Alexamenos graffito

The Alexamenos graffito (also known as the graffito blasfemo)[1]:393 is an inscription carved in plaster on a wall near the Palatine Hill in Rome, now in the Palatine Antiquarium Museum. It may be the earliest surviving image of Jesus and is alleged to be among the earliest known pictorial representations of the Crucifixion of Jesus, together with an engraved gem.[2] It is scratched on plaster and was estimated to have been carved c. 200 AD. [3]

Content

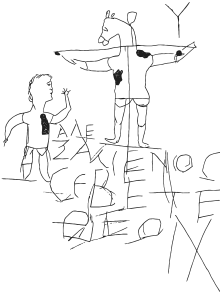

The image depicts a human-like figure affixed to a cross and possessing the head of a donkey. In the top right of the image is what has been interpreted as either the Greek letter upsilon or a tau cross.[1] To the left of the image is a young man, apparently intended to represent Alexamenos,[4] a Roman soldier/guard, raising one hand in a gesture possibly suggesting worship.[5][6] Beneath the cross is a caption written in crude Greek: Αλεξαμενος ϲεβετε θεον. ϲεβετε can be understood as a variant spelling (possibly a phonetic misspelling)[7] of Standard Greek ϲεβεται, which means "worships". The full inscription would then be translated as "Alexamenos worships [his] God".[7][8][9] Several other sources suggest "Alexamenos worshipping God", or similar variants, as the intended translation.[10][11][12][13]

Date

No clear consensus has been reached on when the image was made. Dates ranging from the late 1st to the late 3rd century have been suggested,[14] with the beginning of the 3rd century thought to be the most likely.[8][15][16]

Discovery and location

The graffito was discovered in 1857 when a building called the domus Gelotiana was unearthed on the Palatine Hill. The emperor Caligula had acquired the house for the imperial palace, which, after Caligula died, became used as a Paedagogium (boarding school) for the imperial page boys. Later, the street on which the house sat was walled off to give support to extensions to the buildings above, and it thus remained sealed for centuries.[17] The graffito is today housed in the Palatine antiquarium in Rome.[18]

Interpretation

The inscription is accepted by authoritative sources, such as the Catholic Encyclopedia,[19] to be a mocking depiction of a Christian in the act of worship. The donkey's head and crucifixion would both have been considered insulting depictions by contemporary Roman society. Crucifixion continued to be used as an execution method for the worst criminals until its abolition by the emperor Constantine in the 4th century, and the impact of seeing a figure on a cross is comparable to the impact today of portraying a man with a hangman's noose around his neck or seated in an electric chair.[20]

It seems to have been commonly believed at the time that Christians practiced onolatry (donkey-worship). That was based on the misconception that Jews worshipped a god in the form of a donkey, a prejudice of unclear origin. Tertullian, writing in the late 2nd or early 3rd century, reports that Christians, along with Jews, were accused of worshipping such a deity. He also mentions an apostate Jew who carried around Carthage a caricature of a Christian with ass's ears and hooves, labeled Deus Christianorum Onocoetes ("the God of the Christians begotten of an ass").[21]

Others have suggested that the graffito depicts worship of the Egyptian gods Anubis[9] or Seth,[22] or that the young man is actually engaged in a gnostic ceremony involving a horse-headed figure and that rather than a Greek upsilon it is a tau cross at the top right of the crucified figure.[1]:393–394

It has also been suggested that both the graffito and the roughly contemporary gems with Crucifixion images are related to heretical groups outside the Church.[23]

Significance

There is some controversy about whether the veneration of the crucifix depicted in the graffito was actually practiced by contemporary Christians, or whether, like the ass's head, it was an added to the image to ridicule Christian beliefs. According to one argument, the alleged presence of a loincloth on the crucified figure, in contrast to usual Roman procedure in which the condemned was completely naked, proves the artist must have based his illustration on an activity he had observed Alexamenos or others performing.[24] Against this it has been argued that the cross was not actually used in worship until the 4th and 5th centuries.[25]

"Alexamenos fidelis"

In the next chamber, another inscription in a different hand reads Alexamenos fidelis, Latin for "Alexamenos is faithful" or "Alexamenos the faithful".[26] This may be a riposte by an unknown party to the mockery of Alexamenos represented in the graffito.[16]

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Bayley, Harold (1920). Archaic England: An essay in deciphering prehistory from megalithic monuments, earthworks, customs, coins, place-names, and faerie superstitions. Chapman & Hall.

- ↑ Schiller, 89-90, fig. 321

- ↑ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/graffito.html

- ↑ Rodolfo Lanciani, Ancient Rome in the Light of Recent Discoveries, 1898, chapter 5 'The Palace of the Caesars'

- ↑ Thomas Wright, Frederick William Fairholt, A History of Caricature and Grotesque in Literature and Art, Chatto and Windus, 1875, p. 39

- ↑ Augustus John Cuthbert Hare, Walks in Rome, Volume 1, Adamant Media Corporation, 2005, p. 201

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Rodney J. Decker, The Alexamenos Graffito

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 David L. Balch, Carolyn Osiek, Early Christian Families in Context: An Interdisciplinary Dialogue, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003, p. 103

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 B. Hudson MacLean, An introduction to Greek epigraphy of the Hellenistic and Roman periods from Alexander the Great down to the reign of Constantine, University of Michigan Press, 2002, p. 208

- ↑

Hassett, Maurice M. (1907). "The Ass (in Caricature of Christian Beliefs and Practices)". Catholic Encyclopedia 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Hassett, Maurice M. (1907). "The Ass (in Caricature of Christian Beliefs and Practices)". Catholic Encyclopedia 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ↑ "Home Page - Concordia Theological Seminary". Ctsfw.edu. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- ↑ "A Sociological Analysis of Graffiti" (PDF). Sustain.ubc.ca. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- ↑ Charles William King (1887). "Gnostics and their Remains". p. 433 note 12. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- ↑ Hans Schwarz, Christology, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1998, p. 207

- ↑ Schiller, 90

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Michael Green, Evangelism in the Early Church, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, p. 244

- ↑ Edward L Cutts, History of Early Christian Art, Kessinger Publishing, 2004, p. 200

- ↑ Rodney J. Decker, The Alexamenos Graffito

- ↑

Drum, Walter (1910). "The Incarnation". Catholic Encyclopedia 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Drum, Walter (1910). "The Incarnation". Catholic Encyclopedia 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ N. T. Wright, What Saint Paul Really Said: Was Paul of Tarsus the Real Founder of Christianity?, 1997, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, p. 46

- ↑ Tertullian, Ad nationes, 1:11, 1:14

- ↑

Hasset, Maurice M. (1907). "The Ass (in Caricature of Christian Beliefs and Practices)". Catholic Encyclopedia 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.. "Wünsch, however, conjectures that the caricature may have been intended to represent the god of a Gnostic sect which identified Christ with the Egyptian ass-headed god Typhon-Seth (Bréhier, Les origines du crucifix, 15 sqq.). But the reasons advanced in favour of this hypothesis are not convincing."

Hasset, Maurice M. (1907). "The Ass (in Caricature of Christian Beliefs and Practices)". Catholic Encyclopedia 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.. "Wünsch, however, conjectures that the caricature may have been intended to represent the god of a Gnostic sect which identified Christ with the Egyptian ass-headed god Typhon-Seth (Bréhier, Les origines du crucifix, 15 sqq.). But the reasons advanced in favour of this hypothesis are not convincing." - ↑ Schiller, 89-90

- ↑

Marucchi, Orazio; Cabrol, Fernand & Thurston, Herbert (1908). "Cross and Crucifix". Catholic Encyclopedia 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Marucchi, Orazio; Cabrol, Fernand & Thurston, Herbert (1908). "Cross and Crucifix". Catholic Encyclopedia 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ David L. Balch, Carolyn Osiek, Early Christian Families in Context: An Interdisciplinary Dialogue, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003, p. 103, footnote 83

- ↑

Hassett, Maurice M. (1909). "Graffiti". Catholic Encyclopedia 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Hassett, Maurice M. (1909). "Graffiti". Catholic Encyclopedia 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

References

- Schiller, Gertrud. Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II,1972 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0-85331-324-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alexamenos graffito. |

- The Alexamenos Graffito: page by Rodney J. Decker

- Alexamenos and pagan perceptions of Christians

- Alexamenos: a Christian mocked for believing in a crucified God

See also and: Josephe Flavius, Contre Apion, II (VII), 2.80, traduit per Leon Blum, LBL, 1930, 72-74. Norman Walker,The Riddle of the Ass's Head..., ZAW, 9, 1963, 219-231.