Adenanthos cuneatus

| Adenanthos cuneatus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Adenanthos |

| Species: | A. cuneatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Adenanthos cuneatus Labill. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Adenanthos flabellifolius Knight | |

Adenanthos cuneatus, also known as coastal jugflower, flame bush, bridle bush and sweat bush, is a shrub of the family Proteaceae native to the south coast of Western Australia. The French naturalist Jacques Labillardière originally described it in 1805. Within the genus Adenanthos, it lies in the section Adenanthos and is most closely related to A. stictus. A. cuneatus has hybridized with four other species of Adenanthos. Growing to 2 m (6 ft 7 in) high and wide, it is erect to prostrate in habit, with wedge-shaped lobed leaves covered in fine silvery hair. The single red flowers are insignificant, and appear all year, though especially in late spring. The reddish new growth occurs over the summer.

It is sensitive to Phytophthora cinnamomi dieback, hence requiring a sandy soil and good drainage to grow in cultivation, its natural habitat of sandy soils in heathland being an example. Its pollinators include bees, honey possum, silvereye and honeyeaters, particularly the western spinebill. A. cuneatus is grown in gardens in Australia and the western United States, and a dwarf and prostrate form are commercially available.

Description

Adenanthos cuneatus grows as an erect, spreading or prostrate shrub to 2 m (6 ft 7 in) high and wide. It has a woody base, known as a lignotuber, from which it can resprout after bushfire. The wedge-shaped (cuneate) leaves are on short petioles, and are 2 cm (0.8 in) long and 1–1.5 cm (0.4–0.6 in) wide, with 3 to 5 (and occasionally up to 7) rounded 'teeth' or lobes at the ends.[1][2] New growth is red and slightly translucent. It glows bright red against the light, especially when the sun is low in the sky.[3] New growth is mainly seen in summer, and the leaves in general are covered with fine, silvery hair. Occurring throughout the year but more often from August to November, the insignificant single flowers are a dull red in colour and measure around 4 cm (1.6 in) long.[1][2] The pollen is triangular in shape and measures 31–44 µm (0.0012–0.0017 in) in length, averaging around 34 µm (0.0013 in).[4]

The species is similar in many ways to its close relative A. stictus. The most obvious difference is in habit: the multi-stemmed, lignotuberous A. cuneatus rarely grows over 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in height, whereas A. stictus is a taller single-stemmed non-lignotuberous shrub that commonly reaches 5 m (16 ft 5 in) in height. Leaves are similar, but the lobes at the leaf apex are regular and crenate (rounded) in A. cuneatus, but irregular and dentate (toothed) in A. stictus.[5] Also, new growth does not have a red flush in A. stictus, and juvenile leaves of A. stictus are usually much larger than adult leaves, a difference not seen in A. cuneatus. The flowers of the two species are very similar, differing only subtly in dimension, colour and indumentum.[6]

Taxonomy

Discovery and naming

Although the precise time and location of its discovery are unknown, Jacques Labillardière, botanist to an expedition under Bruni d'Entrecasteaux, which anchored in Esperance Bay on the south coast of Western Australia on 9 December 1792, most likely collected the first known botanical specimen of Adenanthos cuneatus on 16 December while searching the area between Observatory Point and Pink Lake for the zoologist Claude Riche, who had gone ashore two days earlier and failed to return. Following an unsuccessful search the following day, several senior members of the expedition were convinced that Riche must have perished of thirst or at the hands of the Australian Aborigines and counselled d'Entrecasteaux to sail without him. However, Labillardière convinced d'Entrecasteaux to search for another day, and was rewarded not only with the recovery of Riche, but also with the collection of several highly significant botanical specimens, including the first specimens of Anigozanthos (Kangaroo Paw) and Nuytsia floribunda (West Australian Christmas Tree) and, as aforementioned, A. cuneatus.[7][8]

Thirteen years passed before Labillardière published a formal description of A. cuneatus, and in the meantime several further collections were made: Scottish botanist Robert Brown collected a specimen on 30 December 1801, during the visit of HMS Investigator to King George Sound;[9] and, fourteen months later, Jean-Baptiste Leschenault de La Tour, botanist to Nicolas Baudin's voyage of exploration,[10] and "gardener's boy" Antoine Guichenot[11] collected more specimens therein. The official account of Baudin's expedition contain notes from Leschenault on vegetation:

"Sur les bords de la mer, croissent, en grande abondance, l 'adenanthos cuneata, l 'adenanthos sericea au feuillage velouté, et une espèce du même genre dont les feuilles sont arrondies."[12]("On the seashore, grows, in great abundance, Adenanthos cuneata, the softer-leaved Adenanthos sericea, and a species of the same genus with rounded leaves.")

Labillardière eventually published the genus Adenanthos, along with A. cuneatus and two other species, in his 1805 Novae Hollandiae Plantarum Specimen. He chose the specific name cuneata in reference to the leaves of this species, which are cuneate (triangular).[5][13] This name has feminine gender, consistent with the gender assigned by Labillardière to the genus.[14] He did not designate which of the three published species was to serve as the type species of Adenanthos, but Irish botanist E. Charles Nelson has since chosen A. cuneatus as lectotype for the genus, since the holotype of A. cuneatus bears an annotation showing the derivation of the genus name, and because Labillardière's description of it is the most detailed of the three, and is referred to by the other descriptions.[15]

Synonymy

In 1809, Richard Salisbury, writing under Joseph Knight's name in the controversial On the cultivation of the plants belonging to the natural order of Proteeae, published the name Adenanthes [sic] flabellifolia, listing A. cuneata as a synonym.[16] As no type specimen was given, and no specimen annotated by Knight could be found, this was treated as a nomenclatural synonym of A. cuneata and was therefore rejected on the principle of priority.[17][18]

Also synonymised with this species is Adenanthos crenata, published by Carl Ludwig Willdenow's in Kurt Polycarp Joachim Sprengel's 1825 16th edition of Systema Vegetabilium. Willdenow published both A. cuneata and A. crenata, giving them different descriptions but designating the same type specimen for both.[19] Thus A. crenata was rejected under the principle of priority,[17] and is now regarded as a nomenclatural synonym of A. cuneatus.[20]

Infrageneric placement

In 1870, George Bentham published the first infrageneric arrangement of Adenanthos in Volume 5 of his landmark "Flora Australiensis". He divided the genus into two sections, placing A. cuneata in A. sect. Stenolaema because its perianth tube is straight and not swollen above the middle.[21] This arrangement still stands today, though A. sect. Stenolaema is now renamed to the autonym A. sect. Adenanthos.

A phenetic analysis of the genus undertaken by Nelson in 1975 yielded results in which A. cuneatus was grouped with A. stictus. This pairing was then neighbour to a larger group that included A. forrestii, A. eyrei, A. cacomorphus, A. ileticos, and several hybrid and unusual forms of A. cuneatus.[22] Nelson's analysis supported Bentham's sections, and so they were retained when Nelson published a taxonomic revision of the genus in 1978. He further subdivided A. sect. Adenanthos into two subsections, with A. cuneata placed into A. subsect. Adenanthos for reasons including the length of its perianth,[23] but Nelson discarded his own subsections in his 1995 treatment of Adenanthos, for the Flora of Australia series of monographs. By this time, the ICBN had issued a ruling that all genera ending in -anthos must be treated as having masculine gender; thus the specific epithet became cuneatus.[2]

The placement of A. cuneatus in Nelson's arrangement of Adenanthos may be summarised as follows:[2]

- Adenanthos

- A. sect. Eurylaema (4 species)

- A. sect. Adenanthos

- A. drummondii

- A. dobagii

- A. apiculatus

- A. linearis

- A. pungens (2 subspecies)

- A. gracilipes

- A. venosus

- A. dobsonii

- A. glabrescens (2 subspecies)

- A. ellipticus

- A. cuneatus

- A. stictus

- A. ileticos

- A. forrestii

- A. eyrei

- A. cacomorphus

- A. flavidiflorus

- A. argyreus

- A. macropodianus

- A. terminalis

- A. sericeus (2 subspecies)

- A. × cunninghamii

- A. oreophilus

- A. cygnorum (2 subspecies)

- A. meisneri

- A. velutinus

- A. filifolius

- A. labillardierei

- A. acanthophyllus

Hybrids

Adenanthos cuneatus apparently forms hybrids with other Adenanthos species quite readily, as four putative natural hybrids have been reported:

- A. × cunninghamii (Albany Woollybush), a hybrid between A. cuneatus and A. sericeus, was first collected in 1827, and published as A. cunninghamii in 1845. Other than some dubious collections in the 1830s and 1840s, no further sightings are known to have been made until 1973, when Nelson rediscovered it. At the time it was regarded as a distinct species, but by 1995 it was thought to be a hybrid,[2] and this was confirmed by genetic analysis in 2002.[24] In appearance it is very similar to A. sericeus, but its leaf segments are flat rather than cylindrical.[25]

- A single plant discovered by Nelson near Israelite Bay, where both putative parents are found, is regarded as a hybrid between A. cuneatus and A. dobsonii. Leaves are mostly triangular like those of A. cuneatus, but whereas A. cuneatus leaves are mostly five-lobed, the putative hybrid usually has three lobes, with the occasional leaf being entire like those of A. dobsonii (though A. cuneatis itself occasionally bears entire leaves). Leaves of the putative hybrid lack the thick indumentum of A. cuneatus, being bright green with a sparse indumentum like that of A. dobsonii. Flower colour is like that of A. cuneatus but the style lacks an indumentum, like A. dobsonii.[26]

- Two plants found near Twilight Cove are regarded as hybrids between A. cuneatus and A. forrestii, the only two Adenanthos species to occur in the area. One was discovered by Nelson in 1972, the other by Alex George in 1974. They are about 5 km apart, and differ somewhat. The leaves are triangular and flat like those of A. cuneatus, but the leaves of mature shoots are very long and narrow, and the leaves of younger shoots are deeply lobed.[27]

- In his 1995 revision, Nelson refers to putative hybrids with A. dobsonii and A. apiculatus, citing the 1978 paper in which he published putative hybrids with A. dobsonii and A. forrestii.[2] It is unclear whether the reference to A. apiculatus is an error or a fourth putative hybrid.

Common names

This species has several common names, some highly localised. Two names allude to its consumption by horses; bridle bush, a name used east of Esperance, refers to the fact that horses favour it as fodder; and sweat bush, used around Hopetoun, derived from the claim that horses break out in sweat after consuming young growth. The common name of flame bush derives from the brilliant red new growth. It is also known as coastal jugflower.[1][3][5] Nelson also records the use of the names Templetonia and native temp, but ridicules them as obvious errors.[28]

Distribution and habitat

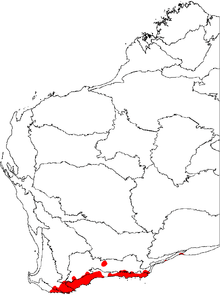

The most widely distributed Adenanthos species of the south coast,[30] A. cuneatus is common and locally abundant between King George Sound and Israelite Bay, along the coast and up to 40 km (25 mi) inland, with isolated populations extending west to Walpole and the Stirling Range, and as far east of Israelite Bay as Twilight Cove.[31]

This species is restricted to siliceous sandplain soils and will not grow in calcareous soils such as the limestone plains of the Nullarbor, or even siliceous dunes with limestone at little depth.[32] This restriction explains the disjunctions east of Israelite Bay: the species occurs only in those few locations where the existence of cliff-top dunes of deep siliceous sand provide suitable habitat.[33] Provided the soil is siliceous and fairly dry, A. cuneatus tolerates a range of edaphic conditions: it grows in both lateritic sand and sands of marine origin,[34] and it tolerates pH levels ranging from 3.8 to 6.6.[35]

Consistent with these edaphic preferences, A. cuneatus is a frequent and characteristic member of the kwongan heathlands commonly found on the sandplains of Southwest Australia.[31] The climate in its range is mediterranean, with annual rainfall from 275 to 1,000 mm (10.8 to 39.4 in).[36]

Ecology

Colletid bees of the genus Leioproctus visit Adenanthos cuneatus flowers.[37] A 1978 field study conducted around Albany found the honey possum (Tarsipes rostratus) occasionally visited Adenanthos cuneatus, while the western spinebill much preferred the species to other flowers.[38] A 1980 field study at Cheyne beach showed that the New Holland honeyeater and white-cheeked honeyeater pollinate it[4] A 1985–86 field study in the Fitzgerald River National Park found that the nectar-feeding honey possum occasionally eats it.[39] The silvereye (Zosterops lateralis) feeds on nectar from the flowers, and has also been observed taking dew-drops from leaves early in the morning.[40]

Adenanthos cuneatus is known to be susceptible to Phytophthora cinnamomi dieback, but reports on the degree of susceptibility vary from low to high.[41] A study of Banksia attenuata woodland 400 km (249 mi) southeast of Perth across 16 years, and following a wave of P. cinnamomi infestation, showed that A. cuneatus populations were not significantly reduced in diseased areas.[42] Phosphite (used to combat dieback) has some toxic effects in A. cuneatus, with some necrosis of leaf tips, but the shrub uptakes little of the compound when compared with other shrubs.[43] Specimens in coastal dune vegetation showed some sensitivity to the fungus Armillaria luteobubalina, with between a quarter and a half of plants exposed succumbing to the pathogen.[44]

Cultivation

Adenanthos cuneatus was taken to Great Britain in 1824, and has been grown in cultivation in Australia[1] and the western United States.[45] Its attractive bronzed or reddish foliage is its main horticultural feature, along with its ability to attract birds to the garden. It requires a well-drained position to do well,[1] but will grow in full sun or semi-shade, and tolerates both sand and gravelly soils. George Lullfitz, a Western Australian nurseryman, recommends growing it as a rambling ground cover in front of other shrubs, or in a rockery.[46]

The following cultivars exist:

- A. "Coral Drift" is a compact form in cultivation since at least the 1990s. It is 50–70 cm (19.7–27.6 in) tall and 1–1.5 m (3.3–4.9 ft) wide. The grey foliage has pinkish purple new growth.[45]

- A. "Coral Carpet" is a prostrate form which peaks at around 20 cm (7.9 in) high and spreads to 1.5 m (4.9 ft) across. The new foliage is a pinkish purple. A chance seedling from 'Coral Drift', it was originally developed by George Lullfitz of Lullfitz Nursery in Wanneroo. It became available to the public in 2005, and has been registered successfully under Plant Breeders' Rights.[45]

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Wrigley (1991): 61–62.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Nelson (1995): 331.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 George, Alex (1984). An introduction to the Proteaceae of Western Australia. Kenthurst, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-86417-005-X.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hopper, Stephen D. (1980). "Bird and Mammal Pollen Vectors in Banksia Communities at Cheyne Beach, Western Australia". Australian Journal of Botany 28 (1): 61–75. doi:10.1071/BT9800061.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Nelson (1978): 389.

- ↑ Nelson (1975b): 139–144.

- ↑ Nelson (1975b) 1:24

- ↑ Duyker, Edward (2003). Citizen Labillardière: A naturalist's life in revolution and exploration. Carlton, Victoria: Miegunyah Press. pp. 133–34. ISBN 0-522-85160-6.

- ↑ "Adenanthos cuneatus Labill.". Robert Brown's Australian Botanical Specimens, 1801–1805 at the BM. Perth: FloraBase, Western Australian Herbarium, Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ↑ Nelson (1975a): 332.

- ↑ Nelson, E. Charles (1976). "Antoine Guichenot and Adenanthos (Proteaceae) specimens collected during Baudin's Australian Expedition, 1801–1803". Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History 8 (1): 1–10. doi:10.3366/jsbnh.1976.8.PART_1.1. ISSN 0260-9541.

- ↑ Leschenault de la Tour, Jean Baptiste (1816). "Notice sur la Végétation de la Nouvelle-Hollande et da la terre de Diémen". Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes (in French) 2. p. 366. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ↑ Nelson (1975b) 2: A126.

- ↑ Nelson (1978): 320.

- ↑ Nelson (1978): 318, 320.

- ↑ Knight, Joseph; [Salisbury, Richard] (1809). On the Cultivation of the Plants Belonging to the Natural Order of Proteeae. London, United Kingdom: W. Savage. p. 96.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Nelson (1978): 387.

- ↑ "Adenanthos flabellifolius Knight [ nom. illeg. ]". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

- ↑ Willdenow, Carl Ludwig (1825). Sprengel, Curt Polycarp Joachim, ed. Systema vegetabilium (in Latin) (16th ed.). Göttingen: Sumtibus Librariae Dieterichianae. p. 472.

- ↑ "Adenanthos crenatus Willd.". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

- ↑ Bentham, George (1870). "Adenanthos". Flora Australiensis 5. London: L. Reeve & Co. pp. 350–56.

- ↑ Nelson (1975b) 1: 123, 124.

- ↑ Nelson (1978): 320, 321.

- ↑ "Adenanthos cunninghamii (Albany Woollybush)" (PDF). Advice to the Minister for the Environment and Heritage from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) on Amendments to the list of Threatened Species under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ Cochrane, Anne; Barrett, S.; Byrne, M. (2004). "A rare hybrid beauty — Albany Woollybush". Landscope (Perth: Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM), Government of Western Australia) 19 (3): 7–8. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ Nelson (1978): 391.

- ↑ Nelson (1978): 392.

- ↑ Nelson, Ernest Charles (2005). "The koala plant and related monickers" (PDF). Australian Systematic Botany Society Newsletter (125): 2–3. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ "Adenanthos cuneatus". FloraBase. Department of Environment and Conservation, Government of Western Australia.

- ↑ Nelson (1975b): 299.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Nelson (1978): 388.

- ↑ Nelson (1975b): 262, 268.

- ↑ Nelson (1975b): 311.

- ↑ Nelson (1975b): 252.

- ↑ Nelson (1975b): 254.

- ↑ Nelson (1975b): 261.

- ↑ "Specimen Report". Museum Victoria website: Bioinformatics. Melbourne, Victoria: Museum Victoria. 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ↑ Weins, Delbert; Renfree, Marilyn; Wooller, Ronald D. (1979). "Pollen loads of Honey possums (Tarsipes spencerae) and non-flying mammal pollination in South-western Australia". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 66: 830–38. doi:10.2307/2398921. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ↑ Wooller, Ronald D.; Richardson, K. C.; Collins, B.G. (1993). "The relationship between nectar supply and the rate of capture of a nectar-dependent small marsupial Tarsipes rostratus". Journal of Zoology (London) 229: 651–58. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1993.tb02662.x.

- ↑ Sargent, O. H. (1928). "Reactions between birds and plants". Emu 27: 185–92. doi:10.1071/MU927185.

- ↑ "Part 2, Appendix 4: The responses of native Australian plant species to Phytophthora cinnamomi" (PDF). Management of Phytophthora cinnamomi for Biodiversity Conservation in Australia. Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government. 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ↑ Bishop, C.L.; Wardell-Johnson, G.W.; Williams, M.R. (2010). "Community-level changes in Banksia woodland following plant pathogen invasion in the Southwest Australian Floristic Region". Journal of Vegetation Science 21 (5): 888–98. doi:10.1111/j.1654-1103.2010.01194.x.

- ↑ Barrett, Sarah R.; Shearer, Bryan L.; Hardy, G.E.S. (2004). "Phytotoxicity in relation to in planta concentration of the fungicide phosphite in nine Western Australian native species". Australasian Plant Pathology 33 (4): 521–28. doi:10.1071/AP04055.

- ↑ Shearer, Bryan L.; Crane, C.E.; Fairman, Richard G.; Grant, M.J. (1998). "Susceptibility of Plant Species in Coastal Dune Vegetation of South-western Australia to Killing by Armillaria luteobubalina". Australian Journal of Botany 46 (2): 321–34. doi:10.1071/BT97012.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Nelson, Ernest Charles (2006). "Adenanthos Labill. - A Plantsman's Retrospect and Prospect". Australian Plants 23 (186): 199–214.

- ↑ Lullfitz, George. Grow the West's Best Native Plants. Perth: Periodicals Division, West Australian Newspapers. p. 39.

References

- Nelson, Ernest Charles (1975a). "The collectors and type locations of some of Labillardière's "terra van-Leuwin" (Western Australia) specimens". Taxon (IAPT) 24 (2/3): 319–36. doi:10.2307/1218341. JSTOR 1218341.

- Nelson, Ernest Charles (1975b). Taxonomy and Ecology of Adenanthos in Southern Australia (PhD thesis). Australian National University.

- Nelson, Ernest Charles (1978). "A taxonomic revision of the genus Adenanthos Proteaceae". Brunonia 1: 303–406. doi:10.1071/BRU9780303.

- Nelson, Ernest Charles (1995). "Adenanthos". In McCarthy, Patrick (ed.). Flora of Australia 16. Collingwood, Victoria, Australia: CSIRO Publishing / Australian Biological Resources Study. pp. 314–42. ISBN 0-643-05692-0.

- Wrigley, John; Fagg, Murray (1991). Banksias, Waratahs and Grevilleas. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-17277-3.

External links

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Adenanthos cuneatus |

Media related to Adenanthos cuneatus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Adenanthos cuneatus at Wikimedia Commons- "Adenanthos cuneatus". FloraBase. Department of Environment and Conservation, Government of Western Australia.

- "Adenanthos cuneatus Labill". Flora of Australia Online. Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government.

- "Adenanthos cuneatus Labill.". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.