Alice Neel

| Alice Neel | |

|---|---|

| Born |

January 28, 1900 Merion Square, Pennsylvania |

| Died |

October 13, 1984 (aged 84) New York, NY |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

Alice Neel (January 28, 1900 – October 13, 1984) was an American visual artist, who was particularly well known for oil painting and for her portraits depicting friends, family, lovers, poets, artists and strangers. Her paintings are notable for their expressionistic use of line and color, psychological acumen, and emotional intensity. Neel was called "one of the greatest portrait artists of the 20th century" by Barry Walker, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, which organized a retrospective of her work in 2010.[1]

Life and work

Early life

Alice Neel was born on January 28, 1900[2][3] in Merion Square, Pennsylvania to George Washington Neel, an accountant for the Pennsylvania Railroad, and Alice Concross Hartley Neel.[4] In mid-1900, her family moved to the rural town of Colwyn, Pennsylvania.[4] She was the third of four children.[5] She was raised into a straight-laced middle-class family during a time when there were limited expectations and opportunities for women.[2][5] Her mother had said to her, "I don't know what you expect to do in the world, you're only a girl.[5]

In 1918, after graduating High School, she took the Civil Service exam and got a high-paying clerical position in order to help support her parents.[6] After three years of work, taking art classes by night in Philadelphia, Neel enrolled in the Fine Art program at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (now Moore College of Art) in 1921.[7] She graduated in 1925.[2][5] Neel often said that she chose to attend an all-girls school so as not to be distracted from her art by the temptations of the opposite sex.

Cuba

She met an upper-class Cuban painter in 1924 named Carlos Enríquez at the Chester Springs summer school run by PAFA.[3] They were wed on 1 June 1925 in Colwyn, Pennsylvania.[7] After marrying Neel eventually moved to Havana[2][5] to live with Enríquez’s family. In Havana, Neel was embraced by the burgeoning Cuban avant-garde, a set of young writers, artists and musicians. In this environment Neel developed the foundations of her lifelong political consciousness and commitment to equality. During this time, she had 7 servants and lived in a mansion.[2]

Personal difficulties, themes for art

Neel's daughter, Santillana, was born on 26 December 1926 in Havana.[7] In 1927, though, the couple returned to the United States to live in New York.[2] Just a month before Santillana’s first birthday, she died of diphtheria.[2] The trauma caused by Santillana’s death infused the content of Neel’s paintings, setting a precedent for the themes of motherhood, loss, and anxiety that permeated her work for the duration of her career. Shortly following Santillana’s death, Neel became pregnant with her second child.[7] On 24 November 1928, Isabella Lillian (called Isabetta) was born in New York City.[7] Isabetta’s birth was the inspiration for Neel's "Well Baby Clinic", a bleak portrait of mothers and babies in a maternity clinic more reminiscent of an insane asylum than a nursery.

In the spring of 1930, Carlos had given the impression that he was going overseas to look for a place to live in Paris. Instead, he returned to Cuba, taking Isabetta with him. Mourning the loss of her husband and daughter, Neel suffered a massive nervous breakdown, was hospitalized, and attempted suicide.[2] She was placed in the suicide ward of the Philadelphia General Hospital.

Even in the insane asylum, she painted. Alice loved a wretch. She loved the wretch in the hero and the hero in the wretch. She saw that in all of us, I think.— Ginny Neel, Alice's daughter-in-law[2]

Deemed stable almost a year later, Neel was released from the sanatorium in 1931 and returned to her parents’ home. Following an extended visit with her close friend and frequent subject, Nadya Olyanova, Neel returned to New York.

Depression era

There Neel painted the local characters, including Joe Gould, whom she famously depicted in 1933 with multiple penises, which represented his inflated ego and "self-deception" about who he was and his unfulfilled ambitions. The painting, a rare survivor of her early works, has been shown at Tate Modern.[2]

During the Depression, Neel was one of the first artists to work for the Works Progress Administration.[8] At the end of 1933, Neel was hired to make a painting every six weeks. She had been living in poverty.[5] She had an affair with a man named Kenneth Doolittle who was a heroin addict and a sailor. In 1934, he set afire 350 of her watercolors, paintings and drawings.[2][nb 1] At this time, her husband Carlos proposed to reunite, although in the end the couple neither reunited nor officially filed for divorce.[9]

Her world was composed of artists, intellectuals, and political leaders of the Communist Party, all of whom became subjects for her paintings. Her work glorified subversion and sexuality, depicting whimsical scenes of lovers and nudes, like a watercolor she made in 1935, Alice Neel And John Rothschild In The Bathroom, which showed the naked pair peeing.[2] In the 1930s Neel gained a degree of notoriety as an artist, and established a good standing within her circle of downtown intellectuals and Communist Party leaders. While Neel was never an official Communist Party member, her affiliation and sympathy with the ideals of Communism remained constant.

In 1939 Neel gave birth to her first son, Richard, the child of Jose Santiago, a Puerto Rican night-club singer whom Neel met in 1935. Neel moved to Spanish Harlem. She began painting her neighbors, particularly women and children. José left Neel in 1940.

Post-war years

Neel's second son, Hartley, was born in 1941 to Neel and her lover, the communist intellectual Sam Brody. During this Forties, Neel made illustrations for the Communist publication, Masses & Mainstream, and continued to paint portraits from her uptown home. However, in 1943 the Works Progress Administration ceased working with Neel, which made it harder for the artist to support her two sons.[10] During this time Neel would shoplift and was on welfare to help make ends meet.[11] Between 1940 and 1950, Neel’s art virtually disappeared from galleries, save for one solo show in 1944. In the 1950s, Neel’s friendship with Mike Gold and his admiration for her social realist work garnered her a show at the Communist-inspired New Playwrights Theatre. In 1959, Neel even made a film appearance after the director Robert Frank asked her to appear alongside a young Allen Ginsberg in his classic Beatnik film, Pull My Daisy. The following year, her work was first reproduced in ARTnews magazine.

Recognition

Toward the end of the 1960s, interest in Neel’s work intensified. The momentum of the women's movement led to increased attention, and Neel became an icon for feminists. In 1970, she was commissioned to paint the feminist activist Kate Millett for the cover of Time magazine. Millett refused to sit for Neel; consequently, the magazine cover was based off a photograph.[12]

By the mid-1970s, Neel had gained celebrity and stature as an important American artist. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter presented her with a National Women’s Caucus for Art award for outstanding achievement. Neel’s reputation was at its height at the time of her death in 1984.

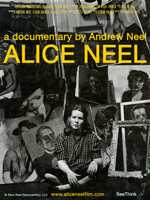

Neel's life and works are featured in the documentary Alice Neel, which premiered at the 2007 Slamdance Film Festival and was directed by her grandson, Andrew Neel. The film was given a New York theatrical release in April of that year.

Exhibitions

In 1974, Neel's work was given a retrospective exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art,[2] and posthumously, in the summer of 2000, also at the Whitney. The first exhibition dedicated to Neel's works in Europe was held in London in 2004 at the Victoria Miro Gallery. Jeremy Lewison, who had worked at the Tate, was the curator of the collection.[2] In 2001 the Philadelphia Museum of Art organized a retrospective of her art entitled Alice Neel.[13] She was the subject of a retrospective entitled Alice Neel: Painted Truths organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in Texas, which was on view from March 21-June 15, 2010.[14] The exhibition traveled to Whitechapel Gallery, London, and Moderna Museet Malmö, Malmö, Sweden.[15] In 2013, the first major presentation of the artist’s watercolors and drawings was on view at Nordiska Akvarellmuseet in Skärhamn, Sweden.[16]

Collections

Work by the artist is represented in major museum collections, including:[16]

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

- Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Moderna Museet, Stockholm

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- Museum of Modern Art, New York

- National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[17]

- National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.[18]

- Philadelphia Museum of Art[19]

- Tate, London

- Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut

- Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

- Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts

- Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut

Art market

The estate of Alice Neel is represented by David Zwirner, New York, Victoria Miro Gallery, London and Galerie Aurel Scheibler, Berlin, and is advised by Jeremy Lewison Ltd.

See also

- The Portrait Now that exhibited her self-portrait

- Elizabeth Neel, her granddaughter and an artist in her own right

Notes

References

- ↑ "Alice Neel", BBC, Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Suzie Mackenzie (May 28, 2004). "Heroes and wretches". The Guardian. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Shrimpton, editor, Delia Gaze ; picture editors, Maja Mihajlovic, Leanda (1997). Dictionary of women artists. London: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 1007. ISBN 1-884964-21-4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Biography", Aliceneel.com, Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 M. Therese Southgate (17 March 2011). The Art of JAMA: Covers and Essays from The Journal of the American Medical Association. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-975383-3.

- ↑ Munor, Eleanor (2000). Originals : American women artists (New ed., 1. Da Capo Press ed. ed.). Boulder, Colo.: Da Capo Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-306-80955-9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "Biography - 1920s", AliceNeel.com, Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ Hoban, Phoebe. "Portraits of Alice Neel's Legacy", The New York Times, Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ "Biography - 1930s", AliceNeel.com, Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ "Alice Neel", Smithsonian Institution's National Portrait Gallery, Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ Solomon, Deborah. "The Nonconformist", The New York Times, Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ Solomon, Deborah (29 December 2010). "The Nonconformist". The New York Times Company. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ↑ "Exhibitions - 2001", Philadelphia Museum of Art, Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ "Painted Truths", Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ www.AliceNeel.com "Alice Neel: Painted Truths". www.AliceNeel.com. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Alice Neel David Zwirner Gallery.

- ↑ National Gallery of Art. "Neel, Alice". Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ↑ "Self Portrait", Smithsonian Institution's National Portrait Gallery, Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ "Collections: Alice Neel", Philadelphia Museum of Art, Retrieved 13 November 2014.

Bibliography

- Hills, Patricia (1995). "Alice Neel", Harry N Abrams, Inc., New York. ISBN 0810913585.

- Hoban, Phoebe (2010). The Art of Not Sitting Pretty, St. Martin's Press, New York. ISBN 0312607482.

- Walker, Barry, et al., Alice Neel: Painted Truths, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. ISBN 0300163320.

External links

- Alice Neel site

- Alice Neel film site

- Finding aid to the Alice Neel papers, 1933-1983 in the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|