Alans

The Alans, or the Alani, occasionally termed Alauni or Halani or Yancai were an Iranian nomadic pastoral people of antiquity.[1]

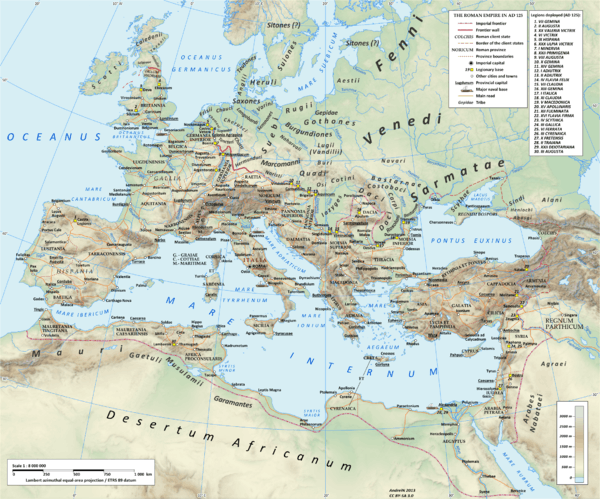

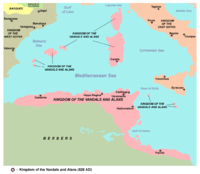

The Alans are first mentioned by Chinese authors in the 1st century BC as living near the Aral Sea as vassals of the Kangju under the name of Yancai, and were later mentioned by Roman authors in the 1st century AD.[1] At the time they settled the region north of the Black Sea, and frequently raided the Parthian Empire and the Caucasian provinces of the Roman Empire.[1] Upon the Hunnic defeat of the Goths on the Pontic Steppe around 375 AD, many of the Alans migrated westwards along with other Germanic tribes. They crossed the Rhine in 406 AD along with the Vandals and Suebi, settling in Orléans and Valence. Around 409 AD they joined the Vandals and Suebi in the crossing of the Pyrenees into the Iberian Peninsula, settling in Lusitania and Carthaginiensis.[2] The Iberian Alans were soundly defeated by the Visigoths 418 AD, and subsequently surrendered their authority to the Hasdingi Vandals.[3] In 428 AD, the Vandals and Alans crossed the Strait of Gibraltar into North Africa, where they founded a powerful kingdom which lasted until its conquest by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century AD.[3]

The Alans who remained under Hunnic rule are said to be the ancestors of the modern Ossetians.[1]

The Alans spoke an Eastern Iranian language which derived from Scytho-Sarmatian and which in turn evolved into modern Ossetian.[4][5][6]

Name

The various forms of Alan — Greek: Ἀλανοί, Alanoi; Chinese: 阿蘭聊 Alanliao (Pinyin) in the 2nd century,[7] 阿蘭 Alan (Pinyin) in the 3rd century[8] — and Iron (a self-designation of the Alans' modern Ossetian descendants, indicating early tribal self-designation) and later Alanguo (阿蘭國)[9] are Iranian dialectical forms of Aryan.[4][10] These and other variants of Aryan (such as Iran), were common self-designations of the Indo-Iranians, the common ancestors of the Indo-Aryans and Iranian peoples to whom the Alans belonged.

The Alans were also known over the course of their history by another group of related names including the variations Asi, As, and Os (Romanian Iasi, Bulgarian Uzi, Hungarian Jász, Russian Jasy, Georgian Osi). It is this name that is the root of the modern Ossetian.[11]

Timeline

Early Alans

The first mentions of names that historians link with the "Alani" appear at almost the same time in Greco-Roman geography and in the Chinese dynastic chronicles.[12]

The Geography (XXIII, 11) of Strabo (64-63 BC through c. AD 24), who was born in Pontus on the Black Sea, but was also working with Persian sources, to judge from the forms he gives to tribal names, mentions Aorsi that he links with Siraces and claims that a Spadines, king of the Aorsi, could assemble two hundred thousand mounted archers in the mid-1st century BC. But the "upper Aorsi" from whom they had split as fugitives, could send many more, for they dominated the coastal region of the Caspian Sea: "and consequently they could import on camels the Indian and Babylonian merchandise, receiving it in their turn from the Armenians and the Medes, and also, owing to their wealth, could wear golden ornaments. Now the Aorsi live along the Tanaïs, but the Siraces live along the Achardeüs, which flows from the Caucasus and empties into Lake Maeotis."

Chapter 123 of the Shiji (whose author, Sima Qian, died c. 90 BC) reports:

Yancai lies some 2,000 li [832 km][13] northwest of Kangju. The people are nomads and their customs are generally similar to those of the people of Kangju. The country has over 100,000 archer warriors, and borders on a great shoreless lake.[14]

The mouth of the Syr Darya or Jaxartes River, which emptied into the Aral Sea was approximately 850 km northwest of the oasis of Tashkent which was an important centre of the Kangju confederacy. This provides remarkable confirmation of the account in the Shiji.

The Later Han Dynasty Chinese chronicle, the Hou Hanshu, 88 (covering the period 25–220 and completed in the 5th century), mentioned a report that the steppe land Yancai was now known as Alanliao (阿蘭聊):

The kingdom of Yancai [literally "Vast Steppe"] has changed its name to the kingdom of Alanliao. They occupy the country and the towns. It is a dependency of Kangju (the Chu, Talas, and middle Jaxartes basins). The climate is mild. Wax trees, pines, and ‘white grass’ [aconite] are plentiful. Their way of life and dress are the same as those of Kangju.[15]

The 3rd century Weilüe states:

Then there is the kingdom of Liu, the kingdom of Yan [to the north of Yancai], and the kingdom of Yancai [between the Black and Caspian Seas], which is also called Alan. They all have the same way of life as those of Kangju. To the west, they border Da Qin [Roman territory], to the southeast they border Kangju [the Chu, Talas, and middle Jaxartes basins]. These kingdoms have large numbers of their famous sables. They raise cattle and move about in search of water and fodder. They are close to a large shoreless lake. Previously they were vassals of Kangju [the Chu, Talas, and middle Jaxartes basins]. Now they are no longer vassals.[16]

By the beginning of the 1st century, the Alans had occupied lands in the northeast Azov Sea area, along the Don and by the 2nd century had amalgamated or joined with the Yancai of the early Chinese records to extend their control all the way along the trade routes from the Black Sea to the north of the Caspian and Aral seas. The written sources suggest that from the end of the 1st century to the second half of the 4th century the Alans had supremacy over the tribal union and created a powerful confederation of Sarmatian tribes.

From a Western point-of-view the Alans presented a serious problem for the Roman Empire, with incursions into both the Danubian and the Caucasian provinces in the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

The 4th century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus considered the Alans to be the former Massagetae.[17]

Physical appearance

The fourth-century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that the Alans were tall, blond and light-eyed:

Nearly all the Alani are men of great stature and beauty; their hair is somewhat yellow, their eyes are terribly fierce.[18]

Archaeology

Archaeological finds support the written sources. P. D. Rau (1927) first identified late Sarmatian sites with the historical Alans. Based on the archaeological material, they were one of the Iranian-speaking nomadic tribes that began to enter the Sarmatian area between the middle of the 1st and the 2nd centuries.

Western sources

Roman sources first mention the Alani in the 1st century and later describe them as a warlike people who specialized in horse breeding. They frequently raided the Parthian empire and the Caucasian provinces of the Roman Empire. In the Vologeses inscription[19] one can read that Vologeses I, the Parthian king c. AD 51-78, in the 11th year of his reign, battled Kuluk, king of the Alani.

The contemporary Jewish historian, Josephus (37–100) supplements this inscription. Josephus reports in the Jewish Wars (book 7, ch. 7.4) how Alans (whom he calls a "Scythian" tribe) living near the Sea of Azov crossed the Iron Gates for plunder (AD 72) and defeated the armies of Pacorus, king of Media, and Tiridates, King of Armenia, two brothers of Vologeses I (for whom the above-mentioned inscription was made):

4. Now there was a nation of the Alans, which we have formerly mentioned somewhere as being Scythians, and inhabiting at the Lake Meotis. This nation about this time laid a design of falling upon Media, and the parts beyond it, in order to plunder them; with which intention they treated with the king of Hyrcania; for he was master of that passage which king Alexander shut up with iron gates. This king gave them leave to come through them; so they came in great multitudes, and fell upon the Medes unexpectedly, and plundered their country, which they found full of people, and replenished with abundance of cattle, while nobody durst make any resistance against them; for Pacorus, the king of the country, had fled away for fear into places where they could not easily come at him, and had yielded up everything he had to them, and had only saved his wife and his concubines from them, and that with difficulty also, after they had been made captives, by giving them a hundred talents for their ransom. These Alans therefore plundered the country without opposition, and with great ease, and proceeded as far as Armenia, laying all waste before them. Now, Tiridates was king of that country, who met them and fought them but had luck to not have been taken alive in the battle; for a certain man threw a net over him from a great distance and had soon drawn him to him, unless he had immediately cut the cord with his sword and ran away and so, prevented it. So the Alans, being still more provoked by this sight, laid waste the country, and drove a great multitude of the men, and a great quantity of the other prey they had gotten out of both kingdoms, along with them, and then retreated back to their own country.

Flavius Arrianus marched against the Alani in the 2nd century and left a detailed report (Ektaxis kata Alanoon or 'War Against the Alans') that is a major source for studying Roman military tactics, but doesn't reveal much about his enemy. In the late 4th century, Vegetius conflates Alans and Huns in his military treatise — Hunnorum Alannorumque natio, the "nation of Huns and Alans" — and collocates Goths, Huns and Alans, exemplo Gothorum et Alannorum Hunnorumque.[20]

In Cathay and the Way Thither, 1866, Henry Yule writes:

The Alans were known to the Chinese by that name, in the ages immediately preceding and following the Christian era, as dwelling near the Aral, in which original position they are believed to have been closely akin to, if not identical with, the famous Massagetæ. Hereabouts also Ptolemy (vi, 14) appears to place the Alani-Scythæ, and Alanæan Mountains. From about 40 B.C. the emigrations of the Alans seem to have been directed westward to the Lower Don; here they are placed in the first century by Josephus and by the Armenian writers; and hence they are found issuing in the third century to ravage the rich provinces of Asia Minor. In 376 the deluge of the Huns on its westward course came upon the Alans and overwhelmed them. Great numbers of Alans are found to have joined the conquerors on their further progress, and large bodies of Alans afterwards swelled the waves of Goths, Vandals, and Sueves, that rolled across the Western Empire. A portion of the Alans, however, after the Hun invasion retired into the plains adjoining Caucasus, and into the lower valleys of that region, where they maintained the name and nationality which the others speedily lost. Little is heard of these Caucasian Alans for many centuries, except occasionally as mercenary soldiers of the Byzantine emperors or the [p. 316] Persian kings. In the thirteenth century they made a stout resistance to the Mongol conquerors, and though driven into the mountains they long continued their forays on the tracts subjected to the Tartar dynasty that settled on the Wolga, so that the Mongols had to maintain posts with strong garrisons to keep them in check. They were long redoutable both as warriors and as armourers, but by the end of the fourteenth century they seem to have come thoroughly under the Tartar rule; for they fought on the side of Toctamish Khan of Sarai against the great Timur.[21]

Migration to Gaul

Around 370, the Alans were overwhelmed by the Huns. They were divided into several groups, some of whom fled westward. A portion of these western Alans joined the Vandals and the Sueves in their invasion of Roman Gaul. Gregory of Tours mentions in his Liber historiae Francorum ("Book of Frankish History") that the Alan king Respendial saved the day for the Vandals in an armed encounter with the Franks at the crossing of the Rhine on December 31, 406). According to Gregory, another group of Alans, led by Goar, crossed the Rhine at the same time, but immediately joined the Romans and settled in Gaul.

Under Biorgor (Biorgor rex Alanorum), they infested Gallia round about, till the reign of Petronius Maximus and then they passed the Alps in winter, and came into Liguria, but were there beaten, and Biorgor slain, by Ricimer commander of the Emperor's forces (year 464).[22][23]

Under Goar, they allied with the Burgundians led by Gundaharius, with whom they installed the usurping Emperor Jovinus. Under Goar's successor Sangiban, the Alans of Orléans played a critical role in repelling the invasion of Attila the Hun at the Battle of Châlons. After the 5th century, however, the Alans of Gaul were subsumed in the territorial struggles between the Franks and the Visigoths, and ceased to have an independent existence. In order to quell unrest, Flavius Aëtius settled large numbers of Alans in various areas, such as in and around Armorica. Several towns with names possibly related to 'Alan', such as Allainville, Yvelines, Alainville-en Beauce, Loiret, Allaines and Allainville, Eure-et-Loir, and Les Allains, Eure, are taken as evidence that a contingent settled in Armorica, Brittany.[24] Other areas of Alans settlement were notably around Orléans and Valentia.[25]

Hispania and Africa

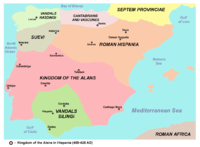

Following the fortunes of the Vandals and Suevi into the Iberian peninsula (Hispania, comprising modern Portugal and Spain) in 409, the Alans led by Respendial settled in the provinces of Lusitania and Carthaginiensis: "Alani Lusitaniam et Carthaginiensem provincias, et Wandali cognomine Silingi Baeticam sortiuntur" (Hydatius). The Siling Vandals settled in Baetica, the Suevi in coastal Gallaecia, and the Asding Vandals in the rest of Gallaecia. Although the barbarians controlled Spain they still compromised a tiny minority among a much larger Hispano-Roman population, approximately 200,000 out of 6,000,000.[2]

In 418 (or 426 according to some authors, cf. e.g. Castritius, 2007), the Alan king, Attaces, was killed in battle against the Visigoths, and this branch of the Alans subsequently appealed to the Asding Vandal king Gunderic to accept the Alan crown. The separate ethnic identity of Respendial's Alans dissolved.[26] Although some of these Alans are thought to have remained in Iberia, most went to North Africa with the Vandals in 429. Later Vandal kings in North Africa styled themselves Rex Wandalorum et Alanorum ("King of the Vandals and Alans").

There are some vestiges of the Alans in Portugal,[27] namely in Alenquer (whose name may be Germanic for the Temple of the Alans, from "Alan Kerk",[28] and whose castle may have been established by them; the Alaunt is still represented in that city's coat of arms), in the construction of the castles of Torres Vedras and Almourol, and in the city walls of Lisbon, where vestiges of their presence may be found under the foundations of the Church of Santa Luzia.

In the Iberian peninsula the Alans settled in Lusitania (cf. Alentejo) and the Cartaginense provinces. They became known in retrospect for their massive hunting and fighting dog of Molosser type, the Alaunt, which they apparently introduced to Europe. The breed is extinct, but its name is carried by a Spanish breed of dog still called Alano, traditionally used in boar hunting and cattle herding. The Alano name, however, has historically been used for a number of dog breeds in a few European countries thought to descend from the original dog of the Alans, such as the German mastiff (Great Dane) and the French Dogue de Bordeaux, among others.

Alans in Europe

Some historians argue that the arrival of the Huns on the European steppe forced a portion of Alans previously living there to move northwest into the land of Venedes, possibly merging with Western Balts there to become the precursors of historic Slav nations.[29]

It's believed that some Alans resettled to the North (Barsils), merging with Volga Bulgars and Burtas, eventually transforming to Volga Tatars.[30]

It is supposed that Iasi, a group of Alans have founded a town in NE of Romania (about 1200–1300), called Iași near Prut river. Iași became the capital of ancient Moldova in Middle Ages.[31]

Medieval Alania

Some of the other Alans remained under the rule of the Huns. Those of the eastern division, though dispersed about the steppes until late medieval times, were forced by the Mongols into the Caucasus, where they remain as the Ossetians. Between the 9th and 12th centuries, they formed a network of tribal alliances that gradually evolved into the Christian kingdom of Alania. Most Alans submitted to the Mongol Empire in 1239–1277. They participated in Mongol invasions of Europe and the Song Dynasty in Southern China, and the Battle of Kulikovo under Mamai of the Golden Horde.[32]

In 1253, the Franciscan monk William of Rubruck reported numerous Europeans in Central Asia. It is also known that 30,000 Alans formed the royal guard (Asud) of the Yuan court in Dadu (Beijing). Marco Polo later reported their role in the Yuan Dynasty in his book Il Milione. It's said that those Alans contributed to a modern Mongol clan, Asud. John of Montecorvino, archbishop of Dadu (Khanbaliq), reportedly converted many Alans to Roman Catholic Christianity.[33][34] In Poland and Lithuania, Alans where also part of powerful Clan of Ostoja.

Religion, language, and later history

The ancient language of the Alans was a Northeastern-Iranian dialect either identical, or at least closely related, to Proto-Ossetic, which is confirmed by evidence left by John Tzetzes, a Byzantine poet and grammarian who lived at Constantinople during the 12th century and who was related to Maria of Alania. Tzetzes gave a few sentences in the Alanic language, along with Greek translation, in his ‘Theogony’, and most of the words in the sample have modern Ossetic conterparts including the greeting “Da ban xas” (“Good day”) known from the Jász word list of 1422 as well (“Da ban horz”, and comparable to the Digoron “Da bōn xwārz” and Iron “Da bōn xōrz”, the most common Ossetic greetings to this day. Most linguists regard the language of Tzetze’s sample as Proto-Ossetic.

In the 4th–5th centuries the Alans were at least partially Christianized by Byzantine missionaries of the Arian church. In the 13th century, fresh invading Mongol hordes pushed the eastern Alans further south into the Caucasus, where they mixed with native Caucasian groups and successively formed three territorial entities each with different developments. Around 1395 Timur's army invaded Northern Caucasus and massacred much of the Alanian population.

As the time went by, Digor in the west came under Kabard and Islamic influence. It was through the Kabardians (an East Circassian tribe) that Islam was introduced into the region in the 17th century. After 1767, all of Alania came under Russian rule, which strengthened Orthodox Christianity in that region considerably. Vast majority of today's Ossetians are followers of traditional Ossetian religion.

The descendants of the Alans, who live in the autonomous republics of Russia and Georgia, speak the Ossetian language which belongs to the Northeastern Iranian language group and is the only remnant of the Scytho-Sarmatian dialect continuum, which once stretched over much of the Pontic steppe and Central Asia. Modern Ossetian has two major dialects: Digor, spoken in the western part of North Ossetia; and Iron, spoken in the rest of Ossetia. A third branch of Ossetian, Jassic (Jász), was formerly spoken in Hungary. The literary language, based on the Iron dialect, was fixed by the national poet, Kosta Khetagurov (1859–1906).

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Alani". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Spain: Visigothic Spain to c. 500". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Vandal". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Encyclopedia Iranica, "Alans" V. I. Abaev External link

- ↑ Agustí Alemany, Sources on the Alans: A Critical Compilation. Brill Academic Publishers, 2000 ISBN 90-04-11442-4

- ↑ For ethnogenesis, see Walter Pohl, "Conceptions of Ethnicity in Early Medieval Studies" Debating the Middle Ages: Issues and Readings, ed. Lester K. Little and Barbara H. Rosenwein, (Blackwell), 1998, pp 13–24) (On-line text).

- ↑ The Hou Hanshu

- ↑ The Weilüe

- ↑ Kozin, S.A., Sokrovennoe skazanie, M.-L., 1941. p.83-4

- ↑ Alemany p. 3

- ↑ Alemany pp. 5–7

- ↑ See Agustí Alemany, Sources on the Alans Handbook of Oriental Studies, sect. 8, vol 5) (Leiden:Brill) 2000.

- ↑ The Chinese li of the Han period differs from the modern SI base unit of length; one li was equivalent to 415.8 metres.

- ↑ Perhaps what is known in the sources as the Northern Sea". The "Great Shoreless lake" probably referred to both the Aral and Caspian seas. Source in Watson, Burton trans. 1993. Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian. Han Dynasty II. (Revised Edition), p. 234. Columbia University Press. New York. ISBN 0-231-08166-9; ISBN 0-231-08167-7 (pbk.)

- ↑ Hill, John E. 2003. "Annotated Translation of the Chapter on the Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu." Revised Edition – to be published soon.

- ↑ For an earlier version of this translation

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus. Roman History. Book XXXI. II. 12

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus. Roman History. Book XXXI. II. 21. "Proceri autem Halani paene sunt omnes et pulchri, crinibus mediocriter flavis, oculorum temperata torvitate terribiles et armorum levitate veloces."

- ↑ Vologeses inscription.

- ↑ Vegetius 3.26, noted in passing by T.D. Barnes, "The Date of Vegetius" Phoenix 33.3 (Autumn 1979, pp. 254–257) p. 256. "The collocation of these three barbarian races does not recur a generation later", Barnes notes, in presenting a case for a late 4th-century origin for Vegetius' treatise.

- ↑ Giovanni de Marignolli, "John De' Marignolli and His Recollections of Eastern Travel", in Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Volume 2, ed. Henry Yule (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1866), 316–317.

- ↑ Isaac Newton, Observations on Daniel and The Apocalypse of St. John (1733).

- ↑ Paul the Deacon, Historia Romana, XV, 1.

- ↑ Bernard S. Bachrach, "The Origin of Armorican Chivalry" Technology and Culture 10.2 (April 1969), pp. 166–171.

- ↑ Bernard S. Bachrach, "The Alans in Gaul", Traditio 23 (1967).

- ↑ For another rapid disintegration of an ethne in the Early Middle Ages, see Avars. (Pohl 1998:17f).

- ↑ Milhazes, José. Os antepassados caucasianos dos portugueses – Rádio e Televisão de Portugal in Portuguese.

- ↑ Ivo Xavier Fernándes. Topónimos e gentílicos, Volume 1, 1941, p. 144.

- ↑ Ioachimi Pastorii Florus Polonicus, seu Poloniae historiae epitome nova, Lugduni Batavorum (Leiden), 1641 (see in the Preface).

- ↑ (Russian) Тайная история татар

- ↑ A. Boldur, Istoria Basarabiei, p. 20

- ↑ Handbuch Der Orientalistik By Agustí Alemany, Denis Sinor, Bertold Spuler, Hartwig Altenmüller, p. 400–410

- ↑ Roux, p.465

- ↑ Christian Europe and Mongol Asia: First Medieval Intercultural Contact Between East and West

See also

- Migrations period

- Burtas

- Sarmatians

- Scythians

- Ossetians

- Clan of Ostoja

References

- Agustí Alemany, Sources on the Alans: A Critical Compilation. Brill Academic Publishers, 2000 ISBN 90-04-11442-4

- Bernard S. Bachrach, A History of the Alans in the West, from their first appearance in the sources of classical antiquity through the early Middle Ages, University of Minnesota Press, 1973 ISBN 0-8166-0678-1

- Bachrach, Bernard S. "The Origin of Armorican Chivalry." Technology and Culture, Vol. 10, No. 2. (Apr., 1969), pp. 166–171.

- Castritius, H. 2007. Die Vandalen. Kohlhammer Urban.

- Golb, Norman and Omeljan Pritsak, Khazarian Hebrew Documents of the Tenth Century. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1982.

- Hill, John E. 2003. "Annotated Translation of the Chapter on the Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu." 2nd Draft Edition.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Yu, Taishan. 2004. A History of the Relationships between the Western and Eastern Han, Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties and the Western Regions. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 131 March 2004. Dept. of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania.