Action of 18 August 1798

| Action of 18 August 1798 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

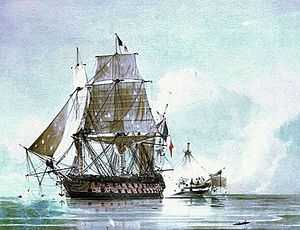

Action between H.M.S. Leander and the French National Ship Le Genereux, 18 August 1798, C. H. Seaforth | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Commodor Louis-Jean-Nicolas Lejoille[1] | Captain Thomas Thompson | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Ship of the line Généreux | Fourth rate HMS Leander | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~ 100 killed, 188 wounded | 35 killed, 57 wounded, Leander captured | ||||||

The Action of 18 August 1798 was a minor naval engagement of the French Revolutionary Wars, fought between the British fourth rate ship HMS Leander and the French ship of the line Généreux. Both ships had been engaged at the Battle of the Nile three weeks earlier, in which a British fleet under Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson had destroyed a French fleet at Aboukir Bay on the Mediterranean coast of Egypt. Généreux was one of only four French ships to survive the battle, while Leander had been detached from the British fleet by Nelson on 6 August. On board, Captain Edward Berry sailed as a passenger, charged with carrying despatches to the squadron under Earl St Vincent off Cadiz. On 18 August, while passing the western shore of Crete, Leander was intercepted and attacked by Généreux, which had separated from the rest of the French survivors the day before.

Captain Thomas Thompson on Leander initially tried to escape the much larger French ship, but it rapidly became clear that Généreux was faster than his vessel. At 09:00 the ships exchanged broadsides, the engagement continuing until 10:30 when Captain Louis-Jean-Nicolas Lejoille made an unsuccessful attempt to board Leander, suffering heavy casualties in the attempt. For another five hours the battle continued, Thompson successfully raking Généreux at one stage but ultimately being outfought and outmanoeuvered by the larger warship. Eventually the wounded Thompson surrendered his dismasted ship by ordering his men to wave a French tricolour on a pike. As French sailors took possession of the British ship, Lejoille encouraged systematic looting of the sailors' personal possessions, even confiscating the surgeon's tools in the middle of an operation. Against the established conventions of warfare, he forced the captured crew to assist in bringing Leander safely into Corfu, and denied them food and medical treatment unless they co-operated with their captors.

Lejoille's published account of the action greatly exaggerated the scale of his success, and although he was highly praised in the French press he was castigated in Britain for his conduct. Thompson, Berry and most of the British officers were exchanged and acquitted at court martial and the captains were knighted for their services, while Leander and many of the crew were recaptured in March 1799 by a Russian squadron that seized Corfu, and returned to British control by order of Tsar Paul. Généreux survived another year in the Mediterranean, but was eventually captured off Malta in 1800 by a British squadron under Lord Nelson.

Background

On 1 August 1798 a British fleet of 13 ships of the line and one fourth rate ship under Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson discovered a French fleet of 13 ships of the line and four frigates at anchor in Aboukir Bay on the Mediterranean coast of Egypt.[2] Nelson had been in pursuit of the French for three months, crossing the Mediterranean three times in his efforts to locate the fleet and a convoy under its protection which carried the French army commanded by Napoleon Bonaparte intended for the invasion of Egypt. The convoy successfully eluded Nelson and the army landed at Alexandria on 31 June, capturing the city and advancing inland. The fleet was too large to anchor in Alexandria harbour and instead Bonaparte ordered its commander, Vice-Admiral François-Paul Brueys D'Aigalliers to take up station in Aboukir Bay.[3]

On discovering the French Nelson attacked immediately, ordering his ships to advance on the French line and engage, beginning the Battle of the Nile. As he closed with the French line, Captain Thomas Foley on the lead ship HMS Goliath realised that there was a gap at the head of the French line wide enough to allow his ship passage. Pushing through the gap, Foley attacked the French van from the landward side, followed by four ships, while Nelson engaged the van from the seaward side with three more.[4] The remainder of the fleet attacked the French centre, except for HMS Culloden which grounded on a shoal and became stuck. The smaller ships in the squadron, the fourth rate HMS Leander and the sloop HMS Mutine, attempted to assist Culloden, but it was soon realised that the ship was immobile.[5] Determined to participate in the battle, Captain Thomas Thompson of Leander abandoned the stranded Culloden and joined the second wave of attack against the French centre, focusing fire on the bow of the 120-gun French first rate Orient.[6] Within an hour, Orient caught fire under the combined attack of three ships and later exploded, effectively concluding the engagement in Nelson's favour.[7] During the next two days, the lightly damaged Leander was employed in forcing the surrender of several grounded French vessels, and by the afternoon of 3 August Nelson was in complete control of Aboukir Bay. Only four French ships, two ships of the line and two frigates, escaped, sailing north out of the bay on the afternoon of 2 August under the command of Rear-Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve.[8]

Having won the battle, Nelson needed to send despatches to his commander, Vice-Admiral Earl St. Vincent reporting on the destruction of the French Mediterranean fleet. These messages were entrusted to Captain Edward Berry, who had served as Nelson's flag captain on HMS Vanguard during the battle.[9] Thompson was ordered to escort Berry to St. Vincent, believed to be with the blockade squadron off Cadiz, in Leander. Although Leander had not suffered serious damage in the battle, Thompson had manning problems: casualties from the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife in July 1797 had never been replaced, 14 men had been wounded in the battle at Aboukir Bay and two officers and fifty men had been detached to man the captured French prizes. This left Thompson with just 282 men on board Leander.[10] Following Nelson's orders, Thompson sailed on 5 August.[11]

Battle

After fleeing Aboukir Bay, Admiral Villeneuve had been delayed in the Eastern Mediterranean by northeasterly winds, and on 17 August he decided to split his forces, sailing for Malta with his flagship Guillaume Tell and the two frigates while Captain Louis-Jean-Nicolas Lejoille on Généreux was ordered to Corfu. Before they departed, a number of men were transferred to Généreux, which was already carrying survivors from Timoléon, one of the ships destroyed in Aboukir Bay, giving Généreux a crew of 936 men.[10] As Généreux rounded the island of Goza off the western tip of Crete (then known as Candia) on the following morning, his lookouts reported a sail to the northwest. This vessel was Leander. Learning of the strange ship to the southeast, Captain Thompson deduced that it must be one of Villeneuve's ships and immediately ordered all sails set in an effort to avoid an unequal combat: Généreux carried 30 more guns than Leander and was more strongly built,[12] carrying a broadside of over 1,000 lbs to Leander's 432 lbs.[13]

Assisted by a strong breeze behind his ship that did not carry to Thompson's vessel,[14] Lejoille rapidly gained on the fourth rate, hoisting Neapolitan and then Ottoman flags in an unsuccessful attempt to confuse Thompson into approaching his ship.[13] By 09:00 it was inevitable that Généreux would catch Leander and Thompson responded by shortening sail and turning northwards to aim his broadside at the French ship. Within minutes Généreux had fired a shot across Leander's bows and Thompson responded to the threat by ordering a full broadside against Généreux.[15] Lejoille replied with his own broadside, and the two ships continued firing as they sailed to the east, Généreux gradually closing the range with Leander. The smaller British vessel took the worst of the damage and at 10:30 the combatants were so close that Lejoille decided to attempt to board the British ship, Thompson unable to manoeuvre the battered Leander out of the way.[16] Généreux's bow collided with the bow of Leander and the French ship swung alongside, Lejoille preparing his men to board. Thompson was prepared for this manoeuvre and mustered his Royal Marines and teams of sailors armed with muskets along the rail of the quarterdeck and poop deck.[12] The volleys of musket fire were sufficient to kill any Frenchman who attempted to board the British ship and the tangled ships turned southwards together, their main batteries continuing to exchange broadsides at extreme close range. Gradually the strengthening breeze dragged Généreux free of Leander, the French ship faster as more of its sails and rigging were intact.[15]

As Généreux pulled away to the west, Thompson, who had already been wounded several times, succeeded in turning his battered ship so that his broadside was directed at the stern of Généreux. Despite the collapsed wreckage of the mizzenmast and fore topmast, his gunnery teams managed to cut away enough of the obstruction to fire a raking broadside at the French vessel. Although Leander had inflicted severe damage, the size and power of the French ship was beginning to tell, and Lejoille was able to turn Généreux southwards again.[17] The ships continued exchanging broadsides until 15:30, by which time Leander's crew had run out of regular shot and were firing scrap metal at the French ship.[13] Eventually Lejoille succeeded in bringing Généreux across Leander's bow and hailed the British ship, asking if they had surrendered.[15] Unable to continue fighting due to the wreckage that lay across the forward guns, Thompson ordered a French flag raised on a pike, which was sufficient for Lejoille to cease firing.[17]

The French were initially unable to take possession of the fourth rate as every single one of the boats on board had been smashed by British shot. In the end, a French midshipman and a boatswain dived into the sea and swam to the British ship to take the formal surrender.[14] Leander had lost a third of the crew: 35 men killed and 57 wounded, the latter including Thompson three times and Berry, who had a piece of human skull lodged in his arm.[18] The ship had been completely dismasted except the stubs of the fore and main masts and the bowsprit, and was leaking badly from dozens of shot holes.[19] Généreux had also been damaged, losing the mizzen topmast and almost losing the foremast as well. Losses on the crowded decks had been far more severe than on Leander, with casualties estimated at 100 killed and 188 wounded, again approximately a third of the total.[10]

Aftermath

The two French sailors that reached Leander immediately began a systematic pillaging of the British officers' personal effects.[20] Rather than tossing the men into the sea, as historian William James suggests they should have done, Thompson instead ordered one of the British boats to be repaired and launched to transport him to the French ship and bring back Captain Lejoille in the belief that he would end the looting.[21] However when the French captain arrived he immediately joined his officers, commandeering all but two of Captain Thompson's shirts and the wounded officer's cot. When Captain Berry complained that a pair of ornamental pistols had been stolen from him, Lejoille summoned the thief to the quarterdeck and took them for himself.[22] The sailors who accompanied Lejoille were equally voracious: among the many things taken were the ship surgeon Mr Mulberry's operating tools, stolen in the middle of an operation. Without the correct equipment, the surgeon could not assist the many wounded, including Captain Thompson, who had a musket ball still embedded deeply in his arm.[23] When Captain Berry complained, Lejoille replied "J'en suis fâché, mais le fait est, que les Français sont bons au pillage" ("I'm sorry, but the fact is, that the French are good at plunder").[22]

Dividing the captured British sailors, Lejoille transferred half to Généreux and left half on Leander with a French prize crew under Louis Gabriel Deniéport. In direct contravention of the established conventions of war, both sets of prisoners were immediately ordered to effect repairs to the vessels. Only once both ships were ready for the journey to Corfu were the prisoners given bread and water, although the wounded were still denied medical attention.[24] For ten days after the engagement the battered ships sailed northwards against the wind, Généreux forced to attach a tow to Leander to avoid leaving the prize behind.[23] On 28 August, a sail appeared to the south. Panic broke out on Généreux, and Lejoille ordered the prisoners confined below and for preparations to be made to abandon Leander and make all speed for Corfu. The new arrival was in fact the 16-gun British sloop HMS Mutine under Lieutenant Thomas Bladen Capel, carrying the second copies of Nelson's despatches to Britain. Capel sighted the ships to the north, but assumed that they were Généreux and Guillaume Tell and so passed by displaying French colours. Lejoille was not fooled by the disguise but did not pursue the small vessel, continuing his passage to Corfu once Mutine had sailed out of sight.[24]

At Corfu the prisoners were confined but the wounded were still not provided with treatment: Thompson was only able to have the musket ball removed from his arm when Mulberry was smuggled aboard Généreux in Corfu harbour without Lejoille's knowledge or permission.[23] The British officers were eventually paroled and returned to Britain, although the carpenter Thomas Jarrat was detained because he refused to supply Lejoille with the specifications of Leander's masts.[25] Most of the ship's regular seamen were held prisoner at Corfu. They were subsequently encouraged to join the French Navy, Lejoille attempting to enlist them on Généreux when a Russian squadron blockaded the port. Lejoille's demands were met with a response from a maintopman named George Bannister, who called out "No, you damned French rascal, give us back our little ship, and we'll fight you again until we sink".[24] Généreux subsequently escaped from Corfu and anchored off Brindisi, where Lejoille was killed by artillery fire from the Neapolitan castle overlooking the town.[26] The ship was captured in a battle in February 1800 by a squadron under Nelson, off Malta.[27] Leander was captured by a Russian force that seized Corfu in March 1799 and was returned to the Royal Navy by Tsar Paul, along with the sailors held on the island.[20]

The account of the battle Captain Lejoille sent to France was inaccurate in a number of important features, describing Leander as a 74-gun ship and claiming that his men actually boarded the British ship, only to subsequently retreat.[28] Coming so soon after their disaster at the Battle of the Nile and encouraged by Lejoille's highly inaccurate reports, French newspapers exaggerated the scale of the victory, Le Moniteur Universel publishing several imaginative accounts in the months after the battle.[29] Despite the defeat the action was celebrated in Britain, Thompson and Berry praised for their defiance against a much larger vessel rather than criticised for losing their ship.[30] Lejoille's conduct in the treatment of his prisoners was derided in the popular press and on 17 December 1798 Thompson, Berry and the ship's officers were brought before a court martial on HMS America at Sheerness for the loss of their ship and honourably acquitted, the court announcing that;

"The Court having heard the evidence brought forward in support of Captain Thompson's narrative of the capture of Leander, and having very maturely and deliberately considered the whole, is of opinion, that the gallant and almost unprecedented defence of Captain Thompson, of his majesty's late ship Leander, against so superior force as that of the Généreux, is deserving of every praise his Country and this Court can give; and that his conduct, with that of the officers and men under his command, reflects not only the highest honour upon himself and them, but on their Country at large, and the court does therefore most honourably acquit Captain Thompson, his officers, and ship's company; and he and they are most honourably acquitted accordingly."—Court martial verdict, quoted in The Naval Chronicle 1793–1798, Volume 1, Edited by Nicholas Tracy, [28]

Thompson and Berry were subsequently voted the thanks of Parliament and in December 1798 Berry was made a Knight Bachelor, given the Freedom of the City of London and a chest worth 100 guineas. He was subsequently made commander of the new 80-gun HMS Foudroyant in early 1799, and returned to the Mediterranean to operate as Nelson's flag captain again during the Siege of Malta.[31] Thompson was knighted in January 1799 and given a pension of £200 per annum, returning to service that spring as captain of HMS Bellona attached to the Channel Fleet under Lord Bridport.[32]

Captain Peune, who had commanded the bomb-ship chartered to ferry Thompson and his staff from Corfu to Trieste, wrote a letter to answer the charges of pillage. He stated that the 30-men French prize crew was unarmed, having had to swim to Leander because all the boats on Généreux and Leander had been destroyed in the battle, and that the 200 men still able on Leander would have stopped them from plundering their effects; that neither the captain not the surgeon of the ship had complained at Corfu nor at Trieste; and that on his ship, he had seen Thompson with three trunks of personal effects, and the other members of his staff with their own as well.[33] In his Batailles navales de la France, Troude accuses William James of further "augmenting" the accusations originally published in the Gazette de Vienne.[34] The allegations are not present in Thompson's account in The Gentleman's Magazine.[35]

Notes

- ↑ Moulin, p. 160

- ↑ Clowes, p. 355

- ↑ James, p. 159

- ↑ Adkins, p. 24

- ↑ Clowes, p. 363

- ↑ Clowes, p. 364

- ↑ James, p. 171

- ↑ Gardiner, p. 38

- ↑ Tracy, p. 277

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 James, p. 233

- ↑ Clowes, p. 513

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Tracy, p. 278

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Gardiner, p. 42

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Woodman, p. 113

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Clowes, p. 514

- ↑ James, p. 231

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 James, p. 232

- ↑ Clowes, p. 515

- ↑ Tracy, p. 279

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Gardiner, p. 43

- ↑ James, p. 234

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Tracy, p. 280

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 James, p. 235

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Clowes, p. 516

- ↑ James, p. 236

- ↑ James, p. 271

- ↑ Clowes, p. 419

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Tracy, p. 281

- ↑ James, p. 237

- ↑ James, p. 238

- ↑ Laughton, J. K.. "Berry, Sir Edward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (subscription or UK public library membership required). Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- ↑ Laughton, J. K.. "Thompson, Sir Thomas Boulden". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (subscription or UK public library membership required). Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- ↑ Troude, p.143

- ↑ Troude, p.144

- ↑ The Gentleman's Magazine, Volume 68, Part 2

Bibliography

- Adkins, Roy & Lesley (2006). The War for All the Oceans. Abacus. ISBN 0-349-11916-3.

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed (2001). Nelson Against Napoleon. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-86176-026-4.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 2, 1797–1799. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-906-9.

- Moulin, Henri (1883). Les marins de la République: le Vengeur et les droits de l'homme, la Loire et la Bayonnaise, le treize prairial, Aboukir et Trafalgar [The Mariners of the Republic ...] (in French). Paris: Charavay. OCLC 8094027.

- Tracy, Nicholas (editor) (1998). The Naval Chronicle, Volume 1, 1793–1798; "Leander's Two Battles". Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-091-4.

- Woodman, Richard (2001). The Sea Warriors. Constable Publishers. ISBN 1-84119-183-3.

- Troude, Onésime-Joachim (1867). Batailles navales de la France 3. Challamel ainé. pp. 140–144.