Ajtony

Ajtony, also Ahtum or Achtum (Bulgarian: Охтум, Hungarian: Ajtony, Romanian: Ahtum, Serbian: Ахтум), was a ruler in the territory now known as Banat (in present-day Romania and Serbia) in the first decades of the 11th century. The main source of his life is the longer version of the Life of St Gerard, a 14th-century hagiography. Ajtony was a powerful ruler who owned innumerable horses, cattle and sheep. He was baptised according to the Orthodox rite in Vidin. Ajtony levied tax on the salt transferred to King Stephen I of Hungary on the Mureș River. The king sent Csanád, who had been the commander-in-chief of Ajtony's army, against Ajtony at the head of a large army. Csanád defeated and killed Ajtony and occupied his realm. In the same territory, at least one county and a Roman Catholic diocese were established.

Historians have not agreed the exact date of Ajtony's defeat: it may have occurred in 1002 or 1008 or between 1027 and 1030. Ajtony's ethinicity is also subject to debates among historians: he may have been Hungarian, Kabar, Pecheneg or Romanian. In Romanian historiography, he is regarded as the last member of a Romanian ruling family founded by Glad, who had been the lord of Banat around 900, according the Gesta Hungarorum, a chronicle of debated credibility.

Background

The Magyars, or Hungarians, who had dwelled in the Pontic steppes for decades, invaded the Carpathian Basin after a coalition of Bulgarians and Pechenegs defeated them around 895.[1][2] The Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus wrote that the seven Magyar tribes formed a confederation together with the Kabars.[3] The latter had originally lived within the Khazar Khaganate but rebelled against the Khazars and joined the Magyars in the Pontic steppes.[4]

According to Regino of Prüm, Constantine Porphyrogenitus and other contemporaneous sources, the Magyars fought against the Bavarians, Bulgarians, Carinthians, Franks, and Moravians.[2][5] Among the conquering Magyars' opponents, the same sources mentioned many local rulers, including Svatopluk I of Moravia, Luitpold of Bavaria, and Braslav, Duke of Lower Pannonia.[6][7] Instead of these people, the Gesta Hungarorum—the earliest extant Hungarian chronicle which was written after 1150[8][9]—wrote of Glad, the lord of the lands between the rivers Danube and Mureș (now known as Banat in Romania and Serbia) and other local rulers who had not been mentioned in earlier primary sources.[5][6][7] Accordingly, the credibility of the reports of the Gesta of these rulers is subject to scholarly debates.[10] For instance, Vlad Georgescu, Ioan Aurel Pop and other historians present Glad as one of the local Romanian rulers who attempted to resist the invading Hungarians,[10][11][12] while other scholars—including Pál Engel and György Györffy—write that Glad is one of the dozen "imaginary figures" invented by Anonymus, the author of the Gesta, who had to create enemies for the conquerors because he had no information of the exact circumstances of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin.[6][13]

Constantine Porphyrogenitus identified "the whole settlement of Turkey" (that is Hungary) with the regions of five rivers—Criș, Mureș, Timiș, Tisza, and the unidentified "Toutis"[14]—around 950, showing that the lands east of the Tisza were controlled by the Hungarians around 950.[15][16] The emperor seems to have received information of the situation in the Carpathian Basin from Termatzus, Bulcsú and Gylas, three Hungarian chieftains who visited Constantinople in the mid-10th century.[17][18] Bulcsú and Gylas were baptised during their visit, according to the Byzantine historian John Skylitzes.[18][19] Bulcsú, Skylitzes continued, "violated his contract with God and often invaded" the Byzantine Empire even thereafter, but Gylas "remained faithful to Christianity",[20] making no further inroads against the empire.[18][19] One Hierotheos who was consencrated bishop for the Hungarians accompanied Gylas to his land where he "converted many from the barbaric fallacy to Christianity",[20] according to Skylitzes.[21][22] Most 10th-century Byzantine coins, pectoral crosses and other artifacts have been unearthed in the wider region of the confluence of the rivers Tisza and Mureș, especially in the Banat.[23][24] Accordingly, Tudor Sălăgean, Florin Curta and other historians say that the lands subjected to Gylas's rule must have been located in these territories, but their theory have not been universally accepted.[21][23][24]

In contrast with Gylas, who opted for the Eastern Orthodox form of Christianity, Géza, Grand Prince of the Hungarians preferred the Western Church.[25] A cleric who came from the Holy Roman Empire (according to most scholars, one Bruno from the Abbey of Saint Gall) baptised him in the 970s.[26][27] Thietmar of Merseburg and other 11th-century authors emphasized that Géza had been a cruel ruler, suggesting that the unification of the Hungarian chieftains' lands began under his rule.[27][28] Géza was succeeded by his son, Stephen, who was crowned the first king of Hungary in 1000 or 1001.[27]

Ajtony in the primary sources

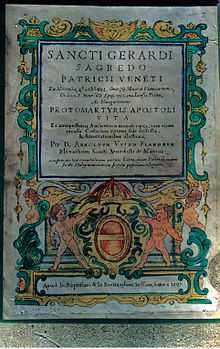

The principal source of Ajtony's life is the longer version of the Life of St Gerard, which was compiled from a variety of earlier sources in the early 14th century.[29][30] According to modern historians (including Carlile Aylmer Macartney and Florin Curta), all information on Ajtony was incorporated in the Life based on a ballad of the heroic deeds of Csanád, Ajtony's former commander-in-chief, because the shorter version of Bishop St Gerard's legend does not refer to Ajtony.[29][31] Most historians agree that this ballad was composed shortly after Ajtony's dead.[29][31] In addition of the Life of St Gerard, Ajtony is also mentioned in the Gesta Hungarorum,[32] a Hungarian chronicle completed after around 1150.[33] The Gesta Hungarorum said that Ajtony had descended from Glad who, according to the same source, was the lord of Banat, but the credibility of this report is debated.[34][30][35][36] According to a sermon of 1499 of the Franciscan Osvát Laskai,[30] Ajtony hailed from the Nyírség region, but nothing proves that the author had actual knowledge of Ajtony's place of birth.[37]

Ajtony's name which was in the earliest sources recorded as Ohtun or Achtum is of Turkic origin.[38][39] The root of the name is the Turkic word for golden (altun) which transformed in the Hungarian language, according to the linguist Loránd Benkő.[38][39] Place names also reflect the name Ajtony: an abbey named Ahtunmonustura ("Ajtony's monastery") existed in Csanád County and a village named Ahthon in Krassó County, and the settlement Aiton still exists in Romania.[40][41][42]

Ajtony was a powerful prince who had his seat in a stronghold on the Mureș (urbs Morisena), according to the Life of St Gerard.[43][30][44] His realm stretched from the Criș in the north to the Danube in the south, and from the Tisza in the west to Transylvania in the east.[44][45] He was a wealthy ruler who owned horses, cattle and sheep.[45][46] He commanded so many warriors that he did not fear of setting up custom offices and guards along the Mureș and levying tax on the salt carried to Stephen I of Hungary on the river.[45][47]

Although originally a pagan, Ajtony was baptised according to the "Greek rite" in Vidin.[48][49] Ajtony established a monastery for Greek monks in his seat and dedicated it to St John the Baptist shortly after his baptism.[49] However, he remained polygamic and had seven wives even after his baptism.[50][46] St Gerard's legend also stated that Ajtony "had taken his power from the Greeks",[49] suggesting that he accepted the Byzantine Emperor's suzerainty.[51]

The commander-in-chief of Ajtony's army was Csanád, whom the Gesta Hungarorum described as the "son of Doboka and nephew"[52] of King Stephen.[53][45] Csanád who was accused of conspiring against Ajtony deserted his master and fled to the king.[45] The king decided to conquest Ajtony's realm.[45] He sent Csanád at the head of a large army against Ajtony.[54] Having crossed the Tisza, the royal army joined battle with Ajtony's troops, but was forced to withdraw.[45] However, in a second battle, the royal army routed Ajtony's troops near modern Banatsko Aranđelovo or Tomnatic.[39][45] Csanád killed Ajtony in the battlefield (as the Life of St Gerard stated it) or in his stronghold on the Mureș (according to the Gesta Hungarorum).[55] According to a legendary episode preserved in the Life of St Gerard, Csanád cut out the dead Ajtony's tongue which enabled him to prove that he had killed Ajtony instead of one Gyula who boasted about this deed in the presence of the king.[55] Archaeologist István Erdélyi writes that the Treasure of Sânnicolau Mare, which was unearthed near Ajtony's one-time seat, was connected to Ajtony, but his view has not been universally accepted by scholars.[38][56]

King Stephen granted large estates to Csanád in the lands that had been subjected to Ajtony's rule.[29] Ajtony's stronghold, which is now known as Cenad (in Hungarian, Csanád), was named after the commander of the royal army.[57] The king also appointed Csanád the head, or ispán, of the county which was organized in Ajtony's former realm.[53] King Stephen established a Roman Catholic diocese in Cenad.[58] The Venetian monk Gerard was appointed the first bishop of this diocese.[56] The Greek monks from Cenad were transferred to a new monastery that Csanád built at Banatsko Aranđelovo.[59] On the other hand, families who were descended from the Ajtony kindred held landed estates in the region, proving that King Stephen had not confiscated Ajtony's all domains.[56]

Ajtony in modern historiography

Ajtony's ethnicity is a controversial issue.[29] For instance, historian Paul Stephenson writes that Ajtony was a Magyar chieftain,[48] László Makkai says that he was of Kabar origin,[55] and his Turkic name may imply that he was of Pecheneg stock.[42] In Romanian historiography, Ajtony has been regarded as the last member of a Romanian dynasty descending from Glad.[60] For instance, Alexandru Madgearu writes that the Latin name of Ajtony's seat (urbs Morisena) preserved a Romanian form.[61] Ioan Aurel Pop even says that Ajtony's former duchy was only fully incorporated in the Kingdom of Hungary in the 13th century because the frequent internal conflicts had ennabled the Romanians to preserve their idea of a "Romanian country".[62]

The date of the conquest of Ajtony's realm is also subject to scholarly debates.[29] His close contacts with the Byzantine Empire, including his baptism according to the "Greek rite" in Vidin, shows that Ajtony ruled even after the Byzantine Emperor Basil II seized Vidin from the Bulgarians in 1002.[48][63] On the other hand, the conflict between Ajtony and King Stephen must have occurred before the king appointed Gerard the first bishop of Csanád in 1030.[29] Alexandru Madgearu, who also says that Ajtony was an ally of Samuel of Bulgaria instead of the Emperor Basil II, writes that Stephen I's army occupied Ajtony's realm in parallel with Basil II's conquest of Vidin in 1002.[64] László Makkai says that the conquest of Ajtony's realm occurred in 1008.[55] According to Ioan Aurel Pop, Stephen I only decided to invade Banat after a Pecheneg raid into the Byzantine Empire in 1027 and the death of Emperor Constantine VIII in 1028.[65] Finally, Florin Curta rejects the whole episode of Ajtony in the Life of St Gerard, saying that it was only a "family legend" in a 14th-century hagiographic work.[60][51]

See also

References

- ↑ Stephenson 2000, p. 39.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 76-77.

- ↑ Stephenson 2000, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 72.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Deletant 1992, pp. 73-74.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Engel 2001, p. 11.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Györffy 1988, p. 39.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005, pp. 15-20.

- ↑ Pop 1996, p. 97.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Deletant 1992, p. 85.

- ↑ Georgescu 1991, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Pop 1996, pp. 96-97, 102-103.

- ↑ Györffy 1988, pp. 84-86.

- ↑ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 40), pp. 177-179.

- ↑ Tóth 1999, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Stephenson 2000, p. 41.

- ↑ Tóth 1999, p. 30.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Curta 2006, pp. 189-190.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 129-130.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 John Skylitzes: A Synopsis of Byzantine History, 811-1057 (ch. 9.5), p.231.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Sălăgean 2005, p. 147.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 24.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Curta 2006, p. 196.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 130.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 131.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 137.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Engel 2001, p. 26.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 132.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 Curta 2001, p. 142.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Pop 1996, p. 130.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Macartney 1953, p. 158.

- ↑ Curta 2001, p. 143.

- ↑ Pop 1996, pp. 76, 129-130.

- ↑ Curta 2001, pp. 144-145.

- ↑ Macartney 1953, p. 79.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 79.

- ↑ Györffy 2000, p. 164.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Hosszú 2012, p. 125.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Szegfű 1994, p. 32.

- ↑ Györffy 1987a, p. 846.

- ↑ Györffy 1987b, pp. 341, 471.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Pop 1996, p. 139.

- ↑ Pop 1996, pp. 130-131.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Sălăgean 2005, p. 148.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 45.6 45.7 Pop 1996, p. 131.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Engel 2001, p. 41.

- ↑ Curta 2001, p. 250.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Stephenson 2000, p. 65.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Curta 2006, p. 248.

- ↑ Bóna 1994, p. 127.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 149.

- ↑ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 11.), p. 33.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Szegfű 1994, p. 145.

- ↑ Curta 2006, p. 250.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 Makkai, László (2001). "Transylvania in the medieval Hungarian kingdom (896-1526); From the Hungarian Conquest to the Mongol invasion; White and Black Hungarians". Columbia University Press. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Szegfű 1994, p. 33.

- ↑ Pop 1996, p. 132.

- ↑ Sălăgean 2005, p. 149.

- ↑ Bóna 1994, pp. 127-128.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Curta 2001, p. 144.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005, p. 143.

- ↑ Pop 1996, p. 140.

- ↑ Curta 2001, pp. 142-144.

- ↑ Madgearu 2005, p. 35.

- ↑ Pop 1996, pp. 137-138.

Sources

Primary sources

- Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited, Translated and Annotated by Martyn Rady and László Veszprémy) (2010). In: Rady, Martyn; Veszprémy, László; Bak, János M. (2010); Anonymus and Master Roger; CEU Press; ISBN 978-963-9776-95-1.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (Greek text edited by Gyula Moravcsik, English translation b Romillyi J. H. Jenkins) (1967). Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5.

- John Skylitzes: A Synopsis of Byzantine History, 811-1057 (Translated by John Wortley with Introductions by Jean-Claude Cheynet and Bernad Flusin and Notes by Jean-Claude Cheynet) (2010). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76705-7.

Secondary sources

- Berend, Nora; Urbańczyk, Przemysław; Wiszewski, Przemysław (2013). Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c. 900-c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78156-5.

- Bóna, István (1994). "The Hungarian–Slav Period (895–1172)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit. History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 109–177. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

- Curta, Florin (2001). "Transylvania around A.D. 1000". In Urbańczyk, Przemysław. Europe around the year 1000. Wydawn. DiG. pp. 141–165. ISBN 978-837-1-8121-18.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

- Deletant, Dennis (1992). "Ethnos and Mythos in the History of Transylvania: the case of the chronicler Anonymus". In Péter, László. Historians and the History of Transylvania. Boulder. pp. 67–85. ISBN 0-88033-229-8.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991). The Romanians: A History. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0511-9.

- Györffy, György (1987a). Az Árpád-kori Magyarország történeti földrajza, I: Abaújvár, Arad, Árva, Bács, Baranya, Bars, Békés, Bereg, Beszterce, Bihar, Bodrog, Borsod, Brassó, Csanád és Csongrád megye [Historical Geography of Hungary of the Árpáds, Volume I: The Counties of Abaújvár, Arad, Árva, Bács, Baranya, Bars, Békés, Bereg, Beszterce, Bihar, Bodrog, Borsod, Brassó, Csanád and Csongrád] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-4200-5.

- Györffy, György (1987b). Az Árpád-kori Magyarország történeti földrajza, III: Heves, Hont, Hunyad, Keve, Kolozs, Komárom, Krassó, Kraszna, Küküllő megye és Kunság [Historical Geography of Hungary of the Árpáds, Volume III: The Counties of Heves, Hont, Hunyad, Keve, Kolozs, Komárom, Krassó, Kraszna and Küküllő, and Cumania] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-3613-7.

- Györffy, György (1988). Anonymus: Rejtély vagy történeti forrás [Anonymous: An Enigma or a Source for History] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-4868-2.

- Györffy, György (2000). István király és műve [King Stephen and His Work] (in Hungarian). Balassi Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-5-06382-6.

- Hosszú, Gábor (2012). Heritage of Scribes: The Relation of Rovas Scripts to Eurasian Writing Systems. Rovas Foundation. ISBN 978-963-88-4374-6.

- Macartney, C. A. (1953). The Medieval Hungarian Historians: A Critical & Analytical Guide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08051-4.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2005). The Romanians in the Anonymous Gesta Hungarorum: Truth and Fiction. Romanian Cultural Institute, Center for Transylvanian Studies. ISBN 973-7784-01-4.

- Pop, Ioan Aurel (1996). Romanians and Hungarians from the 9th to the 14th Century: The Genesis of the Transylvanian Medieval State. Centrul de Studii Transilvane, Fundaţia Culturală Română. ISBN 973-577-037-7.

- Sălăgean, Tudor (2005). "Romanian Society in the Early Middle Ages (9th–14th Centuries AD)". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan. History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). pp. 133–207. ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.

- Stephenson, Paul (2000). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02756-4.

- Szegfű, László (1994). "Ajtony; Csanád". In Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc. Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th centuries)] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 32–33, 145. ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

- Tóth, Sándor László (1999). "The territories of the Hungarian tribal federation around 950 (Some observations on Constantine VII's "Tourkia")". In Prinzing, Günter; Salamon, Maciej. Byzanz und Ostmitteleuropa 950-1453: Beiträge zu einer table-ronde des XIX. International Congress of Byzantine Studies, Copenhagen 1996 [Byzantium and East Central Europe 950-1453: Contributions to a Round-table Discussion of the 19th International Congress of Byzantine Studies, Copenhagen 1996]. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 22–34. ISBN 3-447-04146-3.

Further reading

- Klepper, Nicolae (2005). Romania: An Illustrated History. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-7818-0935-5.

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2005). "Salt Trade and Warfare: The Rise of Romanian-Slavic Military Organization in Early Medieval Transylvania". In Curta, Florin. East Central & Eastern Europe in the Early Middle Ages. The University of Michigan Press. pp. 103–120. ISBN 978-0-472-11498-6.

- Pop, Ioan Aurel (1999). Romanians and Romania: A Brief History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-88033-440-1.