Allicin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Propene-1-sulfinothioic acid S-2-propenyl ester | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

3-[(Prop-2-ene-1-sulfinyl)sulfanyl]prop-1-ene | |

| Identifiers | |

| 1752823 | |

| 539-86-6 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:28411 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL359965 |

| ChemSpider | 58548 |

| EC number | 208-727-7 |

| |

| IUPHAR ligand | 2419 |

| Jmol-3D images | Image Image |

| KEGG | C07600 |

| MeSH | Allicin |

| PubChem | 65036 |

| |

| UNII | 3C39BY17Y6 |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula |

C6H10OS2 |

| Molar mass | 162.27 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colourless liquid |

| Density | 1.112 g cm−3 |

| Melting point | <25 °C |

| Boiling point | decomposes |

| Except where noted otherwise, data is given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Allicin is an organosulfur compound obtained from garlic, a species in the family Alliaceae.[1] It was first isolated and studied in the laboratory by Chester J. Cavallito and John Hays Bailey in 1944.[2][3] When fresh garlic is chopped or crushed, the enzyme alliinase converts alliin into allicin, which is responsible for the aroma of fresh garlic.[4] The allicin generated is very unstable and quickly changes into a series of other sulfur containing compounds such as diallyl disulfide.[5] It exhibits antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and antiprotozoal activity.[6] Allicin is garlic's defense mechanism against attacks by pests.[7]

Structure and occurrence

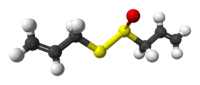

Allicin features the thiosulfinate functional group, R-S(O)-S-R. The compound is not present in garlic unless tissue damage occurs,[1] and is formed by the action of the enzyme alliinase on alliin.[1] Allicin is chiral but occurs naturally only as a racemate.[3] The racemic form can also be generated by oxidation of diallyl disulfide:[8]

- (SCH2CH=CH2)2 + RCO3H → CH2=CHCH2S(O)SCH2CH=CH2 + RCO2H

Alliinase is irreversibly deactivated below pH 3; as such, allicin is generally not produced in the body from the consumption of fresh or powdered garlic.[9][10] Furthermore, allicin can be unstable, breaking down within 16 h at 23 °C.[11]

Biosynthesis of Allicin

Allicin is an oily, slightly yellow liquid that gives garlic its unique odor. It is a thioester of sulfenic acid and is also known as allyl thiosulfinate.[12] Its biological activity can be attributed to both its antioxidant activity and its reaction with thiol containing proteins.[13]

In the biosynthesis of allicin (thio-2-propene-1-sulfinic acid S-allyl ester), cysteine is first converted into alliin (+ S-allyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide). The enzyme alliinase, which contains pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), cleaves alliin, generating allysulfenic acid, pyruvate, and ammonium.[13] At room temperature allysulfenic acid is unstable and highly reactive, which cause two molecules of it to spontaneously combine in a dehydration reaction to form allicin.[12]

Allicin is produced in garlic cells when they are damaged, which is why garlic’s scent is most potent once it is being cut or cooked. It is believed that alliin and alliinase are kept in separate compartments of the cells and can only combine once these compartments have been ruptured.[14]

Potential health benefits

Several animal studies published between 1995 and 2005 indicate that allicin may reduce atherosclerosis and fat deposition,[15][16] normalize the lipoprotein balance, decrease blood pressure,[17][18] have anti-thrombotic[19] and anti-inflammatory activities, and function as an antioxidant to some extent.[20][21][22] Other animal studies have shown a strong oxidative effect in the gut that can damage intestinal cells, though many of these results were obtained by excessive amounts of allicin, which has been clearly shown to have some toxicity at high amounts, or by physically injecting the lumen itself with allicin, which may not be indicative of what would happen via oral ingestion of allicin or garlic supplements.[23][24] A randomized clinical trial funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States and published in the Archives of Internal Medicine in 2007 found that the consumption of garlic in any form did not reduce blood cholesterol levels in patients with moderately high baseline cholesterol levels.[25] The fresh garlic used in this study contained substantial levels of allicin, so the study casts doubt on the ability of allicin when taken orally to reduce blood cholesterol levels in human subjects.

In 2009, Vaidya, Ingold and Pratt clarified the mechanism of the antioxidant activity of garlic, such as trapping damaging free radicals. When allicin decomposes, it forms 2-propenesulfenic acid, and this compound is what binds to the free-radicals.[26] The 2-propenesulfenic formed when garlic is cut or crushed has a half-life of less than one second.[27]

Antibacterial activity

Allicin has been found to have numerous antimicrobial properties, and has been studied in relation to both its effects and its biochemical interactions.[28] One potential application is in the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), an increasingly prevalent concern in hospitals. A screening of allicin against 30 strains of MRSA found high level of antimicrobial activity, including against strains that are resistant to other chemical agents.[29] Of the strains tested, 88% had minimum inhibitory concentrations for allicin liquids of 16 mg/L, and all strains were inhibited at 32 mg/L. Furthermore, 88% of clinical isolates had minimum bactericidal concentrations of 128 mg/L, and all were killed at 256 mg/L. Of these strains, 82% showed intermediate or full resistance to mupirocin. This same study examined use of an aqueous cream of allicin, and found it somewhat less effective than allicin liquid. At 500 mg/L, however, the cream was still active against all the organisms tested—which compares well with the 20 g/L mupirocin currently used for topical application.[29]

A water-based formulation of purified allicin was found to be more chemically stable than other preparations of garlic extracts.[29] They proposed that the stability may be due to the hydrogen bonding of water to the reactive oxygen atom in allicin and also to the absence of other components in crushed garlic that destabilize the molecule.[30]

Antiviral activity

Allicin has antiviral activity both in vitro and in vivo. Among the viruses susceptible to allicin are Herpes simplex type 1 and 2, Parainfluenza virus type 3, human Cytomegalovirus, Influenza B, Vaccinia virus, Vesicular stomatitis virus and Human rhinovirus type 2.[31]

A small[32] (146 healthy adults) double-blind, placebo-controlled study found that a daily supplement containing purified allicin, had dramatic results[33] by reducing the risk of catching a cold by 64%, the symptom duration was reduced by 70% and those in the treatment group were much less likely to develop more than one cold.[34][35]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to allicin. |

- Allyl isothiocyanate, the active piquant chemical in mustard, radishes, horseradish and wasabi

- Capsaicin, the active piquant chemical in chili peppers

- Piperine, the active piquant chemical in black pepper

- syn-Propanethial-S-oxide, the chemical found in onions

- List of phytochemicals in food

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Eric Block (1985). "The chemistry of garlic and onions". Scientific American 252 (March): 114–9. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0385-114. PMID 3975593.

- ↑ Cavallito, Chester J.; Bailey, John Hays (1944). "Allicin, the Antibacterial Principle of Allium sativum. I. Isolation, Physical Properties and Antibacterial Action". Journal of the American Chemical Society 66 (11): 1950. doi:10.1021/ja01239a048.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Eric Block (2010). Garlic and Other Alliums: The Lore and the Science. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry.

- ↑ Kourounakis, PN; Rekka, EA (November 1991). "Effect on active oxygen species of alliin and Allium sativum (garlic) powder". Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 74 (2): 249–252. PMID 1667340.

- ↑ "Allicin and related compounds: Biosynthesis, synthesis and pharmacological activity" (PDF). Facta universitatis 9 (1): 9–20. 2011. doi:10.2298/FUPCT1101009I.

- ↑ Salama, A. A.; Aboulaila, M; Terkawi, M. A.; Mousa, A; El-Sify, A; Allaam, M; Zaghawa, A; Yokoyama, N; Igarashi, I (2014). "Inhibitory effect of allicin on the growth of Babesia and Theileria equi parasites". Parasitology Research 113 (1): 275–83. doi:10.1007/s00436-013-3654-2. PMID 24173810.

- ↑ What is Allicin?. Phytochemicals.info. Retrieved on 2012-12-26.

- ↑ Cremlyn, R. J. W. (1996). An introduction to organosulfur chemistry. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-95512-4.

- ↑ Brodnitz, M.H., Pascale, J.V., Derslice, L.V. (1971). "Flavor components of garlic extract". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 19 (2): 273–5. doi:10.1021/jf60174a007.

- ↑ Yu, Tung-HSI; Wu, Chung-MAY (1989). "Stability of Allicin in Garlic Juice". Journal of Food Science 54 (4): 977. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1989.tb07926.x.

- ↑ Hahn, G (1996). Koch, HP; Lawson, LD, eds. Garlic: the science and therapeutic application of Allium sativum L and related species (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins. pp. 1–24. ISBN 0-683-18147-5.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Mechanism and kinetics of synthesis of allicin.". Pharmazie 59 (1): 10–4. Jan 2004. PMID 14964414.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "The mode of action of allicin: trapping of radicals and interaction with thiol containing proteins.". Biochim Biophys Acta 1379 (2): 233–44. Feb 1998. doi:10.1016/s0304-4165(97)00104-9. PMID 9528659.

- ↑ "Allicin, a naturally occurring antibiotic from garlic, specifically inhibits acetyl-CoA synthetase.". FEBS Lett 261 (1): 106–8. Feb 1990. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(90)80647-2. PMID 1968399.

- ↑ S. Eilat, Y. Oestraicher, A. Rabinkov, D. Ohad, D. Mirelman, A. Battler, M. Eldar and Z. Vered (1995). "Alteration of lipid profile in hyperlipidemic rabbits by allicin, an active constituent of garlic". Coron. Artery Dis. 6 (12): 985–990. PMID 8723021.

- ↑ D. Abramovitz, S. Gavri, D. Harats, H. Levkovitz, D. Mirelman, T. Miron, S. Eilat-Adar, A. Rabinkov, M. Wilchek, M. Eldar and Z. Vered, (1999). "Allicin-induced decrease in formation of fatty streaks (atherosclerosis) in mice fed a cholesterol-rich diet". Coron. Artery Dis. 10 (7): 515–9. doi:10.1097/00019501-199910000-00012. PMID 10562920.

- ↑ Silagy CA, Neil HA (1994). "A meta-analysis of the effect of garlic on blood pressure". J Hypertens 12 (4): 463–8. doi:10.1097/00004872-199404000-00017. PMID 8064171.

- ↑ A. Elkayam, D. Mirelman, E. Peleg, M. Wilchek, T. Miron, A. Rabinkov, M. Oron-Herman and T. Rosenthal (2003). "The effects of allicin on weight in fructose-induced hyperinsulinemic, hyperlipidemic, hypertensive rats". Am. J. Hypertens 16 (12): 1053–6. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.07.011. PMID 14643581.

- ↑ Srivastava KC (1986). "Evidence for the mechanism by which garlic inhibits platelet aggregation". Prostaglandins Leukot Med 22 (3): 313–321. doi:10.1016/0262-1746(86)90142-3. PMID 3088604.

- ↑ U. Sela, S. Ganor, I. Hecht, A. Brill, T. Miron, A. Rabinkov, M. Wilchek, D. Mirelman, O. Lider and R. Hershkoviz (2004). "Allicin inhibits SDF-1alpha-induced T cell interactions with fibronectin and endothelial cells by down-regulating cytoskeleton rearrangement, Pyk-2 phosphorylation and VLA-4 expression". Immunology 111 (4): 391–399. doi:10.1111/j.0019-2805.2004.01841.x. PMC 1782446. PMID 15056375.

- ↑ Lindsey J. Macpherson, Bernhard H. Geierstanger, Veena Viswanath, Michael Bandell, Samer R. Eid, SunWook Hwang, and Ardem Patapoutian (2005). "The pungency of garlic: Activation of TRPA1 and TRPV1 in response to allicin]". Current Biology 15 (10): 929–934. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.018. PMID 15916949.

- ↑ Bautista DM, Movahed P, Hinman A, Axelsson HE, Sterner O, Hogestatt ED, Julius D, Jordt SE and Zygmunt PM (2005). "Pungent products from garlic activate the sensory ion channel TRPA1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (34): 12248–52. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505356102. PMC 1189336. PMID 16103371.

- ↑ Banerjee, SK; Mukherjee, PK; Maulik, SK (2001). "Garlic as an Antioxidant: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly". Phytotherapy Research 17 (2): 97–106. doi:10.1002/ptr.1281. PMID 12601669.

- ↑ Amagase, H; Petesch, BL; Matsuura, H; Kasuga, S; Itakura, Y (2003). "Intake of garlic and its bioactive components". J Nutr 131 (3s): 955S–62S. PMID 11238796.

- ↑ Gardner CD, Lawson LD, Block E et al. (2007). "Effect of raw garlic vs commercial garlic supplements on plasma lipid concentrations in adults with moderate hypercholesterolemia: a randomized clinical trial". Arch. Intern. Med. 167 (4): 346–53. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.4.346. PMID 17325296.

- ↑ Vaidya, Vipraja; Keith U. Ingold; Derek A. Pratt (2009). "Garlic: Source of the Ultimate Antioxidants – Sulfenic Acids". Angewandte Chemie 121 (1): 163–6. doi:10.1002/ange.200804560. PMID 19040240.

- ↑ Block E, Dane AJ, Thomas S, Cody RB (2010). "Applications of Direct Analysis in Real Time–Mass Spectrometry (DART-MS) in Allium Chemistry. 2-Propenesulfenic and 2-Propenesulfinic Acids, Diallyl Trisulfane S-Oxide and Other Reactive Sulfur Compounds from Crushed Garlic and Other Alliums". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 58 (8): 4617–25. doi:10.1021/jf1000106. PMID 20225897.

- ↑ Ankri, S; Mirelman D (1999). "Antimicrobial properties of allicin from garlic". Microbes Infect 2 (2): 125–9. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(99)80003-3. PMID 10594976.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Cutler, RR; P Wilson (2004). "Antibacterial activity of a new, stable, aqueous extract of allicin against methicillan-resistant Staphylococcus aureus" (PDF). British Journal of Biomedical Science 61 (2): 71–4. PMID 15250668.

- ↑ Lawson, LD; Koch HP, ed. (1996). The composition and chemistry of garlic cloves and processed garlic; in Garlic: the science and therapeutic application of Allium sativum L and related species (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins. pp. 37–107. ISBN 0-683-18147-5.

- ↑ Ilić, Dušica; Nikolić, Vesna; Ćirić, Ana; Soković, Marina; Stanojković, Tatjana; Kundaković, Tatjana; Stanković, Mihajlo; Nikolić, Ljubiša (9 January 2012). "Cytotoxicity and antimicrobial activity of allicin and its transformation products". Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 6 (1): 59–65. doi:10.5897/JMPR11.917.

- ↑ Nahas, R.; Balla, A. (2011). "Complementary and alternative medicine for prevention and treatment of the common cold". Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien 57 (1): 31–36. PMC 3024156. PMID 21322286.

- ↑ Complementary and alternative medicine for prevention and treatment of the common cold. Cfp.ca. Retrieved on 2012-12-26.

- ↑ HEALTH | Garlic 'prevents common cold'. BBC News (2001-10-03). Retrieved on 2012-12-26.

- ↑ Josling, P. (2001). "Preventing the common cold with a garlic supplement: A double-blind, placebo-controlled survey". Advances in therapy 18 (4): 189–193. doi:10.1007/bf02850113. PMID 11697022.

External links

- Johnston, Nicole (2002). "News in Brief: Garlic: A natural antibiotic". Mdd modern drug discovery 5 (4).

Allicin, the major component of garlic, is one such agent, and it was recently shown to be potent against VRE and MRSA in two studies presented at the 41st Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy in Chicago in December.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||