Alexander Scriabin

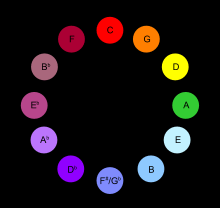

Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin[1] (English pronunciation: /skriˈɑːbɪn/;[2] Russian: Алекса́ндр Никола́евич Скря́бин, Russian pronunciation: [ɐlʲɪˈksandr nʲɪkəˈlaɪvʲɪtɕ ˈskrʲæbʲɪn]; 6 January 1872 [O.S. 25 December 1871] – 27 April [O.S. 14 April] 1915)[3] was a Russian composer and pianist. Scriabin, who was influenced by Frédéric Chopin,[4] composed early works that are characterised by tonal language. Later in his career, independently of Arnold Schoenberg, Scriabin developed a substantially atonal and much more dissonant musical system, which accorded with his personal brand of mysticism. Scriabin was influenced by synesthesia, and associated colors with the various harmonic tones of his atonal scale, while his color-coded circle of fifths was also influenced by theosophy. He is considered by some to be the main Russian Symbolist composer.

Scriabin was one of the most innovative and most controversial of early modern composers. The Great Soviet Encyclopedia said of Scriabin that, "No composer has had more scorn heaped on him or greater love bestowed." Leo Tolstoy described Scriabin's music as "a sincere expression of genius."[5] Scriabin had a major impact on the music world over time, and influenced composers such as Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev,[6] and Nikolai Roslavets. However Scriabin's importance in the Soviet musical scene, and internationally, drastically declined. According to his biographer, "No one was more famous during their lifetime, and few were more quickly ignored after death."[7] Nevertheless, his musical aesthetics have been reevaluated, and his ten published sonatas for piano, which arguably provided the most consistent contribution to the genre since the time of Beethoven's set, have been increasingly championed.[8]

Biography

Childhood and education (1872–1893)

Scriabin was born into an aristocratic family in Moscow on Christmas Day 1871, according to the Julian Calendar (this translates to 6 January 1872 in the Gregorian Calendar). His father and all of his uncles had military careers.[7] When he was only a year old, his mother—herself a concert pianist and former pupil of Theodor Leschetizky—died of tuberculosis.

After her death, Scriabin's father completed tuition in the Turkish language in St Petersburg, subsequently becoming a diplomat and finally leaving for Turkey, leaving the infant Sasha (as he was known) with his grandmother, great aunt, and aunt. Scriabin's father would later remarry, giving Scriabin a number of half-brothers and sisters. His aunt Lyubov (his father's unmarried sister) was an amateur pianist who documented Sasha's early life until the time he met his first wife. As a child, Scriabin was frequently exposed to piano playing, and anecdotal references describe him demanding that his aunt play for him.

Apparently precocious, Scriabin began building pianos after being fascinated with piano mechanisms. He sometimes gave away pianos he had built to house guests. Lyubov portrays Scriabin as very shy and unsociable with his peers, but appreciative of adult attention. Another anecdote tells of Scriabin trying to conduct an orchestra composed of local children, an attempt that ended in frustration and tears. He would perform his own amateur plays and operas with puppets to willing audiences. He studied the piano from an early age, taking lessons with Nikolai Zverev, a strict disciplinarian, who was teaching Sergei Rachmaninoff and a number of other prodigies at the same time, though Scriabin was not a pensionaire like Rachmaninoff.[7]

In 1882 he enlisted in the Second Moscow Cadet Corps. As a student, he became friends with the actor Leonid Limontov, although in his memoirs Limontov recalls his reluctance to become friends with Scriabin, who was the smallest and weakest among all the boys and was sometimes teased because of this.[7] However, Scriabin won his peers' approval at a concert in which he played the piano.[7] He ranked generally first in his class academically, but was exempt from drilling due to his physique and was given time each day to practise at the piano.

Scriabin later studied at the Moscow Conservatory with Anton Arensky, Sergei Taneyev, and Vasily Safonov. He became a noted pianist despite his small hands, which could barely stretch to a ninth. Feeling challenged by Josef Lhévinne, he damaged his right hand while practicing Franz Liszt's Réminiscences de Don Juan and Mily Balakirev's Islamey.[9] His doctor said he would never recover, and he wrote his first large-scale masterpiece, his Piano Sonata No. 1 in F minor, as a "cry against God, against fate." It was his third sonata to be written, but the first to which he gave an opus number (his second was condensed and released as the Allegro Appassionato, Op. 4). He eventually regained the use of his hand.[9]

In 1892 he graduated with the Little Gold Medal in piano performance, but did not complete a composition degree because of strong differences in personality and musical opinion with Arensky (whose faculty signature is the only one absent from Scriabin's graduation certificate) and an unwillingness to compose pieces in forms that did not interest him.[7]

Early career (1894–1903)

In 1894 Scriabin made his debut as a pianist in St. Petersburg, performing his own works to positive reviews. During the same year, Mitrofan Belyayev agreed to pay Scriabin to compose for his publishing company (he published works by notable composers such as Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov).[7] In August 1897, Scriabin married the young pianist Vera Ivanovna Isakovich, and then toured in Russia and abroad, culminating in a successful 1898 concert in Paris. That year he became a teacher at the Moscow Conservatory, and began to establish his reputation as a composer. During this period he composed his cycle of études, Op. 8, several sets of preludes, his first three piano sonatas, and his only piano concerto, among other works, mostly for piano.

For a period of five years, Scriabin was based in Moscow, during which time the first two of his symphonies were conducted by his old teacher Safonov.

According to later reports, between 1901 and 1903 Scriabin envisioned writing an opera. He talked a lot about it and expounded its ideas in the course of normal conversation. The work would center around a nameless hero, a philosopher-musician-poet. Among other things, he would declare: I am the apotheosis of world creation. I am the aim of aims, the end of ends.[7] The Poem Op. 32 No. 2 and the Poème Tragique Op. 34 were originally conceived as arias in the opera.[10]

Leaving Russia (1903–09)

By the winter of 1904, Scriabin and his wife had relocated to Switzerland, where he began work on the composition of his Symphony No. 3. While living in Switzerland, Scriabin was separated legally from his wife, with whom he had had four children. The work was performed in Paris during 1905, where Scriabin was now accompanied by Tatiana Fyodorovna Schloezer—a former pupil and the niece of Paul de Schlözer.[7] With Schloezer, he had other children, including a son named Julian Scriabin, who composed several musical works before drowning in the Dnieper River at Kiev in 1919 at the age of 11.[11]

With the financial assistance of a wealthy sponsor, he spent several years traveling in Switzerland, Italy, France, Belgium and the United States, working on more orchestral pieces, including several symphonies. He was also beginning to compose "poems" for the piano, a form with which he is particularly associated. While in New York City in 1907 he became acquainted with the Canadian composer Alfred La Liberté, who went on to become a personal friend and disciple.[12]

In 1907 he settled in Paris with his family and was involved with a series of concerts organized by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, who was actively promoting Russian music in the West at the time. He relocated subsequently to Brussels (rue de la Réforme 45) with his family.

Return to Russia (1909–14)

In 1909 he returned to Russia permanently, where he continued to compose, working on increasingly grandiose projects. For some time before his death he had planned a multi-media work to be performed in the Himalaya Mountains, that would cause a so-called "armageddon," "a grandiose religious synthesis of all arts which would herald the birth of a new world."[13] Scriabin left only sketches for this piece, Mysterium, although a preliminary part, named L'acte préalable ("Preparatory Action") was eventually made into a performable version by Alexander Nemtin.[14] Part of that unfinished composition was performed with the title 'Prefatory Action' by Vladimir Ashkenazy in Berlin with Aleksei Lyubimov at the piano.[15] Several late pieces published during the composer's lifetime are believed to have been intended for Mysterium, like the Two Dances Op. 73.[16]

Scriabin was small and reportedly frail throughout his life. In 1915, at the age of 43, he died in Moscow from septicemia as a result of a sore on his upper lip. He had mentioned the sore as early as 1914 while in London.[17]

Music

|

"Étude Op. 8 No. 12"

Awadagin Pratt performs Alexander Scriabin's Étude, Op. 8, No. 12 at the White House Classical Music Student Workshop Concert. (2009-11-04) Étude Op. 8 No. 12

Étude, Op. 8, No. 12. played by Domenico Stigliani |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Rather than seeking musical versatility, Scriabin was happy to write almost exclusively for solo piano and for orchestra.[18] His earliest piano pieces resemble Frédéric Chopin's and include music in many genres that Chopin himself employed, such as the étude, the prelude, the nocturne, and the mazurka. Scriabin's music progressively evolved over the course of his life, although the evolution was very rapid and especially brief when compared to most composers. Aside from his earliest pieces, the mid- and late-period pieces use very unusual harmonies and textures.

The development of Scriabin's style can be traced in his ten piano sonatas: the earliest are composed in a fairly conventional late-Romantic manner and reveal the influence of Chopin and sometimes Franz Liszt, but the later ones are very different, the last five being written without a key signature. Many passages in them can be said to be atonal, though from 1903 through 1908, "tonal unity was almost imperceptibly replaced by harmonic unity."[19]

First period (1880s–1903)

Scriabin's first period is usually described as going from his earliest pieces up to his Second Symphony Op. 29. The works from the first period adhere to the romantic tradition, thus employing the common practice period harmonic language. However, Scriabin's voice is present from the very beginning, in this case by his fondness of the dominant function[20] and added tone chords.[21]

Scriabin's early harmonic language was specially fond of the thirteenth dominant chord, usually with the 7th, 3rd, and 13th spelled in fourths.[22] This voicing can also be seen in several of Chopin's works.[22] According to Peter Sabbagh, this voicing would be the main generating source of the later Mystic chord.[21] More importantly, Scriabin was fond of simultaneously combining two or more of the different dominant seventh enhancings, like 9ths, altered 5ths, and raised 11ths. However, despite these tendencies, slightly more dissonant than usual for the time, all these dominant chords were treated according to the traditional rules: the added tones resolved to the corresponding adjacent notes, and the whole chord was treated as a dominant, fitting inside tonality and diatonic, functional harmony.[21]

.png)

Second period (1903–07)

This period begins with Scriabin's Fourth Piano Sonata Op. 30, and ends around his Fifth Sonata Op. 53 and the Poem of Ecstasy Op. 54, which are considered transitional works. During this period, Scriabin's music becomes more chromatic and dissonant, yet still mostly adhering to traditional functional tonality. As dominant chords are more and more extended, they gradually lose their dominant function. Scriabin wanted his music to have a radiant, shining feeling to it, and achieved this by raising a greater number of chord tones. During this time, complex forms like the mystic chord are hinted, but still show their roots as Chopin-like harmony.[21]

At first, the added dissonances are resolved conventionally according to voice leading, but the focus slowly shifts towards a system in which chord coloring is most important. Later on, fewer dissonances on the dominant chords are resolved. According to Sabbanagh, "the dissonances are frozen, solidified in a color-like effect in the chord"; the added notes become part of it.[21]

Third period (1907–15)

I decided that the more higher tones there are in harmony, it would turn out to be more radiant, sharper and more brilliant. But it was necessary to organize the notes giving them a logical arrangement. Therefore, I took the usual thirteenth-chord, which is arranged in thirds. But it is not that important to accumulate high tones. To make it shining, conveying the idea of light, a greater number of tones had to be raised in the chord. And, therefore, I raise the tones: At first I take the shining major third, then I also raise the fifth, and the eleventh—thus forming my chord—which is raised completely and, therefore, really shining.[23][24]

[About the Mystic chord:] "This is not a dominant chord, but a basic chord, a consonance. It is true—it sounds soft, like a consonance."[25][26]

"In former times the chords were arranged by thirds or, which is the same, by sixths. But I decided to construct them by fourths or, which is the same, by fifths."[21][27]

After those transitional works, Scriabin's third period is considered to begin with either the Album Leaf Op. 58[28] or the Two Poems Op. 55.

According to Samson, while the sonata-form of Scriabin's Sonata No. 5 has some meaning to the work's tonal structure, in his Sonata No. 6 and Sonata No. 7 formal tensions are created by the absence of harmonic contrast and "between the cumulative momentum of the music, usually achieved by textural rather than harmonic means, and the formal constraints of the tripartite mould". He also argues that the Poem of Ecstasy and Vers la flamme "find a much happier co-operation of 'form' and 'content'" and that later sonatas, such as No. 9, employ a more flexible sonata-form.[19]

According to Claude Herdon, in Scriabin's late music "tonality has been attenuated to the point of virtual extinction, although dominant sevenths, which are among the strongest indicators of tonality, preponderate. The progression of their roots in minor thirds or diminished fifths [...] dissipate the suggested tonality."[29]

Varvara Dernova argues that "The tonic continued to exist, and, if necessary, the composer could employ it [...] but in the great majority of cases, he preferred the concept of a tonic in distant prespective, so to speak, rather than the actually sounding tonic [...] The relationship of the tonic and dominant functions in Scriabin's work is changed radically; for the dominant actually appears and has a varied structure, while the tonic exists only as if in the imagination of the composer, the performer, and the listener."[30]

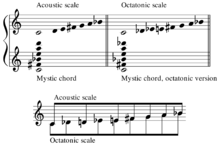

Most of the music of this period is built on the acoustic and octatonic scales, as well as the nine-note scale resulting from their combination.[28]

Philosophical influences and influence of colour

Scriabin was interested in Friedrich Nietzsche's Übermensch theory, and later became interested in theosophy. Both would influence his music and musical thought. During 1909–10 he lived in Brussels, becoming interested in Jean Delville's Theosophist philosophy and continuing his reading of Helena Blavatsky.[19]

Theosophist and composer Dane Rudhyar wrote that Scriabin was "the one great pioneer of the new music of a reborn Western civilization, the father of the future musician", and an antidote to "the Latin reactionaries and their apostle, Stravinsky" and the "rule-ordained" music of "Schoenberg's group." Scriabin developed his own very personal and abstract mysticism based on the role of the artist in relation to perception and life affirmation. His ideas on reality seem similar to Platonic and Aristotelian theory though much less coherent. The main sources of his philosophy can be found in his numerous unpublished notebooks, one in which he famously wrote "I am God". As well as jottings there are complex and technical diagrams explaining his metaphysics. Scriabin also used poetry as a means in which to express his philosophical notions, though arguably much of his philosophical thought was translated into music, the most recognizable example being the Ninth Sonata ("the Black Mass").

Though Scriabin's late works are often considered to be influenced by synesthesia, a condition wherein one experiences sensation in one sense in response to stimulus in another, it is doubted that Scriabin actually experienced this.[31][32] His colour system, unlike most synesthetic experience, accords with the circle of fifths: it was a thought-out system based on Sir Isaac Newton's Opticks. Note that Scriabin did not, for his theory, recognize a difference between a major and a minor tonality of the same name (for example: c-minor and C-Major). Indeed, influenced also by the doctrines of theosophy, he developed his system of synesthesia toward what would have been a pioneering multimedia performance: his unrealized magnum opus Mysterium was to have been a grand week-long performance including music, scent, dance, and light in the foothills of the Himalayas Mountains that was somehow to bring about the dissolution of the world in bliss.

In his autobiographical Recollections, Sergei Rachmaninoff recorded a conversation he had had with Scriabin and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov about Scriabin's association of colour and music. Rachmaninoff was surprised to find that Rimsky-Korsakov agreed with Scriabin on associations of musical keys with colors; himself skeptical, Rachmaninoff made the obvious objection that the two composers did not always agree on the colours involved. Both maintained that the key of D major was golden-brown; but Scriabin linked E-flat major with red-purple, while Rimsky-Korsakov favored blue. However, Rimsky-Korsakov protested that a passage in Rachmaninoff's opera The Miserly Knight accorded with their claim: the scene in which the Old Baron opens treasure chests to reveal gold and jewels glittering in torchlight is written in D major. Scriabin told Rachmaninoff that "your intuition has unconsciously followed the laws whose very existence you have tried to deny."

While Scriabin wrote only a small number of orchestral works, they are among his most famous, and some are performed frequently. They include a piano concerto (1896), and five symphonic works, including three numbered symphonies as well as The Poem of Ecstasy (1908) and Prometheus: The Poem of Fire (1910), which includes a part for a machine known as a "clavier à lumières", known also as a Luce (Italian for "Light"), which was a colour organ designed specifically for the performance of Scriabin's tone poem. It was played like a piano, but projected coloured light on a screen in the concert hall rather than sound. Most performances of the piece (including the premiere) have not included this light element, although a performance in New York City in 1915 projected colours onto a screen. It has been claimed erroneously that this performance used the colour-organ invented by English painter A. Wallace Rimington when in fact it was a novel construction supervised personally and built in New York specifically for the performance by Preston S. Miller, the president of the Illuminating Engineering Society.

On November 22, 1969, the work was fully realized making use of the composer’s color score as well as newly developed laser technology on loan from Yale’s Physics Department, by John Mauceri and the Yale Symphony Orchestra and designed by Richard N. Gould, who projected the colors into the auditorium that were reflected by the Mylar vests worn by the audience.[33] The Yale Symphony repeated the presentation in 1971 [34] and brought the work to Paris that year for what was perhaps its Paris premiere at the Théâtre des Champs Élysées. The piece was reprised at Yale once again in 2010 (as conceived by Anna M. Gawboy on YouTube, who, with Justin Townsend, has published ‘Scriabin and the Possible’).[35]

Scriabin's original colour keyboard, with its associated turntable of coloured lamps, is preserved in his apartment near the Arbat in Moscow, which is now a museum dedicated to his life and works.

Recordings and performers

Scriabin himself made recordings of 19 of his own works, using 20 piano rolls, six for the Welte-Mignon, and 14 for Ludwig Hupfeld of Leipzig.[36] The Welte rolls were recorded during early February 1910, in Moscow, and have been replayed and published on CD. Those recorded for Hupfeld include the piano sonatas Opp. 19 and 23.[37] While this indirect evidence of Scriabin's pianism prompted a mixed critical reception, close analysis of the recordings within the context of the limitations of the particular piano roll technology can shed light on the free style that he favoured for the performance his own works, characterized by extemporary variations in tempo, rhythm, articulation, dynamics, and sometimes even the notes themselves.[38]

Pianists who have performed Scriabin to particular critical acclaim include Vladimir Sofronitsky, Vladimir Horowitz and Sviatoslav Richter. Sofronitsky never met the composer, as his parents forbade him to attend a concert due to illness. The pianist said he never forgave them; but he did marry Scriabin's daughter Elena. According to Horowitz, when he played for the composer as an 11-year-old child, Scriabin responded enthusiastically and encouraged him to pursue a full musical and artistic education.[39] When Sergei Rachmaninoff performed Scriabin's music his playing style was criticized by the composer and his admirers as being earthbound.[40][41]

Surveys of the solo piano works have been recorded by Gordon Fergus-Thompson, Pervez Mody, Maria Lettberg, and Michael Ponti. The complete published sonatas have also been recorded by, among others, Dmitri Alexeev, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Håkon Austbø, Boris Berman, Bernd Glemser, Marc-André Hamelin, Yakov Kasman, Ruth Laredo, John Ogdon, Roberto Szidon, Robert Taub, Anatol Ugorski, Mikhail Voskresensky, and Igor Zhukov.

Other prominent performers of his piano music include Samuil Feinberg, Nikolai Demidenko, Marta Deyanova, Sergio Fiorentino, Andrei Gavrilov, Emil Gilels, Glenn Gould, Andrej Hoteev, Evgeny Kissin, Anton Kuerti, Piers Lane, Eric Le Van, Alexander Melnikov, Stanislav Neuhaus, Artur Pizarro, Mikhail Pletnev, Jonathan Powell, Burkard Schliessmann, Grigory Sokolov, Yevgeny Sudbin, Matthijs Verschoor, Arcadi Volodos, Roger Woodward and Evgeny Zarafiants.

Reception and influence

Scriabin's funeral was attended by such numbers that tickets had to be issued. Rachmaninoff went on tour, playing only Scriabin's music. Sergei Prokofiev admired the composer, and his Visions fugitives bears great likeness to Scriabin's tone and style. Another admirer was the British-Parsi composer Kaikhosru Sorabji who strenuously collected the obscure works of Scriabin while living in Essex as a youth. Sorabji promoted Scriabin even during the years when Scriabin's popularity had decreased greatly. Aaron Copland praised Scriabin's thematic material as "truly individual, truly inspired", but criticized Scriabin for putting "this really new body of feeling into the strait-jacket of the old classical sonata-form, recapitulation and all", calling this "one of the most extraordinary mistakes in all music."[42]

|

Prélude Op. 11, No. 1

(728 kB) Prélude Op. 11, No. 2

(1492 kB) Mazurka Op. 40, No. 2

(677 kB) |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

The work of Nikolai Roslavets, unlike that of Prokofiev and Stravinsky, is often seen as a direct extension of Scriabin's. Unlike Scriabin's, however, Roslavets' music was not explained with mysticism and eventually was given theoretical explication by the composer. Roslavets was not alone in his innovative extension of Scriabin's musical language, however, as quite a few Soviet composers and pianists such as Samuil Feinberg, Sergei Protopopov, Nikolai Myaskovsky, and Alexander Mosolov followed this legacy until Stalinist politics quelled it in favor of Socialist Realism.[43]

Scriabin's music was greatly disparaged in the West during the 1930s. Sir Adrian Boult refused to play the Scriabin selections chosen by the BBC progammer Edward Clark, calling it "evil music", and even issued a ban on Scriabin's music from broadcasts in the 1930s. In 1935, Gerald Abraham described Scriabin as a "sad pathological case, erotic and egotistic to the point of mania".[44] Scriabin has since undergone a total rehabilitation.

In 2009, Roger Scruton described Scriabin as "one of the greatest of modern composers".[45]

Relatives and descendants

.jpg)

He was not a relative of Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov, whose birth name was Vyacheslav Skryabin. In his memoirs published by Felix Chuyev under the Russian title "Молотов, Полудержавный властелин", Molotov explains that his brother Nikolay Skryabin, who was also a composer, had adopted the name Nikolay Nolinsky in order not to be confused with Alexander Scriabin.

Scriabin's second wife Tatiana Fyodorovna Schlözer was the niece of the pianist and possible composer Paul de Schlözer. Her brother was the music critic Boris de Schlözer.

Scriabin was the uncle of Metropolitan Anthony Bloom of Sourozh, a renowned bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church who directed the Russian Orthodox diocese in Great Britain between 1957 and 2003.

Scriabin had seven children in total: from his first marriage Rimma, Elena, Maria and Lev, and from his second Ariadna, Julian and Marina. Rimma died in 1905 from intestinal issues at the age of seven.[46]

Elena Scriabina married the pianist Vladimir Sofronitsky (after the composer's death, hence Sofronitsky never met his father-in-law). Their daughter is the Canadian pianist Viviana Sofronitsky. Maria Skryabina (1901–1989) was an actress at the Second Moscow Art Theatre and the wife of director Vladimir Tatarinov.

Lev also died at the age of seven, in 1910. At this point, relations with Scriabin's first wife had significantly deteriorated, and Scriabin did not meet her at the funeral.[47]

Scriabin's daughter Ariadna Scriabina (1906–1944) became a hero of the French Resistance, posthumously awarded the Croix de guerre and Médaille de la Résistance. She was born in Italy, converted to Judaism (taking the name Sarah), and her third marriage was to the poet and WWII Resistance fighter David Knut. She co-founded the Zionist resistance movement Armée Juive and was responsible for communications between the command in Toulouse and the partisan forces in the Tarn district and for taking weapons to the partisans, which resulted in her death when she was ambushed by the French Militia.

One of Ariadna Scriabina's daughters (by her first marriage), Betty Knut-Lazarus, became a teenage heroine of the French Resistance, winning the Silver Star personally from George S. Patton, as well as the French Croix de guerre. After the war she became an active member of the Lehi (Stern Gang), undertaking special operations for the militant group and she became famous after being imprisoned in 1947 for launching a letter bomb campaign against British targets,[48] and planting explosives on British ships which had been trying to prevent Jewish immigrants from travelling to Mandatory Palestine. Regarded as a heroine in France she was released prematurely, but imprisoned a year later in Israel for being allegedly involved in the killing of Folke Bernadotte,[49] but the charges were subsequently dropped. After her release from prison, she settled at the age of 23 in Beersheba in Southern Israel, where she opened a nightclub, before her early death at the age of 38.[50]

Three of Ariadna Scriabina's children immigrated to Israel after the war, where two became soldiers, and one of her grand-sons, Elisha Abas is an Israeli concert pianist.[51]

Julian Scriabin was a composer and pianist in his own right, but died by drowning at age eleven in Ukraine.[52]

See also

- 20th century classical music

- ANS synthesizer

- Atonality

- Music written in all 24 major and minor keys

- Mystic chord

- Romantic music

- Synesthesia in art

- Synthetic chord

References

- ↑ Scientific transliteration: Aleksandr Nikolajevič Skrjabin; also transliterated variously as Skriabin, Skryabin, and (in French) Scriabine.

- ↑ "Scriabin". Merriam-Webster Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

"Scriabin". Random House Dictionary. Dictionary.com. Retrieved 6 February 2014. - ↑ The British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore, in footnote 62, page 39 of his book Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003) takes issue with the common claim of Scriabin being a "cousin" or a "relative" of Vyacheslav Molotov, born Vyacheslav Mikhailovitch Skryabin. (Translated from a note of this article on the French WP.)

- ↑ Scriabin, Extensive Biography. Pianosociety.com. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ↑ E. E. Garcia (2004): Rachmaninoff and Scriabin: Creativity and Suffering in Talent and Genius. Psychoanalytic Review, 91: 423–42.

- ↑ Bowers, Faubion (1966). "Scriabin Again and Again". Aspen Magazine (New York: Roaring Fork Press) (2). OCLC 50534422. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Bowers, Faubion (1996). Scriabin, a Biography. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-28897-0. OCLC 33405309.

- ↑ Powell, Jonathan. "Skryabin, Aleksandr Nikolayevich". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 February 2014.(subscription required)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Scholes, Percy (1969) [1924]. Crotchets: A Few Short Musical Notes. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-7222-5836-1. OCLC 855415. ISBN is for January 2001 edition.

- ↑ Bowers, Faubion. The New Scriabin. p. 47.

- ↑ The Concise Edition of Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, 8th ed. Revised by Nicolas Slonimsky. New York, Schirmer Books, 1993. p. 921 ISBN 0-02-872416-X

- ↑ Gilles Potvin. "Alfred La Liberté". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ↑ Minderovic, Zoran. "Alexander Scriabin". Biography. Allmusic. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ↑ Benson, Robert E. (October 2000). "Scriabin's Mysterium". Nuances. Preparation for The Final Mystery. Classical CD Review. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ↑ Shelokhonov, Steve. "Alexander Scriabin". Mini Biography. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ↑ Bowers & 1969 2:264.

- ↑ Roberts, Peter Deane (2002). Aleksandr Skryabin. Conneticuit: Greenwood Press. p. 483.

- ↑ MacDonald, p. 7

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Samson, Jim (1977). Music in Transition: A Study of Tonal Expansion and Atonality, 1900–1920. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-02193-6. OCLC 3240273.

- ↑ Samson, Jim (1977). Music in Transition: A Study of Tonal Expansion and Atonality, 1900–1920. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 156–157. ISBN 0-393-02193-9.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Sabbagh, Peter (2001). The Development of Harmony in Scriabin's Works. ISBN 1-58112-595-X.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Sabbagh 2003, p. 16.

- ↑ Sabbagh 2003, p. 24.

- ↑ Taken from Music-Konzepte Nos. 32–33, a.a.,O.p.8.

- ↑ Sabbagh 2003, p. 40.

- ↑ Leonid Sabaneev, Vospominanija o Skrjabine, Moscow 1925, p.47. quoted in Music-Konzepte 32/33,a.a.O., p.8.

- ↑ Leonid Sabaneev, Vospominanija o Skrjabine, Moscow 1925, p.220. quoted in Music-Konzepte 32/33,a.a.O., p.8.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Kallis, Vasily (2008). Principles of Pitch Organization in Scriabin's Early Post-tonal Period: The Piano Miniatures. Society for Music Theory, Volume 14, Number 3.

- ↑ Hedon, Claude (1982–83). Skryabin's New Harmonic Language in his Sixth Sonata. Journal of Musicological Research No.4. p. 354.

- ↑ Guenther, Roy J. (1979). Varvara Dernova's Garmoniia Skriabina: A Translation and Critical Commentary. Ph.D. Dissertation, Catholic University of America. p. 67.

- ↑

- Harrison, John (2001). Synaesthesia: The Strangest Thing, ISBN 0-19-263245-0: "In fact, there is considerable doubt about the legitimacy of Scriabin's claim, or rather the claims made on his behalf, as we shall discuss in Chapter 5." (pp. 31–32).

- ↑ B. M. Galeyev and I. L. Vanechkina (August 2001). "Was Scriabin a Synesthete?", Leonardo, Vol. 34, Issue 4, pp. 357 – 362: "authors conclude that the nature of Scriabin's 'color-tonal' analogies was associative, i.e. psychological; accordingly, the existing belief that Scriabin was a distinctive, unique 'synesthete' who really saw the sounds of music—that is, literally had an ability for 'co-sensations'—is placed in doubt."

- ↑ Ballard, Lincoln M. "A Russian Mystic in the Age of Aquarius: The U.S. Revival of Alexander Scriabin in the 1960s". Project Muse. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ↑ Frisch, Walter (February 22, 1971). "'Prometheus' Transcends". Yale Daily News.

- ↑ http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.12.18.2/mto.12.18.2.gawboy_townsend.php

- ↑ Smith, Charles Davis (1994). The Welte-Mignon: Its Music and Musicians. Vestal, NY: The Vestal Press, for the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors' Association. ISBN 1-879511-17-7.

- ↑ Sitsky, Larry (1990). The Classical Reproducing Piano Roll. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-25496-6.

- ↑ Leikin, Anatole (1996). "The Performance of Scriabin's Piano Music: Evidence from the Piano Rolls". Performance Practice Review 9 (1): 97–113. ISSN 1044-1638. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ↑ Horowitz plays Scriabin in Moscow on YouTube

- ↑ Rimm, p. 145

- ↑ Downes, p. 99

- ↑ Copland, Aaron (1957). What to Listen for in Music. New York: McGraw-Hill. OCLC 269329.

- ↑ Richard Taruskin (20 February 2005). "Restoring Comrade Roslavets". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ↑ Ballard, Lincoln. "Lincoln Ballard, ''Defining Moments: Vicissitudes in Scriabin’s Twentieth-Century Reception''". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2014-04-14.

- ↑ Scruton, Roger (2009). Understanding Music: Philosophy and Interpretation. Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd. p. 183. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ Khanon, Yurij (1995). Скрябин как лицо [Scriabin the Person] (in Russian). St. Petersburg: Liki Rossii.

- ↑ Pryanishnikov and Tompakov (1985). Летопись жизни и творчества А. Н.Скрябина [Chronicles of the Life and Art of A. N. Scriabin] (in Russian). Muzyka.

- ↑ BLUSHED AT BOMB PLOT CHARGE, Thursday 26 August 1948, Morning Bulletin Rockhampton

- ↑ Lazaris, V. (2000). Три женщины. Tel Aviv: Lado, pp. 363–368

- ↑ בטי קנוט־לזרוס - סיפורה של לוחמת נשכחת Oded Bar-Meir, 05.05.11

- ↑ "Elisha Abas – the official website". Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- ↑ Slonimsky, Nicolas (1993). The Concise Edition of Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, 8th ed. New York: Schirmer Books.

Sources

- Downes, Stephen (2010). Music and Decadence in European Modernism: The Case of Central and Eastern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76757-6.

- Macdonald, Hugh (1978). Skryabin. Oxford studies of composers (15). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-315438-2.

- Rimm, Robert (2002). The Composer-pianists: Hamelin and The Eight. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-072-1.

- Sabbagh, Peter (2003). The Development of Harmony in Scriabin's Works. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 1-58112-595-X.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Alexander Scriabin |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Alexander Scriabin. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alexander Scriabin. |

- UK Scriabin Association

- Scriabin Society of America

- Brief biography and sound files on Ubuweb

- Alexander Scriabin discography at MusicBrainz

- Works by or about Alexander Scriabin in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Scriabin Liner Notes Russian-born pianist Yevgeny Sudbin discusses Scriabin's work and life.

Scores

- Free scores by Alexander Scriabin at the International Music Score Library Project

- Scriabin's Sheet Music by Mutopia Project

- www.kreusch-sheet-music.net — Free Scores by Alexander Scriabin

Recordings

- Scriabin's own recording of the third and fourth Movements from his Piano Sonata, no. 3, Op. 23 (The Pianola Institute)*

- Piano Rolls (The Reproducing Piano Roll Foundation)

|