Adiabatic process

| Thermodynamics | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The classical Carnot heat engine | ||||||||||||

|

Branches |

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Book:Thermodynamics | ||||||||||||

An adiabatic process is one that occurs without transfer of heat or matter between a system and its surroundings.[1][2] The adiabatic process provides a rigorous conceptual basis for the theory used to expound the first law of thermodynamics, and as such it is a key concept in thermodynamics.

Some chemical and physical processes occur so rapidly that they may be conveniently described by the "adiabatic approximation", meaning that there is not enough time for the transfer of energy as heat to take place to or from the system.[3]

In way of example, the adiabatic flame temperature is an idealization that uses the "adiabatic approximation" so as to provide an upper limit calculation of temperatures produced by combustion of a fuel. The adiabatic flame temperature is the temperature that would be achieved by a flame if the process of combustion took place in the absence of heat loss to the surroundings.

Description

A process that does not involve the transfer of heat into or out of a system, so that Q = 0, is called an adiabatic process, and such a system is said to be adiabatically isolated (perfectly insulated). The assumption that a process is adiabatic is a frequently made simplifying assumption. For example, the compression of a gas within a cylinder of an engine is assumed to occur so rapidly that on the time scale of the compression process, little of the system's energy can be transferred out as heat. Even though the cylinders are not insulated and are quite conductive, that process is idealized to be adiabatic.

The assumption of adiabatic isolation of a system is a useful one, and is often combined with others so as to make the calculation of the system's behaviour possible. Such assumptions are idealizations. The behaviour of actual machines deviates from these idealizations, but the assumption of such "perfect" behaviour provide a useful first approximation of how the real world works.

Various applications of the adiabatic assumption

- If the system has rigid walls such that work cannot be transferred in or out (W = 0), and the walls of the system are not adiabatic and energy is added in the form of heat (Q > 0), the temperature of the system will rise.

- If the system has rigid walls such that work cannot be added (W = 0), and the system boundaries are adiabatic (Q = 0), but energy is added as work in the form of friction or the stirring of a viscous fluid within the system, the temperature of the system will rise.

- If the system walls are adiabatic (Q = 0), but not rigid (W ≠ 0), and energy is added to the system in the form of frictionless, non-viscous work, the temperature of the system will rise. The energy added is stored within the system, and is completely recoverable as work. Such a process of the frictionless, non-viscous application of work to a system is called an isentropic process. If the system contains a compressible gas and is reduced in volume, the uncertainty of the position of the gas is reduced as it is compressed to a smaller volume, and seemingly reduces the entropy of the system, but the temperature of the system will rise as the process is isentropic (ΔS = 0). Should the work be added in such a way that friction or viscous forces are operating within the system, the process is not isentropic, the temperature of the system will rise, and the work added to the system is not entirely recoverable in the form of work.

- If the walls of a system are not adiabatic, and energy is transferred in as heat, entropy is transferred into the system with the heat. Such a process is neither adiabatic nor isentropic, having Q > 0, and ΔS > 0 according to the second law of thermodynamics.

Naturally occurring adiabatic processes are irreversible (entropy is produced).

The transfer of energy as work into an adiabatic (insulated) system can be imagined as being of two idealized extreme kinds. One kind of work is where there is no entropy produced within the system (no friction, viscous dissipation, etc), and the work is only pressure-volume work (denoted by P dV). In nature, this ideal kind occurs only approximately, because it demands an infinitely slow process and no sources of dissipation.

The other extreme kind of work is isochoric work (dV = 0), for which energy is added as work solely through friction or viscous dissipation within the system. A stirrer that transfers energy to a viscous fluid of an adiabatically isolated system with rigid walls will cause a rise in temperature of the fluid, but that work is not recoverable. Isochoric work is irreversible.[4] The second law of thermodynamics observes that a natural process of transfer of energy as work, always consists at least of isochoric work and often both of these extreme kinds of work. Every natural process, adiabatic or not, is irreversible, with ΔS > 0, as friction or viscosity are always present to some extent.

Adiabatic heating and cooling

The adiabatic compression of a gas causes a rise in temperature of the gas. Adiabatic expansion against pressure, or a spring, causes a drop in temperature. In contrast, free expansion is an isothermal process for an ideal gas.

Adiabatic heating occurs when the pressure of a gas is increased from work done on it by its surroundings, e.g., a piston compressing a gas contained within an adiabatic cylinder. This finds practical application in Diesel engines which rely on the lack of quick heat dissipation during their compression stroke to elevate the fuel vapor temperature sufficiently to ignite it.

Adiabatic heating occurs in the Earth's atmosphere when an air mass descends, for example, in a katabatic wind, Foehn wind, or chinook wind flowing downhill over a mountain range. When a parcel of air descends, the pressure on the parcel increases. Due to this increase in pressure, the parcel's volume decreases and its temperature increases as work is done on the parcel of air, thus increasing the internal energy. The parcel of air is unable to dissipate energy as heat, hence it is considered adiabatically isolated, and its temperature will rise sensibly.

Adiabatic cooling occurs when the pressure on an adiabatically isolated system is decreased, allowing it to expand, thus causing it to do work on its surroundings. When the pressure applied on a parcel of air is reduced, the air in the parcel is allowed to expand; as the volume increases, the temperature falls as internal energy decreases. Adiabatic cooling occurs in the Earth's atmosphere with orographic lifting and lee waves, and this can form pileus or lenticular clouds.

Adiabatic cooling does not have to involve a fluid. One technique used to reach very low temperatures (thousandths and even millionths of a degree above absolute zero) is adiabatic demagnetisation, where the change in magnetic field on a magnetic material is used to provide adiabatic cooling. Also, the contents of an expanding universe can be described (to first order) as an adiabatically cooling fluid. (See - Heat death of the universe)

Rising magma also undergoes adiabatic cooling before eruption, particularly significant in the case of magmas that rise quickly from great depths such as kimberlites.[5]

Such temperature changes can be quantified using the ideal gas law, or the hydrostatic equation for atmospheric processes.

In practice, no process is truly adiabatic. Many processes rely on a large difference in time scales of the process of interest and the rate of heat dissipation across a system boundary, and thus are approximated by using an adiabatic assumption. There is always some heat loss, as no perfect insulators exist.

Ideal gas (reversible process)

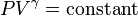

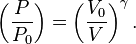

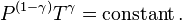

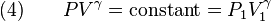

The mathematical equation for an ideal gas undergoing a reversible (i.e., no entropy generation) adiabatic process is

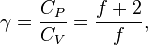

where P is pressure, V is volume, and

being the specific heat for constant pressure,

being the specific heat for constant pressure,

being the specific heat for constant volume,

being the specific heat for constant volume,  is the adiabatic index, and

is the adiabatic index, and  is the number of degrees of freedom (3 for monatomic gas, 5 for diatomic gas and collinear molecules e.g. carbon dioxide).

is the number of degrees of freedom (3 for monatomic gas, 5 for diatomic gas and collinear molecules e.g. carbon dioxide).

For a monatomic ideal gas,  , and for a diatomic gas (such as nitrogen and oxygen, the main components of air)

, and for a diatomic gas (such as nitrogen and oxygen, the main components of air)  .[6] Note that the above formula is only applicable to classical ideal gases and not Bose–Einstein or Fermi gases.

.[6] Note that the above formula is only applicable to classical ideal gases and not Bose–Einstein or Fermi gases.

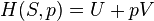

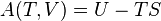

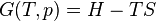

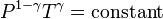

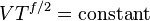

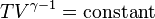

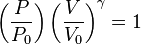

For reversible adiabatic processes, it is also true that

where T is an absolute temperature. This can also be written as

Example of adiabatic compression

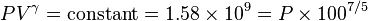

Let's now look at a common example of adiabatic compression- the compression stroke in a gasoline engine. We will make a few simplifying assumptions: that the uncompressed volume of the cylinder is 1000 cm3 (one litre), that the gas within is nearly pure nitrogen (thus a diatomic gas with five degrees of freedom and so  = 7/5), and that the compression ratio of the engine is 10:1 (that is, the 1000 cm3 volume of uncompressed gas will compress down to 100 cm3 when the piston goes from bottom to top). The uncompressed gas is at approximately room temperature and pressure (a warm room temperature of ~27 ºC or 300 K, and a pressure of 1 bar ~ 100 kPa, or about 14.7 PSI, i.e. typical sea-level atmospheric pressure).

= 7/5), and that the compression ratio of the engine is 10:1 (that is, the 1000 cm3 volume of uncompressed gas will compress down to 100 cm3 when the piston goes from bottom to top). The uncompressed gas is at approximately room temperature and pressure (a warm room temperature of ~27 ºC or 300 K, and a pressure of 1 bar ~ 100 kPa, or about 14.7 PSI, i.e. typical sea-level atmospheric pressure).

so our adiabatic constant for this experiment is about 1.58 billion.

The gas is now compressed to a 100 cm3 volume (we will assume this happens quickly enough that no heat can enter or leave the gas). The new volume is 100 cm3, but the constant for this experiment is still 1.58 billion:

so solving for P:

or about 362 PSI or 24.5 atm. Note that this pressure increase is more than a simple 10:1 compression ratio would indicate; this is because the gas is not only compressed, but the work done to compress the gas has also heated the gas and the hotter gas will have a greater pressure even if the volume had not changed.

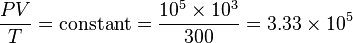

We can solve for the temperature of the compressed gas in the engine cylinder as well, using the ideal gas law. Our initial conditions are 100,000 pa of pressure, 1000 cm3 volume, and 300 K of temperature, so our experimental constant is:

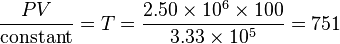

We know the compressed gas has V = 100 cm3 and P = 2.50E6 pascals, so we can solve for temperature by simple algebra:

That is a final temperature of 751 K, or 477 °C, or 892 °F, well above the ignition point of many fuels. This is why a high compression engine requires fuels specially formulated to not self-ignite (which would cause engine knocking when operated under these conditions of temperature and pressure), or that a supercharger and intercooler to provide a lower temperature at the same pressure would be advantageous. A diesel engine operates under even more extreme conditions, with compression ratios of 20:1 or more being typical, in order to provide a very high gas temperature which ensures immediate ignition of injected fuel.

Adiabatic free expansion of a gas

For an adiabatic free expansion of an ideal gas, the gas is contained in an insulated container and then allowed to expand in a vacuum. Because there is no external pressure for the gas to expand against, the work done by or on the system is zero. Since this process does not involve any heat transfer or work, the First Law of Thermodynamics then implies that the net internal energy change of the system is zero. For an ideal gas, the temperature remains constant because the internal energy only depends on temperature in that case. Since at constant temperature, the entropy is proportional to the volume, the entropy increases in this case, therefore this process is irreversible.

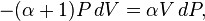

Derivation of P-V relation for adiabatic heating and cooling

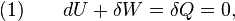

The definition of an adiabatic process is that heat transfer to the system is zero,  . Then, according to the first law of thermodynamics,

. Then, according to the first law of thermodynamics,

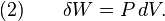

where dU is the change in the internal energy of the system and δW is work done by the system. Any work (δW) done must be done at the expense of internal energy U, since no heat δQ is being supplied from the surroundings. Pressure-volume work δW done by the system is defined as

However, P does not remain constant during an adiabatic process but instead changes along with V.

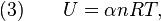

It is desired to know how the values of dP and dV relate to each other as the adiabatic process proceeds. For an ideal gas the internal energy is given by

where  is the number of degrees of freedom divided by two, R is the universal gas constant and n is the number of moles in the system (a constant).

is the number of degrees of freedom divided by two, R is the universal gas constant and n is the number of moles in the system (a constant).

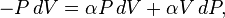

Differentiating Equation (3) and use of the ideal gas law,  , yields

, yields

Equation (4) is often expressed as  because

because  .

.

Now substitute equations (2) and (4) into equation (1) to obtain

factorize : :

:

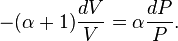

and divide both sides by PV:

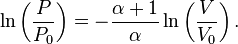

After integrating the left and right sides from  to V and from

to V and from  to P and changing the sides respectively,

to P and changing the sides respectively,

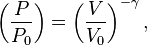

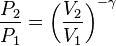

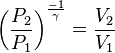

Exponentiate both sides, and substitute  with

with  , the heat capacity ratio

, the heat capacity ratio

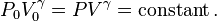

and eliminate the negative sign to obtain

Therefore,

and

Derivation of T-V relation for adiabatic heating and cooling

Substituting the ideal gas law into the above, we obtain

which simplifies to

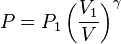

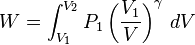

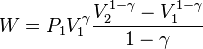

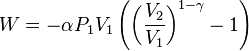

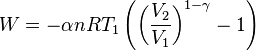

Derivation of discrete formula

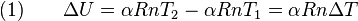

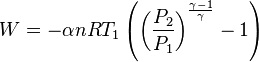

The change in internal energy of a system, measured from state 1 to state 2, is equal to

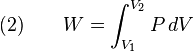

At the same time, the work done by the pressure-volume changes as a result from this process, is equal to

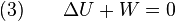

Since we require the process to be adiabatic, the following equation needs to be true

By the previous derivation,

Rearranging (4) gives

Substituting this into (2) gives

Integrating,

Substituting  ,

,

Rearranging,

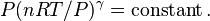

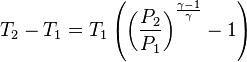

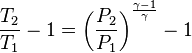

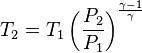

Using the ideal gas law and assuming a constant molar quantity (as often happens in practical cases),

By the continuous formula,

Or,

Substituting into the previous expression for  ,

,

Substituting this expression and (1) in (3) gives

Simplifying,

Simplifying,

Simplifying,

Graphing adiabats

An adiabat is a curve of constant entropy on the P-V diagram. Some properties of adiabats on a P-V diagram are indicated. These properties may be read from the classical behaviour of ideal gases, except in the region where PV becomes small (low temperature), where quantum effects become important.

- Every adiabat asymptotically approaches both the V axis and the P axis (just like isotherms).

- Each adiabat intersects each isotherm exactly once.

- An adiabat looks similar to an isotherm, except that during an expansion, an adiabat loses more pressure than an isotherm, so it has a steeper inclination (more vertical).

- If isotherms are concave towards the "north-east" direction (45 °), then adiabats are concave towards the "east north-east" (31 °).

- If adiabats and isotherms are graphed at regular intervals of entropy and temperature, respectively (like altitude on a contour map), then as the eye moves towards the axes (towards the south-west), it sees the density of isotherms stay constant, but it sees the density of adiabats grow. The exception is very near absolute zero, where the density of adiabats drops sharply and they become rare (see Nernst's theorem).

The following diagram is a P-V diagram with a superposition of adiabats and isotherms:

The isotherms are the red curves and the adiabats are the black curves.

The adiabats are isentropic.

Volume is the horizontal axis and pressure is the vertical axis.

Etymology

The term adiabatic/ˌædiəˈbætɪk/, literally means 'not to be passed through'. It is formed from the ancient Greek privative "α" ("not") + διαβατός, "able to be passed through", in turn deriving from διὰ- ("through"), and βαῖνειν ("to walk, go, come"), thus ἀδιάβατος .[7] According to Maxwell,[8] and to Partington,[9] the term was introduced by Rankine.[10]

The etymological origin corresponds here to an impossibility of transfer of energy as heat and of transfer of matter across the wall.

Divergent usages of the word adiabatic

This present article is written from the viewpoint of macroscopic thermodynamics, and the word adiabatic is used in this article in the traditional way of thermodynamics, introduced by Rankine. It is pointed out in the present article that, for example, if a compression of a gas is rapid, then there is little time for heat transfer to occur, even when the gas is not adiabatically isolated. In this sense, a rapid compression of a gas is sometimes approximately or loosely said to be adiabatic (though often far from isentropic) even when the gas is not adiabatically isolated.

Quantum mechanics and quantum statistical mechanics, however, use the word adiabatic in very a different sense, one that can at times seem almost opposite to the classical thermodynamic sense. In quantum theory, the word adiabatic can mean something perhaps near isentropic, or perhaps near quasi-static, but the usage of the word is very different between the two disciplines.

On one hand in quantum theory, if a perturbative element of compressive work is done almost infinitely slowly (that is to say quasi-statically), it is said to have been done adiabatically. The idea is that the shapes of the eigenfunctions change slowly and continuously, so that no quantum jump is triggered, and the change is virtually reversible. While the occupation numbers are unchanged, nevertheless there is change in the energy levels of one-to-one corresponding, pre-and post-compression, eigenstates. Thus a perturbative element of work has been done without heat transfer and without introduction of random change within the system. For example, Max Born writes "Actually, it is usually the 'adiabatic' case with which we have to do: i.e. the limiting case where the external force (or the reaction of the parts of the system on each other) acts very slowly. In this case, to a very high approximation

that is, there is no probability for a transition, and the system is in the initial state after cessation of the perturbation. Such a slow perturbation is therefore reversible, as it is classically."[11]

On the other hand in quantum theory, if a perturbative element of compressive work is done rapidly, it randomly changes the occupation numbers of the eigenstates, as well as changing their shapes. In that theory, such a rapid change is said not to be 'adiabatic', and the contrary word 'diabatic' is even applied to it. One might guess that perhaps Clausius, if he were confronted with this, in the now-obsolete language he used in his day, would have said that "internal work" was done and that 'heat was generated though not transferred'.

In classical thermodynamics, such a rapid change would still be called adiabatic because the system is adiabatically isolated, and there is no transfer of energy as heat. The strong irreversibility of the change, due to viscosity or other entropy production, does not impinge on this classical usage.

Thus for a mass of gas, in macroscopic thermodynamics, words are so used that a compression is sometimes loosely or approximately said to be adiabatic if it is rapid enough to avoid heat transfer, even if the system is not adiabatically isolated. But in quantum statistical theory, a compression is not called adiabatic if it is rapid, even if the system is adiabatically isolated in the classical thermodynamic sense of the term. The words are used differently in the two disciplines, as stated just above.

See also

- Cyclic process

- First law of thermodynamics

- Heat burst

- Isobaric process

- Isenthalpic process

- Isentropic process

- Isochoric process

- Isothermal process

- Polytropic process

- Entropy (classical thermodynamics)

- Quasistatic process

- Total air temperature

- Magnetic refrigeration

References

- ↑ Carathéodory, C. (1909). Untersuchungen über die Grundlagen der Thermodynamik, Mathematische Annalen, 67: 355–386, doi:10.1007/BF01450409. A translation may be found here. Also a mostly reliable translation is to be found at Kestin, J. (1976). The Second Law of Thermodynamics, Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross, Stroudsburg PA.

- ↑ Bailyn, M. (1994). A Survey of Thermodynamics, American Institute of Physics Press, New York, ISBN 0-88318-797-3, p. 21.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Bailyn, M. (1994), pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Münster, A. (1970), Classical Thermodynamics, translated by E.S. Halberstadt, Wiley–Interscience, London, ISBN 0-471-62430-6, p. 45.

- ↑ Kavanagh, J.L.; Sparks R.S.J. (2009). "Temperature changes in ascending kimberlite magmas". Earth and Planetary Science Letters (Elsevier) 286 (3–4): 404–413. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.286..404K. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.07.011. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ Adiabatic Processes

- ↑ Liddell, H.G., Scott, R. (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon, Clarendon Press, Oxford UK.

- ↑ Maxwell, J.C. (1871), Theory of Heat (first ed.), London: Longmans, Green and Co., p. 129

- ↑ Partington, J.R. (1949), An Advanced Treatise on Physical Chemistry., volume 1, Fundamental Principles. The Properties of Gases, London: Longmans, Green and Co., p. 122.

- ↑ Rankine, W.J.McQ. (1866). On the theory of explosive gas engines, The Engineer, July 27, 1866; at page 467 of the reprint in Miscellaneous Scientific Papers, edited by W.J. Millar, 1881, Charles Griffin, London.

- ↑ Born, M. (1927). Physical aspects of quantum mechanics, Nature, 119: 354–357. (Translation by Robert Oppenheimer.)

- Silbey, Robert J. et al. (2004). Physical chemistry. Hoboken: Wiley. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-471-21504-2.

- Broholm, Collin. "Adiabatic free expansion." Physics & Astronomy @ Johns Hopkins University. N.p., 26 Nov. 1997. Web. 14 Apr. *Nave, Carl Rod. "Adiabatic Processes." HyperPhysics. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2011. .

- Thorngren, Dr. Jane R.. "Adiabatic Processes." Daphne – A Palomar College Web Server. N.p., 21 July 1995. Web. 14 Apr. 2011. .