Aichelburg–Sexl ultraboost

In general relativity, the Aichelburg–Sexl ultraboost is an exact solution which models the physical experience of an observer moving past a spherically symmetric gravitating object at nearly the speed of light. It was introduced by Peter C. Aichelburg and Roman U. Sexl in 1971.

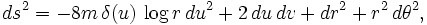

The metric tensor can be written, in terms of Brinkmann coordinates, as

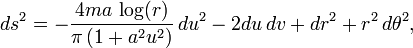

The ultraboost can be obtained as the limit of various sequences of smooth Lorentzian manifolds. For example, we can take Poor-man's Gaussian pulses

In these plus-polarized axisymmetric vacuum pp-waves, the curvature is concentrated along the axis of symmetry, falling off like O(m/r), and also near  . As

. As  , the wave profile turns into a Dirac delta, and we recover the ultraboost. (To avoid possible misunderstanding, we stress that these are exact solutions which approximate the ultraboost, which is also an exact solution, at least if you admit impulsive curvatures.)

, the wave profile turns into a Dirac delta, and we recover the ultraboost. (To avoid possible misunderstanding, we stress that these are exact solutions which approximate the ultraboost, which is also an exact solution, at least if you admit impulsive curvatures.)

This resolves the following paradox: The moving particle will "think" that the stationary object (let's use a planet) has a huge mass, because in the particle's point of view the planet is moving at an ultra relativistic speed. What if the particle moves fast enough so that the planet becomes a black hole, and the particle gets inside the event horizon? Why does it fly right past (like a photon) and not get trapped?

References

- Frolov, Valeri P.; & Novikov, Igor D. (1998). Black Hole Physics. Boston: Klüwer. ISBN 0-7923-5146-0. See Section 7.6.12

- Poldolský, J.; & Griffiths, J. B. (1998). "Boosted static multipole particles as sources of impulsive gravitational waves". Phys. Rev. D 58: 124024. arXiv:gr-qc/9809003. Bibcode:1998PhRvD..58l4024P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.58.124024.

- Aichelburg, P. C.; & Sexl, R. U. (1971). "On the gravitational field of a massless particle". Gen. Rel. Grav. 2: 303. Bibcode:1971GReGr...2..303A. doi:10.1007/BF00758149.