Afghanistan

| Islamic Republic of Afghanistan

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: There is no god but God, Muhammad is the messenger of God | ||||||

| Anthem: "Afghan National Anthem" |

||||||

.svg.png) |

||||||

_-_AFG_-_UNOCHA.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Kabul 34°32′N 69°08′E / 34.533°N 69.133°E | |||||

| Official languages | [1] | |||||

| Religion | Islam | |||||

| Demonym | Afghan [alternatives] | |||||

| Government | Presidential republic | |||||

| - | President | Ashraf Ghani | ||||

| - | Chief Executive Officer | Abdullah Abdullah | ||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||

| - | Upper house | Mesherano Jirga | ||||

| - | Lower house | Wolesi Jirga | ||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| - | First Afghan state | April 1709 | ||||

| - | Afghan Empire | October 1747 | ||||

| - | Recognized | 19 August 1919 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 652,864[2] km2 (41st) 251,827 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | negligible | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2014 estimate | 31,822,848[3] (40th) | ||||

| - | 1979 census | 15.5 million[4] | ||||

| - | Density | 43.5/km2 (150th) 111.8/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2014 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $36.838 billion[5] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $1,177[5] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2014 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $21.747 billion[5] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $695[5] | ||||

| Gini (2008) | 29[6] low |

|||||

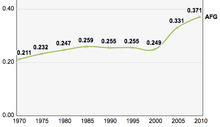

| HDI (2013) | low · 169th |

|||||

| Currency | Afghani (AFN) | |||||

| Time zone | D† (UTC+4:30) | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +93 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | AF | |||||

| Internet TLD | .af افغانستان. | |||||

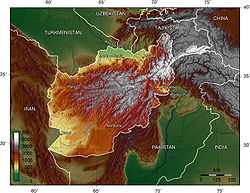

Afghanistan ![]() i/æfˈɡænɨstæn/ (Pashto/Dari: افغانستان, Afġānistān), officially the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located within South Asia and Central Asia.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15] It has a population of approximately 31 million people, making it the 42nd most populous country in the world. It is bordered by Pakistan in the south and east; Iran in the west; Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan in the north; and China in the far northeast. Its territory covers 652,000 km2 (252,000 sq mi), making it the 41st largest country in the world.

i/æfˈɡænɨstæn/ (Pashto/Dari: افغانستان, Afġānistān), officially the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located within South Asia and Central Asia.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15] It has a population of approximately 31 million people, making it the 42nd most populous country in the world. It is bordered by Pakistan in the south and east; Iran in the west; Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan in the north; and China in the far northeast. Its territory covers 652,000 km2 (252,000 sq mi), making it the 41st largest country in the world.

Human habitation in Afghanistan dates back to the Middle Paleolithic Era,[16] and the country's strategic location along the Silk Road connected it to the cultures of the Middle East and other parts of Asia.[17] Through the ages the land has been home to various peoples[18] and witnessed numerous military campaigns, notably by Alexander the Great, Muslim Arabs, Mongols, British, Soviet Russians, and in the modern-era by Western powers.[16] The land also served as the source from which the Kushans, Hephthalites, Samanids, Saffarids, Ghaznavids, Ghorids, Khiljis, Mughals, Hotaks, Durranis, and others have risen to form major empires.[19]

The political history of the modern state of Afghanistan began with the Hotak and Durrani dynasties in the 18th century.[20][21][22] In the late 19th century, Afghanistan became a buffer state in the "Great Game" between British India and the Russian Empire. Following the 1919 Anglo-Afghan War, King Amanullah and King Mohammed Zahir Shah attempted modernization of the country. A series of coups in the 1970s was followed by a Soviet invasion and a series of civil wars that devastated much of the country.

Etymology

The name Afghānistān (Persian: افغانستان, [avɣɒnestɒn]) is believed to be as old as the ethnonym Afghan, which is documented in the 10th-century geography book Hudud ul-'alam.[23] The word Afghan comes from the Sanskrit word Avgana; probably deriving from Aśvaka.[24][25] The root name "Afghan" was used historically as a reference to the Pashtun people,[26] and the suffix "-stan" means "place of" in Persian language. Therefore, Afghanistan translates to "land of the Afghans".[27][28] The Constitution of Afghanistan states that "[t]he word Afghan shall apply to every citizen of Afghanistan."[29]

History

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Afghanistan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Excavations of prehistoric sites by Louis Dupree and others suggest that humans were living in what is now Afghanistan at least 50,000 years ago, and that farming communities in the area were among the earliest in the world.[30][31] An important site of early historical activities, many believe that Afghanistan compares to Egypt in terms of the historical value of its archaeological sites.[32]

The country sits at a unique nexus point where numerous civilizations have interacted and often fought. It has been home to various peoples through the ages, among them the ancient Iranian peoples who established the dominant role of Indo-Iranian languages in the region. At multiple points, the land has been incorporated within large regional empires, among them the Achaemenid Empire, the Macedonian Empire, the Indian Maurya Empire, and the Islamic Empire.[33]

Many kingdoms have also risen to power in Afghanistan, such as the Greco-Bactrians, Kushans, Hephthalites, Kabul Shahis, Saffarids, Samanids, Ghaznavids, Ghurids, Khiljis, Kartids, Timurids, Mughals, and finally the Hotak and Durrani dynasties that marked the political origins of the modern state.[34]

Pre-Islamic period

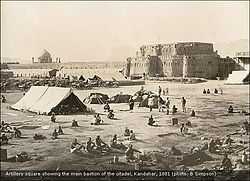

Archaeological exploration done in the 20th century suggests that the geographical area of Afghanistan has been closely connected by culture and trade with its neighbors to the east, west, and north. Artifacts typical of the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron ages have been found in Afghanistan.[35] Urban civilization is believed to have begun as early as 3000 BCE, and the early city of Mundigak (near Kandahar in the south of the country) may have been a colony of the nearby Indus Valley Civilization.[31]

After 2000 BCE, successive waves of semi-nomadic people from Central Asia began moving south into Afghanistan; among them were many Indo-European-speaking Indo-Iranians.[30] These tribes later migrated further south to India, west to what is now Iran, and towards Europe via the area north of the Caspian Sea.[36] The region as a whole was called Ariana.[30][37][38]

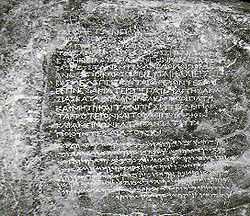

The people shared similar culture with other Indo-Iranians. The ancient religion of Kafiristan survived here until the 19th century. Another religion, Zoroastrianism is believed by some to have originated in what is now Afghanistan between 1800 and 800 BCE, as its founder Zoroaster is thought to have lived and died in Balkh.[39][40][41] Ancient Eastern Iranian languages may have been spoken in the region around the time of the rise of Zoroastrianism. By the middle of the 6th century BCE, the Achaemenid Persians overthrew the Medes and incorporated Arachosia, Aria, and Bactria within its eastern boundaries. An inscription on the tombstone of King Darius I of Persia mentions the Kabul Valley in a list of the 29 countries that he had conquered.[42]

Alexander the Great and his Macedonian forces arrived to Afghanistan in 330 BCE after defeating Darius III of Persia a year earlier in the Battle of Gaugamela.[39] Following Alexander's brief occupation, the successor state of the Seleucid Empire controlled the region as one of their easternmost territories until 305 BCE, when they gave much of it to the Indian Maurya Empire as part of an alliance treaty. The Mauryans introduced Buddhism and controlled the area south of the Hindu Kush until they were overthrown about 185 BCE.[43] Their decline began 60 years after Ashoka's rule ended, leading to the Hellenistic reconquest of the region by the Greco-Bactrians. Much of it soon broke away from the Greco-Bactrians and became part of the Indo-Greek Kingdom. The Indo-Greeks were defeated and expelled by the Indo-Scythians in the late 2nd century BCE.[44]

During the first century BCE, the Parthian Empire subjugated the region, but lost it to their Indo-Parthian vassals. In the mid-to-late first century CE the vast Kushan Empire, centered in modern Afghanistan, became great patrons of Buddhist culture, making Buddhism flourish throughout the region. The Kushans were defeated by the Sassanids in the 3rd century CE. Although the Indo-Sassanids continued to rule at least parts of the region.[45] They were followed by the Kidarite Huns[46] who, in turn, were replaced by the Hephthalites.[47] By the 6th century CE, the successors to the Kushans and Hepthalites established a small dynasty called Kabul Shahi.

Islamization and Mongol invasion

Before the 19th century, the northwestern area of Afghanistan was referred to by the regional name Khorasan.[48][49] Two of the four capitals of Khorasan (Herat and Balkh[50]) are now located in Afghanistan, while the regions of Kandahar, Zabulistan, Ghazni, Kabulistan, and Afghanistan formed the frontier between Khorasan and Hindustan.[50][51][52]

Arab Muslims brought Islam to Herat and Zaranj in 642 CE and began spreading eastward; some of the native inhabitants they encountered accepted it while others revolted.[53] The land was collectively recognized by the Arabs as al-Hind due to its cultural connection with Greater India. Before Islam was introduced, people of the region were multi-religious, including Zoroastrians, Buddhists, Surya and Nana worshipers, Jews, and others.[54] The Zunbils and Kabul Shahi were first conquered in 870 CE by the Saffarid Muslims of Zaranj. Later, the Samanids extended their Islamic influence south of the Hindu Kush. It is reported that Muslims and non-Muslims still lived side by side in Kabul before the Ghaznavids rose to power in the 10th century.[55]

Afghanistan became one of the main centers in the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age.[30][56] By the 11th century, Mahmud of Ghazni defeated the remaining Hindu rulers and effectively Islamized the wider region, with the exception of Kafiristan. The Ghaznavid dynasty was defeated and replaced by the Ghurids, who expanded and advanced the already powerful Islamic empire. Some speculate that today's Nasher clan is a remnant of the Ghaznavid dynasty.[57][58][59]

In 1219 AD, Genghis Khan and his Mongol army overran the region. His troops are said to have annihilated the Khorasanian cities of Herat and Balkh as well as Bamyan.[60] The destruction caused by the Mongols forced many locals to return to an agrarian rural society.[61] Mongol rule continued with the Ilkhanate in the northwest while the Khilji dynasty administered the Afghan tribal areas south of the Hindu Kush until the invasion of Timur, who established the Timurid dynasty in 1370.[62] During the Ghaznavid, Ghurid, and Timurid eras, the region produced many fine Islamic architectural monuments and numerous scientific and literary works.

In the early 16th century, Babur arrived from Fergana and captured Kabul from the Arghun dynasty. From there he began dominating control of the central and eastern territories of Afghanistan. He remained in Kabulistan until 1526 when he invaded Delhi in India to replace the Lodi dynasty with the Mughal Empire. Between the 16th and 18th century, the Khanate of Bukhara, Safavids, and Mughals ruled parts of the territory.[63]

Hotak dynasty and Durrani Empire

In 1709, Mirwais Hotak, a Pashtun from Kandahar, successfully rebelled against the Persian Safavids. He overthrew and killed Gurgin Khan, and made Afghanistan independent.[64] Mirwais died of a natural cause in 1715 and was succeeded by his brother Abdul Aziz, who was soon killed by Mirwais' son Mahmud for treason. Mahmud led the Afghan army in 1722 to the Persian capital of Isfahan, captured the city after the Battle of Gulnabad and proclaimed himself King of Persia.[64] The Persians rejected Mahmud, and after the massacre of thousands of religious scholars, nobles, and members of the Safavid family, the Hotak dynasty was ousted from Persia by Nader Shah Afshar after the 1729 Battle of Damghan.[65]

In 1738, Nader Shah and his forces captured Kandahar, the last Hotak stronghold, from Shah Hussain Hotak, at which point the incarcerated 16-year-old Ahmad Shah Durrani was freed and made the commander of an Afghan regiment.[66] Soon after the Persian and Afghan forces invaded India. By 1747, the Afghans chose Durrani as their head of state.[67][68][69] Durrani and his Afghan army conquered much of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, the Khorasan and Kohistan provinces of Iran, and Delhi in India.[70] He defeated the Indian Maratha Empire, and one of his biggest victories was the 1761 Battle of Panipat.

In October 1772, Durrani died of a natural cause and was buried at a site now adjacent to the Shrine of the Cloak in Kandahar. He was succeeded by his son, Timur Shah, who transferred the capital of Afghanistan from Kandahar to Kabul in 1776. After Timur's death in 1793, the Durrani throne passed down to his son Zaman Shah, followed by Mahmud Shah, Shuja Shah and others.[71]

The Afghan Empire was under threat in the early 19th century by the Persians in the west and the British-backed Sikhs in the east. Fateh Khan, leader of the Barakzai tribe, had installed 21 of his brothers in positions of power throughout the empire. After his death, they rebelled and divided up the provinces of the empire between themselves. During this turbulent period, Afghanistan had many temporary rulers until Dost Mohammad Khan declared himself emir in 1826.[72] The Punjab region was lost to Ranjit Singh, who invaded Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and in 1834 captured the city of Peshawar.[73] In 1837, during the Battle of Jamrud near the Khyber Pass, Akbar Khan and the Afghan army killed Sikh Commander Hari Singh Nalwa.[74] By this time the British were advancing from the east and the first major conflict during the "Great Game" was initiated.[75]

Western influence

Following the 1842 defeat of the British-Indian forces and victory of the Afghans, the British established diplomatic relations with the Afghan government and withdrew all forces from the country. They returned during the Second Anglo-Afghan War in the late 1870s for about two years to assist Abdur Rahman Khan defeat Ayub Khan. The United Kingdom began to exercise a great deal of influence after this and even controlled the state's foreign policy. In 1893, Mortimer Durand made Amir Abdur Rahman Khan sign a controversial agreement in which the ethnic Pashtun and Baloch territories were divided by the Durand Line. This was a standard divide and rule policy of the British and would lead to strained relations, especially with the later new state of Pakistan.

After the Third Anglo-Afghan War and the signing of the Treaty of Rawalpindi in 1919, King Amanullah Khan declared Afghanistan a sovereign and fully independent state. He moved to end his country's traditional isolation by establishing diplomatic relations with the international community and, following a 1927–28 tour of Europe and Turkey, introduced several reforms intended to modernize his nation. A key force behind these reforms was Mahmud Tarzi, an ardent supporter of the education of women. He fought for Article 68 of Afghanistan's 1923 constitution, which made elementary education compulsory. The institution of slavery was abolished in 1923.[76]

Some of the reforms that were actually put in place, such as the abolition of the traditional burqa for women and the opening of a number of co-educational schools, quickly alienated many tribal and religious leaders. Faced with overwhelming armed opposition, Amanullah Khan was forced to abdicate in January 1929 after Kabul fell to rebel forces led by Habibullah Kalakani. Prince Mohammed Nadir Shah, Amanullah's cousin, in turn defeated and killed Kalakani in November 1929, and was declared King Nadir Shah. He abandoned the reforms of Amanullah Khan in favor of a more gradual approach to modernisation but was assassinated in 1933 by Abdul Khaliq, a Hazara school student.[77]

Mohammed Zahir Shah, Nadir Shah's 19-year-old son, succeeded to the throne and reigned from 1933 to 1973. Until 1946, Zahir Shah ruled with the assistance of his uncle, who held the post of Prime Minister and continued the policies of Nadir Shah. Another of Zahir Shah's uncles, Shah Mahmud Khan, became Prime Minister in 1946 and began an experiment allowing greater political freedom, but reversed the policy when it went further than he expected. He was replaced in 1953 by Mohammed Daoud Khan, the king's cousin and brother-in-law. Daoud Khan sought a closer relationship with the Soviet Union and a more distant one towards Pakistan. Afghanistan remained neutral and was neither a participant in World War II nor aligned with either power bloc in the Cold War. However, it was a beneficiary of the latter rivalry as both the Soviet Union and the United States vied for influence by building Afghanistan's main highways, airports, and other vital infrastructure. In 1973, while King Zahir Shah was on an official overseas visit, Daoud Khan launched a bloodless coup and became the first President of Afghanistan. In the meantime, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto got neighboring Pakistan involved in Afghanistan. Some experts suggest that Bhutto paved the way for the April 1978 Saur Revolution.[78]

Derek Gregory argued in his book The Colonial Present that the makings of a failed state in Afghanistan had its roots in Western imperialism. The great game between the European powers over what was then the British possession of India, lead England and Russia to require a buffer zone between their imperial interests. A state was literally carved out of nothing, much the same way as it was all throughout Africa. (Stephen Howe, p. 13) Different ethnic groups, different languages and different ways of life were enmeshed together into a single state with little consideration of the effects of such policies. In this context, the creation of Afghanistan (like many other small states created by the European powers) had little to do with self-determination as it was claimed, but over geopolitics. Isah Bowman, a renowned, American geographer, is said to have championed the notion of many small states within Eastern Europe, Latin America and Africa to increase imperial competition, thus weakening their respective power in relation to the United States. (Painter and Jeffrey Ch 9)

Marxist revolution and Soviet war

.jpg)

In April 1978, the communist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) seized power in Afghanistan in the Saur Revolution. Within months, opponents of the communist government launched an uprising in eastern Afghanistan that quickly expanded into a civil war waged by guerrilla mujahideen against government forces countrywide. The Pakistani government provided these rebels with covert training centers, while the Soviet Union sent thousands of military advisers to support the PDPA government.[79] Meanwhile, increasing friction between the competing factions of the PDPA — the dominant Khalq and the more moderate Parcham — resulted in the dismissal of Parchami cabinet members and the arrest of Parchami military officers under the pretext of a Parchami coup.

In September 1979, Nur Muhammad Taraki was assassinated in a coup within the PDPA orchestrated by fellow Khalq member Hafizullah Amin, who assumed the presidency. Distrusted by the Soviets, Amin was assassinated by Soviet special forces in December 1979. A Soviet-organized government, led by Parcham's Babrak Karmal but inclusive of both factions, filled the vacuum. Soviet troops were deployed to stabilize Afghanistan under Karmal in more substantial numbers, although the Soviet government did not expect to do most of the fighting in Afghanistan. As a result, however, the Soviets were now directly involved in what had been a domestic war in Afghanistan.[80] The PDPA prohibited usury, declared equality of the sexes,[81] and introducing women to political life.[81]

The United States has been supporting anti-Soviet forces (mujahideen) as early as mid-1979.[82] Billions in cash and weapons, which included over two thousand FIM-92 Stinger surface-to-air missiles, were provided by the United States and Saudi Arabia to Pakistan.[83][84][85]

The Soviet war in Afghanistan resulted in the deaths of over 1 million Afghans, mostly civilians,[86][87][88] and the creation of about 6 million refugees who fled Afghanistan, mainly to Pakistan and Iran.[89] Faced with mounting international pressure and numerous casualties, the Soviets withdrew in 1989 but continued to support Afghan President Mohammad Najibullah until 1992.[90]

Civil war

From 1989 until 1992, Najibullah's government tried to solve the ongoing civil war with economic and military aid, but without Soviet troops on the ground. Najibullah tried to build support for his government by portraying his government as Islamic, and in the 1990 constitution the country officially became an Islamic state and all references of communism were removed. Nevertheless, Najibullah did not win any significant support, and with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, he was left without foreign aid. This, coupled with the internal collapse of his government, led to his ousting from power in April 1992. After the fall of Najibullah's government in 1992, the post-communist Islamic State of Afghanistan was established by the Peshawar Accord, a peace and power-sharing agreement under which all the Afghan parties were united in April 1992, except for the Pakistani supported Hezb-e Islami of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Hekmatyar started a bombardment campaign against the capital city Kabul, which marked the beginning of a new phase in the war.[91]

Saudi Arabia and Iran supported different Afghan militias[92][93][94] and instability quickly developed.[95] The conflict between the two militias soon escalated into a full-scale war.

Due to the sudden initiation of the war, working government departments, police units, and a system of justice and accountability for the newly created Islamic State of Afghanistan did not have time to form. Atrocities were committed by individuals of the different armed factions while Kabul descended into lawlessness and chaos.[93][96] Because of the chaos, some leaders increasingly had only nominal control over their (sub-)commanders.[97] For civilians there was little security from murder, rape, and extortion.[97] An estimated 25,000 people died during the most intense period of bombardment by Hekmatyar's Hezb-i Islami and the Junbish-i Milli forces of Abdul Rashid Dostum, who had created an alliance with Hekmatyar in 1994.[96] Half a million people fled Afghanistan.[97]

Southern and eastern Afghanistan were under the control of local commanders such as Gul Agha Sherzai and others. In 1994, the Taliban (a movement originating from Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-run religious schools for Afghan refugees in Pakistan) also developed in Afghanistan as a political-religious force.[98] The Taliban took control of Kabul and several provinces in southern and central Afghanistan in 1994 and forced the surrender of dozens of local Pashtun leaders.[97]

In late 1994, forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud held on to Kabul and bombardment of the city came to a halt.[96][99][100] The Islamic State government took steps to open courts, restore law and order,[101] and initiate a nationwide political process with the goal of national consolidation and democratic elections. Massoud invited Taliban leaders to join the process but they refused.[102]

Taliban Emirate and Northern Alliance

The Taliban's early victories in 1994 were followed by a series of defeats that resulted in heavy losses that led analysts to believe the Taliban movement had run its course.[97] The Taliban started shelling Kabul in early 1995 but were repelled by forces under Massoud.[99][99][103]

On 26 September 1996, as the Taliban, with military support from Pakistan[92][92][104] and financial support from Saudi Arabia, prepared for another major offensive, Massoud ordered a full retreat from Kabul.[105] The Taliban seized Kabul on 27 September 1996, and established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. They imposed on the parts of Afghanistan under their control their political and judicial interpretation of Islam, issuing edicts especially targeting women.[106] According to Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), "no other regime in the world has methodically and violently forced half of its population into virtual house arrest, prohibiting them on pain of physical punishment."[106]

After the fall of Kabul to the Taliban, Massoud and Dostum created the United Front (Northern Alliance).[107] The United Front included Massoud's predominantly Tajik forces, Dostum's Uzbek forces, and Hazara and Pashtun factions under leaders such as Haji Mohammad Mohaqiq, Abdul Haq, and Abdul Qadir. The Taliban defeated Dostum's forces during the Battles of Mazar-i-Sharif (1997–98). The Taliban committed systematic massacres against civilians in northern and western Afghanistan[108][109][110][111]

Pakistan's Chief of Army Staff, Pervez Musharraf, was responsible for sending tens of thousands of Pakistanis to fight alongside the Taliban and bin Laden against Northern Alliance forces.[102][104][112][113][114] In 2001 alone, there were believed to be 28,000 Pakistani nationals fighting inside Afghanistan.[102][115] From 1996 to 2001, the al-Qaeda network of Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri was harbored by the Taliban in Afghanistan,[116] and bin Laden sent thousands of Arab recruits to fight against the United Front.[115][116][117]

Massoud remained the only leader of the United Front in Afghanistan. In the areas under his control, Massoud set up democratic institutions and signed the Women's Rights Declaration.[118] The fighting also caused around 1 million people to flee Taliban controlled areas.[112][119][120] From 1990 to September 2001, 400,000 Afghan civilians have reportedly died in the wars.[121]

On 9 September 2001, Massoud was assassinated by two French-speaking Arab suicide attackers inside Afghanistan, and two days later the September 11 attacks were carried out in the United States. The US government identified Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda as the perpetrators of the attacks, and demanded that the Taliban hand over bin Laden.[122] After refusing to comply with the US demand, the October 2001 Operation Enduring Freedom was launched. During the initial invasion, US and UK forces bombed parts of Afghanistan and worked with ground forces of the Northern Alliance to remove the Taliban from power and destroy al-Qaeda training camps.[123]

Recent history (2002–present)

In December 2001, after the Taliban government was toppled and the new Afghan government under Hamid Karzai was formed, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) was established by the UN Security Council to help assist the Karzai administration and provide basic security.[124][125] Taliban forces also began regrouping inside Pakistan, while more coalition troops entered Afghanistan and began rebuilding the war-torn country.[126][127]

Shortly after their fall from power, the Taliban began an insurgency to regain control of Afghanistan. Over the next decade, ISAF and Afghan troops led many offensives against the Taliban but failed to fully defeat them. Afghanistan remained one of the poorest countries in the world due to a lack of foreign investment, government corruption, and the Taliban insurgency.[128][129]

Meanwhile, the Afghan government was able to build some democratic structures, and, on December 7, 2004, the country changed its name to the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Attempts were made, often with the support of foreign donor countries, to improve the country's economy, healthcare, education, transport, and agriculture. ISAF forces also began to train the Afghan armed forces and police. In the decade following 2002, over five million Afghan refugees were repatriated to the country, including many who were forcefully deported from Western countries.[130][131]

By 2009, a Taliban-led shadow government began to form in many parts of the country.[132] US President Barack Obama announced that the U.S. would deploy another 30,000 U.S. soldiers to the country in 2010 for a period of two years. In 2010, Karzai attempted to hold peace negotiations with the Taliban and other groups, but these groups refused to attend and bombings, assassinations, and ambushes intensified.[133]

After the May 2011 death of Osama bin Laden in Pakistan, many prominent Afghan figures were assassinated,[134] Afghanistan–Pakistan border skirmishes intensified, and many large scale attacks by the Pakistani-based Haqqani Network took place across Afghanistan. The United States warned the Pakistani government of possible military action within Pakistan if the government refused to attack these forces in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas,[135] as the United States blamed rogue elements within the Pakistani government for the increased attacks.[136] The Pakistani Army began to intensify their attacks against these groups as part of the War in North-West Pakistan.

Following the 2014 presidential election President Hamid Karzai left power and Ashraf Ghani became President on 29 September 2014.[137] The US war in Afghanistan (America's longest war) officially ended on December 28, 2014. However, thousands of US-led NATO troops have remained in the country to train and advise Afghan government forces.[138]

Geography

A landlocked mountainous country with plains in the north and southwest, Afghanistan is variously described as being located within Central Asia[15][139] or South Asia.[14][140][141] It is part of the US coined Greater Middle East Muslim world, which lies between latitudes 29° N and 39° N, and longitudes 60° E and 75° E. The country's highest point is Noshaq, at 7,492 m (24,580 ft) above sea level. It has a continental climate with harsh winters in the central highlands, the glaciated northeast (around Nuristan), and the Wakhan Corridor, where the average temperature in January is below −15 °C (5 °F), and hot summers in the low-lying areas of the Sistan Basin of the southwest, the Jalalabad basin in the east, and the Turkestan plains along the Amu River in the north, where temperatures average over 35 °C (95 °F) in July.

Despite having numerous rivers and reservoirs, large parts of the country are dry. The endorheic Sistan Basin is one of the driest regions in the world.[142] Aside from the usual rainfall, Afghanistan receives snow during the winter in the Hindu Kush and Pamir Mountains, and the melting snow in the spring season enters the rivers, lakes, and streams.[143][144] However, two-thirds of the country's water flows into the neighboring countries of Iran, Pakistan, and Turkmenistan. The state needs more than US$2 billion to rehabilitate its irrigation systems so that the water is properly managed.[145]

The northeastern Hindu Kush mountain range, in and around the Badakhshan Province of Afghanistan, is in a geologically active area where earthquakes may occur almost every year.[146] They can be deadly and destructive sometimes, causing landslides in some parts or avalanches during the winter.[147] The last strong earthquakes were in 1998, which killed about 6,000 people in Badakhshan near Tajikistan.[148] This was followed by the 2002 Hindu Kush earthquakes in which over 150 people were killed and over 1,000 injured. A 2010 earthquake left 11 Afghans dead, over 70 injured, and more than 2,000 houses destroyed.

The country's natural resources include: coal, copper, iron ore, lithium, uranium, rare earth elements, chromite, gold, zinc, talc, barites, sulfur, lead, marble, precious and semi-precious stones, natural gas, and petroleum, among other things.[149][150] In 2010, US and Afghan government officials estimated that untapped mineral deposits located in 2007 by the US Geological Survey are worth between $900 bn and $3 trillion.[151][152][153]

At 652,230 km2 (251,830 sq mi),[154] Afghanistan is the world's 41st largest country,[155] slightly bigger than France and smaller than Burma, about the size of Texas in the United States. It borders Pakistan in the south and east; Iran in the west; Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan in the north; and China in the far east.

Demographics

As of 2012, the population of Afghanistan is around 31,108,077,[156] which includes the roughly 2.7 million Afghan refugees still living in Pakistan and Iran. In 1979, the population was reported to be about 15.5 million.[157] The only city with over a million residents is its capital, Kabul. Other large cities in the country are, in order of population size, Kandahar, Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif, Jalalabad, Lashkar Gah, Taloqan, Khost, Sheberghan, and Ghazni. Urban areas are experiencing rapid population growth following the return of over 5 million expats. According to the Population Reference Bureau, the Afghan population is estimated to increase to 82 million by 2050.[158]

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||||||

Kabul  Kandahar |

1 | Kabul | Kabul Province | 3,071,400 |  Herat  Mazar-i-Sharif | ||||

| 2 | Kandahar | Kandahar Province | 512,000 | ||||||

| 3 | Herat | Herat Province | 397,456 | ||||||

| 4 | Mazar-i-Sharif | Balkh Province | 375,000 | ||||||

| 5 | Jalalabad | Nangarhar Province | 205,423 | ||||||

| 6 | Lashkar Gar | Helmand Province | 201,546 | ||||||

| 7 | Taloqan | Takhar Province | 196,400 | ||||||

| 8 | Khost | Khost Province | 160,214 | ||||||

| 9 | Sheberghan | Jowzjan Province | 148,329 | ||||||

| 10 | Ghazni | Ghazni Province | 141,000 | ||||||

Ethnic groups

Afghanistan is a multiethnic society, and its historical status as a crossroads has contributed significantly to its diverse ethnic makeup.[160] The population of the country is divided into a wide variety of ethnolinguistic groups. Because a systematic census has not been held in the nation in decades, exact figures about the size and composition of the various ethnic groups are unavailable.[161] An approximate distribution of the ethnic groups is shown in the chart below:

| Ethnic group | World Factbook / Library of Congress Country Studies estimate (2004–present)[43][162] | World Factbook / Library of Congress Country Studies estimate (pre-2004)[163][164][165][166] |

|---|---|---|

| Pashtun | 42% | 38–55% |

| Tajik | 27% | 26% (of this 1% are Qizilbash) |

| Hazara | 8% | 9–10% |

| Uzbek | 9% | 6–8% |

| Aimaq | 4% | 500,000 to 800,000 |

| Turkmen | 3% | 2.5% |

| Baloch | 2% | 100,000 |

| Others (Pashayi, Nuristani, Arab, Brahui, Pamiri, Gurjar, etc.) | 4% | 6.9% |

Languages

Pashto and Dari are the official languages of Afghanistan; bilingualism is very common.[1] Both are Indo-European languages from the Iranian languages sub-family. Dari (Afghan Persian) has long been the prestige language and a lingua franca for inter-ethnic communication. It is the native tongue of the Tajiks, Hazaras, Aimaks, and Kizilbash.[168] Pashto is the native tongue of the Pashtuns, although many Pashtuns often use Dari and some non-Pashtuns are fluent in Pashto.

Other languages, including Uzbek, Arabic, Turkmen, Balochi, Pashayi, and Nuristani languages (Ashkunu, Kamkata-viri, Vasi-vari, Tregami, and Kalasha-ala), are the native tongues of minority groups across the country and have official status in the regions where they are widely spoken. Minor languages also include Pamiri (Shughni, Munji, Ishkashimi, and Wakhi), Brahui, Hindko, and Kyrgyz. A small percentage of Afghans are also fluent in Urdu, English, and other languages.

Religions

Over 99% of the Afghan population is Muslim; approximately 80–85% are from the Sunni branch, 15–19% are Shia.[43][169][170][171] Until the 1890s, the region around Nuristan was known as Kafiristan (land of the kafirs (unbelievers)) because of its non-Muslim inhabitants, the Nuristanis, an ethnically distinct people whose religious practices included animism, polytheism, and shamanism.[172] Thousands of Afghan Sikhs and Hindus are also found in the major cities.[173][174] There was a small Jewish community in Afghanistan who had emigrated to Israel and the United States by the end of the twentieth century; only one Jew, Zablon Simintov, remained by 2005.[175]

Governance

Afghanistan is an Islamic republic consisting of three branches, the executive, legislative, and judicial. The nation was led by Hamid Karzai as the President and leader since late 2001 till 2014. Currently the new president is Ashraf Ghani with Abdul Rashid Dostum and Sarwar Danish as vise presidents. Abdullah Abdullah serves as the chief executive officer (CEO). The National Assembly is the legislature, a bicameral body having two chambers, the House of the People and the House of Elders.

The Supreme Court is led by Chief Justice Abdul Salam Azimi, a former university professor who had been a legal advisor to the president.[176] The current court is seen as more moderate and led by more technocrats than the previous one, which was dominated by fundamentalist religious figures such as Chief Justice Faisal Ahmad Shinwari, who issued several controversial rulings, including seeking to place a limit on the rights of women.

According to Transparency International's 2010 corruption perceptions index results, Afghanistan was ranked as the third most corrupt country in the world.[177] A January 2010 report published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime revealed that bribery consumed an amount equal to 23% of the GDP of the nation.[178] A number of government ministries are believed to be rife with corruption, and while President Karzai vowed to tackle the problem in late 2009 by stating that "individuals who are involved in corruption will have no place in the government",[179] top government officials were stealing and misusing hundreds of millions of dollars through the Kabul Bank. Although the nation's institutions are newly formed and steps have been taken to arrest some,[180] the United States warned that aid to Afghanistan would be greatly reduced if the corruption is not stopped.[181]

Elections and parties

The 2004 Afghan presidential election was relatively peaceful, in which Hamid Karzai won in the first round with 55.4% of the votes. However, the 2009 presidential election was characterized by lack of security, low voter turnout, and widespread electoral fraud.[182][183] The vote, along with elections for 420 provincial council seats, took place in August 2009, but remained unresolved during a lengthy period of vote counting and fraud investigation.[184]

Two months later, under international pressure, a second round run-off vote between Karzai and remaining challenger Abdullah was announced, but a few days later Abdullah announced that he would not participate in the 7 November run-off because his demands for changes in the electoral commission had not been met. The next day, officials of the election commission cancelled the run-off and declared Hamid Karzai as President for another five-year term.[183]

In the 2005 parliamentary election, among the elected officials were former mujahideen, Islamic fundamentalists, warlords, communists, reformists, and several Taliban associates.[185] In the same period, Afghanistan reached to the 30th highest nation in terms of female representation in parliament.[186] The last parliamentary election was held in September 2010, but due to disputes and investigation of fraud, the swearing-in ceremony took place in late January 2011. The 2014 presidential election ended with Ashraf Ghani winning by 56.44% votes.[187]

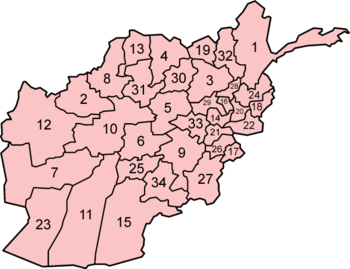

Administrative divisions

Afghanistan is administratively divided into 34 provinces (wilayats), with each province having its own capital and a provincial administration. The provinces are further divided into about 398 smaller provincial districts, each of which normally covers a city or a number of villages. Each district is represented by a district governor.

The provincial governors are appointed by the President of Afghanistan and the district governors are selected by the provincial governors. The provincial governors are representatives of the central government in Kabul and are responsible for all administrative and formal issues within their provinces. There are also provincial councils that are elected through direct and general elections for a period of four years.[188] The functions of provincial councils are to take part in provincial development planning and to participate in the monitoring and appraisal of other provincial governance institutions.

According to article 140 of the constitution and the presidential decree on electoral law, mayors of cities should be elected through free and direct elections for a four-year term. However, due to huge election costs, mayoral and municipal elections have never been held. Instead, mayors have been appointed by the government. In the capital city of Kabul, the mayor is appointed by the President of Afghanistan.

The following is a list of all the 34 provinces in alphabetical order:

Foreign relations and military

The Afghan Ministry of Foreign Affairs is in charge of maintaining the foreign relations of Afghanistan. The state has been a member of the United Nations since 1946. It enjoys strong economic relations with a number of NATO and allied states, particularly the United States, United Kingdom, Germany and Turkey. In 2012, the United States designated Afghanistan as a major non-NATO ally and created the U.S.–Afghanistan Strategic Partnership Agreement. Afghanistan also has friendly diplomatic relations with neighboring Pakistan, Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and China, and with regional states such as India, Bangladesh, Kazakhstan, Russia, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Egypt, Japan, and South Korea. It continues to develop diplomatic relations with other countries around the world.

The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) was established in 2002 under United Nations Security Council Resolution 1401 in order to help the country recover from decades of war. Today, a number of NATO member states deploy about 38,000 troops in Afghanistan as part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF).[189] Its main purpose is to train the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF). The Afghan Armed Forces are under the Ministry of Defense, which includes the Afghan National Army (ANA) and the Afghan Air Force (AAF). The ANA is divided into 7 major Corps, with the 201st Selab ("Flood") in Kabul followed by the 203rd in Gardez, 205th Atul ("Hero") in Kandahar, 207th in Herat, 209th in Mazar-i-Sharif, and the 215th in Lashkar Gah. The ANA also has a commando brigade, which was established in 2007. The Afghan Defense University (ADU) houses various educational establishments for the Afghan Armed Forces, including the National Military Academy of Afghanistan.

Law enforcement

The National Directorate of Security (NDS) is the nation's domestic intelligence agency, which operates similar to that of the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and has between 15,000 to 30,000 employees. The nation also has about 126,000 national police officers, with plans to recruit more so that the total number can reach 160,000.[190] The Afghan National Police (ANP) is under the Ministry of the Interior and serves as a single law enforcement agency all across the country. The Afghan National Civil Order Police is the main branch of the ANP, which is divided into five Brigades, each commanded by a Brigadier General. These brigades are stationed in Kabul, Gardez, Kandahar, Herat, and Mazar-i-Sharif. Every province has an appointed provincial Chief of Police who is responsible for law enforcement throughout the province.

The police receive most of their training from Western forces under the NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan. According to a 2009 news report, a large proportion of police officers were illiterate and accused of demanding bribes.[191] Jack Kem, deputy to the commander of NATO Training Mission Afghanistan and Combined Security Transition Command Afghanistan, stated that the literacy rate in the ANP would rise to over 50% by January 2012. What began as a voluntary literacy program became mandatory for basic police training in early 2011.[190] Approximately 17% of them tested positive for illegal drug use. In 2009, President Karzai created two anti-corruption units within the Interior Ministry.[192] Former Interior Minister Hanif Atmar said that security officials from the US (FBI), Britain (Scotland Yard), and the European Union will train prosecutors in the unit.

The southern and eastern parts of Afghanistan are the most dangerous due to militant activities and the flourishing drug trade. These particular areas are sometimes patrolled by Taliban insurgents, who often plant improvised explosive devices (IEDs) on roads and carry out suicide bombings. Kidnapping and robberies are also reported. Every year many Afghan police officers are killed in the line of duty in these areas. The Afghan Border Police (ABP) are responsible for protecting the nation's airports and borders, especially the disputed Durand Line border, which is often used by members of criminal organizations and terrorists for their illegal activities. A report in 2011 suggested that up to 3 million people were involved in the illegal drug business in Afghanistan. Many of the attacks on government employees may be ordered by powerful mafia groups. Drugs from Afghanistan are exported to neighboring countries and worldwide. The Afghan Ministry of Counter Narcotics is tasked to deal with these issues by bringing to justice major drug traffickers.[193]

Economy

Afghanistan is an impoverished and least developed country, one of the world's poorest because of decades of war and lack of foreign investment. As of 2013, the nation's GDP stands at about $45.3 billion with an exchange rate of $20.65 billion, and the GDP per capita is $1,100. The country's exports totaled $2.6 billion in 2010. Its unemployment rate is about 35% and roughly the same percentage of its citizens live below the poverty line.[194] According to a 2009 report, about 42% of the population lives on less than $1 a day.[195] The nation has less than $1.5 billion in external debt and is recovering with the assistance of the world community.[194]

The Afghan economy has been growing at about 10% per year in the last decade, which is due to the infusion of over $50 billion in international aid and remittances from Afghan expats.[194] It is also due to improvements made to the transportation system and agricultural production, which is the backbone of the nation's economy.[196] The country is known for producing some of the finest pomegranates, grapes, apricots, melons, and several other fresh and dry fruits, including nuts.[197] Many sources indicate that as much as 11% or more of Afghanistan's economy is derived from the cultivation and sale of opium, and Afghanistan is widely considered the world's largest producer of opium despite Afghan government and international efforts to eradicate the crop.[198][199]

While the nation's current account deficit is largely financed with donor money, only a small portion is provided directly to the government budget. The rest is provided to non-budgetary expenditure and donor-designated projects through the United Nations system and non-governmental organizations. The Afghan Ministry of Finance is focusing on improved revenue collection and public sector expenditure discipline. For example, government revenues increased 31% to $1.7 billion from March 2010 to March 2011.

Da Afghanistan Bank serves as the central bank of the nation and the "Afghani" (AFN) is the national currency, with an exchange rate of about 47 Afghanis to 1 US dollar. Since 2003, over 16 new banks have opened in the country, including Afghanistan International Bank, Kabul Bank, Azizi Bank, Pashtany Bank, Standard Chartered Bank, and First Micro Finance Bank.

One of the main drivers for the current economic recovery is the return of over 5 million expatriates, who brought with them fresh energy, entrepreneurship and wealth-creating skills as well as much needed funds to start up businesses. For the first time since the 1970s, Afghans have involved themselves in construction, one of the largest industries in the country.[200] Some of the major national construction projects include the $35 billion New Kabul City next to the capital, the Ghazi Amanullah Khan City near Jalalabad, and the Aino Mena in Kandahar.[201][202][203] Similar development projects have also begun in Herat, Mazar-e-Sharif, and other cities.[204]

In addition, a number of companies and small factories began operating in different parts of the country, which not only provide revenues to the government but also create new jobs. Improvements to the business environment have resulted in more than $1.5 billion in telecom investment and created more than 100,000 jobs since 2003.[205] Afghan rugs are becoming popular again, allowing many carpet dealers around the country to hire more workers.

Afghanistan is a member of SAARC, ECO, and OIC. It holds an observer status in SCO. Foreign Minister Zalmai Rassoul told the media in 2011 that his nation's "goal is to achieve an Afghan economy whose growth is based on trade, private enterprise and investment".[206] Experts believe that this will revolutionize the economy of the region. Opium production in Afghanistan soared to a record in 2007 with about 3 million people reported to be involved in the business,[207] but then declined significantly in the years following.[208] The government started programs to help reduce poppy cultivation, and by 2010 it was reported that 24 out of the 34 provinces were free from poppy growing.

In June 2012, India advocated for private investments in the resource rich country and the creation of a suitable environment therefor.[209]

Mining

Michael E. O'Hanlon of the Brookings Institution estimated that if Afghanistan generates about $10 bn per year from its mineral deposits, its gross national product would double and provide long-term funding for Afghan security forces and other critical needs.[210] The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimated in 2006 that northern Afghanistan has an average 2.9 billion (bn) barrels (bbl) of crude oil, 15.7 trillion cubic feet (440 bn m3) of natural gas, and 562 million bbl of natural gas liquids.[211] In December 2011, Afghanistan signed an oil exploration contract with China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) for the development of three oil fields along the Amu Darya river in the north.[212]

Other reports show that the country has huge amounts of lithium, copper, gold, coal, iron ore, and other minerals.[149][150][213] The Khanashin carbonatite in Helmand Province contains 1,000,000 metric tons (1,100,000 short tons) of rare earth elements.[214] In 2007, a 30-year lease was granted for the Aynak copper mine to the China Metallurgical Group for $3 billion,[215] making it the biggest foreign investment and private business venture in Afghanistan's history.[216] The state-run Steel Authority of India won the mining rights to develop the huge Hajigak iron ore deposit in central Afghanistan.[217] Government officials estimate that 30% of the country's untapped mineral deposits are worth between $900 bn and $3 trillion.[151][152][153] One official asserted that "this will become the backbone of the Afghan economy" and a Pentagon memo stated that Afghanistan could become the "Saudi Arabia of lithium".[152][218][219][220] In a 2011 news story, the CSM reported, "The United States and other Western nations that have borne the brunt of the cost of the Afghan war have been conspicuously absent from the bidding process on Afghanistan's mineral deposits, leaving it mostly to regional powers."[221]

Transportation

Air

Air transport in Afghanistan is provided by the national carrier, Ariana Afghan Airlines (AAA), and by private companies such as Afghan Jet International, East Horizon Airlines, Kam Air, Pamir Airways, and Safi Airways. Airlines from a number of countries also provide flights in and out of the country. These include Air India, Emirates, Gulf Air, Iran Aseman Airlines, Pakistan International Airlines, and Turkish Airlines.

The country has four international airports: Herat International Airport, Hamid Karzai International Airport (formerly Kabul International Airport), Kandahar International Airport, and Mazar-e Sharif International Airport. There are also around a dozen domestic airports with flights to Kabul or Herat.

Rail

As of 2014, the country has only two rail links, one a 75 km line from Kheyrabad to the Uzbekistan border and the other a 10 km long line from Toraghundi to the Turkmenistan border. Both lines are used for freight only and there is no passenger service as of yet. There are various proposals for the construction of additional rail lines in the country.[222] In 2013, the presidents of Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan attended the groundbreaking ceremony for a 225 km line between Turkmenistan-Andkhvoy-Mazar-i-Sharif-Kheyrabad. The line will link at Kheyrabad with the existing line to the Uzbekistan border.[223] Plans exist for a rail line from Kabul to the eastern border town of Torkham, where it will connect with Pakistan Railways.[224] There are also plans to finish a rail line between Khaf, Iran and Herat, Afghanistan.[225]

Roads

Traveling by bus in Afghanistan remains dangerous due to careless and intoxicated bus drivers as well as militant activities. The buses are usually older model Mercedes-Benz and owned by private companies. Serious traffic accidents are common on Afghan roads and highways, particularly on the Kabul–Kandahar and the Kabul–Jalalabad Road.[226]

Newer automobiles have recently become more widely available after the rebuilding of roads and highways. They are imported from the United Arab Emirates through Pakistan and Iran. As of 2012, vehicles more than 10 years old are banned from being imported into the country. The development of the nation's road network is a major boost for the economy due to trade with neighboring countries. Postal services in Afghanistan are provided by the publicly owned Afghan Post and private companies such as FedEx, DHL, and others.

Communication

Telecommunication services in the country are provided by Afghan Wireless, Etisalat, Roshan, MTN Group, and Afghan Telecom. In 2006, the Afghan Ministry of Communications signed a $64.5 million agreement with ZTE for the establishment of a countrywide optical fiber cable network. As of 2011, Afghanistan had around 17 million GSM phone subscribers and over 1 million internet users, but only had about 75,000 fixed telephone lines and a little over 190,000 CDMA subscribers.[227] 3G services are provided by Etisalat and MTN Group. In 2014, Afghanistan leased a space satellite from Eutelsat, called AFGHANSAT 1.[228]

Health

According to the Human Development Index, Afghanistan is the 15th least developed country in the world. The average life expectancy is estimated to be around 60 years for both sexes.[229] The country has the ninth highest total fertility rate in the world, at 5.64 children born/woman (according to 2012 estimates).[230] It has one of the highest maternal mortality rate in the world, estimated in 2010 at 460 deaths/100,000 live births,[231] and the highest infant mortality rate in the world (deaths of babies under one year), estimated in 2012 to be 119.41 deaths/1,000 live births.[232] Data from 2010 suggest that one in ten children die before they are five years old.[233] The Ministry of Public Health plans to cut the infant mortality rate to 400 for every 100,000 live births before 2020.[234] The country currently has more than 3,000 midwives, with an additional 300 to 400 being trained each year.[235]

A number of hospitals and clinics have been built over the last decade, with the most advanced treatments being available in Kabul. The French Medical Institute for Children and Indira Gandhi Childrens Hospital in Kabul are the leading children's hospitals in the country. Some of the other main hospitals in Kabul include the 350-bed Jamhuriat Hospital and the Jinnah Hospital, which is still under construction. There are also a number of well-equipped military-controlled hospitals in different regions of the country.

It was reported in 2006 that nearly 60% of the population lives within a two-hour walk of the nearest health facility, up from 9% in 2002.[236] The latest surveys show that 57% of Afghans say they have good or very good access to clinics or hospitals.[235] The nation has one of the highest incidences of people with disabilities, with around a million people affected.[237] About 80,000 people are missing limbs; most of these were injured by landmines.[238][239] Non-governmental charities such as Save the Children and Mahboba's Promise assist orphans in association with governmental structures.[240] Demographic and Health Surveys is working with the Indian Institute of Health Management Research and others to conduct a survey in Afghanistan focusing on maternal death, among other things.[241]

Education

Education in the country includes K–12 and higher education, which is supervised by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Higher Education.[242] The nation's education system was destroyed due to the decades of war, but it began reviving after the Karzai administration came to power in late 2001. More than 5,000 schools were built or renovated in the last decade, with more than 100,000 teachers being trained and recruited.[243] More than seven million male and female students are enrolled in schools,[243] with about 100,000 being enrolled in different universities around the country; at least 35% of these students are female. As of 2013, there are 16,000 schools across Afghanistan. Education Minister Ghulam Farooq Wardak stated that another 8,000 schools are required to be constructed for the remaining 3 million children who are deprived of education.[244]

Kabul University reopened in 2002 to both male and female students. In 2006, the American University of Afghanistan was established in Kabul, with the aim of providing a world-class, English-language, co-educational learning environment in Afghanistan. The capital of Kabul serves as the learning center of Afghanistan, with many of the best educational institutions being based there. Major universities outside of Kabul include Kandahar University in the south, Herat University in the northwest, Balkh University in the north, Nangarhar University and Khost University in the east. The National Military Academy of Afghanistan, modeled after the United States Military Academy at West Point, is a four-year military development institution dedicated to graduating officers for the Afghan Armed Forces. The $200 million Afghan Defense University is under construction near Qargha in Kabul. The United States is building six faculties of education and five provincial teacher training colleges around the country, two large secondary schools in Kabul, and one school in Jalalabad.[243]

The literacy rate of the entire population has been very low but is now rising because more students go to schools.[245] In 2010, the United States began establishing a number of Lincoln learning centers in Afghanistan. They are set up to serve as programming platforms offering English language classes, library facilities, programming venues, Internet connectivity, and educational and other counseling services. A goal of the program is to reach at least 4,000 Afghan citizens per month per location.[246][247] The Afghan National Security Forces are provided with mandatory literacy courses.[245] In addition to this, Baghch-e-Simsim (based on the American Sesame Street) was launched in late 2011 to help young Afghan children learn.

In 2009 and 2010, a 5,000 OLPC - One Laptop Per Child schools deployment took place in Kandahar with funding from an anonymous foundation.[248] The OLPC team seeks local support to undertake larger deployment.[249][250]

Culture

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

|

Mythology and folklore

|

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

|

Art

|

|

Literature Afghan poetry |

|

Music and performing arts

|

|

Media |

| Sport |

|

Monuments

|

|

Symbols

|

|

The Afghan culture has been around for over two millennia, tracing back to at least the time of the Achaemenid Empire in 500 BCE.[251][252] It is mostly a nomadic and tribal society, with different regions of the country having their own traditions, reflecting the multi-cultural and multi-lingual character of the nation. In the southern and eastern region the people live according to the Pashtun culture by following Pashtunwali, which is an ancient way of life that is still preserved.[253] The remainder of the country is culturally Persian. Some non-Pashtuns who live in proximity with Pashtuns have adopted Pashtunwali[254] in a process called Pashtunization (or Afghanization), while some Pashtuns have been Persianized. Millions of Afghans who have been living in Pakistan and Iran over the last 30 years have been influenced by the cultures of those neighboring nations.

Afghans display pride in their culture, nation, ancestry, and above all, their religion and independence. Like other highlanders, they are regarded with mingled apprehension and condescension, for their high regard for personal honor, for their tribe loyalty and for their readiness to use force to settle disputes.[255] As tribal warfare and internecine feuding has been one of their chief occupations since time immemorial, this individualistic trait has made it difficult for foreigners to conquer them. Tony Heathcote considers the tribal system to be the best way of organizing large groups of people in a country that is geographically difficult, and in a society that, from a materialistic point of view, has an uncomplicated lifestyle.[255] There are an estimated 60 major Pashtun tribes,[256] and the Afghan nomads are estimated at about 2–3 million.[257]

The nation has a complex history that has survived either in its current cultures or in the form of various languages and monuments. However, many of its historic monuments have been damaged in recent wars.[258] The two famous Buddhas of Bamiyan were destroyed by the Taliban, who regarded them as idolatrous. Despite that, archaeologists are still finding Buddhist relics in different parts of the country, some of them dating back to the 2nd century.[259][260][261] This indicates that Buddhism was widespread in Afghanistan. Other historical places include the cities of Herat, Kandahar, Ghazni, Mazar-i-Sharif, and Zarang. The Minaret of Jam in the Hari River valley is a UNESCO World Heritage site. A cloak reputedly worn by Islam's prophet Muhammad is kept inside the Shrine of the Cloak in Kandahar, a city founded by Alexander and the first capital of Afghanistan. The citadel of Alexander in the western city of Herat has been renovated in recent years and is a popular attraction for tourists. In the north of the country is the Shrine of Hazrat Ali, believed by many to be the location where Ali was buried. The Afghan Ministry of Information and Culture is renovating 42 historic sites in Ghazni until 2013, when the province will be declared as the capital of Islamic civilization.[262] The National Museum of Afghanistan is located in Kabul.

Although literacy is low, classic Persian and Pashto poetry plays an important role in the Afghan culture. Poetry has always been one of the major educational pillars in the region, to the level that it has integrated itself into culture. Some notable poets include Rumi, Rabi'a Balkhi, Sanai, Jami, Khushal Khan Khattak, Rahman Baba, Khalilullah Khalili, and Parween Pazhwak.[263]

Media and entertainment

The Afghan mass media began in the early 20th century, with the first newspaper published in 1906. By the 1920s, Radio Kabul was broadcasting local radio services. Afghanistan National Television was launched in 1974 but was closed in 1996 when the media was tightly controlled by the Taliban.[264] Since 2002, press restrictions have been gradually relaxed and private media diversified. Freedom of expression and the press is promoted in the 2004 constitution and censorship is banned, although defaming individuals or producing material contrary to the principles of Islam is prohibited. In 2008, Reporters Without Borders ranked the media environment as 156 out of 173 countries, with the 1st being the most free. Around 400 publications were registered, at least 15 local Afghan television channels, and 60 radio stations.[265] Foreign radio stations, such as Voice of America, BBC World Service, and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) broadcast into the country.

The city of Kabul has been home to many musicians who were masters of both traditional and modern Afghan music. Traditional music is especially popular during the Nowruz (New Year) and National Independence Day celebrations. Ahmad Zahir, Nashenas, Ustad Sarahang, Sarban, Ubaidullah Jan, Farhad Darya, and Naghma are some of the notable Afghan musicians, but there are many others.[266] Most Afghans are accustomed to watching Bollywood films from India and listening to its filmi hit songs. Many major Bollywood film stars have roots in Afghanistan, including Salman Khan, Saif Ali Khan, Shah Rukh Khan (SRK), Aamir Khan, Feroz Khan, Kader Khan, Naseeruddin Shah, and Celina Jaitley. In addition, several Bollywood films, such as Dharmatma, Khuda Gawah, Escape from Taliban, and Kabul Express have been shot inside Afghanistan.

Sports

The Afghanistan national football team has been competing in international football since 1941. The national team plays its home games at the Ghazi Stadium in Kabul, while football in Afghanistan is governed by the Afghanistan Football Federation. The national team has never competed or qualified for the FIFA World Cup, but has recently won an international football trophy in the SAFF Championship. The country also has a national team in the sport of futsal, a 5-a-side variation of football.

The other most popular sport in Afghanistan is cricket. The Afghan national cricket team, which was formed in the last decade, participated in the 2009 ICC World Cup Qualifier, 2010 ICC World Cricket League Division One and the 2010 ICC World Twenty20. It won the ACC Twenty20 Cup in 2007, 2009, 2011 and 2013. The team eventually made it to play in the 2015 Cricket World Cup. The Afghanistan Cricket Board (ACB) is the official governing body of the sport and is headquartered in Kabul. The Ghazi Amanullah Khan International Cricket Stadium serves as the nation's main cricket stadium, followed by the Kabul National Cricket Stadium. Several other stadiums are under construction.[267] Domestically, cricket is played between teams from different provinces.

Other popular sports in Afghanistan include basketball, volleyball, taekwondo, and bodybuilding.[268] Buzkashi is a traditional sport, mainly among the northern Afghans. It is similar to polo, played by horsemen in two teams, each trying to grab and hold a goat carcass. The Afghan Hound (a type of running dog) originated in Afghanistan and was originally used in hunting.

See also

- Outline of Afghanistan

- Index of Afghanistan-related articles

- Bibliography of Afghanistan

- Afghanistanism

- International rankings of Afghanistan

- Environment of Afghanistan

- Water supply and sanitation in Afghanistan

- List of power stations in Afghanistan

- List of dams and reservoirs in Afghanistan

Notes

| a.^ | Other terms that have been used as demonyms are Afghani[269] and Afghanistani.[270] |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Article Sixteen of the 2004 Constitution of Afghanistan". 2004. Archived from the original on 2013-10-28. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

From among the languages of Pashto, Dari, Uzbeki, Turkmani, Baluchi, Pashai, Nuristani, Pamiri (alsana), Arab and other languages spoken in the country, Pashto and Dari are the official languages of the state.

- ↑ Central Statistics Organization of Afghanistan: Statistical Yearbook 2012-2013: Area and administrative Population

- ↑ "The World Factbook: Afghanistan". Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Chapter 2. The Society and Its Environment" (PDF). Afghanistan Country Study. Illinois Institute of Technology. pp. 105–06. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2001. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Afghanistan". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ "Gini Index". World Bank. Archived from the original on 2014-05-11. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ↑ "2014 Human Development Report Summary" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2014. pp. 21–25. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook: Afghanistan". Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ "South Asia: Data, Projects, and Research". Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ "MAPS SHOWING GEOLOGY, OIL AND GAS FIELDS AND GEOLOGICAL PROVINCES OF SOUTH ASIA (Includes Afghanistan)". Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ "University of Washington Jackson School of International Studies: The South Asia Center". Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ "Syracruse University: The South Asia Center". Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ "Center for South Asian studies". Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings". UNdata. 26 April 2011. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Afghanistan". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 25 February 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Griffin, Luke (14 January 2002). "The Pre-Islamic Period". Afghanistan Country Study. Illinois Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 3 November 2001. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ↑ "Afghanistan country profile". BBC News. 12 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ↑ Baxter, Craig (1997). "Chapter 1. Historical Setting". Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ "Kingdoms of South Asia – Afghanistan in Far East Kingdoms: Persia and the East". The History Files. Archived from the original on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ "Last Afghan empire". Louis Dupree, Nancy Hatch Dupree and others. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ↑ D. Balland (2010). "Afghanistan x. Political History". Encyclopædia Iranica (online ed.). Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2013-12-12. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ↑ M. Longworth Dames, G. Morgenstierne, and R. Ghirshman (1999). "AFGHĀNISTĀN". Encyclopaedia of Islam (CD-ROM v. 1.0 ed.). Koninklijke Brill NV.

- ↑ Vogelsang, Willem (2002). The Afghans. Wiley Blackwell. p. 18. ISBN 0-631-19841-5. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ Noelle-Karimi, Christine; Conrad J. Schetter; Reinhard Schlagintweit (2002). Afghanistan -a country without a state?. University of Michigan, United States: IKO. p. 18. ISBN 3-88939-628-3. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

The earliest mention of the name 'Afghan' (Abgan) is to be found in a Sasanid inscription from the 3rd century, and it appears in India in the form of 'Avagana'...

- ↑ "Afghan". Ch. M. Kieffer. Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition. December 15, 1983.

- ↑ "Afghan". Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition. December 15, 1983.

- ↑ Banting, Erinn (2003). Afghanistan: The land. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 4. ISBN 0-7787-9335-4. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "General Information About Afghanistan". Abdullah Qazi. Afghanistan Online. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ↑ "Constitution of Afghanistan". 2004. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 "Afghanistan – John Ford Shroder, University of Nebraska". Webcitation.org. Archived from the original on 2013-07-26. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Nancy H. Dupree (1973): An Historical Guide To Afghanistan, Chapter 3 Sites in Perspective.

- ↑ "Afghanistan: A Treasure Trove for Archaeologists". Time Magazine. 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 2013-07-26. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ↑ The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity by George Erdosy, p.321

- ↑ The History of Afghanistan by Meredith L. Runion, p.44-49

- ↑ Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan, Pre-Islamic Period, by Craig Baxter (1997).

- ↑ Bryant, Edwin F. (2001) The quest for the origins of Vedic culture: the Indo-Aryan migration debate Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513777-4.

- ↑ Afghanistan: ancient Ariana (1950), Information Bureau, p3.

- ↑ M. Witzel, "The Vīdẽvdaδ list obviously was composed or redacted by someone who regarded Afghanistan and the lands surrounding it as the home of all Indo-Iranians (airiia), that is of all (eastern) Iranians, with Airiianem Vaẽjah as their center." page 48, "The Home Of The Aryans", Festschrift J. Narten = Münchener Studien zur Sprachwissenschaft, Beihefte NF 19, Dettelbach: J.H. Röll 2000, 283–338. Also published online, at Harvard University (LINK)

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan, Achaemenid Rule, ca. 550-331 B.C.

- ↑ "Chronological History of Afghanistan – the cradle of Gandharan civilisation". Gandhara.com.au. 15 February 1989. Archived from the original on 2013-07-27. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ↑ "Afghanistan: Achaemenid dynasty rule, Ancient Classical History". Ancienthistory.about.com. 13 April 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-12-30. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ↑ Nancy H. Dupree, An Historical Guide to Kabul Archived July 27, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 "Country Profile: Afghanistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. August 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ The History of Afghanistan by Meredith L. Runion, p.44

- ↑ Dani, A. H. and B. A. Litvinsky. "The Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom". In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Litvinsky, B.A., ed., 1996. UNESCO Publishing, pp. 103–118. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- ↑ Zeimal, E. V. "The Kidarite Kingdom in Central Asia". In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Litvinsky, B.A., ed., 1996, UNESCO Publishing, pp. 119–133. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- ↑ Litvinsky, B. A. "The Hephthalite Empire". In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Litvinsky, B.A., ed., 1996, UNESCO Publishing, pp. 135–162. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- ↑ "Khorasan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 3 October 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ↑ "Khurasan". The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. 2009. p. 55. Archived from the original on 2014-02-09.

In pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, the term "Khurassan" frequently had a much wider denotation, covering also parts of what are now Soviet Central Asia and Afghanistan

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Ibn Battuta (2004). Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325–1354 (reprint, illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 416. ISBN 978-0-415-34473-9. Archived from the original on 2014-04-05.

- ↑ Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah (1560). "Chapter 200: Translation of the Introduction to Firishta's History". The History of India 6. Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 8. Archived from the original on 2013-07-26. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ↑ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad Babur (1525). "Events Of The Year 910 (p.4)". Memoirs of Babur. Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 2014-04-05. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ↑ "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Archived from the original on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ↑ ?amd-Allah Mustawfi of Qazwin (1340). "The Geographical Part of the NUZHAT-AL-QULUB". Translated by Guy Le Strange. Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 2013-07-26. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ "A.—The Hindu Kings of Kábul (p.3)". Sir H. M. Elliot. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1867–1877. Archived from the original on 2013-07-26. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ↑ ""Ghaznavid Dynasty", History of Iran, Iran Chamber Society". Iranchamber.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ↑ Meher, Jagmohan: Afghanistan: Dynamics of Survival, p. 29, at Google Books

- ↑ International Business Publiction: Afghanistan. Country Studiy Guidy, Volume 1, Strategic Information and Developments, p. 66, at Google Books

- ↑ Gupta, Om: Encyclopaedia of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, p. 1444, at Google Books

- ↑ "Central Asian world cities". Faculty.washington.edu. 29 September 2007. Archived from the original on 2013-07-23. Retrieved 6 May 2012.