Allah jang Palsoe

| Allah jang Palsoe | |

|---|---|

| Written by | Kwee Tek Hoay |

| Characters |

|

| Date premiered | 1919 |

| Original language | Vernacular Malay |

Allah jang Palsoe ([aˈlah ˈjaŋ palˈsu]; Perfected Spelling: Allah yang Palsu; Indonesian for The False God) is a 1919 stage drama in six acts by ethnic-Chinese writer Kwee Tek Hoay. The Malay-language play follows two brothers, one a devout son who holds firmly to his morals and personal honour, the other who worships money and prioritises personal gain. Over more than a decade, the two ultimately learn that money (the titular false god) is not the path to happiness. Other readings of the play have shown a Chinese nationalist identity and depiction of negative traits in women.

Kwee's first stage play, Allah jang Palsoe was written as a realist response to the whimsical bangsawan and stamboel theatres. Its inaugural performance was a commercial success, though the published stageplay was a loss. By 1930 the play, though deemed a difficult one, was performed by various ethnic Chinese troupes to popular acclaim; it also inspired two of Kwee's later works: the stage play Korbannja Kong-Ek (1926) and the novel Boenga Roos dari Tjikembang (1927). In 2006 the script was republished with updated spelling by the Lontar Foundation.

Plot

Brothers Tan Kioe Lie and Tan Kioe Gie are preparing to leave their home in Cicuruk and find work in the city: Lie is to go to Bandung and find work at a company there, while Gie is to go to Batavia (now Jakarta) and become a letter-setter. As they are packing, Kioe Lie's fiancée Gouw Hap Nio comes by. She leaves some snacks with their father, the poor farmer Tan Lauw Pe, before going home, promising to take care of Pe while his sons are away. Lie and Gie finish packing, say goodbye to their father, and head for the train station.

Three years later, Lie visits Gie in the latter's Batavia home. Gie has become the deputy editor in chief of the newspaper Kamadjoean and is known throughout the city as a generous philanthropist. Lie, meanwhile, has risen to manager of a tapioca factory, but is planning to leave his boss Lie Tjin Tjaij for his competitor, Tjio Tam Bing, who has offered Lie more than twice as much money. Gie asks Lie to reconsider, or at the very least not take all of Tjaij's customers with him, but the latter is set on his goals, saying that God helps those who help themselves. Before Lie leaves for lunch with Bing, the brothers discuss marriage: as Lie has no intent of marrying Hap Nio soon, Gie asks permission to marry first; though Lie disapproves of Gie's sweetheart, a poor orphan girl named Oeij Ijan Nio, he gives his permission.

Another four years pass, and Gie has become editor in chief of Kemadjoean and married Ijan Nio. He is concerned, however, over its owner's new political orientation: rather than the previous pro-China stance, the owner, Oeij Tjoan Siat, is aiming to make the paper pro-Dutch East Indies, a stance that Gie considers a betrayal to ethnic Chinese. When Siat comes to Gie's home to ask him to follow the former's new political leanings, heavily influenced by a monthly bursary of 2,000 gulden offered by an unnamed political party, Gie refuses: he instead resigns from the newspaper.

During the following week the family sell their belongings and prepare to move back to Cicuruk. This departure is delayed by a visit from Lie, who reveals that he will be marrying Bing's widow Tan Houw Nio –Bing having died the year before. Gie is horrified, both because the widow has the same surname[lower-alpha 1] and because two years previously Lie had promised their father on the latter's deathbed to marry Hap Nio. After an extensive argument, Lie leaves the home, saying he no longer considers Gie to be his brother.

Five years later, Lie and Houw Nio's marriage is failing. Owing to poor investments (some made with embezzled money), exacerbated by Houw Nio's gambling and Lie's keeping of a mistress, they have lost their vast fortune. Lie tries to convince Houw Nio to sell her jewellery, allowing him to pay back the money he had stolen. Houw Nio, however, refuses, telling him to just sell the house and jewellery he had bought his mistress before leaving for her family's home. Soon afterwards, Lie's friend Tan Tiang An comes to tell him that he is liable to be arrested by the police if he does not leave the country. Together they rent a car and Lie heads for the port at Batavia.

On his way through Cicuruk, Lie's car breaks down and, while the driver attempts to fix it, Lie takes shelter in a nearby home, only to learn from the manservant that it belongs to Gie. Gie and Lauw Nio, having worked hard, have built up a vast farm, garden, and orchard that provides them with more than enough income to live comfortably; the two, who continue to be philanthropists, are friends with high ranking people in the area. Furthermore, Hap Nio is happily married to a rich orchard administrator. When Gie and his companions return from playing tennis they discover Lie hiding under a piano, ashamed to be seen. Lie admits he was wrong to be greedy and, when a police officer comes to arrest him, confesses to poisoning Bing, then runs outside and shoots himself.

Writing

Allah jang Palsoe was written by journalist Kwee Tek Hoay. Born to an ethnic Chinese textile merchant and his native wife,[1] raised in Chinese culture and schools that focused on modernity, by the time he wrote the novel, Kwee Tek Hoay was an active proponent of Buddhist theology. However, he also wrote extensively on themes relating to native Indonesians[2] and was a keen social observer.[3] He read extensively in Dutch, English, and Malay, and drew on these readings after becoming a writer.[4]

The work was Kwee Tek Hoay's first stage play,[5] and, according to historian Nio Joe Lan, the first stage drama in Malay by a Chinese writer.[6] The plot was based on E. Phillips Oppenheim's short story "The False Gods".[7] The six-act work was written in vernacular Malay, the lingua franca of the Dutch East Indies. Sumardjo praises Kwee Tek Hoay's use of the language, writing that it flowed well.[8]

At the time Allah jang Palsoe was written, stage performances were very much influenced by orality. Contemporary theatres, such as bangsawan and stamboel, were unscripted and, generally, used unrealistic settings and plotlines.[9] Kwee Tek Hoay heavily disapproved of such a technique, considering it ""better to say things as they are, than to create events out of nothing, which although perhaps more entertaining and satisfying to viewers or readers, are falsehoods and lies, going against the truth."[lower-alpha 2][10] After condemning contemporary playwrights who merely wrote down existing stories, Kwee Tek Hoay expressed the hope that ultimately a unique form of Chinese Malay theatre could be developed.[11]

In a preface to his 1926 drama Korbannja Kong-Ek (The Victim of Kong-Ek), Kwee Tek Hoay wrote that he had drawn inspiration from realist Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, having read and reread the author's works. Indonesian literary critic Sapardi Djoko Damono finds signs of Ibsen's influence already present in Allah jang Palsoe. He compares the stage directions in Hedda Gabler and Allah jang Palsoe, finding both of them to give similarly detailed instructions.[10]

Themes

The title of the play is a reference to money,[12] with an underlying didactic message that money is not everything in the world, and that an unquenchable thirst for it would turn one into "a money animal".[13] Throughout the dialogue, money is referred to as the false God, with Lie as a character who deifies money to the point of ignoring his other duties and only realising his error after it is too late. Gie, although he does become rich, does not consider money as a god, but instead becomes a philanthropist and holds to his morals. Damono writes that such an issue would have been common among ethnic Chinese in the contemporary Indies, and as such would have made the play a favourite of social organisations.[14]

Indonesian literary critic Jakob Sumardjo likewise notes money as the central issue of Allah jang Palsoe, writing that the play shows individuals doing anything, even sacrificing their values, to earn it. He writes that such conditions are common even in the best of times,[13] and considers Kwee Tek Hoay's message to have been too heavily based in morality rather than considerations of social and human factors. As a result, he writes that readers are brought to understand the lust for money as a "human illness" ("penyakit kemanusiaan") which must be overcome: do as Tan Kioe Gie, not as Tan Kioe Lie.[15] John Kwee of the University of Auckland, citing Gie's departure from Kamadjoean, suggests that this was a challenge directed at the Chinese Malay press, then becoming increasingly commercial.[11]

Other readings have been more diverse. Sinologist Thomas Rieger notes issues of a Chinese national identity, pointing to Gie as a young man "excelling in all Confucianist values", leaving his comfortable job rather than promote an apologetic attitude towards the Dutch colonial government to the detriment of his ethnic Chinese peers.[16] Another sinologist, Myra Sidharta, looks at Kwee Tek Hoay 's view of women. She writes that his depiction of an ideal woman was not yet fully developed in Allah jang Palsoe, though she finds Houw Nio to be a depiction of how a woman should not act: selfish and addicted to gambling.[17]

Release and reception

Although initially criticised for lack of interesting costumes, instead emphasising everyday clothing, the play was well received.[18] Kwee Tek Hoay notes that one performance, intended to raise money for the Tiong Hoa Hak Tong, garnered 10,000 gulden. Such fundraising performances were common in the 1910s Indies, particularly among the ethnic Chinese community.[18] After the performance, Kwee Tek Hoay received numerous letters from fans, spurring him to continue writing.[19] Other troupes were allowed to perform the play, though any proceeds were to go to the Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan branch in Bogor.[20]

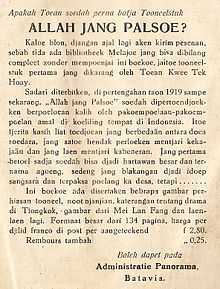

The script was released as a book by Batavia-based publisher Tjiong Koen Bie in mid-1919.[21] Kwee Tek Hoay paid for this printing, a run of 1,000 copies, out of his own pocket and saw large financial losses.[7] The stage play was republished in 2006, using the Perfected Spelling System, as part of the first volume of the Lontar Foundation's anthology of Indonesian stage dramas.[22] In 1926 Kwee Tek Hoay wrote that, after Allah jang Palsoe, the quality of stage performances in the Indies had increased noticeably.[23] Sumardjo writes that, though Allah jang Palsoe was published seven years before the Rustam Effendi's Bebasari (generally considered the first canonic Indonesian stage drama), Kwee Tek Hoay's writing shows all the hallmarks of a literary work.[24]

Though, according to an advertisement, by 1930 Allah jang Palsoe had been performed "tens" ("poeloehan") of times[5] and was popular with ethnic Chinese theatre troupes,[7] it was considered quite difficult to perform. Kwee Tek Hoay considered it too difficult for native troupes and, when one such troupe, the Union Dalia Opera, requested permission to perform it, he instead wrote a new story for them. This later became Kwee Tek Hoay's best-selling novel Boenga Roos dari Tjikembang (The Rose of Cikembang).[25] Another of Kwee Tek Hoay's works, Korbannja Kong-Ek, was inspired by a viewer, who wrote him a letter asking for a comforting and morally didactic play.[26]

Notes

- ↑ In Chinese tradition, such a relationship would be considered incest (Sidharta 1989, p. 59).

- ↑ Original: "... lebih baek tuturkan kaadaan yang sabetulnya, dari pada ciptaken yang ada dalem angen-angen, yang meskipun ada lebih menyenangken dan mempuasken pada pembaca atau penonton, tapi palsu dan justa, bertentangan dengan kaadaan yang benar."

References

- ↑ Sutedja-Liem 2007, p. 273.

- ↑ JCG, Kwee Tek Hoay.

- ↑ The Jakarta Post 2000, Chinese-Indonesian writers.

- ↑ Sidharta 1996, pp. 333–334.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kwee 1930, p. 99.

- ↑ Nio 1962, p. 151.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Sumardjo 2004, p. 140.

- ↑ Sumardjo 2004, p. 142.

- ↑ Damono 2006, p. xxii.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Damono 2006, pp. xvii, xvix.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kwee 1989, p. 167.

- ↑ Damono 2006, p. xxi.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Sumardjo 2004, p. 143.

- ↑ Damono 2006, pp. xxi–xxii.

- ↑ Sumardjo 2004, pp. 143–144.

- ↑ Rieger 1996, p. 161.

- ↑ Sidharta 1989, p. 59.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Damono 2006, p. xviii.

- ↑ Kwee 2002, p. 2.

- ↑ Kwee 1980, p. 89.

- ↑ Kwee 1930, p. 99; Lontar Foundation 2006, p. 95

- ↑ Lontar Foundation 2006, p. 95.

- ↑ Kwee 2002, p. 9.

- ↑ Sumardjo 2004, p. 144.

- ↑ Kwee 2001, pp. 298–299.

- ↑ Kwee 2002, p. 4.

Works cited

- "Chinese-Indonesian writers told tales of life around them". The Jakarta Post. 26 May 2000. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Damono, Sapardi Djoko (2006). "Sebermula Adalah Realisme" [In the Beginning there was Realism]. In Lontar Foundation. Antologi Drama Indonesia 1895–1930 [Anthology of Indonesian Dramas 1895–1930] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Lontar Foundation. pp. xvii–xxix. ISBN 978-979-99858-2-8.

- Lontar Foundation, ed. (2006). Antologi Drama Indonesia 1895–1930 [Anthology of Indonesian Dramas 1895–1930] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Lontar Foundation. ISBN 978-979-99858-2-8.

- Kwee, John (1980). "Kwee Tek Hoay: A Productive Chinese Writer of Java (1880–1952)". Archipel 19 (19): 81–92. doi:10.3406/arch.1980.1526.

- Kwee, John (1989). "Kwee Tek Hoay, Sang Dramawan" [Kwee Tek Hoay, the Dramatist]. In Sidharta, Myra. 100 Tahun Kwee Tek Hoay: Dari Penjaja Tekstil sampai ke Pendekar Pena [100 Years of Kwee Tek Hoay: From Textile Peddler to Pen-Wielding Warrior] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Sinar Harapan. pp. 166–179. ISBN 978-979-416-040-4.

- "Kwee Tek Hoay". Encyclopedia of Jakarta (in Indonesian). Jakarta City Government. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- Kwee, Tek Hoay (1930). Boenga Roos dari Tjikembang [The Rose of Tjikembang] (in Malay). Batavia: Panorama.

- Kwee, Tek Hoay (2001). "Bunga Roos dari Cikembang". In A.S., Marcus; Benedanto, Pax. Kesastraan Melayu Tionghoa dan Kebangsaan Indonesia [Chinese Malay Literature and the Indonesian Nation] (in Indonesian) 2. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. pp. 297–425. ISBN 978-979-9023-45-2.

- Kwee, Tek Hoay (2002). "Korbannya Kong-Ek". In A.S., Marcus; Benedanto, Pax. Kesastraan Melayu Tionghoa dan Kebangsaan Indonesia [Chinese Malay Literature and the Indonesian Nation] (in Indonesian) 6. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. pp. 1–108. ISBN 978-979-9023-82-7.

- Nio, Joe Lan (1962). Sastera Indonesia-Tionghoa [Indonesian-Chinese Literature] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Gunung Agung. OCLC 3094508.

- Rieger, Thomas (1996). "From Huaqiao to Minzu: Constructing New Identities in Indonesia's Peranakan-Chinese Literature". In Littrup, Lisbeth. Identity in Asian Literature. Surrey: Curzon Press. pp. 151–172. ISBN 978-0-7007-0367-8.

- Sidharta, Myra (1989). "Bunga-Bunga di Taman Mustika: Pandangan Kwee Tek Hoay Terhadap Wanita dan Soal-soal Kewanitaan" [Flowers in the Bejeweled Garden: Kwee Tek Hoay's Views on Women and Related Issues]. In Sidharta, Myra. 100 Tahun Kwee Tek Hoay: Dari Penjaja Tekstil sampai ke Pendekar Pena [100 Years of Kwee Tek Hoay: From Textile Peddler to Pen-Wielding Warrior] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Sinar Harapan. pp. 55–82. ISBN 978-979-416-040-4.

- Sidharta, Myra (1996). "Kwee Tek Hoay, Pengarang Serbabisa" [Kwee Tek Hoay, All-round Author]. In Suryadinata, Leo. Sastra Peranakan Tionghoa Indonesia [Indonesian Peranakan Chinese Literature] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Grasindo. pp. 323–348.

- Sumardjo, Jakob (2004). Kesusastraan Melayu Rendah [Low Malay Literature] (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Galang Press. ISBN 978-979-3627-16-8.

- Sutedja-Liem, Maya (2007). "De Roos uit Tjikembang". De Njai: Moeder van Alle Volken: 'De Roos uit Tjikembang' en Andere Verhalen [The Njai: Mother of All Peoples: 'De Roos uit Tjikembang' and Other Stories] (in Dutch). Leiden: KITLV. pp. 269–342.