Ali-paša Rizvanbegović

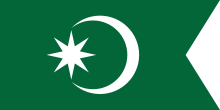

Ali Rizvanbegović (1783 – 20 March 1851)[1] Turkish: Ali Rıdvanoğlu Paşa, was a Herzegovinian Ottoman captain (administrator) of Stolac from 1813 to 1833 and the semi-independent ruler (vizier) of the Herzegovina Eyalet from 1833 to 1851.

Early life

Ali-paša Rizvanbegović was born in the Begovina neighbourhood of Stolac in 1783. In 1813, being thirty years old, he was appointed as the Captain of his native city, a position he would hold until 1833 and which would turn out to have a crucial importance.

Opposition to the Bosnian uprising

Ali-paša Rizvanbegović was strongly opposed to the 1831 Bosnian uprising, led by Husein Gradaščević. He made Stolac a rallying point for the forces loyal to the Ottoman government – in conjunction with fellow loyalist Smail-aga Čengić, Captain of Gacko, who acted similarly in his own place.

In the early phase of the uprising, Ali-paša gave refuge in Stolac to the Ottoman governor Namik-paša, who had fled after the rebels' capture of Travnik. A rebel army set out from Sarajevo to attack Stolac, but this was put on hold when the rebels found that Namik-paša had left the city.

In the final months of 1831, however, the rebels launched an overall offensive against the loyalist captains, aimed at ending domestic opposition to the uprising and bringing the whole of Herzegovina under rebel rule. Rebel forces led by the captain of Livno, Ibrahim-beg Fidrus, attacked and defeated Sulejman-beg, captain of Ljubuški.

That victory placed most of Herzegovina in rebel hands, leaving Stolac isolated and under a rebel siege. Ali-paša Rizvanbegović conducted well the city's defense. In early March 1832 he received information that the Bosnian rebels' ranks were depleted due to the winter and broke the siege, counterattacking the rebels and dispersing their forces. At the time, a rebel force under the command of Mujaga Zlatar had been sent from Sarajevo with the intention of reinforcing the force besieging Stolac – but was recalled by the rebel leadership on 16 March 1832, after news arrived of an impending major Ottoman offensive.

With the Ottoman armies closing in on Sarajevo in a following months, Ali-paša Rizvanbegović advanced with his own forces, as did his fellow loyalist Smail-aga Čengić of Gacko. Their armies arrived on 4 June at Stup, a small locality on the road between Sarajevo and Ilidža, where a long, intense battle had already been going on between the main Ottoman armies and the rebel army led by Gradaščević himself.

The Herzegovinian loylist troops broke through defenses Gradaščević had set up on his flank and joined the fighting. Overwhelmed by the unexpected attack from behind, the rebel army was forced to retreat into the city of Sarajevo itself, where their leaders decided that further military resistance would be futile. The imperial army entered Sarajevo on 5 June and Gradaščević went into exile in Austria.

Vizier of Herzegovina

His loyalty to the Ottoman government in the moment of crisis, and his considerable military success in that cause, clearly entitled Ali-paša Rizvanbegović to a suitable reward. In 1833 Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II conferred on Ali-paša the title of Vizier, as well as giving him the choice of which territory he wanted to rule. Ali-paša then asked the Sultan to separate Herzegovina from Pashaluk of Bosnia, creating the new Pashaluk of Herzegovina and make him its Vizier, a with duly fulfilled by the Sultan. Given that Bosnia had just broken out in a mass uprising while a considerable part of Herzegovina remained loyal, the separation – and the rewarding of Herzegovina with a greater amount of autonomy – were an obvious Imperial policy.

However, though at the time Ali-paša hoped to make this position as Vizier of Herzegovina hereditary in his family, it would in fact only last for his own lifetime, being abolished at his death.

Proclamation

In 1833, the new Vizier of Herzegovina came to Mostar, announcing to the people:

"Our honest Emperor loves me and therefore made me a third near himself. He offered me to become a vizier of wherever I wanted, but I did not want to be a Vizier of anything but of Herzegovina, separated from the Pashaluk of Bosnia. These are the counties of Herzegovina: Prijepolje, Pljevlja with Kolašin and Šaranci with Drobnjak, Čajniče, Nevesinje, Nikšić, Ljubinje-Trebinje, Stolac, Počitelj, Blagaj, Mostar, Duvno and half of the county of Konjic which is on this side of Neretva. This was given to me, my children and my kin, and I have done this to prevent that some bad pasha rule over Herzegovina. I thought that it is better that I, as a native, should rule over Herzegovina, instead of some alien – nobody could be fiend to his own house. I will judge everybody by justice..."

Ali-paša further stated:

"From today on, nobody need any longer go to the Emperor in Istanbul. Here in Mostar is your Istanbul, and here in Mostar is your Emperor."

Administration of Herzegovina 1833–1851

As the new Vizier of Herzegovina from 1832 to 1851, Ali-paša Rizvanbegović made special efforts to promote agriculture and attempted to recuperate the strong economy of the once famed Bosnia Eyalet. During the administration of Ali-paša Rizvanbegović olives, almonds, coffee, rice, citrus fruits and new vegetables became staple food sources.[2]

Death

While Ali-paša Rizvanbegović hoped to establish a long lasting hereditary Viziership, he was executed on 20 March 1851 by Omar Pasha in a humiliating and cruel manner[3] and the Pashaluk of Herzegovina was abolished and its territory was merged with the Pashaluk of Bosnia, forming a new entity known as Bosnia and Herzegovina.

References

- ↑ "Dalmacijom u dolinu Neretve; Page 397" (PDF). Metković. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ http://books.google.com.pk/books?id=hUneqCTh2YIC&pg=PA17&dq=husein+kapetan&hl=en&sa=X&ei=5skjT6bWLc-cOu3QmagI&ved=0CFUQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=olives%2C%20almonds%2C&f=false

- ↑ http://books.google.com.pk/books?id=hUneqCTh2YIC&pg=PA17&dq=husein+kapetan&hl=en&sa=X&ei=5skjT6bWLc-cOu3QmagI&ved=0CFUQ6AEwBg#v=snippet&q=latas%20had%20him%20killed&f=false

Sources

- Dr. Lazar Tomanović, Petar Drugi Petrović – Njegoš kao vladalac, Novi Sad – Srbinje, 2004.

- Andric, Ivo. The Damned Yard and Other Short Stories. Belgrade: Dereta, 2007.

See also

- Alipasini Izvori

- Pashaluk of Herzegovina

- Herzegovina

- History of Herzegovina

- History of Bosnia and Herzegovina

External links

|