Adirondack Park

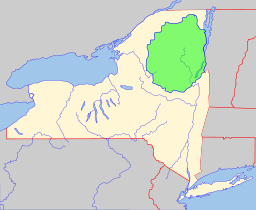

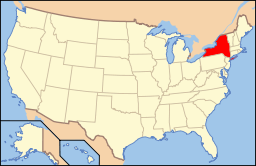

The Adirondack Park is a publicly protected, elliptical area encompassing much of the northeastern lobe of Upstate New York, United States. It is the largest park and the largest state-level protected area in the contiguous United States, and the largest National Historic Landmark.

The park covers some 6.1 million acres (2.5×106 ha), a land area roughly the size of Vermont and greater than the areas of the National Parks of Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, Glacier, and Great Smoky Mountains combined.[3]

Once a hunting ground for numerous Native American tribes, the land that makes up the Park was surrendered to the U.S. Government as a result of the American Revolution in 1783. The events leading up to the creation of the Park were a coordinated effort on both private and public fronts that aimed to transform and protect the land; comparable to, yet different from other national parks like Yellowstone and Yosemite. Known as "the most advanced experiment in conservation in the United States", the Adirondack Park was created in 1892 to protect vital natural resources, most notably freshwater and timber.[4] Although the park is legally protected, controversy exists in terms of what to do with the land, as 60% of the park’s six million acres is privately owned.[5]

This struggle to conserve the land and balance exploitation and conservation originated from philosophies and arguments presented in George Perkins Marsh's work “Man and Nature” that highlight the negative impacts of civilization and humans in general. These conflicting ideals led to the parks creation, development of tourism, logging regulations, and the furthering both of conservation as a political movement and the debate on how the land should be best used. Today, in fact, private organizations are buying land in order to sell it back to New York State to be added to the public portion of Park.[6]

History

Early history

Native American Tribes, such as the Iroquois, Huron, Algonquian people, and Mohawk people, scarcely inhabited the Adirondack Mountains for most of the 1500-1700s, fighting for control of the land mostly for hunting purposes. Although there is evidence to support European contact with natives through the fishing industry, the first recorded European contact with a native group was a French explorer by the name Jacques Cartier in 1534.[7] The number of disputes between native groups, specifically the Iroquois and their largest enemy the Algonquin, increased due to the establishment of the Native American-European fur trade.[8] The fur trade came to be as the result contact between European cod fishermen and natives on the Gulf of the Saint Lawrence River.[9] The constant fighting in conjunction with the short summers and harsh winters, resulted in very few permanent structures or settlements by any native group in the Adirondacks.[10] The vast majority of the Adirondack Mountains are within the bounds of the traditional territory of the Mohawk First Nation until at least 1720. A sedentary agrarian democratic society before Contact, they controlled the eastern part of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy or Six Nations. Although the Confederacy was divided, most of the Iroquois sided with the British during the American Revolution. After the war, most of the Iroquois land which fell within the American border was forcefully signed over through treaties or seized outright. During the 19th century, the U.S. Government forced most of the Iroquois off their traditional territory into reservations in the Midwest. Many escaped to Canada, where they were granted land in the British colony of Upper Canada, modern day Ontario. The resulting land obtained by the U.S. Government was redistributed among investors from New York.[11] Most of the land that makes up the park today was bought in one large purchase by a speculator group, who got the land for just eight cents an acre.[12]

Logging, watershed, and rise of conservation

With the end of the Civil War and the start of the Reconstruction Era, economic expansion required an ever-increasing need for lumber. Although logging in the Adirondacks had been occurring for decades before Reconstruction, it was on a much smaller scale than that of the years after the Civil War.[13] As more and more trees were removed to satisfy the need for lumber, this left barren forest areas with mounds of bark and brush, which resulted in rapid runoff and forest fires. The most extensive logging occurred in the southern portion of the Adirondacks, which meant that the topsoil runoff directly fed into the Hudson River and Erie Canal.[13] Logging that once went unnoticed, now began to affect watersheds of New York City and would grab the attention of many.

One of the earliest notable conservationists was Verplanck Colvin. Born and raised in Albany, his love for the Adirondacks from a young age spurred him to argue the need for conservation, eventually resulting in his work being published in 1872. His argument or main point was to protect the forests in order to preserve the watersheds of New York. This notion of deforestation resulting in runoff and ultimately decreased agricultural and economic opportunity seems to originate from George Perkins Marsh's Man and Nature, published in 1864.[13]

In 1869, a man by the name William Henry Harrison Murray, a Boston pastor, published a wilderness guidebook of the Adirondacks that depicted the Adirondacks as a place of relaxation and pleasure rather than a natural obstacle. With this idea in mind, along with Murray's guidebook, and a record drought in 1883, New York City residents began to leave in large numbers to find escape from the heat and hectic city life in the Adirondacks.[4][14]

The same drought that caused tourists to leave New York City also caused politicians to take action to preserve the freshwater sources provided by the Adirondacks. The New York Board of Trade and New York Chamber of Commerce helped push for state management of timber and watersheds, ultimately resulting in the passing of a law by the New York legislature in 1883 that prohibited future sales of Adirondack state lands.[4]

Park creation

The thinking that led to the creation of the park first appeared in George Perkins Marsh's Man and Nature.[15] Marsh argued that deforestation could lead to desertification: referring to the clearing of once lush lands surrounding the Mediterranean, he asserted "the operation of causes set in action by man has brought the face of the earth to a desolation almost as complete as that of the moon."[16]

The idea for the park itself first occurred to surveyor Verplanck Colvin in 1870, while taking in the view from atop Seward Mountain. He wrote to the state government that action was necessary to protect the forests or it would be wasted, which would lead to the drying up of the water needed to keep the Erie Canal in operation.[17] Three years later he was appointed to a committee formed to consider how to do this.

While his term 'Adirondack Park' led to some derision and fears from longtime residents of the area that they might be bought out and evicted, proponents of the idea began to use 'Adirondack Forest Preserve' instead. Both terms continue in use to this day, with the former referring to the land inside the Blue Line and the latter to that portion owned by the state.

In 1878, Seneca Ray Stoddard produced a topographical survey of the Adirondacks that was influential in the creation of the Park.

Although the motivation for creating the Park was to preserve and conserve the wilderness and innate nature, there existed a debate as to what nature was and what role it played in the lives of humans.[18] Opinions and works from the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Thomas Cole, Herbert Spencer, and Henry William Herbert contributed to the idea of nature being something man can influence and with practice, even control.[18] Whether the creation of the Park was inherently natural was controversial to some degree, in that nature or even wilderness can be thought of as a human construct and not the original and pristine form we consider it to be today.[19]

Serious efforts to protect this land began in 1882, when businessmen in New York began to be concerned about the effects of widespread logging. Without trees, the many steep slopes on the mountains in the region were likely to erode, and the silt from the slopes could conceivably have silted up the Erie Canal and the Hudson itself, choking off New York State’s economic backbone.

In 1885, legislation, signed by Governor David B. Hill, declared that the land in the Adirondack Park and the Catskill Park was to be conserved and never put up for sale or lease. With the increase in tourism, along with the precedence set by the creation of Yellowstone and Yosemite, over two million acres of publicly owned land was deemed the Adirondack Park; established in 1892 by state legislature and further protected with changes in New York’s constitution to keep the land and lumber of the park free from being leased, sold, or purchased privately or publicly.[20] The park was established in 1892, due to the activities of Colvin and other conservationists, including those affiliated with the Northwoods Walton Club.[21] The park was given state constitutional protection in 1894, so that the state-owned lands within its bounds would be protected forever ('forever wild'). The part of the Adirondack Park under government control is referred to as the Adirondack Forest Preserve. Further, this became a National Historic Landmark in 1963.[1][22]

Comparison of the Park in 1900 and 2000

| Year: |

1900 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|

| Area of the Park | 2,800,000 acres (1,100,000 ha) | 6,000,000 acres (2,400,000 ha) |

| State-owned area | 1,200,000 acres (490,000 ha) (43%) | 2,400,000 acres (970,000 ha) (40%) |

| Travel time, New York City to Old Forge | 6.5 hours by railroad | 5 hours by car |

| Permanent park residents | 100,000 | 130,000 |

| Length of public road in the park | 4,154 miles (6,685 km) plus 500 miles (800 km) of passenger railroad track | 6,970 miles (11,220 km) |

| Industry | 92 sawmills, 15 iron mines, 10 pulp/paper mills | 40 sawmills |

Data compiled by the Adirondack Museum, Blue Mountain Lake, New York

Wildlife, hunting, and ecological impact

Tribes such as the Algonquian people and Iroquois have historically hunted in the St.Lawrence River Valley as well as throughout the Adirondacks.[23] Upon the Europeans making contact with Native Americans and establishing a lasting fur trade, there was a rapid increase in the hunting and trapping of animals such as the beaver in order to meet the growing demand for furs.[24] This growing demand led to several battles involving both the Algonquian and Iroquois to obtain beaver pelts in order to trade for European goods and ultimately led to the near extinction of beavers in 1893.[25] Other species, such as the moose, the wolf, and the mountain lion were hunted either for their meat, for sport, or because they were seen as a threat to livestock.[25] Reintroduction efforts for the beaver began around 1904 by combining the remaining beavers in the Adirondacks with those of Canada and later on those from Yellowstone[26] The population quickly grew to around 2000 roughly ten years and around 20,000 in 1921 with the addition of beaver in different areas of the Park.[26] Although this reintroduction was marked as a success, the elevated beaver population was found to have negative economic impacts on waterways and timber sources.[26] The trend of man attempting to manage nature would continue with the introduction of elk to the Adirondacks, a species that is unclear to have ever previously occupied the region.[27]

After two previously failed attempts to introduce elk, in 1903 over 150 elks were reported by the State of New York Forest, Fish, and Game Commission to have been released and surviving in the Park.[28] The elk population would increase for several years only to decline due to illegal hunting practices.[29] In order to protect and maintain the elk population in the future, the DeBar Mountain Game Refuge was established by the State within the Forest Preserve.[30] It should be noted that this act of preserving the species was motivated for hunting purposes rather than an ecological or natural aspect.[31] The Game Refuge was defined by a wire fence, numerous postings, and caretakers employed by the State.[31] This effort to control nature was also observed in the actions of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), work crews who established access roads and water supply expansion.[31] A negative result of the CCC coming to the Park was their trapping and killing of "vermin", which were animals such as hawks, owls, fox, and weasels that preyed on other species sought after by hunters and fishermen.[31] This proved to have unanticipated ecological consequences, most notably the overpopulation of deer which was reported by the New York State Conservation Department in 1945.[31]

Today

Ongoing efforts have been made to reintroduce native fauna that had been lost in the park during earlier exploitation. Animals in various stages of reintroduction include the American beaver, the fisher, the American marten, the moose, the Canadian lynx, and the osprey. Not all of these restoration efforts have been successful yet. There are 53 known species of mammals that live in the park.[32]

The park has a year-round population of about 130,000 people in dozens of villages and hamlets. Seasonal residents number about 200,000, while an estimated 7-10 million tourists visit the park annually. It is estimated that 84 million people live within a day's drive of the park.[33]

In terms of native groups still in existence, the largest is the Mohawk Nation, numbering around 125,000, who today live mostly north of the Saint Lawrence River in Canada however, along with the other member nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.[34]

There are more than 3,000 lakes and 30,000 miles (48,000 km) of streams and rivers. Many areas within the park are devoid of settlements and distant from usable roads. The park includes over 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of hiking trails; these trails comprise the largest trail system in the nation.[33] With its combination of private and public lands, its large scale and its long history as a place people have tried to coexist with nature, many see the Adirondacks as a model for the ways natural areas with human populations can be protected into the future. There are parks in India and other countries that use the Adirondacks concept.

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) is responsible for the care, custody, and management of the 2.7 million acres (1.1×106 ha) of public (state) land in the Adirondack Forest Preserve. The Adirondack Park Agency (APA, created 1971) is a governmental agency that performs long-range planning for the future of the Adirondack State Park. It oversees development plans of private land-owners, as well as activities within the Forest Preserve. Development by private owners must be reviewed to determine if their plan is compatible with the park.

This system of management is distinctly different from New York's state park system, which is managed by different agencies, primarily the state's Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. While it is frequently referred to as a state park, the Adirondack Park has much more in common with a national forest: it mixes private and public land and has year-round residents within its boundaries in long-established settlements. 'Adirondack Park' was Verplanck Colvin's original term for the area; it and the park itself predate by several decades the formal establishment of state parks in New York.

In addition to state agencies (the DEC and APA) responsible for the park, a number of private organizations ([NGOs]) attempt to ensure the Park is preserved for the long term. The largest of these is the Adirondack Council, founded in 1975. Other conservation organizations include Adirondack Wild: Friends of the Forest Preserve, Protect the Adirondacks!, and the Adirondack Chapter of the Nature Conservancy.

Recent Developments

On September 18, 2008, The Nature Conservancy purchased Follensby Pond - about 14,600 acres (5,900 ha) of private land inside the park boundary - for $16 million.[6] The group plans on selling the land to the state which will add it to the forest preserve once the remaining leases for recreational hunting and fishing on the property expire.[6]

Recreation

The Adirondack Park offers a variety of recreational activities which can further explored in Tourism and recreation in the Adirondack Mountains.

Museums

There are two major museums that interpret the region. The Adirondack Museum contains extensive collections about the human settlement of the park while The Wild Center is dedicated to the natural world of the Adirondacks.

Accessibility

The southern side of the park is closer to major population centers, and lies just north of the New York State Thruway (Interstate 90). Interstate 87 (the Adirondack Northway) traverses the eastern side of the park between the Capital District of New York and Montreal, Canada. The northern and western portions of the park are somewhat more remote, but can be reached from Interstate 81, NY 3, NY 28, and US 11. The park is also served by the Adirondack Regional Airport, Amtrak's Adirondack Route along the shores of Lake Champlain, the Adirondack Scenic Railroad from Utica to Old Forge, and the Saratoga and North Creek Railroad. Plattsburgh International Airport, is situated just a few miles outside of the parks eastern boundary in Plattsburgh, NY and offers easy access as well. Centrally located between major populations in the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada, it is estimated that at least 100 million people live within a 10-hour drive from the park.

Golf courses

Golf courses within the park border include the Ausable Club and the Lake Placid Club.

See also

- Adirondack Mountains

- Adirondack Museum

- Adirondack Park Visitor Information Center

- The Wild Center

- List of Wilderness Areas in the Adirondack Park

- List of New York state parks

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Adirondack Forest Preserve". National Park Service. 2007-11-01.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23.

- ↑ "Largest Park Area in the Contiguous US Remains Open to Visitors". Regional Office of Sustainable Tourism / Lake Placid CVB. October 3, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Jacoby 2001, p.16

- ↑ Graham 1978, xii.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Martin Espinoza (2008-09-18). "Conservancy Buys Slice of Adirondacks". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ↑ Sulavik 2005, p.21

- ↑ Sulavik 2005, p. 50

- ↑ Sulavik 2005, p. 51

- ↑ Jacoby 2001, p.20

- ↑ Graham 1978, p.7.

- ↑ Graham 1978, p.6

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Terrie 1993, p.135

- ↑ Perrottet 2013, p.68.

- ↑ Terrie, Phillip G., Contested Terrain; A New History of Nature and People in the Adirondacks, Syracuse: Adirondack Museum/Syracuse University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-8156-0904-9.

- ↑ Schneider, Paul, The Adirondacks, A History of America's First Wilderness, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1997. ISBN 978-0-8050-3490-5.

- ↑ Webb, Nina H., Footsteps through the Adirondacks, The Verplanck Colvin Story, Utica: North Country Books, 1996. ISBN 0-925168-50-5.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Jacoby 2001, p.12

- ↑ Cronon 1995, p.1

- ↑ Graham 1978, p.124.

- ↑ Nash, Roderick F. 2001. Wilderness and the American Mind, 4th ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, p.117.

- ↑ Richard Greenwood (February 7, 1976). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Adirondack Forest Preserve" (PDF). National Park Service.

- ↑ Harris 2012, p.99

- ↑ Harris 2012, p.100

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Harris 2012, p.101

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Harris 2012, p.102

- ↑ Harris 2012, p. 107

- ↑ Harris 2012, p.107

- ↑ Harris 2012, p.108

- ↑ Harris 2012, p.110

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Harris 2012, p.111

- ↑ "SUNY-ESF: Adirondack Ecological Center". Esf.edu. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Adirondack Park Agency - Maps & Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

- ↑ De Capua, Sarah. The IroquoisPublished by Marshall Cavendish, 2006. ISBN 0-7614-1896-2, ISBN 978-0-7614-1896-2

Notes

- Cronon, William. 1996. "The Trouble with Wilderness: A Response." Environmental History 1, no. 1 : 47.

- Graham, Frank, and Ada Graham. 1978. The Adirondack Park: a political history. New York: Knopf.

- Harris, Glenn. 2012. An environmental history of New York's north country: the Adirondack Mountains and the St. Lawrence River Valley : case studies and neglected topics. Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press.

- Jacoby, Karl. 2001. Crimes against nature: squatters, poachers, thieves, and the hidden history of American conservation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Perrottet, T. 2013. "Birthplace of the American Vacation Escape to the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York, a breath of fresh air for harried city dwellers since the Gilded Age". SMITHSONIAN. 44 (1): 68.

- Sulavik, Stephen. 2005. Adirondack: of Indians and mountains, 1535-1838. Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press.

- Terrie, Philip G. 1993. ""Imperishable Freshness": Culture, Conservation, and the Adirondack Park." Forest & Conservation History 37, no. 3: 132-141.

External links

- The Adirondack Museum

- Adirondackhistory.org: A Central Park for the World

- The Adirondack Lakes Center for the Arts

- The Adirondack Mountain Club

- Protect the Adirondacks!

- The Adirondack Council

- New York Department of Environmental Conservation

- Pure Adirondacks — guide to the Adirondack Experience.

- The Wild Center

- The Wildlife Conservation Society's Adirondack Program

- Adirondack Journal of Environmental Studies

Media related to Photographs by Anne LaBastille at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Photographs by Anne LaBastille at Wikimedia Commons

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adirondack Park. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Adirondacks. |

Coordinates: 44°00′N 74°20′W / 44.000°N 74.333°W

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||