Alexei Navalny

| Alexei Navalny | |

|---|---|

Alexei Navalny in 2012 | |

| Born |

Alexei Anatolievich Navalny 4 June 1976 Butyn, Odintsovsky District, Moscow Oblast, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Residence | Moscow |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Alma mater |

Peoples' Friendship University of Russia Finance University under the Government of the Russian Federation Yale University |

| Occupation | Lawyer, activist, politician |

| Organization | The Anti-Corruption Foundation |

| Known for | Political and social activism, blogging |

Political party |

Progress Party (2013–present) Yabloko (2000–2007) |

| Movement |

Russian Opposition Coordination Council various liberal, civic nationalist and national democrat organizations |

| Opponent(s) | Vladimir Putin and United Russia party |

Board member of | Aeroflot (2012–2013) |

| Religion | Russian Orthodox |

| Spouse(s) | Yulia Navalnaya |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Yale World Fellow (2010) |

| Website | |

|

navalny | |

|

Alexei Navalny's voice

recorded August 2013 |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Alexei Anatolievich Navalny (Russian: Алексе́й Анато́льевич Нава́льный, Russian pronunciation: [ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej ɐnɐˈtolʲɪvʲɪtɕ nɐˈvalʲnɨj]), born 4 June 1976) is a Russian lawyer, political and financial activist,[1] and politician. Since 2009, he has gained prominence in Russia, and in the Russian and international media, as a critic of corruption and of Russian President Vladimir Putin. He has organized large-scale demonstrations promoting democracy and attacking political corruption, Putin, and Putin's political allies; he has run for a political office on the same platform. In 2012, The Wall Street Journal described him as "the man Vladimir Putin fears most".[2]

A self-described nationalist democrat, Navalny is a Russian Opposition Coordination Council member and the leader of the political party Progress Party, formerly People's Alliance.[3] In September 2013 he ran in the Moscow mayoral election, supported by the RPR-PARNAS party. He came in second, with 27% of the vote, losing to incumbent mayor Sergei Sobyanin, a Putin appointee. His vote total was much higher than political analysts had expected, but Navalny and his allies insisted that the actual number was still higher, and that authorities had committed election fraud in order to prevent a runoff election from taking place.[4]

Navalny came to prominence via his blog, hosted on the website LiveJournal, which remains his primary method of communicating with the public. He has used his blog to attack Putin and his allies, to organize political demonstrations, to post documents showing Putin and his allies to be engaged in unsavory behavior and, most recently, to promote his campaigns for office. He has also been active in other media: most notably, in a 2011 radio interview he described Russia's ruling party, United Russia, as a "party of crooks and thieves", which soon became a popular epithet.[5]

Navalny has been arrested numerous times by Russian authorities, most seriously in 2012, when federal authorities accused him of three instances of embezzlement and fraud, all of which he denied.[6] In July 2013 he was convicted of embezzlement and was sentenced to five years in a corrective labor colony.[7][8] Russia's Memorial Human Rights Center recognized Navalny as a political prisoner.[9] Navalny was released from prison a day after sentencing.[10] The prison fine was suspended in October 2013.[11] In February 2014 Navalny and his brother were prosecuted on embezzlement charges, and Navalny was placed under house arrest and restricted from communicating with anyone but his family; he was sentenced in December 2014 with another suspended prison term of 3.5 years, and his brother received an actual 3.5-year prison sentence.[12]

Early life and career

Navalny is of Russian and Ukrainian descent.[13] His father Anatoliy Navalny is from Zalissia, a village in Ivankiv Raion, Kiev Oblast, Ukraine. Navalny grew up in Obninsk about 100 km southwest of Moscow, but spent his childhood summers with his grandmother in Ukraine.[13][14]

Navalny graduated from the Peoples' Friendship University of Russia in 1998 with a law degree. He then studied securities and exchanges at the Finance University under the Government of the Russian Federation.[15][16]

In 2000, Navalny joined the Russian United Democratic Party Yabloko,[17] where he was a member of the Federal Political Council of the party. In 2002, he was elected to the regional council of the Moscow branch of Yabloko.[18]

Early activism

As acting Deputy Chief of the Moscow branch of Yabloko, Navalny stated that the party supported the nationalist 2006 Russian March but that Yabloko condemned "any ethnic or racial hatred and any xenophobia" and called on police to oppose "any Fascist, Nazi, xenophobic manifestations".[19] The march was widely opposed by the Moscow Bureau for Human Rights,[20] and the Russian Jewish community headed by rabbi Berel Lazar,[21] and participation from the Movement Against Illegal Immigration (the main organizer of the rally), the Eurasian Youth Union, the Communist Youth Vanguard, the National State Party of Russia, the National Patriotic Front "Memory", the "Truth" Community, the Russian National Union, the Russian Social Movement, and the "Russian Order" Movement.[22]

In December 2007, a meeting was held by the Bureau of the Yabloko party, on the issue of Navalny's exclusion from the party, with demands of "the immediate resignation of party chairman and all his deputies, and the re-election of at least 70% of the Bureau".[23] Navalny was consequently expelled from Yabloko "for causing political damage to the party; in particular, for nationalist activities".[24]

Navalny is a minor stockholder in several major Russian state-related corporations and some of his activities are aimed at making the financial properties of these companies transparent. This is required by law, but there are allegations that some of the top managers of these companies are involved in thefts and are obscuring transparency.[25] Other activities deal with wrongdoings by Russian police, such as Sergei Magnitsky's case, improper usage of state's budget funds, quality of state services and so on.

In October 2010, Navalny was the decisive winner of virtual "Mayor of Moscow elections" held in the Russian Internet by Kommersant and Gazeta.ru. He received about 30,000 votes, or 45%, with the closest rival being "Against all candidates" with some 9,000 votes (14%), followed by Boris Nemtsov with 8,000 votes (12%) out of a total of about 67,000 votes.[26]

In November 2010, Navalny published[27] confidential documents about Transneft's auditing. According to the Navalny's blog, about four billion dollars were stolen by Transneft's leaders during the construction of the Eastern Siberia – Pacific Ocean oil pipeline.[28][29]

In December 2010, Navalny announced the launch of the RosPil project, which seeks to bring to light corrupt practices in the government procurement process.[30] The project takes advantage of existing procurement regulation that requires all government requests for tender to be posted online. Information about winning bids must be posted online as well.

In February 2011, in an interview with the radio station finam.fm, Navalny called the main Russian party, United Russia, a "party of crooks and thieves".[5] In May 2011, the Russian government began criminal investigation into Navalny, widely described in Western media as "revenge" and by Navalny himself as "a fabrication by the security services".[5][31][32] Meanwhile, "crooks and thieves" became a popular nickname for the party.[33]

In May 2011 Navalny launched the RosYama project, which allowed individuals to report potholes and track government responses to complaints.[34]

In August 2011 Navalny publicized papers related to a scandalous real estate deal[35] between Hungarian and Russian governments.[36][37] According to the papers, Hungary sold a former embassy building in Moscow for US$21 million to an offshore company of V. Vekselberg, who immediately resold it to the Russian government for $111 million. Irregularities in the paper trail implied a collusion. Three Hungarian officials responsible for the deal were detained in February 2011.[38] It is unclear whether any official investigation was conducted on the Russian side.

Involvement in 2011 Russian legislative election

In December 2011, after parliamentary elections and accusations of electoral fraud,[39] some 6,000 gathered in Moscow to protest the fraud, and some 300 were arrested including Navalny. After a period of uncertainty, Navalny was produced at court and thereafter sentenced to the maximum 15 days "for defying a government official". Alexei Venediktov called the arrest "a political mistake: jailing Navalny transforms him from an online leader into an offline one".[40] Navalny was kept in the same prison as several other activists, including Ilya Yashin and Sergei Udaltsov, the unofficial leader of the Vanguard of Red Youth, a radical Russian communist youth group. Udaltsov has gone on hunger strike to protest against the conditions.[41]

Navalny was arrested 5 December 2011, convicted and sentenced to 15 days in jail. Since his arrest, his blog has become available in English.[42] On 7 December, President Dmitry Medvedev's official Twitter account retweeted a statement by United Russia member Konstantin Rykov which claimed that "a person who writes in their blog the words 'party of crooks and thieves' is a stupid, cocksucking sheep". This retweet was quickly deleted and described as a mistake by the Kremlin, but garnered wide attention in the Russian blogosphere.[43]

In a profile published the day after his release, the BBC described Navalny as "arguably the only major opposition figure to emerge in Russia in the past five years".[44]

Involvement in 2012 Russian presidential election

On his release on 20 December 2011, Navalny called on Russians to unite against Putin, who Navalny said would try to snatch victory in the 4 March 2012 presidential election.[45]

Navalny told reporters on his release that it would be senseless for him to run in the presidential elections because the Kremlin would not allow them to be fair. But he said that if free elections were held, he would "be ready" to run.[45] He then on 24 December helped lead a demonstration much larger than the post-election one (50,000 strong, in one Western-media account), telling to the "wildly cheering crowd", "I see enough people to take the Kremlin right now".[46]

Post-2012-election government battles

In March, after Putin was elected president, Navalny helped lead an anti-Putin rally in Moscow's Pushkin Square, attended by between 14,000 and 20,000 people. After the rally, Navalny was detained by authorities for several hours, then released.[47]

On 8 May, the day after Putin was inaugurated, Navalny and another opposition leader, Sergei Udaltsov, were arrested after an anti-Putin rally at Clean Ponds, and were each given 15-day jail sentences.[48] In response, Amnesty International designated the two men prisoners of conscience.[49] On 11 June 2012, Moscow prosecutors conducted a 12-hour search of Navalny's home, office and a search of the apartment of one of Navalny's relatives. The searches were done as part of a broader investigation into the clashes between opposition activists and riot police which happened on 6 May.[50] Soon afterwards, some of Navalny's personal emails were posted online by a pro-government blogger.[51]

In May 2012, Navalny accused Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov of corruption, stating that companies owned by Roman Abramovich and Alisher Usmanov had transferred tens of millions of U.S. dollars to Shuvalov's company, allowing Shuvalov to share in the profit from Usmanov's purchase of the British steel company Corus.[52][53] Navalny posted scans of documents to his blog showing the money transfers.[53] Usmanov and Shuvalov stated the documents Navalny had posted were legitimate, but that the transaction had not represented a violation of Russian law. Shuvalov stated, "I unswervingly followed the rules and principles of conflict of interest. For a lawyer, this is sacred".[52]

On 4 June 2012, Navalny was ordered by Moscow's Lyublinsky District Court to pay 30,000 rubles ($900) as compensation for "moral harm" to United Russia State Duma Deputy Vladimir Svirid, after Svirid filed charges against Navalny for comments he made in an article written for Esquire magazine about the United Russia party: "In United Russia, there are people I come across that I generally like. But if you have joined United Russia, you are still a thief. And if you are not a thief, then you are a crook, because you use your name to cover the rest of the thieves and crooks." Svirid had originally sought one million rubles in the case.[54]

In July 2012, Navalny posted documents on his blog allegedly showing that Alexander Bastrykin, head of the Investigative Committee of Russia and a Putin ally, owned an undeclared business in the Czech Republic. The posting was described by the Financial Times as Navalny's "answering shot" for having had his emails leaked during his arrest in the previous month.[51]

2012 embezzlement and fraud charges

On 30 July 2012, the Investigative Committee charged Navalny with embezzlement. The committee stated that he had conspired to steal timber from Kirovles, a state-owned company in Kirov Oblast in 2009, while acting as an adviser to Kirov's governor Nikita Belykh.[52][55] Investigators had closed a previous probe into the claims for lack of evidence.[56] Navalny was released on his own recognizance but instructed not to leave Moscow.[52]

Navalny described the charges as "weird" and unfounded.[56] He stated that authorities "are doing it to watch the reaction of the protest movement and of Western public opinion ... So far they consider both of these things acceptable and so they are continuing along this line".[52] His supporters protested before the Investigative Committee offices.[55]

Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt tweeted that "We should be concerned with attempts in Russia to silence fierce opposition activist Alexei Navalny".[55] The New York Times called it "the Kremlin's most direct measure to date against a leader of the protest movement that erupted here in December [2011]" and suggested that "the Kremlin's eagerness to limit Mr. Navalny's impact now outweighs the risk of a political backlash".[52] Al Jazeera described the charge as part of a broader trend of cracking down on dissent, connecting it to a recent bill in the Russian parliament to substantially increase fines on unauthorized protests and the trial of three members of the feminist punk-rock collective Pussy Riot.[56]

In late December 2012, Russia's federal Investigative Committee asserted that Allekt, an advertising company headed by Navalny, defrauded the Union of the Right Forces (SPS) political party in 2007 by taking 100 million rubles ($3.2 million) payment for advertising and failing to honor its contract. If charged and convicted, Navalny could be jailed for up to 10 years. "Nothing of the sort happened – he committed no robbery", Leonid Gozman, a former SPS official, was quoted as saying. Earlier in December, "the Investigative Committee charged ... Navalny and his brother Oleg with embezzling 55 million rubles ($1.76 million) in 2008–2011 while working in a postal business". Navalny, who denied the allegations in the two previous cases, sought to laugh off news of the third inquiry with a tweet stating "Fiddlesticks ...".[6]

In April 2013, Loeb&Loeb LLP issued "An Analysis of the Russian Federation's prosecutions of Alexei Navalny", a paper detailing Investigative Committee accusations.[57] The paper concludes that "the Kremlin has reverted to misuse of the Russian legal system to harass, isolate and attempt to silence political opponents".

Conviction

The Kirovles trial commenced in the city of Kirov on 17 April 2013.[58] On 18 July 2013, Navalny was sentenced to five years in jail for embezzlement.[7] Navalny was found guilty in misappropriating about 16 million rubles[59] ($500,000) worth of lumber from a state-owned company.[60] The sentence read by the judge Sergey Blinov was textually the same as the request of the prosecutor, with the only exception that Navalny was given five years, and the prosecution requested six years.[61]

Reaction

Navalny's wife Yulia Navalnaya stated, "if someone hopes Alexei's investigations will cease, that is not the case ... We will win".[62]

Navalny's arrest was criticized by a number of prominent Russians, including the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, who called it "proof that we do not have independent courts",[63] and former Finance Minister and close Putin ally Aleksei Kudrin, who stated that it was "looking less like a punishment than an attempt to isolate him from social life and the electoral process".[62][64] It was also criticized by novelist Boris Akunin,[64] and jailed Russian oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who called it similar to the treatment of political opponents during the Soviet era.[62]

Other prominent Russians had different reactions: Vladimir Zhirinovsky, leader of the nationalist LDPR, called the verdict "a direct warning to our 'fifth column'" and continued "This will be the fate of everyone who is connected with the West and works against Russia".[62] Duma Vice-Speaker Igor Lebedev stated that he did not understand the "fuss about an ordinary case". He added that "If you are guilty before the law, then whoever you were – a janitor, a homeless man or a president – you have to answer for your crimes in full accordance with the Criminal Code."[65]

A variety of countries and international organizations condemned the verdict. United States Department of State Deputy Spokesperson Marie Harf stated that the U.S. was "very disappointed by the conviction and sentencing of opposition leader Aleksey Navalniy".[66] The U.S. Ambassador to Russia, Michael McFaul, followed up by stating that the trial had "apparent political motivations".[62] A spokesperson for European Union High Representative Catherine Ashton said that the outcome of the trial "raises serious questions as to the state of the rule of law in Russia".[62][67]

Release

In the evening after the sentencing the Prosecutor's Office appealed the sentence in the part which prescribed Navalny and Ofitserov to be jailed, arguing that until the higher court affirmed the sentence, the sentence is not valid. Next morning, the appeal was granted. Navalny and Ofitserov were released on 19 July 2013 awaiting the hearings of the higher court.[68] The prosecutor's request decision was described "unprecedented" by experts.[69]

Probation

The prison sentence was suspended by a court in Kirov in 16 October 2013, still being a burden for his political future.[11]

October 2012 arrest

Following the alleged kidnapping and torture of opposition activist Leonid Razvozzhayev from Kiev, Ukraine, Navalny was arrested along with Sergei Udaltsov and Ilya Yashin while attempting to join a Moscow protest on Razvozzhayev's behalf on 27 October 2012. The three were charged with violating public order, for which they could be fined up to 30,000 rubles ($900) or given 50 hours of community service.[70]

Presidential candidacy

On 4 April 2013, Navalny announced his intention to run for the presidency.[71] Navalny described his presidential program as "not to lie and not to steal".[72]

According to polls conducted by the Levada Center, Navalny's recognition among the Russian population stood at 37% as of April 2013.[73] Out of those who were able to recognize Navalny, 14% would either "definitely" or "probably" support his presidential run.[74]

Moscow mayoral candidacy

In 2010, after the long-standing mayor of Moscow Yuri Luzhkov's resignation, then-President of Russia Dmitry Medvedev appointed Sergey Sobyanin for a five-year term. After the protests sparked in December 2011, Medvedev responded to that by a series of measures supposed to make political power more dependent on voters and increase accessibility for parties and candidates to elections; in particular, he called for re-establishing elections of heads of federal subjects of Russia,[75] which took effect on 1 June 2012.[76] On 14 February 2013, Sobyanin declared the next elections would be held in 2015, and a snap election would be unwanted by Muscovites,[77] and on 1 March, he proclaimed he wanted to run for a second term as a mayor of Moscow in 2015.[78]

Declaration of an upcoming election

On 30 May, Sobyanin argued an elected major is an advantage for the city compared to an appointed one,[79] and on 4 June, he announced he would meet the President Vladimir Putin and ask him for a snap election, mentioning the Muscovites would agree the governor elections should take place in the city of Moscow and the surrounding Moscow Oblast simultaneously.[80] On 6 June, the request was granted,[81] and the next day, the Moscow City Duma appointed the election on 8 September, the national voting day.[82]

On 3 June, Navalny announced he would run for the post.[83] To become an official candidate, he would need either seventy thousand signatures of Muscovites or to be pegged for the office by a registered party, and then collect 110 signatures of municipal deputies from 110 different subdivisions (three quarters of Moscow's 146).[84] Navalny chose to be pegged by a party, RPR-PARNAS (which did peg him, but this move sharpened relations within the party; after one of its three co-chairmen and the original founder, Vladimir Ryzhkov, had left the party, he said this had been one of the signs the party was "being stolen from him"[85]). Among the six candidates who were officially registered as such, only two (Sobyanin and Communist Ivan Melnikov) were able to collect the required number of the signatures themselves, and the other four were given a number of signatures by the Council of Municipal Formations to overcome the requirement (Navalny accepted 49 signatures, and other candidates accepted 70, 70, and 82 ones).[86]

On 17 July, Navalny was registered as one of the six candidates for the Moscow mayoral election.[87] However, on 18 July, he was sentenced for a five-year prison term for the embezzlement and fraud charges that were declared in 2012. Several hours after his sentencing, he pulled out of the race and called for a boycott of the election.[88] However, later that day, the prosecution office requested the accused should be freed on bail and travel restrictions, since the verdict had not yet taken legal effect, saying they had previously followed the restrictions, Navalny was a mayoral candidate, and an imprisonment would thus not comply with his rule for equal access to the electorate.[89] Upon his return to Moscow after being freed pending an appeal, he vowed to stay in the race.[90] The Washington Post has speculated that his release was ordered by the Kremlin in order to make the election and Sobyanin appear more legitimate.[4]

Campaign

| Time | Sobyanin | Navalny | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| August 29–September 2 | 60,1 % | 21,9 % | [91] |

| August 22–28 | 63,9 % | 19,8 % | [92] |

| August 15–21 | 62,5 % | 20,3 % | [93] |

| August 8–14 | 63,5 % | 19,9 % | [94] |

| August 1–7 | 74,6 % | 15,0 % | [94] |

| July 25–31 | 76,2 % | 16,7 % | [95] |

| July 18–24 | 76,6 % | 15,7 % | [96] |

| July 11–16 | 76,2 % | 14,4 % | [97] |

| July 4–10 | 78,5 % | 10,7 % | [97] |

| June 27–July 3 | 77,9 % | 10,8 % | [97] |

Navalny's campaign was based mainly on fundraising: out of 103.4 million rubles (approximately $3.09 million as of the election day[lower-alpha 1]), the total size of his electoral fund, 97.3 million ($2.91 million) were transferred by individuals throughout Russia;[99] such a number is unprecedented in Russia.[100] It achieved a high profile through an unprecedentedly large campaign organization that involved around 20,000 volunteers who passed out leaflets and hung banners, as well as several campaign rallies a day around the city;[101] they were the main driving force for the campaign.[102] The New Yorker described the resulted campaign as "a miracle", along with Navalny's release on 19 July, the fundraising campaign, and the personality of Navalny himself.[103] The campaign received very little television coverage and did not utilize billboards;[102] Navalny accused Sobyanin for the former, calling for a TV Tsentr debate (he stated the channel is subsidized by the city and criticized it for not holding debates;[104] in the end of the campaign, he called this and a number of other federal channels to give him some coverage, which was ignored by all of them[105]).

During the campaign, Navalny claimed Sobyanin's paving roads with stones[106] and plantation[107] in the city showed corruption, and he claimed Sobyanin and his city workers steal Navalny banners.[108] Later, he announced the younger of the Sobyanin's daughters acquired a 173 million rubles ($5.27 million)[109] worth apartment, claiming this service apartment could not be legally privatized by Sobyanin.[110] He also claimed the other Sobyanin's daughter owned a 116 million rubles ($3.53 million) worth apartment, and her own business's clients were only the ministries where her father serviced.[111] He also asked Sobyanin to show a presidential written agreement with him being able to run for the term after he had just resigned, quoting a law on elections, suggesting such a document would be published if it existed.[112] The next day, pending no satisfactory reply, he applied to a court to delete Sobyanin from the list of candidates; later that day, the document was published.[113]

Navalny himself was blamed for having founded a firm in Montenegro, which was legally "active" during the elections.[114] Head of his campaign office Leonid Volkov originally suggested the information was added by hackers,[115] but both Navanly and Volkov later stated the statement was "preliminary".[116] Navalny explained he had the idea of starting a building business in the country in 2007, an idea he rejected far before the company was even founded. He ordered a graphologist expertise, which showed Navalny's signature in the documents of founding the firm was fake.[116]

Thanks to Navalny's strong campaign (and Sobyanin's weak one[101]), his result grew over time, weakening Sobyanin's, and in the end of the campaign, he declared the runoff election (to be conducted in none of the candidates receives at least 50% of votes) was "a hair's breadth away".[117]

Election results

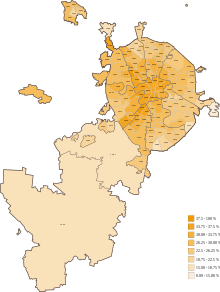

The largest sociological companies predicted (Levada Center was the only one not to have made any predictions; the data it had on 28 August, however, falls in line with other companies') Sobyanin would win the election, scoring 58% to 64% of the vote; they expected Navalny to receive 15–20% of the vote, and the turnout was to be 45–52%.[118] The final results of the voting showed Navalny received 27.24% of the vote, more than candidates appointed by the parties that received second, third, fourth, and fifth highest results during the 2011 parliamentary elections, altogether. Navalny fared better in the center and southwest of Moscow, which have higher income and education levels.[4] However, Sobyanin received 51.37% of the vote, which meant he won the election. The turnout was 32.03%.[119] The companies explained the differences arose from the fact Sobyanin's electorate did not vote, feeling their candidate was guaranteed to win.[118] Navalny claimed he would be the beneficiary of a high turnout.[120] Navalny's campaign office's measures predicted Sobyanin would score 49–51%, and Navalny would get 24–26% of votes.[118]

At 00:30, 9 September (the election count night), Navalny published a post saying, "One thousand stations are equipped with ballot paper processing systems, the results for which we were promised to get at 20:30. [...] Since the close of the voting, it has been four hours. We still do not have the turnout data for all voting stations. We still do not have the data for the ballot paper processing systems. But just five days ago, it was set in stone 'preliminary voting results of the Moscow mayoral elections will be known on September 8, at 22:00, and the name of the new mayor of Moscow will be announced before the midnight'. What is going on, dear Sergey Semyonovich [Sobyanin] and Vladimir Vladimirovich [Putin]? You cried the vote counting would be fair. Do not be afraid on the runoff election – it is not scary".[121] Later that day, Navalny publicly denounced the tally, saying, "We do not recognize the results. They are fake". Volkov said, "We do not appeal to everyone for insurgencies [...] we are open for negotiations, but we will not give away what is ours". The Sobyanin's office rejected the offer of a vote recount.[122] On 10 September, Navalny named a number of statistical irregularities and called for everyone to let him know of any voting irregularities,[123] and on 12 September, Navalny addressed district courts to overturn the result of the poll in 951 of 3611 election stations and the Moscow City Court to overturn the result of the whole poll.[124] The City Court rejected the assertion,[125] and after that, the district courts did the same. Navalny denounced these decisions, saying none of them were fair.[126]

The reaction to Navalny's result was mixed: Nezavisimaya Gazeta declared "The voting campaign turned a blogger into a politician",[127] and following an October 2013 Levada Center poll that showed Navalny made it to the list of potential presidential candidates among Russians, receiving a rating of 5%, Konstantin Kalachev, the leader of the Political Expert Group and a political technologist, declared 5% was not the limit for Navalny, and unless something extraordinary happened, he could become "a pretender for a second place in the presidential race".[128] On the other hand, The Washington Post published a column that stated the election was fair so the Sobyanin could show a clean victory, demoralizing the opposition, which could otherwise run for street protests.[129] Putin's press secretary Dmitry Peskov stated on 12 September, "His momentary result cannot testify his political equipment and does not speak of him as of a serious politician".[130] (When referring to Navalny, Putin never actually pronounced his name, referring to him as a "mister" or the like;[130] journalist Julia Ioffe took it for a sign of weakness before the opposition politician,[131] and Peskov later stated Putin never pronounced his name in order not to "give [Navalny] a part of his popularity".[132])

Yves Rocher case and home arrest

Since June 2012, Navalny had been a subject to travel restrictions because of the Kirovles trial, and since December 2012, he was a subject to another restriction, coming from the Yves Rocher trial. Unlike the former restriction, which allowed him to move across Moscow and the surrounding Moscow Oblast, the latter limited his movements to Moscow alone.[133] On 10 January 2014, however, he was found in Moscow Oblast, and the investigators announced the restrictions were broken.[134] Navalny declared he had been given the right to visit the territory of the Oblast some time after the December 2012 restriction was signed, and published a corresponding document.[135] His press secretary Anna Veduta declared, "the Investigating Committee is arranging propaganda soil to put Alexei under a home arrest".[135]

The case

In December 2007, Alexei Navalny and his brother Oleg created a Cyprian offshore firm Alortag Management Limited, headed by Maria Zaprudskaya. On 19 May 2008, Glavpodpiska agency was registered, with 99% of its charter capital belonging to Alortag Management Limited, and 1% belonging to the then-Glavpodpiska CEO, Maria's father Leonid Zaprudsky. Oleg Navalny knew Post of Russia commonly breaks terms of matter, and made an offer to one of its largest clients, Yves Rocher Vostok, the Eastern European subsidiary of Yves Rocher between 2008 and 2012, to accredit Glavpodpiska with the job. On 5 August 2008, the parties signed a contract. Their relationships lasted over three years, with both parties having had no complaints to the other. To fulfill the obligations under the agreement, Glavpodpiska outsourced the task to a sub-supplier, AvtoSAGA. Glavpodpiska also signed a contract with the Multiprofile Processing Company in 2008, according to which, the latter, in particular, processed and delivered the bills to Rostelekom clients. It also filed no complaints to Glavpodpiska. In November and December 2012, the Investigating Committee interrogated and questioned Yves Rocher Vostok. On 10 December, Bruno Leproux, general director of Yves Rocher Vostok, filed to the Investigative Committee, asking to investigate if the Glavpodpiska subscription company had damaged Yves Rocher Vostok, and the Investigative Committee initiated a case.[136]

The prosecution claimed they had embezzled over 26.7 million rubles ($540,000) from Yves Rocher Vostok, and 4.4 million rubles from the Multiprofile Processing Company. These funds were subsequently legalized by transferring them on fictitious grounds from a fly-by-night company to Kobyakovskaya Fabrika Po Lozopleteniyu, a willow weaving company, founded by Navalny and operated by his parents, according the Russian Investigative Committee. According to the investigation data, Oleg Navalny, a deputy director of a branch of Russian Post and of the Express Mail Service, persuaded Yves Rocher Vostok to conclude a contract for postal services with the company Glavpodpiska created by Alexei Navalny. Supposedly, the latter company did not render any transportation services and could not render them, entrusting them to another company managed by a friend of Oleg, and the services rendered by this company cost much less. The surplus was considered as businesslike customary commission income. A similar scheme is claimed to be found in the case on the Russian Interregional Processing Company: In 2008, Oleg Navalny is said to have persuaded the company to conclude contracts with his company concerning services of transportation of receipts, forms, and other printed products. Prices for services are seen as excessive, resulting in damages to the company in the amount of 3.8 million rubles.[137][138][139]

Both brothers denied the charges, and Yves Rocher denied that they had any losses.

Home arrest and limitations

On 28 February 2014, Navalny was placed under house arrest and prohibited from communicating with anyone other than his family, after allegedly violating travel restrictions.[12][140] On 13 March, his LiveJournal blog was blocked in Russia, because "functioning of the given web page breaks the regulation of the juridical decision of the bail hearing of a citizen, against who a criminal case has been initiated".[141]

Conviction

The sentence was scheduled originally to be read on 15 January 2015, but on 29 December 2014 the judge suddenly announced that she was to read the sentence on 30 December. Alexei Navalny was given 3.5 years of suspended sentence, whereas Oleg Navalny was sentenced to 3.5 years in prison and was arrested after the sentence was read.[142]

In the evening, several thousands protesters gathered in the center of Moscow. Navalny broke his home arrest to attend the rally. He was immediately arrested by the police and brought back home.[143] Subsequently, the court refused to arrest Navalny, since the sentence had already been read.[144]

Reactions

The charges against Navalny and his brother are largely seen as a tactic by Putin to silence the opposition in Russia.[145] The spokeswoman for EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini stated the same day that the sentence was likely to be politically motivated.[143] Navalny made a statement, "The government is not just trying to jail its political opponents ... this time, they are destroying and torturing the families of the people who oppose them".[12]

Participation in the pro-democracy coalition

On 27 January 2015, Navalny declared the main means to pressure the current power would be street activism and announced a march to be held in Moscow on 1 March. The manifesto of the march demanded non-participation of Russia in the war in Donbass as well as social security during the upstarting decline in the Russian economy.[146] Soon thereafter, it was declared the march would take place not only in Moscow, but also in many other Russian cities.[147] On 15 February, he was arrested as he was campaigning in Moscow Metro, promoting the march and giving out leaflets,[148] and soon thereafter, a court ordered Navalny should be arrested for 15 days, effectively leaving him no possibility to attend the march.[149]

On 27 February, one of the two remaining RPR-PARNAS co-chairmen Boris Nemtsov was shot dead. This eventually led to the plan change: the organizers demanded the march, which was planned to take place in the residential district of Maryino in the outskirts of the city, be replaced with a mourning march and should take place in the very center, to which the city hall agreed,[150] although it was originally stated that would be impossible because that would break a law.[151] Navalny pleaded to be given an opportunity to attend the funeral, but the court rejected the plea.[152] On his release, Navalny said the murder would not affect his opposition activities.[153]

On 10 April, Saint Petersburg regional divisions of Progress Party and RPR-PARNAS wrote a letter to their chairmen, Navalny and Mikhail Kasyanov, stating the parties would effectively spoil each other's chances during the upcoming elections and suggesting the parties should unify and become a single one.[154] On the next day, the parties' central committees declared this would be considered,[155] and in a few days, Navalny declared a wide discussion had taken place among these and other closely aligned parties, and resulted in an agreement of formation of a new electoral bloc between the two leaders.[156] Soon thereafter, it was signed by four other parties and supported by Khodorkovsky's Open Russia foundation.[157] Electoral blocs are not present within the current law system of Russia, so it would be realized via the means of a single party, RPR-PARNAS, which is not only eligible for participation in the statewide elections, but is also currently not required to collect citizens' signatures for the right to participate in the State Duma elections scheduled for December 2016 thanks to the regional parliament mandate the party holds, previously taken by Nemtsov.[158]

Russian nationalism

Alexei Navalny stated in 2011 that he considers himself a "nationalist democrat".[159] International media have often commented on his ambiguous but non-condemnatory stance toward ethnic Russian nationalism.[160][161] The BBC noted in a profile of Navalny that his endorsement of a political campaign called "Stop Feeding the Caucasus" and his willingness to speak at ultra-nationalist events "have caused concern among liberals". He also has been a co-organizer of the "Russian March",[162] which Radio Free Europe describes as "a parade uniting Russian nationalist groups of all stripes",[163] and has appeared as a speaker alongside Russian nationalists.[164]

Navalny is agitating on behalf of aggressive anti-immigration policies.[165]

Navalny once compared dark-skinned Caucasus militants with cockroaches and made a video about it.[166] "Cockroaches can be killed with a slipper, but as for humans, I recommend a pistol."[167][168] Navalny's defenders suggested the comment was simply a joke. It has also been debated whether or not Navalny's ethnic nationalism is a populist strategy or arises from his real convictions.[169]

Early in 2012 Navalny stated on Ukrainian TV, "Russian foreign policy should be maximally directed at integration with Ukraine and Belarus… In fact, we are one nation. We should enhance integration."[170] During the same broadcast Navalny said that he did not intend "to prove that the Ukrainian nation does not exist. God willing, it does". He added, "No one wants to make an attempt to limit Ukraine's sovereignty".[170][171] In October 2014 Navalny stated "I do not see any kind of difference at all between Russians and Ukrainians", he admitted that his views might provoke "horrible indignation" in Ukraine.[172] He also said that Russian government should stop "sponsoring the war" in Donbass.[172] Navalny have strongly criticized Vladimir Putin's policies in Ukraine: "Putin likes to speak about the 'Russian world' but he is actually making it smaller. In Belarus, they sing anti-Putin songs at football stadiums; in Ukraine they simply hate us. In Ukraine now, there are no politicians who don’t have extreme anti-Russian positions. Being anti-Russian is the key to success now in Ukraine, and that is our fault".[173]

In March 2014, Navalny declared that he did not support Russia's annexation of Crimea. According to The Moscow Times, "Navalny suggested that Kiev should grant Crimea greater autonomy while remaining part of Ukraine, guarantee the right to speak Russian in Ukraine, keep Ukraine out of NATO, and let the Russian Black Sea fleet remain in the peninsula free of charge".[174] In October 2014 Navalny stated in an interview by Ekho Moskvy that he would not return Crimea to Ukraine if he were to become the president of Russia but that "a normal referendum" should be held in Crimea to decide what country the peninsula belongs to.[172]

Family

Navalny is married and has two children.[44]

Awards and honors

Navalny was named "Person of the Year 2009" by Russian business newspaper Vedomosti.[175]

Navalny was a World Fellow at Yale University's World Fellows Program, aimed at "creating a global network of emerging leaders and to broaden international understanding" in 2010.[176]

In 2011, Foreign Policy magazine named Navalny to the FP Top 100 Global Thinkers, along with Daniel Domscheit-Berg and Sami Ben Gharbia of Tunisia, for "shaping the new world of government transparency".[177] FP picked him again in 2012.[178] He was listed by Time magazine in 2012 as one of the world's 100 most influential people, the only Russian on the list.[179] In 2013, Navalny came in at No. 48 among "world thinkers" in an online poll by the UK magazine Prospect.[180]

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to the exchange rates[98] set by the Central Bank of Russia for 8 September 2013.

References

- ↑ Carl Schreck (9 March 2010). "Russia's Erin Brockovich: Taking On Corporate Greed". Time. Archived from the original on 14 February 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ↑ Matthew Kaminski (3 March 2012). "The Man Vladimir Putin Fears Most (the weekend interview)". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "Russian blogger Alexei Navalny in spotlight after arrest". Washington Post.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Englund, Will (9 September 2013). "Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny has strong showing in Moscow mayoral race, despite loss". The Washington Post.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Tom Parfitt (10 May 2011). "Russian blogger Alexei Navalny faces criminal investigation". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Russian opposition leader Navalny faces third inquiry". BBC News. 24 December 2012. Archived from the original on 17 April 2013., BBC, 24 December 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Brumfield, Ben; Phil Black (18 July 2013). "Report: Stark Putin critic Navalny hit with criminal conviction". CNN. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ David M. Herszenhorn (18 July 2013) "Russian Court Convicts Opposition Leader". New York Times

- ↑ "Радио ЭХО Москвы :: Новости / Правозащитный центр Мемориал признал Алексея Навального политическим заключенным". Echo.msk.ru. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press. "Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny has been released from custody 1 day after sentencing". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Andrew E. Kramer (16 October 2013) Navalny Is Spared Prison Term in Russia. New York Times.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Vasilyeva, Nataliya (30 December 2014). "Conviction of Putin foe sets off protest in Moscow". Associated Press. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Sergei Hrabovsky. Олексій Навальний як дзеркало російської революції (in Ukrainian). day.kiev.ua. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ АЛЕКСЕЙ НАВАЛЬНЫЙ (in Russian). esquire.ru. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "Alexei Navalny". The Moscow Times. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Guy Faulconbridge (11 December 2011). "Newsmaker – Protests pitch Russian blogger against Putin". Reuters. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "Navalny, Alexey Anatolich" (in Russian). Kommersant. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ↑ "About Navalny" (in Russian). navalny.ru. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ↑ "SvobodaNews.ru Московское "Яблоко" поддержало проведение "Русского марша" deadurl=no". Argued as following: "It is clearly stated in the preamble of our declaration that the Yabloko Party thoroughly and sharply opposes any national and racial discord and any xenophobia. However in this case, when we know... that the Constitution guarantees to us the right to gather peacefully and without a weapon, we see that in these conditions the prohibition of the Russian March as it was announced, provokes the organizers to some activities which could end not so good. Thus we appeal to the Moscow city administration... for permission..."

- ↑ "Human rights activist protests far-right march in Moscow". En.rian.ru. 17 October 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Russian chief rabbi supports ban on November 4 March". Interfax-religion.com. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "РИА Новости – Справки – "Русский марш". События прошлого года". Rian.ru. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Navalny, Alexey". Lenta.ru. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ↑ Ilya Azarov (15 December 2007). "Яблоко" откатилось (in Russian). Gazeta.ru. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ↑ Nataliya Vasilyeva (1 April 2010). "Activist presses Russian corporations for openness". Seattle Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Выборы мэра Москвы. Gazeta.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ↑ Как пилят в Транснефти (in Russian). LiveJournal. Archived from the original on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ↑ "Russia checks claims of $4bn oil pipeline scam". BBC News. 17 November 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ↑ Soldatkin, Vladimir (14 January 2011). "Russia's Transneft denies $4 bln theft". Reuters. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Alexey Navalny (29 December 2010). "RosPil". Navalny Live Journal Blog (in Russian deadurl=no). Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Catherine Belton (10 May 2011). "Russia Targets Anti-Graft Blogger". The Financial Times. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Alexander Bratersky (11 May 2011). "Navalny Targeted in Fraud Inquiry". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Daniel Sandford (30 November 2011). "Russians tire of corruption spectacle". BBC News. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Alexey Navalny (30 May 2011). "RosYama" (in Russian). Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ↑ Bálint Ablonczy (23 July 2012). "It's ugly, but it was ours". Hetivalasz. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Инновационные технологии: как это работает на самом деле (in Russian). Navalny.Live Journal. 3 August 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Andy Potts (21 February 2011). "Vekselberg faces questions over Hungarian property fraud". The Moscow News. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "Hungary: detentions linked to the sale of property in Moscow". OSW. 16 February 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Julia Ioffe (5 December 2011). "Russian Elections: Faking It". The New Yorker. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Julia Ioffe (6 December 2011). "Putin's Big Mistake?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Tom Parfitt (17 December 2011). "Vladimir Putin's persecution campaign targets protest couple". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "The Blog on Navalny in English". LiveJournal. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ↑ Miriam Elder (7 December 2011). "Medvedev 'tweet' sends the Russian blogosphere into a frenzy". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Stephen Ennis (21 December 2011). "Profile: Russian blogger Alexei Navalny". BBC News. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Guy Faulconbridge (20 December 2011). "Navalny challenges Putin after leaving Russian jail". Reuters. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Fred Weir (24 December 2011). "Huge protest demanding fair Russian elections hits Moscow". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "Russia election: Police arrest 550 at city protests". BBC News. 5 March 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "Police keep anti-Putin protesters on the run". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. 8 May 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "Amnesty Calls Navalny, Udaltsov 'Prisoners of Conscience'". Radio Free Europe. 18 May 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ "Homes of Russian opposition figures searched ahead of rally deadurl=no".. RT.com. 11 June 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Charles Clover (26 July 2012). "Blogger strikes at Putin with data release". Financial Times. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 52.5 Andrew E. Kramer (30 March 2012). "Activist Presses for Inquiry into Senior Putin Deputy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "Russian whistleblower accuses Putin's investment czar of multimillion dollar corruption". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 30 March 2012. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ↑ "Navalny Must Pay for 'Crooks and Thieves' Comment deadurl=no". The Moscow Times. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 "Russian blogger Navalny charged with embezzlement". BBC News. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 "Putin critic Navalny charged with theft". Al Jazeera. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "An Analysis of the Russian Federation's prosecutions of Alexei Navalny". Docs.google.com. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Daniel Sandford (17 April 2013). "BBC News – Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny goes on trial". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Elder, Miriam (18 July 2013). "Russia: Alexei Navalny found guilty of embezzlement". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "Outspoken Putin critic Alexei Navalny hit with prison sentence". CNN. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ Воронин, Николай (18 July 2013). Как судили Навального: репортаж из зала суда (in Russian). BBC. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 62.4 62.5 "Reaction to Russia's Jailing of Alexei Navalny". Wall Street Journal. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "Mikhail Gorbachev reacts to the sentencing of Alexey Navalny". The Gorbachev Foundation. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Herszenhorn, David M. (18 July 2013). "Russian Court Convicts Opposition Leader". New York Times. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "Navalny verdict is a warning to the fifth column". Pravda. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "On the Conviction and Sentencing of Alexey Navalniy and Pyotr Ofitserov". U.S. State Department. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "Statement by the Spokesperson of High Representative Catherine Ashton on the sentencing of Alexey Navalny and Pyotr Ofitserov" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "Alexei Navalny freed following anti-Putin protests in Moscow – video". The Guardian (London). 19 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ "Alexei Navalny Freed Pending Appeal". Wall Street Journal. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Maria Tsvetkova and Gleb Bryanski (27 October 2012). "Russia activists detained after opposition council meets". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ↑ "Anti-Kremlin Figure Navalny Sets Sights on Presidency". RIA Novosti. 5 April 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ "Opposition blogger Navalny voices presidential ambitions amid dwindling support". RT. 5 April 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ Volkov, Dennis (5 April 2013). "Analysis of Navalny's Ratings". Levada Center. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ Stepan Kravchenko (5 April 2013). "Putin, Allies Threatened With Jail as Navalny to Seek Presidency". Bloomberg. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ http://www.gazeta.ru/news/lastnews/2011/12/22/n_2143786.shtml

- ↑ http://www.rg.ru/2012/06/01/zakon-anons.html

- ↑ http://www.gazeta.ru/politics/news/2013/02/14/n_2754021.shtml

- ↑ http://www.echo.msk.ru/news/1022210-echo.html

- ↑ http://www.mn.ru/moscow_authority/20130530/347635870.html

- ↑ http://ria.ru/politics/20130604/941316905.html

- ↑ http://ria.ru/politics/20130606/941917281.html

- ↑ http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2206494

- ↑ http://lenta.ru/news/2013/06/03/willing/

- ↑ http://navalny.livejournal.com/812133.html

- ↑ http://tvrain.ru/teleshow/here_and_now/eto_rejderskij_zahvat_partii_pochemu_ryzhkov_ushel_iz_rpr_parnas-362272/

- ↑ http://lenta.ru/news/2013/07/09/signatures/

- ↑ Smolchenko, Anna (17 July 2013). "Navalny Moscow mayoral bid accepted ahead of verdict". Fox News. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "Navalny pulls out of Moscow poll, calls for boycott". Agence France-Presse.

- ↑ http://ria.ru/incidents/20130719/950774598.html

- ↑ "Freed Kremlin critic arrives in Moscow". Al-Jazeera.

- ↑ http://www.comcon-2.ru/default.asp?artID=2870

- ↑ http://www.comcon-2.ru/default.asp?artID=2868

- ↑ http://www.comcon-2.ru/default.asp?artID=2861

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 http://www.comcon-2.ru/default.asp?artID=2856

- ↑ http://www.comcon-2.ru/default.asp?artID=2846

- ↑ http://www.comcon-2.ru/default.asp?artID=2845

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 http://www.comcon-2.ru/default.asp?artID=2841

- ↑ http://www.cbr.ru/currency_base/daily.aspx?date_req=08.09.2013

- ↑ http://report.navalny.ru/media/navalny_report.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-23970618

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Laura Mills and Lynn Berry (8 September 2013). "Strong Showing for Navalny in Moscow Mayoral Race". Associated Press.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 http://www.ng.ru/itog/2013-12-30/1_navalny.html

- ↑ http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/alexey-navalnys-miraculous-doomed-campaign

- ↑ https://navalny.livejournal.com/825324.html

- ↑ https://navalny.livejournal.com/839695.html

- ↑ https://navalny.livejournal.com/822041.html

- ↑ http://navalny.livejournal.com/822868.html

- ↑ https://navalny.livejournal.com/829626.html

- ↑ https://navalny.livejournal.com/835240.html

- ↑ http://www.themoscowtimes.com/news/article/navalny-wants-sobyanin-his-elder-daughter-checked-for-corruption/484535.html

- ↑ http://www.themoscowtimes.com/news/article/navalny-wants-sobyanin-his-elder-daughter-checked-for-corruption/484535.html

- ↑ https://navalny.livejournal.com/840474.html

- ↑ http://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/articles/2013/08/20/mosgorizbirkom-pokazal-dokument-o-prave-sobyanina

- ↑ http://lenta.ru/news/2013/08/21/navalnytrash/

- ↑ http://lenta.ru/news/2013/08/21/montenegro/

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 http://lenta.ru/news/2013/09/26/chern/

- ↑ https://navalny.livejournal.com/848063.html

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 118.2 http://www.gazeta.ru/politics/2013/09/09_a_5645357.shtml

- ↑ http://www.moscow_city.vybory.izbirkom.ru/region/region/moscow_city?action=show&root=1&tvd=27720001368293&vrn=27720001368289®ion=77&global=&sub_region=0&prver=0&pronetvd=null&vibid=27720001368293&type=222

- ↑ https://navalny.livejournal.com/856833.html

- ↑ http://navalny.livejournal.com/856002.html

- ↑ http://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/articles/2013/09/09/na-bolotnoj-ploschadi-nachinaetsya-miting-v-podderzhku

- ↑ https://navalny.livejournal.com/856833.html

- ↑ http://navalny.livejournal.com/857956.html

- ↑ https://navalny.livejournal.com/862379.html

- ↑ http://navalny.livejournal.com/871356.html

- ↑ http://www.ng.ru/itog/2013-12-30/1_navalny.html

- ↑ http://slon.ru/russia/navalnyy_budet_pretendentom_na_vtoroe_mesto_v_prezidentskoy_gonke-1028486.xhtml

- ↑ Svolik, Milan (12 October 2013). "The best way to demoralize the opposition in Russia? Beat them in a fair election". Washington Post. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ↑ http://www.newrepublic.com/article/113929/aleksei-navalny-trial-blogger-gets-five-years-jail#

- ↑ http://www.mk.ru/politics/russia/news/2013/09/30/923229-peskov-putin-ne-proiznosit-imeni-navalnogo-chtobyi-ne-delat-ego-populyarnee.html

- ↑ http://lenta.ru/news/2012/12/17/navalny/

- ↑ http://www.vz.ru/news/2014/1/13/667664.html

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 http://www.bbc.co.uk/russian/russia/2014/01/140113_navalny_travel_restrictions

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/russian/russia/2014/12/141229_navalny_yves_rocher_background

- ↑ http://www.russia-ic.com/society_politics/politics/2605/#.VKbt-CvF-_Q

- ↑ http://rbth.co.uk/news/2014/12/30/russian_opposition_activist_navalny_gets_suspended_sentence_in_yves_roch_42658.html

- ↑ http://rapsinews.com/judicial_news/20131115/269672881.html

- ↑ "Court puts Russian opposition leader under house arrest". Moscow News.Net. 28 February 2014.

- ↑ http://www.gazeta.ru/politics/news/2014/03/13/n_6010813.shtml

- ↑ Smith-Spark, Laura; Chance, Matthew; Eshchenko, Alla (30 December 2014). "Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny gets 3.5-year suspended sentence". CNN. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 Alexander, Harriet (30 December 2014). "Alexei Navalny breaks his house arrest to attend protest against his sentence". The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ Замоскворецкий суд Москвы вернул Федеральной службе исполнения наказаний материал о нарушении Алексеем Навальным домашнего ареста (in Russian). Echo of Moscow. 31 December 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Вендик, Юри (30 December 2014). Олег Навальный приговорён к 3,5 годам по делу "Ив Роше" (in Russian). BBC Russian. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ https://navalny.com/p/4089/

- ↑ https://navalny.com/p/4119/

- ↑ https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2668678

- ↑ https://top.rbc.ru/politics/19/02/2015/54e5fe669a79472ab7a62130

- ↑ https://www.novayagazeta.ru/news/1692000.html

- ↑ https://www.novayagazeta.ru/news/1691994.html

- ↑ https://top.rbc.ru/politics/02/03/2015/54f44a9c9a7947d0ed945976

- ↑ https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-31762173

- ↑ https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2707188

- ↑ https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2707439

- ↑ https://navalny.com/p/4206/

- ↑ https://navalny.com/p/4207/

- ↑ https://www.echo.msk.ru/programs/razvorot/1532392-echo/

- ↑ The birth of Russian citizenry, The Economist, 2011

- ↑ Did Russian Opposition Leader Alexey Navalny Just Endorse A Race Riot?, by Mark Adomanis, Forbes, 15 July 2013

- ↑ So where’s the change in Russia?, by Jean Radvanyi, Le Monde Diplomatique, April 2012

- ↑ "В столице отрепетировали "Русский марш"".

- ↑ Russia's Aleksei Navalny: Hope Of The Nation – Or The Nationalists?, by Robert Coalson, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 28 July 2013

- ↑ Ellen Barry (9 December 2011) Rousing Russia With a Phrase. New York TImes

- ↑ Mark Adomanis (4 August 2014). "3 Things Barack Obama Got Wrong About Russia". Forbes.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oVNJiO10SWw

- ↑ Barry, Ellen (9 December 2011). "Rousing Russia With a Phrase". New York Times.

- ↑ Hitchens, Peter (25 February 2012). "If not Putin, who? It's because I love my own country that I can see the point of this sinister tyrant who so ruthlessly stands up for Russia". Daily Mail (London).

- ↑ Popescu, N. (2012). "The Strange Alliance of Democrats and Nationalists". Journal of Democracy 23 (3): 46. doi:10.1353/jod.2012.0046.

- ↑ Navalny: Integration with Belarus – Main Task for Russia. Telegraf.by]. 13 February 2012

- ↑ 172.0 172.1 172.2 Anna Dolgov (16 October 2014) "Navalny Wouldn't Return Crimea, Considers Immigration Bigger Issue Than Ukraine | News". The Moscow Times.

- ↑ "‘Putin is destroying Russia. Why base his regime on corruption?’ asks Navalny ". The Guardian. 17 October 2014.

- ↑ "Navalny Defies House Arrest Terms in Online Condemnation of Russia's Actions in Ukraine". The Moscow Times. 21 March 2014.

- ↑ Персоны года – 2009: Частное лицо года. Vedomosti (in Russian). 30 December 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ↑ "The World Fellows: Alexey Navalny". Yale University. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ↑ "The FP Top 100 Global Thinkers". Foreign Policy. December 2011. Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ "The FP Top 100 Global Thinkers". Foreign Policy. 28 November 2012. Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ Garry Kasparov (18 April 2012). "Alexei Navalny". Time. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ "The results of Prospect's world thinkers poll". Prospect. April 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alexey Navalny. |

| Wikinews has related news: Russia's main airport faces high danger from dump birds |

- Navalny's site (Russian)

- Navalny's blog (Russian)

- Navalny's page for the Yale World Fellows Program

- Navalny's blog translated to English, since 6-Dec-2011

- His project to fight corruption (Russian)

- Articles

- Navalny biography (Russian)

- Navalny biography in photographs (Russian)

- Reactions to Navalny's sentence (Russian)

- The Guardian

- The Telegraph

- The Washington Post

- The Wall Street Journal