of aircraft operating from Malta, Gozo and Pantelleria kept most of the Axis attempts at air attack at bay. Some attacks on the first day of the invasion got through, and German aircraft sank the landing ship LST-313 and minesweeper USS Sentinel. Italian Stukas sank the destroyer USS Maddox[63] and the Indian hospital ship Talamba,[64] and in the following days Axis aircraft damaged or sank several more warships, transport vessels and landing craft.[65] Italian Stukas—named Picchiatello in Italian service—and Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 torpedo-bombers coordinated their attacks with the German Junkers Ju 87 and Ju 88 bomber units, and Rome reported as follows on 12 July:[66]

| “ | Italian planes torpedoed three cruisers and one smaller unit and three steamers. Two of them of 8,000 tons each sank. Enemy craft concentrations were attacked by Italian and German formations. Five steamers and several landing craft are reported sunk. Hit and set on fire were more than forty merchantmen and transports of various types. Axis fighters shot down more than thirty enemy planes. Eight more crashed after they were hit by anti-aircraft fire. From operations of the last two days thirteen of our planes and ten of the Germans failed to return. | ” |

As part of the seaborne landings south at Agnone, some 400 men of Lieutenant-Colonel John Durnford-Slater's 3 Commando Brigade captured Malati Bridge on 13 July, only to lose possession of the bridge when Lieutenant-Colonel Francesco Tropea's 4th Self-Propelled Artillery Battalion and the Italian 53rd Motorcycle Company counterattacked.[67][68] The Royal Marines lost 28 killed, 66 wounded and 59 captured or missing[69] in this Italian counterattack.[55]

Exploitation from the beachheads

Alexander's plan was to firstly establish his forces on a line between Licata in the west and Catania in the east before embarking on operations to reduce the rest of the island. Key to this was capturing ports to facilitate the buildup of his forces and the capture of airfields. Eighth Army's tasks were therefore to capture the Pachino airfield on Cape Passero and the port of Syracuse before moving northwards to take the ports of Augusta and Catania. Their objectives also included the landing fields around Gerbini, on the Catania plain. The 7th Army's main objectives included capturing the port of Licata and the airfields of Ponte Olivo, Biscari and Comiso. It was then to prevent enemy reserves from moving eastward against the Eighth Army's left flank.[70]

According to Axis plans, Schmalz Battle Group, under Colonel Wilhelm Schmalz, in conjunction with Major-General Giulio Cesare Gotti-Porcinari's 54th 'Napoli' Infantry Division, was supposed to counterattack any Allied landing on the Augusta-Syracuse coast. But on 10 July, Colonel Schmalz had been unable to contact the Italian division and had proceeded alone towards Syracuse. Unknown to Schmalz, a battalion of 18 Renault R35 tanks, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Massimo d'Andretta from the 'Napoli' Division, broke through the positions held by the 2nd Battalion The Wiltshire Regiment[71] and were only defeated by anti-tank fire after having reached the Priolo and Floridia suburbs of Syracuse.[72]

On the night of 11–12 July, the Royal Navy attempted to capture Augusta, but gunners of the 246th Coastal Battalion repelled the British landing force that was supported by three destroyers.[73] On 12 July, several Italian units took up rearguard positions and successfully covered the withdrawal of the Schmalz Battle Group and the Hermann Göring Division.[74]

Early on 13 July, elements of 5th Division on Eighth Army's right flank—pushing against the delaying tactics of the Schmalz Battle Group—entered Augusta, but not before having been forced to go to ground, when the Germans supported by units of the 'Napoli' Division launched determined counterattacks against the British.[75] On their left, the 50th Division had pushed up Route 114 toward Lentini—15 miles (24 km) northwest of Augusta—and met increasing resistance from R 35 tanks and then infantry from the "Napoli" Division[76] The Canadian Official History of the war later made the erroneous claim that the R 35s from the 'Napoli' were in fact tanks from the Hermann Göring Panzer Division.[77] The commander of the Italian division and his staff were captured, however, by elements of the supporting 4th Armoured Brigade on the 13th[78] and it was not until 18:45 on 14 July that the town had been cleared of obstructions and lurking snipers and the advance resumed.[79] A battalion of the 'Napoli' managed to break through the British lines on the 13th and took up new positions at Augusta, but the continued British advance forced it to retire again on 14 July.[80]

Further left, in the XXX Corps sector, 51st Division had moved directly north to take Palazzolo and Vizzini (30 miles (48 km) west of Syracuse), while the Canadians—having secured Pachino airfield, headed northwest to make contact with the American right wing at Ragusa[81] after having driven off the Italian 122 Infantry Regiment north of Pachino. Canadian war correspondent Ross Munro recorded his experiences of the first few days of the attacks on the 206th Coastal Division in the area of Pachino in a newspaper article printed on 12 July:

Stubborn resistance has been put up by the Italians north and west of Pachino, and along other [Canadian] sectors of the front there were heated engagements. Big battles will probably come before long, but meanwhile large numbers of prisoners are being captured.—The Toronto Globe & Mail, 12 July 1943

The Canadians had captured more than 500 Italian soldiers.[82] Also in the Canadian sector, in the area of Brigadier Robert Edward Laycock's Special Service Brigade, the 206th Coastal Division launched a strong counterattack that threatened to penetrate the area between the Canadians and the Royal Marine Commandos. Fortunately for the British, there was an alert Canadian heavy mortar unit nearby, which broke up the Italian attack.[83]

In the US sector, by the morning of 10 July, the port of Licata had been captured. On 11 July, Patton ordered his reserve parachute troops from the 504th PIR of the 82nd Airborne to drop and reinforce the center. Warning orders had been issued to the fleet and troops on 6, 7, 10 and 11 July concerning the planned route and timing of the drop so that the aircraft would not be fired on by friendly forces.[84] They were intended to drop east of Ponte Olivo (some 5 miles (8.0 km) inland from Gela) to block routes to U.S. 1st Infantry Division's bridgehead at Gela.[39]

However, the 144 Douglas C-47 transports arrived at the time of one of the four main Axis air raids that day on the anchorage and the Allied anti-aircraft gunners were at high alert for targets. The first echelon of troop carrying planes dropped their loads without interference. However, a nervous Allied naval vessel suddenly fired on the formation. Immediately, all the other naval vessels and shore troops joined in, downing friendly aircraft and forcing planeloads of paratroopers to exit far from their intended drop zones. The 52nd Troop Carrier Wing lost 23 of 144 USAAF С-47s to friendly fire; there were 318 casualties with 83 dead.[85] Thirty-seven planes were damaged, while eight returned to base without dropping their parachutists. The 504th PIR suffered 229 casualties to "friendly fire"[86] including 81 dead.[84] In spite of this, the US landings were generally proceeding well and substantial supplies and transport landed to support further offensives. In spite of the failure of the airborne operation, U.S. 1st Infantry Division had taken Ponte Olivo on 12 July and continued north, while U.S. 45th Infantry Division on their right had conformed to them and taken the airfield at Comiso and entered Ragusa to link with the Canadians. On the left, 3rd Infantry Division had pushed troops 25 miles (40 km) up the coast almost to Argento and 20 miles (32 km) inland to Canicatti.[87]

Once the beachheads were secure, Alexander's plan was to split the island in half by thrusting north through the Caltanissetta and Enna region, to deny the central Sicily east-west lateral road. A further push north to Nicosia would cut the next lateral route, and a final push to San Stefano on the north coast would cut the coastal route. Somewhat surprisingly to many commentators, in new orders issued on 13 July,[88] he gave this task to Eighth Army, perhaps based on a somewhat over-optimistic situation report by Montgomery on late on 12 July,[89] while U.S. 7th Army were to continue their holding role on Eighth Army's left flank despite what appeared to be an opportunity for them to make a bold offensive move.[90]

On 12 July, Albert Kesselring had visited Sicily and formed the opinion that German troops were fighting virtually on their own. As a consequence, he concluded that the German formations needed to be reinforced, and that western Sicily should be abandoned in order to shorten the front line. The immediate priority was first to slow and then halt the Allied advance, to which end a defence line was to be formed running from San Stefano on the north coast, through Nicosia, Agira, Cantenanuova and from there to the eastern coast south of Catania.[91] This line was the Hauptkampflinie.[92]

While XIII Corps continued to push along the Catania road, XXX Corps were directed north along two routes; the first was an inland route through Vizzini, and the second following Route 124, which cut across U.S. 45th Infantry's front and necessitated its return to the coast at Gela for redeployment behind 1st Infantry Division. But progress was slow. The Schmalz battlegroup from the Hermann Göring Division continued to skilfully delay 5th Infantry Division, allowing time for the two regiments from the 1st Parachute Division flying in to Catania to deploy. Resistance in the British sector stiffened as German units reorganised on the new defensive plan.[93] On 12 July, 1 Parachute Brigade had been dropped to capture the Primasole Bridge over the river Simeto on the southern edge of the Catania plain and the British paratroopers managed to hold it open against fierce attacks from seven Italian battalions,[94] until 5th Infantry Division moved north to join them. The 5th Division, delayed by strong opposition, made contact early on 15 July, but it was not until 17 July that a shallow bridgehead north of the river was consolidated.[88]

On 16 July, the Sicilian air command ordered the evacuation back to Italy of all surviving Italian aircraft at airfields in Calabria and Puglia. About 160 Italian aircraft had been lost in the first week of the invasion, 57 of which were lost to Allied fighters and anti-aircraft fire from 10–12 July alone.[95] That same day, the British aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable was damaged by an Italian torpedo bomber[96][97] and the Italian submarine Dandolo torpedoed the British cruiser HMS Cleopatra[98] and put her out of action for the remainder of the European conflict.

On the night of 17 July, the Italian light cruiser Scipione Africano, equipped with the Italian-developed EC.3 Gufo radar,[99] detected and engaged four British Elco motor torpedo boats lurking 5 miles (8 km), while passing the Strait of Messina at high speed. She sank MTB 316 and heavily damaged MTB 313 between Reggio di Calabria and Pellaro, on the position 38°3′20.20″N 15°35′28.35″E / 38.0556111°N 15.5912083°E.[100][101][102] Twelve British seamen lost their lives in this action.[103]

On the night of 17/18 July, Montgomery renewed his attack toward Catania using two brigades from 50th Division. They met strong opposition, and by 19 July Montgomery decided to call off the attack and instead increase the pressure on his left. The 5th Division attacked on 50th Division's left but with no greater success, and on 20 July the 51st Division, further west, crossed the river Dittaino at Sferro and made for the Gerbini airfields. They too were driven back by counterattacks on 21 July.[104]

On Eighth Army's far left flank, the Canadians continued their wide sweep; but it was becoming clear that, as German units settled into their new positions in north eastern Sicily, the Army would not have sufficient strength to carry the whole front. As a consequence, the Canadians were ordered to continue north to Leonforte and then turn eastward to Adrano on the southwestern slopes of Mount Etna, thus abandoning the originally planned encirclement of Mount Etna using Route 120 to Randazzo. At the same time, Montgomery called forward from North Africa his reserve division, 78th Infantry Division.[104]

Meanwhile, Patton had reorganised his forces into two Corps. By 17 July, the Provisional Corps on his left had captured Porto Empedocle and Agrigento, and II Corps on his right took Caltanissetta on 18 July, just short of Route 121, the main east-west lateral through the center of Sicily. The U.S. advance toward Agrigento was temporarily held up by the 207th Coastal Defence Division[105] and the 10th Bersaglieri Regiment under Colonel Fabrizio Storti had forced Colonel William Darby's 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions to fight their way into Agrigento, a city of 34,000. Resistance was stiff enough to require house-to-house combat fighting,[106] but by late afternoon on 16 July, the city was in American hands. According to historian Samuel Eliot Morison, "The Italians fought manfully for Agrigento."[107]

However, the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division managed to scramble across 7th Army's front to join the other German formations in the east of the island and so little real resistance was now expected in the west. Patton was therefore ordered on 18 July to push troops north through Petralia on Route 120, the next east-west lateral, and then to cut the northern coast road. He would then embark on mopping up the west of the island. II Corps were given the task of making the northward move, while the Provisional Corps was tasked with the mopping up operation. Against a background of good progress, Alexander issued further orders to Patton to develop an eastward threat along the coast road once he had cut it. He was also directed to capture Palermo as quickly as possible in order to create a main supply base to maintain further eastward commitment north of Mount Etna.[104]

On 21 July, the Seventh US Army's Provisional Corps overran Ragruppamento Schreiber and several battalions from the Aosta and Assietta Divisions tasked with protecting the Italian withdrawal,[108] but Patton lost 300 men killed and wounded in the process.[109]

On 22 July, the Provisional Corps entered Palermo[110] and the next day 45th Division cut the north coast road. These achievements—during which 7th Army took 19,000 prisoners—were considerable feats, with troops having to march considerable distances in sweltering damp heat.[111]

Battles for Etna positions

During the last week in July, Montgomery gathered his forces to renew the attack on 1 August. His immediate objective was Adrano, the capture of which would split the German forces on either side of Mount Etna. During the week, the Canadians and 231st Brigade continued their eastward push from Leonforte, and on 29 July had taken Agira, some 15 miles (24 km) west of Adrano. On the night of 29 July, 78th Division with 3rd Canadian Brigade under command, took Catenanuova and made a bridgehead across the river Dittaino. On the night of 1 August, they resumed their attack to the northwest toward Centuripe, an isolated pinnacle of rock, which was the main southern outpost of the Adrano defences. After heavy fighting against the Hermann Göring Division and the 3rd Parachute Regiment all day on 2 August, the town was finally cleared of defenders on the morning of 3 August. The capture of Centuripe proved critical, in that the growing threat to Adrano made the position covering Catania untenable.[111]

Meanwhile, Patton had decided that his communications could support two divisions pushing east, 45th Division on the coast road and 1st Division on Route 120. In order to maintain the pressure, he relieved 45th Division with the fresher 3rd Division and called up 9th Infantry Division from reserve in North Africa to relieve 1st Division.[111]

Axis forces were now settled on a second defensive line, the Etna Line, running from San Fratello on the north coast through Troina and Aderno. On 31 July, 1 Division with elements of the arriving 9th Division attached, reached Troina and the Battle of Troina commenced. This important position was held by the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. The remnants of the 28 Infantry Division Aosta in the form of four battalions[112][113] had also been pulled back to Troina to assist in the defensive preparations and forthcoming battle. For six days, the Germans and Italians stubbornly defended the position inflicting and taking heavy casualties. During the battle, they launched 24 medium-scale counterattacks and countless smaller local ones, in one of which Lieutenant-Colonel Giuseppe Gianquinto's 1st Battalion, 5th Regiment of the 'Aosta' managed to take 40 American prisoners.[114][115] But, by 7 August, the U.S. 18th Infantry Regiment had captured Mount Pellegrino, which overlooked the Troina defences, allowing accurate direction of Allied artillery. The defenders' left flank was also becoming exposed as the adjacent Hermann Göring Division was pushed back by XXX Corps, and as a result they were ordered to withdraw that night in phases to the defensive positions of the Tortorici Line.[116]

Elements of 29th Panzergrenadier Division and 26th Assietta Infantry Division,[117] the Italians allocated "the most exposed section" of the Italo-German position,[118] were also proving difficult to dislodge on the coast at Santa Agata and San Fratello. Patton sent a small amphibious force behind the defences, which led to the fall of Santa Agata on 8 August after holding out for six days,[111] thanks in large part to the 25th Artillery Regiment of the Assietta Division.[119]

Meanwhile, on 3 August, XIII Corps—taking advantage of the fluidity caused by the threat to Adrano—resumed their advance on Catania, and by 5 August the town was in their hands. Adrano itself continued to resist, but fell to 78th Division on the night of 6 August,[111] while on their right, 51st Division took Biancavilla, 2 miles southeast of Adrano. After the fall of Adrano, the Canadian Division was withdrawn into Army Reserve.[120] On 8 August, 78th Division—moving north from Adrano—took Bronte and 9th Division, advancing from Troina, took Cesaro – both key positions on the New Hube Line. Both divisions were converging on Randazzo, on the northwest slopes of Etna. Randazzo fell on 13 August and 78th Division was taken into reserve.[111] As the Allied advance continued, their front line shortened and Montgomery decided to withdraw XIII Corps HQ and 5th Infantry Division on 10 August to allow them to prepare for the planned landings on mainland Italy.[121]

On the northern coast, the 3rd Division continued to meet strong resistance and difficulties created by extensive demolition of the road. Two more end-run amphibious attacks, and the rebuilding efforts of the engineers, kept the advance moving.[122] Although Kesselring had already decided to evacuate, the Axis forces continued their delaying tactics, assisted by the favorable defensive terrain of the Messina Peninsula. On the night of 16 August, the leading elements of 3rd Division finally entered Messina.[123]

Axis evacuation

By 27 July, the Axis commanders had realised that the outcome of the campaign would be an evacuation from Messina.[124] Kesselring reported to Hitler on 29 July that an evacuation could be accomplished in three days and initial written plans were formulated dated 1 August.[125] However, when Hube suggested on 4 August that a start should be made by transferring superfluous men and equipment, Guzzoni refused to sanction the idea without the approval of the Comando Supremo. The Germans nevertheless went ahead, transferring over 12,000 men, 4,500 vehicles and 5,000 tons of equipment from 1–10 August.[126] On 6 August, Hube suggested to Guzzoni, via von Senger, that HQ 6th Army should move to Calabria. Guzzoni rejected the idea but asked if Hube had decided to evacuate Sicily. Von Senger replied that Hube had not.[127] The next day, Guzzoni learned of the German plan for evacuation and reported to Rome of his conviction of their intentions. On 7 August, Guzzoni reported that, without German support, any last ditch stand would only be short. On 9 August, Rome ordered that Guzzoni's authority should be extended to Calabria and that he should transfer some forces there to reinforce the area. On 10 August, Guzzoni informed Hube that he was responsible for the defence of northeast Sicily and that Italian coastal units and the Messina garrison were under his command. Guzzoni then crossed to the mainland with 6th Army HQ and 16th Corps HQ, leaving Admiral Pietro Barone and Admiral Pietro Parenti to organise the evacuation of the remains of the Livorno and Assietta divisions (and any other troops and equipment that could be saved).[128]

Key to the German plan's success was its thoroughness and clear lines of command imposing strict discipline on the operation. Colonel Ernst-Günther Baade was the German Commandant Messina Straits with Fortress Commander powers, including control over infantry, artillery, anti-aircraft, engineer and construction, transport and administration units as well as German naval transport headquarters.[129] On the mainland, Generalmajor Richard Heidrich, who had remained in Calabria with his 1st Parachute Division headquarters and the 1st Parachute Regiment when the rest of the division had been sent as reinforcements to Sicily, was appointed XIV Panzer Corps Mainland Commander to receive evacuating formations, while Hube continued to control the operations on the island.[130]

Full-scale withdrawal began on 11 August and continued to 17 August. During this period, Hube ordered successive withdrawals each night of between 5 and 15 miles (8.0 and 24.1 km), keeping the following Allied units at arm's length with the use of mines, demolitions and other obstacles.[131] As the peninsula narrowed, shortening his front, he was able to withdraw units for evacuation.[132] The Allies attempted to counter this by launching brigade-sized amphibious assaults, one each by 7th and 8th Armies, on 15 August. However, the speed of the Axis withdrawal was such that these operations "hit air".[133]

The German and Italian evacuation schemes proved highly successful. The Allies were not able to prevent the orderly withdrawal nor effectively interfere with transports across the Strait of Messina. The narrow straits were protected by 120 heavy and 112 light anti-aircraft guns.[134] The resulting overlapping gunfire from both sides of the strait was described by Allied pilots as worse than over the Ruhr,[123] making daylight air attacks highly hazardous and generally unsuccessful. Night attacks were less hazardous, and there were times when air attack was able to delay and even suspend traffic across the straits. However, when daylight returned, the Axis were able to clear the backlog from the previous night.[135] Nor was naval interdiction any more practicable. The straits varied from 2–6 miles (3.2–9.7 km) wide and were covered by artillery up to 24 centimeters (9.4 in) in caliber. This, combined with the hazards of a 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph) current, made risking warships unjustifiable.[134] Furthermore, there were real fears, among some senior Allied naval commanders, that Italian warships were preparing to intervene and clear the Straits of Messina in a suicide run.[136][137]

On 18 August, the German High Command recorded that 60,000 troops had been recovered. The equivalent Italian figure, according to the British official History of the Second World War was about 75,000.[138] Barbara Tomlin, a naval historian, provides more accurate details and says the Italians evacuated 62,182 men, 41 guns and 227 vehicles from Sicily with the loss of only one motor raft and the train ferry Carridi, which failed to escape and had to be scuttled when Allied troops entered Messina.[139] In reality, the Germans evacuated some 52,000 troops (including 4,444 wounded), 14,105 vehicles, 47 tanks, 94 guns, 1,100 tons of ammunition, and about 20,700 tons of gear and stores.[140]

Aftermath

The Sicily campaign had cost the Allies nearly 25,000 casualties. The U.S. 7th Army lost 8,781 men (2,237 killed or missing, 5,946 wounded, and 598 captured), while the British 8th Army suffered 11,843 casualties (2,062 killed or missing, 7,137 wounded and 2,644 captured). In addition, the U.S. Navy lost 546 killed or missing and 484 wounded and the Royal Navy lost 314 killed or missing, 411 wounded and four captured. The USAAF also reported 28 killed, 88 missing and 41 wounded.[141] Canadian forces had suffered 2,310 casualties, including 562 killed, 1,664 wounded, and 84 captured.[141][142]

According to historians Samuel W. Mitcham and Friedrich Von Stauffenberg, German units lost about 20,000 killed, wounded or captured,[141] although military historian Manfred Messerschmidt [et al.] reported that the German forces lost 4,678 men killed, 5,532 captured and 13,500 wounded, making up a total of 23,710 German casualties.[143] Italian military losses are reported to be 4,325 killed, 32,500 wounded and 116,681 captured[7] and authors widely concur with the number of Italians believed to have be taken prisoner to be around 100,000.[144][145][146] In 2007, Mitcham and Von Stauffenberg raised this estimate to 147,000.[6] An earlier Canadian study of the Allied invasion, estimated the total number of Italian and Germans taken prisoner in Sicily to be around 100,000.[142]

The Allied command was forced to improve interservice coordination, particularly with regard to the use of airborne forces. After several misdrops and the deadly "friendly fire" incident of 11 July, increased training and some tactical changes kept the paratroopers in the war. Indeed, a few months later, the initial assessment of the Operation Overlord plan included a request for four airborne divisions.

After the capture of Biscari airfield on 14 July, American soldiers from the 180th Regimental Combat Team, 45th Division[147] executed 74 Italian and two German prisoners of war during two separate massacres at Biscari airfield in July–August 1943.[148] Sergeant Horace T. West and Captain John T. Compton were each charged for committing a war crime; West was convicted and sentenced to life in prison and stripped of his rank, but was released as a private. Compton was charged with killing 40 prisoners in his charge but was acquitted and transferred to another regiment, where he died a year later in the fighting in Italy.[149]

Constituent operations

- Operation Barclay/Operation Mincemeat: Deception operations aimed at misleading Axis forces as to the actual date and location of the Allied landings.

- Operation Corkscrew: Allied invasion of the Italian island Pantelleria on 10 June 1943.

- Operation Ladbroke: Glider landing at Syracuse on 9 July 1943.

- Operation Narcissus: Commando raid on a lighthouse near the main landings on 10 July 1943.

- Operation Chestnut: Advanced air drop by 2 SAS to disrupt communications on 12 July 1943.

- Operation Fustian: Airborne landing at Primosole Bridge ahead on 13–14 July 1943.

See also

References

Explanatory notes

Citations

- ↑ Mitcham & von Stauffenberg (2007), p. 63

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mitcham & von Stauffenberg (2007), p. 307

- ↑ Shaw, p.119

- ↑ Dickson(2001) p. 201

- ↑ Mitcham & von Stauffenberg (2007), pp. 305–306

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Mitcham & von Stauffenberg (2007), p. 305

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Le Operazioni in Sicilia e in Calabria (Luglio-Settembre 1943), Alberto Santoni, p.401, Stato maggiore dell'Esercito, Ufficio storico, 1989

- ↑ D'Este Appendix B

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 D'Este Appendix A

- ↑ Molony, p. 108.

- ↑ Copp (2008), pp.5–42

- ↑ Molony, pp. 26, 27.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (30 November 2011). World War II at Sea: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1 (2011 ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 374. ISBN 9781598844573. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ↑ Craven, Wesley F. and James L. Cate. The Army Air Forces in World War II, Volume 2, Chicago, Illinois: Chicago University Press, 1949 (Reprinted 1983, ISBN 0-912799-03-X).

- ↑ Richards, D. and H. Saunders, The Royal Air Force 1939–1945 (Volume 2, HMSO, 1953)

- ↑ Molony, p. 40

- ↑ Molony, pp. 41–42

- ↑ Alexander, p. 1010

- ↑ Molony, p. 122

- ↑ Molony, p. 43

- ↑ Molony, p. 41

- ↑ Molony, p.44

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Molony, p. 2

- ↑ Molony, p. 3

- ↑ Molony, pp. 13–18

- ↑ Molony, p. 21

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Molony, p. 23

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Alexander, p. 1013

- ↑ Molony, pp. 23–24

- ↑ Molony, p. 24.

- ↑ Alexander, p. 1014

- ↑ Molony, p. 32

- ↑ Molony, p. 33

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Molony, p. 49

- ↑ Zuehlke, p. 90

- ↑ Holland (2004), p.416.

- ↑ Holland (2004), p. 170.

- ↑ Zabecki, David T. (1995). "Operation Mincemeat". World War II Magazine (November 1995).

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Molony, p. 83

- ↑ Hoyt (2007), p. 12

- ↑ Hoyt (2007), p. 21

- ↑ Molony, pp. 81–82

- ↑ Molony, pp. 79–80

- ↑ Molony, p. 8.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Molony, p. 81

- ↑ Mitcham & von Stauffenberg (2007), p. 75

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Alexander, p. 1018

- ↑ Molony, p. 55.

- ↑ Birtles, p. 24.

- ↑ Molony, p. 52.

- ↑ Carver, p31

- ↑ "Although the Italians were not as well trained or disciplined as the elite Rangers, they fought courageously for four hours before being overwhelmed. The 429th suffered 45 percent casualties, including 5 officers killed and 4 wounded and 185 enlisted men killed or wounded. The Rangers took 200 prisoners when the garrison finally surrendered at about 8 A.M." The Battle of Sicily: How the Allies Lost Their Chance for Total Victory, Samuel W. Mitcham, Friedrich Von Stauffenberg, p. 89, Stackpole Books, 2007

- ↑ "The 429th Coastal Battalion lost 45 percent of its men." A Military History of Italy, Ciro Paoletti, p. 184, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008

- ↑ "So swift was the Ranger advance across the soft sand and so strong was the momentum of their surging bodies that when the first explosion of a buried land mine blew Lieutenant Wojcik into shredded bits, most of D Company had already entered the minefield. Four riflemen following Wojcik were also killed. The lieutenant leading the first platoon was blinded by shrapnel. Machine-gun fire cut down others. A blast that tossed Sergeant Randall several feet ripped open his abdomen. Covering the gaping gash with his cartridge belt, he struggled to his feet and led the remnants of the company up a steep embankment to a dirt road that ran parallel to a cliff topped by pillboxes and machineg gunners. Without pause, Randall reached one pillbox, and flung in a hand grenade, silencing the cannon within. He raced down the road to join Andre. By leapfrogging between pillboxes they took out seven and killed twenty Italians. When the fighting was over, a lieutenant saw how seriously Randall had been wounded and called for men to take him to a first-aid station. "Hell no," Randall exclaimed. "I'm not helpless yet. Get me prisoners to guard, or something." For his heroic actions he was given a battlefield promotion to second lieutenant and the Distinguished Service Cross." Onward We Charge: The Heroic Story of Darby's Rangers in World War II, H. Paul Jeffers, p. ?, Penguin, 2007

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "The Commando unit's actions on the coast drew the attention of the Axis, and on 14 July, Tactical Group "Carmito", consisting of the 4th Battalion Semovente da 47/32 and the 53rd Motorcycle Company under Lieutenant-Colonel Tropea, attacked the Commandos with the help of three German tanks and some Paratrooopers." Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini's Wars, 1935-1943, Patrick Cloutier, p. 193, Lulu, 2013

- ↑ "12 July saw the firmly-established Americans expanding from their beachheads, as the flow of supplies and reinforcements increased: the British consolidated their gains south of Syracuse, and prepared for offensive action toward the ports of Augusta and Catania. The latter had attempted to get a landing force past the harbor defences of Augusta on the night of 11/12 July, but those members of the 246th Coastal Battalion who remained at their guns turned back the effort, which was made by one Greek and two British destroyers ... the shore batteries delayed a British takeover of Augusta by two days." Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini's Wars, 1935-1943, Patrick Cloutier, p. 191, Lulu, 2013

- ↑ Molony, pp. 55–64.

- ↑ Follain (2005), p. 130

- ↑ Gazzi, Alessandro. "Flesh vs. Iron: 3rd Battalion, 34th Regiment, "Livorno" Infantry Division in the Gela Beachhead counterattack: Sicily, 11 July-12th, 1943". Comando Supremo, Italy at War website. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ↑ Molony, p. 60.

- ↑ The Western Australian, 15 July 1943

- ↑ Molony, p. 64.

- ↑ Junkers Ju87 over the Mediterranean, John A Weal, p. 53, Delprado Publishers/Ediciones de Prado, 1996

- ↑ "Witness Describes Hospital Ship Loss; Injured Paratrooper Relates How Italian Plane Bombed Fully Lighted Talamba", The New York Times, 19 July 1943

- ↑ Bauer, Eddy; Kilpi, Mikko (1975). Toinen maailmansota : Suomalaisen laitoksen toimituskunta: Keijo Mikola, Vilho Tervasmäki, Helge Seppälä. 4 (in Finnish). Helsinki: Werner Söderström. ISBN 951-0-05844-0.

- ↑ The New York Times (Tuesday, 13 July 1943): page 2

- ↑ Sicily, Hugh Pond, p. 128, Kimber, 1962

- ↑ Zuehlke, p. 183

- ↑ 3 Commando Bridge

- ↑ Molony, p. 77.

- ↑ The Battle for Sicily: Stepping Stone to Victory, Ian Blackwell p. 116, Pen & Sword Military, 24 July 2008

- ↑ Sicily, Hugh Pond, p. 117, Kimber, 1962

- ↑ "12 July saw the firmly-established Americans expanding from their beachheads, as the flow of supplies and reinforcements increased: the British consolidated their gains south of Syracuse, and prepared for offensive action toward the ports of Augusta and Catania. The latter had attempted to get a landing force past the harbor defences of Augusta on the night of 11/12 July, but those members of the 246th Coastal Battalion who remained at their guns turned back the effort, which was made by one Greek and two British destroyers ... the shore batteries delayed a British takeover of Augusta by two days. " Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini's Wars, 1935-1943, Patrick Cloutier, p. 191, Lulu, 2013

- ↑ "On 12 July, an Axis retreat began all along the line, with the Allies advancing close behind. The U.S. advance toward Cancinatii was temporarily held up by a group of Semovente da 90/53. Group Schmalz retreated toward Catania. The 246th Coastal Brigade, which had been holding off British tanks, was ordered to retreat to strongpoints at Cozzo Telegrafo and Acquedolci. The Napoli Division's 76th Regiment covered the left flank of Schmalz's Germans, who were withdrawing toward Lentini; soon the reunited battalions of Napoli's 76th Regiment were ordered to withdraw to Palermo ... The Hermann Göring Division was tardily withdrawing from the Piano Lupo area toward Caltagirone, and the Livorno Division was refusing its right flank in a withdrawal toward Piazza Armerina, in a move meant to cover the Hermann Göring Division." Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini's Wars, 1935-1943, Patrick Cloutier, p. 193, Lulu, 2013

- ↑ The Battle of Sicily: How the Allies Lost Their Chance for Total Victory, Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Friedrich Von Stauffenberg, p.140, Stackpole Books, 10 June 2007

- ↑ Rissik, David (1953). The D.L.I. at War: The History of the Durham Light Infantry, 1939–1945. Durham Light Infantry. p. 123.

- ↑ Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War: The Canadians in Italy, 1943–1945, G. W. L. Nicholson, p. 85, R. Duhamel, Queen's Printer, 1966

- ↑ Carver, R.M.P. (1945). "Chapter 4: Sicily, Italy and Home – June 1943 to June 1944". History of 4th Armoured Brigade.

- ↑ Molony, p. 94.

- ↑ History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 9: Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, January 1943 – June 1944, Samuel Eliot Morison, p.163, University of Illinois Press, 1 March 2002

- ↑ Molony, p. 82.

- ↑ Pachino Day: The RCR Lands in Sicily, 10 July 1943

- ↑ The Battle of Sicily: How the Allies Lost Their Chance for Total Victory, Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Friedrich Von Stauffenberg, p. 80, Stackpole Books, 10 June 2007

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Molony, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Carafano, James Jay (2006). "A Serious Second Front". GI ingenuity: improvisation, technology, and winning World War II. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 100. ISBN 0-275-98698-5.

It was one of the most deadly cases of "friendly fire" in the American war to date. Allied guns brought down twenty-three C-47 transport aircraft. There were 318 casualties with 83 dead.

- ↑ Hoyt (2007), p. 29

- ↑ Molony, p. 86.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Alexander, p. 1019.

- ↑ Molony, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Molony, p. 89.

- ↑ Molony, p. 91.

- ↑ Molony, p. 92.

- ↑ Molony, p. 93.

- ↑ Stern Fight for a Bridge on Catania Plain

- ↑ Italian Aces of World War 2, Giorgio Apostolo, p. 25, Osprey Publishing, 25 November 2000

- ↑ "The 29,730-ton (full load) aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable was providing air cover for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, in July 1943. On 16 July, just after midnight, her crew detected the sound of an approaching aircraft. From its engine note and its approach towards the stern of the carrier they took it to be one of their own Albacore torpedo bombers returning to the ship in difficulty. However, the aircraft then dropped something into the sea about 300yds off the port beam, opened up and flew directly across the flight deck just in front of the bridge. The object dropped was seen to be a torpedo, running on the surface, and the order was given to go full ahead and come hard to port to comb its track. When it was 50yds from the ship, it dived, and hit her on the port side amidshps, where the port side hull had been widened asymmetriclally to offset the weight of the island to starboard. Observers confirmed that the aircraft which had carried out the daring attack had been Italian." Torpedo: The Complete History of the World's Most Revolutionary Naval Weapon, p. 197, Roger Branfill-Cook, Seaforth Publishing, 27 Aug 2014.

- ↑ AIRCRAFT CARRIER WARFARE, Part 3 of 3 - 1943-45

- ↑ Submarines of World War II, John Ward, p. 50, Zenith Imprint, 1 October 2001

- ↑ Swords, Séan: Technical history of the beginnings of radar. Volume 6 of History of technology series Radar, Sonar, Navigation and Avionics. P. Peregrinus on behalf of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, 1986, page 129. ISBN 0-86341-043-X

- ↑ Pope, Dudley: Flag 4: The Battle of Coastal Forces in the Mediterranean 1939-1945. Chatham Publishing, 1998, pp. 121-122. ISBN 1-86176-067-1

- ↑ Fioravanzo, Giusseppe (1970). Le Azioni Navali in Mediterraneo Dal 1° aprile 1941 all'8 settembre 1943. USMM, pp. 468-469 (Italian)

- ↑ Baroni, Piero (2007). La guerra dei radar: il suicidio dell'Italia : 1935/1943. Greco & Greco, p. 187. ISBN 8879804316 (Italian)

- ↑ Naval-History.net

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Alexander, p. 1020.

- ↑ "The 207th Coastal Defence Division, under Colonel de Laurentis, which now consisted mostly of Tactical Group Chiusa-Sciafani and a Blackshirt unit, stalled the American advance to Agrigento." Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini's Wars, 1935-1943, Patrick Cloutier, p. 194, Lulu, 2013

- ↑ Tomblin (2004), p. 206

- ↑ History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 9: Sicily-Salerno-Anzio, January 1943 – June 1944, Samuel Eliot Morison, p.176, University of Illinois Press, 1 March 2002

- ↑ "One by one, the small Italian mobile groups were overwhelmed. Group Schreiber was overrun and destroyed by American tanks near Alimena on July 21, and Patton's spearheads barrelled into the rear of the retreating Assietta and Aosta Divisions, destroying the Aosta's mortar battalion and overrunning several battalions of infantry. The 48th (Assietta) Artillery Regiment escaped with only one gun." Blitzkrieg No Longer, Samuel Mitcham, p. 185, Pen and Sword, 2010

- ↑ "Patton's men moved away from their landing areas and toward their interim objective of Palermo. Patton turned to a trusted subordinate general, Geoffrey Keyes, whom he appointed his deputy Seventh Army commander. He assigned Keyes to lead both 2nd Infantry and 2nd Armored Divisions on a very fast ride of 100 miles in only a few days. The result was 300 American casualties and enemy casualties numbering 6,000." I Was With Patton, D. A. Lande, p. 81, Zenith Imprint, 2002

- ↑ Video: American Bombers Smash Axis Oil Fields In Romania Etc. (1943). Universal Newsreel. 1943. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 111.3 111.4 111.5 Alexander, p. 1021.

- ↑ The Battle for Sicily: Stepping Stone to Victory, Ian Blackwell, p. 181, Pen & Sword Military, 24 July 2008

- ↑ "Four battalions from the Aosta's 5th and 6th Regiments were on hand to support the German defence of Troina." Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini's Wars, 1935-1943, Patrick Cloutier, p. 200, Lulu, 2013

- ↑ Mitcham & von Stauffenberg (2007), p. 263

- ↑ "For his leadership n this action, Lieutenant Colonel Gianquinto was awarded the Iron Cross by the Germans. His battalion returned from this combat with only 170 men. Ultimately, its parent formation—the 5th Regiment— would cross the Straits of Messina to Calabria with only 600 men, while the 6th Regiment would make it across with only 700 men." Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini's Wars, 1935-1943, Patrick Cloutier, p. 201, Lulu, 2013

- ↑ Mitcham & von Stauffenberg (2007), p. 264

- ↑ SICILY, Sarasota Herald-Tribune, 3 August 1943

- ↑ Ring of Steel Thrown Around Foe In Sicily, St. Petersburg Times, 4 August 1943

- ↑ "The Axis units held their positions through several days of attack, much thanks due to Italian artillery support." The Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini's Wars, 1935-1943, Patrick Cloutier, p. 202, Lulu, 2013

- ↑ Molony, p. 174.

- ↑ Molony, p. 177.

- ↑ Alexander, pp. 1021–1022.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Alexander, p. 1022.

- ↑ Molony, p. 163.

- ↑ Molony, p. 164.

- ↑ Molony, p. 166.

- ↑ Molony, p. 175.

- ↑ Molony, pp. 175–176.

- ↑ Molony, p. 165.

- ↑ Molony, p. 112n.

- ↑ Molony, p. 180.

- ↑ Molony, p. 167.

- ↑ Molony, p. 181.

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 Molony, p. 168.

- ↑ Molony, p. 179.

- ↑ Mussolini's War: Fascist Italy's Military Struggles from Africa and Western Europe to the Mediterranean and Soviet Union 1935–45, Frank Joseph, p. 176, Casemate Publishers, 19 April 2010

- ↑ Years of Expectation: Guadalcanal to Normandy, Henry H. Adams, p. 127, New York, McKay, 1973

- ↑ Molony, 182.

- ↑ With Utmost Spirit: Allied Naval Operations in the Mediterranean, 1942–1945, Barbara Tomlin, p. 227, University Press of Kentucky, 8 October 2004

- ↑ Rommel's Desert Commanders: The Men Who Served the Desert Fox, North Africa, 1941–1942, Samuel W. Mitcham, p. 80, Greenwood Publishing Group, 28 February 2007

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 141.2 The Battle of Sicily: How the Allies Lost Their Chance for Total Victory, Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Friedrich Von Stauffenberg, p. 305, Stackpole Books, 10 June 2007

- ↑ 142.0 142.1 Decisive Decades: A History of the Twentieth Century for Canadians, A. B. Hodgetts, J. D. Burns, p. 354, T. Nelson & Sons (Canada), 1973

- ↑ Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg, Manfred Messerschmidt, et al, p. 1114, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2007

- ↑ Voices of My Comrades: America's Reserve Officers Remember World War II, Carol Adele Kelly, p. 159, Fordham Univ Press, 15 December 2007

- ↑ Silent Wings at War: Combat Gliders in World War II, John L. Lowden, p. 55, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1 May 1992

- ↑ World War II Companion, David M. Kennedy, p. 550, Simon and Schuster, 2 October 2007

- ↑ La Guerra in Sicilia 1943: Storia Fotografica, Ezio Costanzo, p.130, Le Nove Muse, 2009

- ↑ The Greatest War: Americans in Combat, 1941–1945, Gerald Astor, p.333, Presidio, 1 December 1999

- ↑ Le altre stragi: le stragi alleate e tedesche nella Sicilia del 1943–1944, Giovanni Bartolone, p.44, 2005

Bibliography

- Alexander, Harold (12 February 1948). The Conquest of Sicily from 10 July 1943 to 17 August 1943. Alexander's Despatches. published in The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 38205. pp. 1009–1025. 10 February 1948.

- Atkinson, Rick (2007). Volume II: The Day of Battle, The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943–1944. The Liberation Trilogy. New York: Henry Holt. pp. 816 pages. ISBN 978-0-8050-6289-2.

- Bimberg, Edward L. (1999). The Moroccan Goums. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0-313-30913-2.

- Birtle, Andrew J. (1993). Sicily 1943. The U.S. Army WWII Campaigns. Washington: United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 0-16-042081-4. CMH Pub 72-16.

- Brown, Shaun R.G. (1984). The Loyal Edmonton Regiment at war, 1943–1945 (M.A. thesis). Wilfrid Laurier University.

- Carver, Field Marshal Lord (2001). The Imperial War Museum Book of the War in Italy 1943–1945. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-330-48230-0.

- Copp, Terry; McGreer, Eric; Symes, Matt (2008). The Canadian Battlefields in Italy: Sicily and Southern Italy. Waterloo: Laurier Centre for Military, Strategic and Disarmament Studies.

- Costanzo, Ezio (2003). Sicilia 1943: breve storia dello sbarco alleato (in Italian). Catania, Italy: Le Nove Muse. ISBN 88-87820-21-X.

- D'Este, Carlo (2008). Bitter Victory: The Battle for Sicily 1943. London: Arum Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84513-329-0.

- Dickson, Keith (2001). World War II for Dummies. New York City.

- Ferguson, Gregor; Lyles, Kevin (1984). The Paras 1940–1984: British airborne forces 1940–1984. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 0-85045-573-1.

- Follain, John (2005). Mussolini's Island: The Invasion of Sicily Through The Eyes Of Those Who Witnessed The Campaign. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Grigg, John (1982). 1943: The Victory that Never Was. Kensington Pub Corp. ISBN 0-8217-1596-8.

- Holland, James (2004) Fortress Malta: An Island Under Siege, 1940–1943. (London: Phoenix). ISBN 9780304366545.

- Hoyt, Edwin P. (2007) [2002]. Backwater War: The Allied Campaign in Italy, 1943–45. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3382-3.

- Jowett, Philip S.; Andrew, Stephen (2001). The Italian Army 1940–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-866-6.

- Mitcham, Samuel W. & von Stauffenberg, Friedrich (2007) [1991]. The Battle of Sicily: How the Allies Lost Their Chance for Total Victory. Mechanicsberg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3403-X.

- Molony, Brigadier C.J.C.; with Flynn, Captain F.C. (R.N.); Davies, Major-General H.L. & Gleave, Group Captain T.P. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO:1973]. Butler, Sir James, ed. The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume V: The Campaign in Sicily 1943 and The Campaign in Italy 3 September 1943 to 31 March 1944. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-069-6.

- Tomblin, Barbara (2004). With Utmost Spirit: Allied Naval Operations in the Mediterranean, 1942–1945. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2338-0.

- Shaw, A (2002) [2000]. World War II: Day by Day. Hoo: Grange. ISBN 1-84013-363-5.

- Zuehlke, Mark (2010). Operation husky: the Canadian invasion of Sicily, July 10 – August 7, 1943. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 1-55365-539-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Husky. |

- Describes Operation Mincemeat

- Italian 3rd Battalion, 34th Regiment, "Livorno" Infantry Division in the Gela Beachhead Counterattack

- Husky Operations Plan Sicily

- Excerpt from The Day Of Battle by Rick Atkinson

- March From The Beaches, Time, 26 July 1943

- Canadians in Sicily, 1943 Canadians in Sicily: Photos, battle info, video footage and newspaper archives.

- Birtle, Andrew J. Sicily 1943. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-26.

- World War Two Online Newspaper Archives – The Sicilian and Italian Campaigns, 1943–1945

- Operation Husky: The Allied Invasion of Sicily, 1943 by Thomas E. Nutter

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and Second World War (Sicily)

- 2nd World War Best of Sicily History of the Allied Campaign and its social context

- The 82nd Airborne during World War II

- Historical Museum of the Military Invasion of Sicily, 1943 (Museo Storico dello Sbarco in Sicilia 1943) Dedicated to the historical event which culminated in the liberation of Sicily and Italy from the German occupation.

- German Soldiers' Cemetery, Motta S. Anastasia, Sicily (in German)

- Commonwealth War Cemetery, Catania, Sicily

- Syracuse War Cemetery, Sicily

- Agira Canadian War Cemetery, Sicily

- Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial

- COHQ bulletin Y6 digest of reports on Operation 'Husky'

- COHQ bulletin Y1 notes on the planning and assault phase of the Sicilian operation

- 45th Infantry Division in the Sicilian Campaign

- The Irish Brigade 1941–47 Contains an account of the 38th (Irish) Brigade in Sicily in August 1943.

- Licata Landing La Vedettaonline