Alferd Packer

| Alfred Packer | |

|---|---|

|

Alfred Packer | |

| Born |

Alfred Griner Packer January 21, 1842 Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, US |

| Died |

April 23, 1907 (aged 65) Jefferson County, Colorado |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Big Headed Cannibal |

| Known for | Accused of cannibalism |

Alfred G. "Alferd" Packer (January 21, 1842 – April 23, 1907)[1] was an American prospector who confessed to cannibalism during the winter of 1873–1874. He and 5 other men attempted to travel through the high mountains of Colorado during the peak of a harsh winter. They ran out of food when the snow became too deep for travel. Alfred confessed to eating some of his companions and using their flesh to survive his trek out of the mountains two months later. He hid from justice for 9 years before being tried and convicted of murder and sentenced to death. Packer won a retrial and was eventually sentenced to 40 years in prison for manslaughter.[2] A biopic of his life, The Legend of Alfred Packer, was made in 1980.

Packer's life

He was born as Alfred Griner Packer in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, one of three children of James Packer and his wife Esther Griner.[3] By the early 1850s, James Packer had moved his family to Lagrange County, Indiana, where he worked as a cabinet maker.[4]

Alfred Packer served in the Union Army in the American Civil War, enlisting on April 22, 1862 at Winona, Minnesota in Company F, 16th U. S. Infantry Regiment, giving his occupation as a shoemaker. He was honorably discharged due to epilepsy eight months later at Fort Ontario, New York.[5] He moved south and on June 25, 1863, enlisted in Company L, 8th Iowa Cavalry Regiment at Ottumwa, Iowa; however, he was discharged at Cleveland, Tennessee on April 22, 1864, for the same reason. He then traveled to the Rockies and worked at mining related jobs for 9 years[6]

In November 1873, Packer was in a party of 21 men who left Provo, Utah, heading for the Colorado gold country around Breckenridge. On January 21, 1874 he met Chief Ouray, known as the White Man's Friend, near Montrose, Colorado. Chief Ouray recommended they postpone their expedition until spring, since they were likely to encounter dangerous winter weather in the mountains.

Ignoring Ouray's advice, Packer and five others left for Gunnison, Colorado, on February 9. Besides Packer, the group was made up of Shannon Wilson Bell, James Humphrey, Frank "Reddy" Miller, George "California" Noon, and Israel Swan.

The prospectors became hopelessly lost and were snowbound in the Rocky Mountains, soon running out of food. Packer later made three confessions which differed considerably in their description of what had happened. In the last, he claimed he went scouting and came back to find Shannon Bell roasting human flesh. When Bell rushed him with a hatchet, Packer shot him. Packer claimed Bell had gone mad and murdered the others.

On April 16, 1874, Packer arrived at Los Pinos Indian Agency near Gunnison. He spent some time in a saloon in Saguache, Colorado, where he met several of his original party. Packer claimed he had acted in self-defense, but his story was not believed. According to a local newspaper, the presiding judge, M.B. Gerry, said:

| “ | Stand up yah voracious man-eatin' sonofabitch and receive yir sintince. When yah came to Hinsdale County, there was siven Dimmycrats. But you, yah et five of 'em, goddam yah. I sintince yah t' be hanged by th' neck ontil yer dead, dead, dead, as a warnin' ag'in reducin' th' Dimmycratic populayshun of this county. Packer, you Republican cannibal, I would sintince ya ta hell but the statutes forbid it.[7] | ” |

Court records, however, reveal that Judge Gerry's prose was much more educated:

| “ | Close your ears to the blandishments of hope. Listen not to its fluttering promises of life. But prepare to meet the spirits of thy murdered victims. Prepare for the dread certainty of death.[8] | ” |

Packer signed a confession on August 5, 1874. He was jailed in Saguache, but he escaped soon afterwards.

On March 11, 1883, Packer was discovered in Cheyenne, Wyoming, living under the alias of "John Schwartze". He signed another confession on March 16. On April 6, a trial began in Lake City, Colorado, and seven days he was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to death. In October 1885, the sentence was reversed by the Colorado Supreme Court as being based on an ex post facto law. On June 8, 1886, Packer was sentenced to 40 years at another trial in Gunnison. At the time, this was the longest custodial sentence in U.S. history.[9]

On June 19, 1899, Packer's sentence was upheld by the Colorado Supreme Court. However, he was paroled on February 8, 1901, and went to work as a guard at the Denver Post. He died in Deer Creek, in Jefferson County, Colorado, reputedly of "Senility - trouble & worry" at the age of 65. Packer is widely rumored to have become a vegetarian before his death. He was buried in Littleton, Colorado. His grave is marked with a veteran's tombstone listing his original regiment in 1862.[10]

Recent investigations

On July 17, 1989, 115 years after Packer allegedly consumed his companions, an exhumation of the five bodies was undertaken by James E. Starrs, then a professor of law specializing in forensic science at George Washington University. Following an exhaustive search for the precise location of the remains at Cannibal Plateau in Lake City, Colorado, Starrs and his colleague Walter H. Birkby concluded, "I don't think there will ever be any way to scientifically demonstrate cannibalism. Cannibalism per se is the ingestion of human flesh. So you'd have to have a picture of the guy actually eating."[11]

In 1994, David P. Bailey, Curator of History at the Museum of Western Colorado, undertook an investigation to turn up more conclusive results than Starrs'. In the Audrey Thrailkill collection of firearms owned by the museum was a Colt revolver that had reportedly been found at the site of Packer's alleged crime. Exhaustive investigation into the pistol's background turned up documents from the time of the trial: "A Civil War veteran that visited the crime scene stated that Shannon Bell had been shot twice and the other victims were killed with a hatchet. Upon careful study of Bell, he noticed a severe bullet wound to the pelvic area and that Bell's wallet had a bullet hole through it." This seems to corroborate Packer's claim that Bell had killed the other victims and that Packer shot Bell in self-defense.[12]

By 2000, Bailey had not yet proven a link between the antique pistol and Alfred Packer, but he discovered that forensic samples from the 1989 exhumation had been archived, and analysis in 2001 with an electron microscope by Dr. Richard Dujay at Mesa State College found microscopic lead fragments in the soil taken from under Shannon Bell's remains that were matched by spectrograph with the bullets remaining in what was indeed Packer's pistol.[12] While it appears certain that Bell was killed by a gunshot, the question of whether it was murder remains unanswered.

Popular culture

In the early 1960s, folk singer Phil Ochs wrote the song "The Ballad of Alferd Packer", documenting the events of the expedition and its aftermath. Ochs' use of humor in the song is typical of the seemingly light-hearted ongoing attitude regarding Packer and his alleged crimes. Although the track never appeared on any of Ochs' studio or live album releases, it has appeared on several compilations issued since his death in 1976, most recently on the "On My Way" compilation of demos from 1963, released in 2010.

In 1968, students at the University of Colorado Boulder named their new cafeteria grill the "Alferd G. Packer Memorial Grill" with the slogan "Have a friend for lunch!" Students can order an "El Canibal" beefburger and on the wall is a giant map outlining Packer's travels through Colorado.[13] It has since been renamed the Alferd Packer Restaurant & Grill.

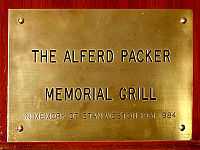

In 1977 the US Secretary of Agriculture, Bob Bergland, attempted to terminate a contract for the department's cafeteria food service, but was prevented by the General Services Administration (GSA). To embarrass the GSA, Bergland and his employees convened a press conference on 10 August 1977 to unveil a plaque naming the executive cafeteria "The Alferd Packer Memorial Grill", announcing that Packer's life exemplified the spirit and fare of the cafeteria and would "serve all mankind". The event was covered on ABC-TV Evening News by Barbara Walters.[14] The stratagem was successful and the contracts were terminated soon thereafter. Magnanimous in victory, Bergland yielded to the bureaucratic objection that the plaque lacked official GSA authorization, and removed it. The plaque is currently displayed on the wall of the National Press Club's The Reliable Source members-only bar. It doubles as a memorial to Stanley Weston (1931–84), a man who worked at the USDA.[15] The Press Club's hamburger is called the "Alferd Packer Burger".

In 1990, country artist C.W. McCall (of "Convoy" fame) recorded a track on his album The Real McCall titled "Coming Back for More", which revived the legend and implied that Packer's ghost still haunts Lake City.

In 1990 the American death metal band Cannibal Corpse dedicated their debut album, Eaten Back to Life, to Packer. The following statement can be found in the inlay of this album: "This album is dedicated to the memory of Alfred Packer, the first American cannibal (R.I.P.)"

Macabre, the self-proclaimed Murder-Metal band from Chicago, released a song about Packer's trek for gold called "In the Mountains" from their Macabre Minstrels: Morbid Campfire Songs(2002) album.

In 1993, University of Colorado students Trey Parker and Matt Stone, co-creators of South Park, made a film called Cannibal! The Musical, based loosely on Packer's life, with Parker billed as "Juan Schwartz" (a variation of Packer's "John Schwartze"). The film was released commercially in 1996 by Troma Entertainment and produced as a stage play initially by Dad's Garage Theatre Company and by several other theatre companies since. Lesser known film adaptions include The Legend of Alfred Packer (1980) and the horror film, Devoured: The Legend of Alferd Packer (2005).

The annual Philadelphia Folk Festival features a dining tent emblazoned with the tongue-in-cheek moniker: "The Alfred E. Packer Memorial Dining Hall...serving humanity since 1874".

In The Piranha Club comic strip by Bud Grace, one of the madcap denizens of Bayonne, New Jersey is an old lady named "Alferda Packer, consumer advocate" who wages a humorously violent Carrie Nation-style crusade against unscrupulous business practices. One of her most frequent targets is her own son-in-law Dr. Enos Pork, a quack surgeon who bilks outrageous prices from his patients for the malpractice he performs on them.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The spelling of Alferd/Alfred Packer's name has been the source of much confusion over the years. Official documents give his name as Alfred Packer, although he may (according to one story) have adopted the name Alferd after it was wrongly tattooed on to one of his arms. Packer sometimes signed his name as "Alferd", sometimes as "Alfred", and is referred to by both names. In many documents, he is referred to simply as A. Packer or Al Packer.

- ↑ Nash, Robert Jay (1994). Alferd Packer. In Encyclopedia of Western Lawmen & Outlaws or Encyclopedia of Western Lawmen & Outlaws. Da Capo Press. pp. 250-251. ISBN 0-306-80591-X. Google Print. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ↑ Ancestry of Alfred Packer

- ↑ US Census, 1860, Lagrange Co., Indiana, page 9, residence #68

- ↑ Army Register of Enlistments 1862, #182, regular army

- ↑ Compiled Service Record of Alfred G. Parker, 8th Iowa Cavalry Regiment

- ↑ Alfred "Alferd" Packer: The Cannibal of Lake City, Colorado Retrieved May 22, 2008

- ↑ Mazulla, Fred and Mazulla, Jo. "THE SENTENCE OF ALFRED PACKER BY JUDGE M.B. GERRY, COPIED FROM THE DISTRICT COURT RECORDS" in Al Packer a Colorado Cannibal Denver? 1968 p. 20 (OCLC 449216)

- ↑ Simpson, A. W. B. (1984). Cannibalism and the Common Law: The Story of the Tragic Last Voyage of the Mignonette and the Strange Legal Proceedings to Which It Gave Rise. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-226-75942-5.

- ↑ "Alfred Packer at Find A Grave". Find A Grave. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ↑ Grove, Lloyd (1989). Just How Many Democrats Did Al Packer Eat? GWU Professor Digs Into the Legend. The Washington Post.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 David Bailey. "Alferd Packer". Museum of Western Colorado. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ↑ "Alferd Packer Grill". University of Colorado, Division of Student Affairs. University Memorial Center – University of Colorado Boulder. Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- ↑ "Packer / Agriculture Department Squabble". ABC -- TV news: Vanderbilt Television News Archive. 2011-08-10. Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- ↑ (ref. telecon April 27, 2007 between Kurt Riegel & Bob Bergland).

References

- Botkin, Benjamin A. (1957). A Treasury of American Anecdotes page 174 Man-Eating Packer Galahad Press

- Gantt, Paul H (1952). The Case of Alfred Packer, The Man-Eater. Denver: University of Denver Press.

- Kushner, Ervan F (1980). Alferd G. Packer, Cannibal! Victim? Frederick, Co.: Platte 'N Press.

- Ramsland, Katherine (2005). "ALFRED PACKER: THE MANEATER OF COLORADO". http://www.crimelibrary.com/serial_killers/history/alfred_packer/index.html

- "The Alferd Packer Grill at the University of Colorado". http://www.colorado.edu/umc/dining/alferd-packer

- http://www.nndb.com/lists/843/000106525/

External links

- Museum of Western Colorado (2009). Solving the American West's Greatest Mystery - Was Alferd Packer Innocent of Murder?

- The Alfred Packer Collection at the Colorado State Archives. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- Packer on the Littleton, Colorado site.

- Internet Movie Database (2012). Alferd Packer: The Musical. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- MuseumTrail.org (2002). The Story of Alferd E. Packer. Retrieved 2005-04-13.

- Ochs, Phil. The Ballad Of Alferd Packer. Retrieved 2005-04-13.

- University of Colorado Boulder Memorial Center (2014). The Alferd Packer Resaurant & Grill. Retrieved 2014-09-16.

- Alfred Packer at Find a Grave

|