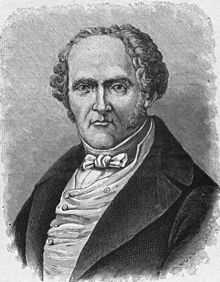

Albert Brisbane

Albert Brisbane (1809–1890) was an American utopian socialist and is remembered as the chief popularizer of the theories of Charles Fourier in the United States. Brisbane was the author of several books, notably Social Destiny of Man (1840), as well as the Fourierist periodical The Phalanx. He also founded the Fourierist Society in New York in 1839 and backed several other phalanx communes in the 1840s and 1850s.

Biography

Early years

Albert Brisbane was born in 1809 in Batavia, New York. He was the only son of a wealthy landowner.[1] Brisbane's mother was of English descent and his father a Scot who had abandoned the Scottish Presbyterian Church in protest over its regimented rituals.[2]

Brisbane developed an affection for knowledge at an early age and as an inquisitive youth he learned various mechanical skills in the small carpentry, blacksmith, and saddle shops of Batavia.[3] Unsatisfied with the quality of education in Batavia and with visions of an illustrious future for his son, Brisbane's father took him to New York City to enroll him in a high quality school there.[4] His New York schooling would ultimately be followed by six years of education abroad,[5] with Brisbane studying philosophy in Paris and Berlin. making the acquaintance of a number of prominent European intellectuals and political figures during the course of his studies.[1]

In Berlin Brisbane became interested in the ideas of socialism, becoming an advocate of the ideas of Henri de Saint-Simon.[6] Brisbane was very active with the promotion of Saint-Simon's ideas for a time, but became disaffected when the movement split between the followers of Barthélemy Enfantin and Amand Bazard and dropped out of the Saint-Simondian movement altogether.[6] Brisbane would later dismiss Saint-Simon's doctrines as "artificial and in some respects false."[7]

Conversion to Fourierism

Searching for new ideas, Brisbane read a newly published short work by philosopher Charles Fourier (1772-1837) entitled Treatise on Domestic and Agricultural Association and was immediately converted to the writer's ideas. Fourier, a French philosopher and writer, spent the greater part of his life attempting to uncover universal laws which he believed governed society so that productive enterprise could be reorganized on a rational basis, production expanded, and human needs more readily fulfilled.[8] Fourier believed in a fundamental harmony of the universe and a preordained series of periods through which societies needed to necessarily travel from their primitive to their advanced state, and he considered himself a scientific discoverer akin to Isaac Newton.[8]

In 1832 Brisbane left for Paris, where he would stay two years studying Fourier's system, including obtaining direct tutelage from the 60-year old theorist himself.[6] He made the acquaintance of other devotees of Fourier's ideas during this initial phase of the Fourierist movement.[6] He would return to the United States a committed believer and proselytizer of the Fourier's idea of association and began work on a book to expound the ideas of his late master.[6] Brisbane's first and most famous book, Social Destiny of Man, would see print in 1840.[6]

Brisbane's ideas

Brisbane accepted Fourier's ideas as a matter of faith, believing that the "social destiny of man" was an immutable force of nature; once the laws of this development were identified and publicized, he believed, the regeneration and transformation of the world would be rapid and effective.[9] On the heels of his first successful book, in 1843 Brisbane published another adaptation of Fourier to American conditions, a book entitled Association: Or, A Concise Exposition of the Practical Part of Fourier's Social Science.[9]

Brisbane argued that the remedy to society's ills lay in the adoption of more efficient forms of production, based upon the principle of harmony of the owners of capital and those employed by them.[10] He did not envision the elimination of the role of the capitalist, but rather the regulation of distribution of the product of labor between capitalist and worker on a more equitable basis.[11] Paramount to increasing production, Brisbane believed, was a reorganization of society into various subdivisions called "groups," "series," and "sacred legions," based upon the natural affinities of their participants.[11] This reorganization would boost production by building enthusiasm for labor, gathering individuals of like proclivities for common tasks.[11]

Following Fourier, Brisbane also sought the revolutionization of the family unit, proclaiming the individual home to be possessed of "monotony," "anti-social spirit," and the "absence of emulation," through which, he felt, it "debilitates the energies of the soul, and produces apathy and intellectual death."[11] In opposition to this "selfishness," Brisbane opposed the communal ideal of association, living in collective dwellings and sharing the common table.[12]

Brisbane cast the adoption of Fourier's system in millennial terms, asserting that

"Association will establish Christianity practically upon Earth. It will make the love of God and the love of the neighbor the greatest desire, and the practice of all men. Temptation to wrong will be taken from the paths of men, and a thousand perverting and degrading circumstances and influences will be purged from the social world."[13]

Brisbane at zenith

Brisbane's 1840 book was well-received and it enjoyed immediate success, gaining a broad readership among those concerned with the problems of society and helping to launch the Fourierist movement in the United States.[14] Among those who read Brisbane's book and was thereby converted to the ideas of socialism was a young New York newspaper publisher, Horace Greeley, later elected to the US House of Representatives.[14] Greeley would provide valuable service to the Fourierist movement by advancing its ideas in the pages of his newspaper of that day, The New Yorker, throughout 1840 and 1841, and offering Brisbane a column in his successor publication, the New York Tribune, from the time of its establishment in March 1842.[15]

A groundswell of enthusiasm resulted from coverage of the ideas of Association in the New York Tribune, and from 1843 to 1845 more than 30 Fourierian "Phalanxes" were established in a number of northern and midwestern states. In 1844, Brook Farm, already an established Transcendentalist agrarian community in Massachusetts, formally declared itself a Fourierist community based on Brisbane's teachings.

A national movement of "Associationists' began to take form in 1843 and 1844, with a founding convention of the General Association for the Friends of Association in the United States held in New York City from April 4–6, 1844, attended by delegates from as far away as Maine and Virginia.[16] The convention made a point of renouncing the fanciful, conjectural aspects of Fourier's writings, instead endorsing the concrete plan of association derived from his writings, in addition to its underlying philosophical framework.[16] Work was done to create a formal "Union of Associations" to help coordinate the efforts of the myriad of small phalanxes coming into existence, and a meeting of such a group was planned for the following October.[17]

At this critical juncture in the emergence of a practical movement, with 10 phalanxes already in existence and others at the planning stage, Albert Brisbane, the uncontested leader of Fourierism in America, made the fateful decision to depart for France to study Fourier's manuscripts there and to speak with French Associationists about their experiences.[17] The 8-month trip effectively removed the commanding general of the Fourierist army from the campaign at its most critical juncture and is characterized by a leading historian of the movement as a reflection of Brisbane's "lifelong inability to cope with power and responsibility."[18] With no energetic leader to replace Brisbane, the movement's momentum quickly dissipated.[19]

Second European period

In 1877, Brisbane married again, relocating that fall to Europe with his wife and children with a view towards the education of the latter.[20] The family traveled the continent for two years before taking up resident in Paris.[21] His health in decline and suffering from epilepsy, Brisbane pursued personal intellectual pursuits and tried his hand as an inventor, concentrating in particular on an effort to create an oven which cooked in a vacuum, thereby allowing the baking of bread and pastry without the use of yeast.[22]

Final years, death, and legacy

The family returned to New York state only in the fall of 1889, ostensibly so that Brisbane could build a prototype of the vacuum oven which he had been attempting to perfect.[23] He became ill soon after his arrival, however, and was forced to seek a change of climate to improve his health, traveling to North Carolina, before heading south to Florida, that winter.[24] Together with his wife, Brisbane north to Richmond, Virginia early in the spring of the following year.[24] Good health did not return, however, and late in April Brisbane became bedridden and began to await his inevitable death.[25]

Albert Brisbane died in Richmond early in the morning on May 1, 1890.[26] His body was transported home to Western New York and was buried in the Batavia Cemetery in Batavia.[27]

His son, Arthur Brisbane (1864–1936), became one of the best known American newspaper editors of the 20th century. The papers of father and son are held together as Brisbane Family Papers collection by the Special Collections Research Center of Syracuse University in Syracuse, New York.[28] The Albert Brisbane material is housed in one archival box and includes biographical material, correspondence, microfilm of his diaries from the 1830s, and a 56 page autobiography dated London, 1881.[28]

See also

- Fourierism

- List of Fourierist Associations in the United States

- American Union of Associationists

- Victor Prosper Considerant

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Morris Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States. Revised Fifth Edition. New York, NY: Funk and Wagnalls, 1910; pg. 79.

- ↑ Redelia Brisbane, Albert Brisbane: A Mental Biography with a Character Study. Boston, MA: Arena Publishing Co., 1893; pg. 50.

- ↑ Brisbane, Albert Brisbane, pg. 54.

- ↑ Brisbane, Albert Brisbane, pg. 56.

- ↑ Brisbane, Albert Brisbane, pg. 5.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 80.

- ↑ Hoagland, "Humanitarianism," pg. 497.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Henry E. Hoagland, "Humanitarianism (1840-1860)" in John R. Commons, et al., History of Labour in the United States: Volume 1. New York: Macmillan, 1918; pp. 496-497.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Hoagland, "Humanitarianism," pg. 498.

- ↑ Hoagland, "Humanitarianism," pp. 498-499.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Hoagland, "Humanitarianism," pg. 499.

- ↑ Hoagland, "Humanitarianism," pg. 500.

- ↑ Albert Brisbane, A Concise Exposition of the Doctrine of Association: Or, Plan for a Re-organization of Society. New York, NY: J.S. Redfield, 1844; pg. 2.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 81.

- ↑ Hoagland, "Humanitarianism," pg. 501.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 232.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 233.

- ↑ The words are those of Carl J. Guarneri. See: Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 233.

- ↑ Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 234.

- ↑ Brisbane, Albert Brisbane, pg. 22.

- ↑ Brisbane, Albert Brisbane, pg. 26.

- ↑ Brisbane, Albert Brisbane, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Brisbane, Albert Brisbane, pg. 38.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Brisbane, Albert Brisbane, pg. 39.

- ↑ Brisbane, Albert Brisbane, pp. 42-43.

- ↑ Brisbane, Albert Brisbane, pg. 43.

- ↑ Robert T. Englert, "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Batavia Cemetery," New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, August 2001.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 KM, "Brisbane Family Papers: An Inventory of its Papers at Syracuse University," Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries, Nov. 1991.

Works

- Social Destiny of Man, Or, Association and Reorganization of Industry. Philadelphia, PA: C.F. Stollmeyer, 1840.

- Association: Or, A Concise Exposition of the Practical Part of Fourier's Social Science. New York, NY: Greeley & McElrath (and others), 1843.

- A Concise Exposition of the Doctrine of Association: Or, Plan for a Re-organization of Society. New York, NY: J.S. Redfield, 1844.

- Theory of the Functions of the Human Passions Followed by an Outline View of the Fundamental Principles of Fourier's Theory of Social Science. New York, NY: Miller, Orton, & Mulligan, 1856.

- "Philosophy of Money: A New Currency and a New Credit System," article in symposium of unknown origin. 1863.

- General Introduction to Social Science: Part First: Introduction to Fourier's Theory of Social Organization. New York, NY: C.P. Somerby, 1876.

Further reading

- Redelia Brisbane, Albert Brisbane: A Mental Biography with a Character Study. Boston, MA: Arena Publishing Co., 1893.

- Carl J. Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative: Fourierism in Nineteenth-Century America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991.

- Charles A. Madison, "Albert Brisbane: Social Dreamer," The American Scholar, vol. 12, no. 3 (Summer 1943), pp. 284–296.

- Robert Carl Olson, Brisbane on Fourierism in America. MA thesis. University of Iowa, 1964.

- Richard Norman Pettitt, Albert Brisbane: Apostle of Fourierism in the United States, 1834-1890. PhD dissertation. Miami University, 1982.

- Lloyd Earl Rohler, The Utopian Persuasion of Albert Brisbane, First Apostle of Fourierism. PhD dissertation. Indiana University, 1977.

|