Acne vulgaris

| Acne vulgaris | |

|---|---|

Acne in a 14-year-old male during puberty | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | L70.0 |

| ICD-9 | 706.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 10765 |

| MedlinePlus | 000873 |

| eMedicine | derm/2 |

| Patient UK | Acne vulgaris |

| MeSH | D000152 |

Acne vulgaris (or simply acne) is a long-term skin condition characterized by areas of blackheads, whiteheads, pimples, greasy skin, and possibly scarring.[1][2] The resulting appearance may lead to anxiety, reduced self-esteem, and in extreme cases, depression or thoughts of suicide.[3][4]

Genetics is estimated to be the cause of 80% of cases.[2] The role of diet as a cause is unclear.[2] Neither cleanliness nor sunlight appear to be involved.[2] However, cigarette smoking does increase the risk of developing acne and worsens its severity.[5] Acne mostly affects skin with a greater number of oil glands including the face, upper part of the chest, and back.[6] During puberty in both sexes, acne is often brought on by an increase in androgens such as testosterone.[7] The bacteria Propionibacterium acnes is also often involved.[7]

Many treatment options are available to improve the appearance of acne including lifestyle changes, procedures, and medications. Eating fewer simple carbohydrates like sugar may help.[8] Topical benzoyl peroxide, salicylic acid, and azelaic acid are commonly used treatments.[9] Antibiotics and retinoids are available topically and by mouth to treat acne.[9] However, resistance to antibiotics may develop.[10] A number of birth control pills may be useful in women.[9] Oral isotretinoin is usually reserved for severe acne due to greater potential side effects.[9] Early and aggressive treatment is advocated by some to lessen the overall long-term impact to individuals.[4]

Acne occurs most commonly during adolescence, affecting an estimated 80–90% of teenagers in the Western world.[11][12][13] Lower rates are reported in some rural societies.[13][14] In 2010, acne was estimated to affect 650 million people globally making it the 8th most common disease worldwide.[15] People may also be affected before and after puberty.[16] Though it becomes less common in adulthood than in adolescence, nearly half of people in their twenties and thirties continue to have acne.[2] About 4% continue to have difficulties into their forties.[2]

Classification

Acne is commonly classified by severity as mild, moderate, or severe. This type of categorization can be an important factor in determining the appropriate treatment regimen.[12] Mild acne is classically defined as open (blackheads) and closed comedones (whiteheads) limited to the face with occasional inflammatory lesions.[12] Acne may be considered to be of moderate severity when a higher number of inflammatory papules and pustules occur on the face compared to mild cases of acne and acne lesions also occur on the trunk of the body.[12] Lastly, severe acne is said to occur when nodules and cysts are the characteristic facial lesions and involvement of the trunk is extensive.[12]

Signs and symptoms

Typical features of acne include seborrhea (increased oil secretion), microcomedones, comedones, papules, pustules, nodules (large papules), and possibly scarring.[1][17] The appearance of acne varies with skin color. It may result in psychological and social problems.[12]

Some of the large nodules were previously called cysts and the term nodulocystic has been used to describe severe cases of inflammatory acne.[18]

Scars

Acne scars are the result of inflammation within the dermal layer of skin brought on by acne and are estimated to affect 95% of people with acne vulgaris.[19] The scar is created by an abnormal form of healing following this dermal inflammation.[19] Scarring is most likely to occur with severe nodulocystic acne, but may occur with any form of acne vulgaris.[19] Acne scars are classified based on whether the abnormal healing response following dermal inflammation leads to excess collagen deposition or collagen loss at the site of the acne lesion.[19]

Atrophic acne scars are the most common type of acne scar and have lost collagen from this healing response.[19] Atrophic scars may be further classified as ice-pick scars, boxcar scars, and rolling scars.[19] Ice pick scars are typically described as narrow (less than 2 mm across), deep scars that extend into the dermis.[19] Rolling scars are wider than ice pick scars (4–5 mm across) and have a wave-like pattern of depth in the skin.[19] Boxcar scars are round or ovoid indented scars with sharp borders and vary in size from 1.5–4 mm across.[19]

Hypertrophic scars are less common and are characterized by increased collagen content after the abnormal healing response.[19] They are described as firm and raised from the skin.[19][20] Hypertrophic scars remain within the original margins of the wound whereas keloid scars can form scar tissue outside of these borders.[19] Keloid scars from acne usually occur in men and on the trunk of the body rather than the face.[19]

Pigmentation

Postinflammatory hyper pigmentation (PIH) is usually the result of nodular or cystic acne (the painful 'bumps' lying under the skin). They often leave behind an inflamed red mark after the original acne lesion has resolved. PIH occurs more often in people with darker skin color.[21] Pigmented scar is a common but misleading term, as it suggests the color change is permanent. Often, PIH can be avoided by avoiding aggravation of the nodule or cyst. These scars can fade with time. However, untreated scars can last for months, years, or even be permanent if deeper layers of skin are affected.[22] Daily use of SPF 15 or higher sunscreen can minimize pigmentation associated with acne.[22]

-

A severe case of cystic acne

-

Cystic acne on the back.

-

Acne vulgaris types: A: Facial cystic acne, B: Subsiding tropical acne of trunk, C: Extensive chest and shoulder acne.

Cause

Genetic

The predisposition for specific individuals to acne is likely explained in part by a genetic component, which has been supported by twin studies as well as studies that have looked at rates of acne among first degree relatives.[23] The genetics of acne susceptibility is likely polygenic, as the disease does not follow classic Mendelian inheritance pattern. There are multiple candidates for genes which are possibly related to acne, including polymorphisms in TNF-alpha, IL-1 alpha, and CYP1A1 among others.[11]

Hormonal

Hormonal activity, such as menstrual cycles and puberty, may contribute to the formation of acne. During puberty, an increase in sex hormones called androgens cause the follicular glands to grow larger and make more sebum.[6][24] A similar increase in androgens occurs during pregnancy, also leading to increased sebum production.[25]

Several hormones have been linked to acne including the androgens testosterone, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), as well as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I) and growth hormone.[26] Use of anabolic steroids may have a similar effect.[27]

Acne that develops between the ages of 21 and 25 is uncommon.[28] True acne vulgaris in adult women may be due to pregnancy or polycystic ovary syndrome.[29]

Infectious

Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) is the anaerobic bacterium species that is widely suspected to contribute to the development of acne, but its exact role in this process is not entirely clear.[23][30] There are specific sub-strains of P. acnes associated with normal skin and others with moderate or severe inflammatory acne.[31] It is unclear whether these undesirable strains evolve on-site or are acquired, or possibly both depending on the person. These strains either have the capability of changing, perpetuating, or adapting to, the abnormal cycle of inflammation, oil production, and inadequate sloughing of acne pores. One particularly virulent strain, has been circulating in Europe for at least 87 years.[32] Infection with the parasitic mite Demodex is associated with the development of acne.[17][33] However, it is unclear if eradication of these mites improves acne.[33]

Lifestyle

Cigarette smoking is known to increase the risk of developing acne.[5] Additionally, acne severity worsens as the number of cigarettes a person smokes increases.[5] The relationship between diet and acne is unclear as there is no high-quality evidence.[34] However, a high glycemic load diet is associated with worsening acne.[8][35] There is weak evidence of a positive association between the consumption of milk and a greater rate and severity of acne.[33][36][37][38] Other associations such as chocolate and salt are not supported by the evidence.[36] Chocolate does contain a varying amount of sugar that can lead to a high glycemic load and it can be made with or without milk. There may be a relationship between acne and insulin metabolism and one trial found a relationship between acne and obesity.[39] Vitamin B12 may trigger acneiform eruptions, or exacerbate existing acne, when taken in doses exceeding the recommended daily intake.[40]

Psychological

While the connection between acne and stress has been debated, research indicates that increased acne severity is associated with high stress levels.[41][42]

Pathophysiology

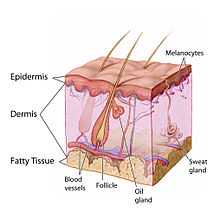

Acne develops as a result of blockages in the skin's follicles. These blockages are thoughts to occur as a result of the following four abnormal processes: a higher than normal amount of sebum production (influenced by androgens); excessive keratin deposition leading to comedone formation; colonization of the follicle by Propionibacterium acnes bacteria; and the local release of pro-inflammatory chemicals in the skin.[31]

The earliest pathologic changes are the excessive deposition of the protein keratin and oily sebum in the hair follicle resulting in the formation of a plug (a microcomedo).[6] During adrenarche, a higher level of the androgen (DHEA-S) results in the enlargement of the sebaceous glands and increases sebum production. A microcomedo may enlarge to form an open comedo (blackhead) or closed comedo. The dark color of a blackhead occurs due to oxidation of the skin pigment melanin.[12]

Comedones result from the clogging of sebaceous glands with sebum, a naturally occurring oil, and dead skin cells.[6] In these conditions, the naturally occurring largely commensal bacterium Propionibacterium acnes can cause inflammation within and around the follicle, leading to inflammatory lesions (papules, infected pustules, or nodules) in the dermis around the microcomedo or comedone, which results in redness and may result in scarring or hyperpigmentation.[6][43][44] Severe acne is inflammatory, but acne can also be noninflammatory.[28]

Diagnosis

There are multiple scales for grading the severity of acne vulgaris,[45] three of these being:

- Leeds acne grading technique: Counts and categorizes lesions into inflammatory and non-inflammatory (ranges from 0–10.0).

- Cook's acne grading scale: Uses photographs to grade severity from 0 to 8 (0 being the least severe and 8 being the most severe).

- Pillsbury scale: Simply classifies the severity of the acne from 1 (least severe) to 4 (most severe).

Differential diagnosis

Similar conditions include rosacea, folliculitis, keratosis pilaris, perioral dermatitis, and angiofibromas among others.[12] Age is one factor that may help a physician distinguish between these disorders. Skin disorders such as perioral dermatitis and keratosis pilaris can mimic acne but tend to occur more frequently in childhood whereas rosacea tends to occur more frequently in older adults.[12] Facial redness triggered by heat or the consumption of alcohol or spicy food is suggestive of rosacea.[46] The presence of comedones can also help health professionals differentiate acne from skin disorders that are similar in appearance.[9]

Management

Many different treatments exist for acne including benzoyl peroxide, antibiotics, retinoids, antiseborrheic medications, anti-androgen medications, hormonal treatments, salicylic acid, alpha hydroxy acid, azelaic acid, nicotinamide, and keratolytic soaps.[47] They are believed to work in at least four different ways, including the following: normalizing skin cell shedding and sebum production into the pore to prevent blockage, killing P. acnes, anti-inflammatory effects, and hormonal manipulation.[6]

Commonly used medical treatments include topical therapies such as retinoids, antibiotics, and benzoyl peroxide and systemic therapies including oral retinoids, antibiotics, and hormonal agents.[12][48] Procedures such as light therapy and laser therapy are not considered to be first-line treatments and typically have an adjunctive role due to their high cost and limited evidence of efficacy.[48]

Medications

Benzoyl peroxide

Benzoyl peroxide is a first-line treatment for mild and moderate acne due to its effectiveness and mild side-effects (mainly irritant dermatitis). It works against P. acnes, helps prevent formation of comedones, and has anti-inflammatory properties.[6] Benzoyl peroxide normally causes dryness of the skin, slight redness, and occasional peeling when side effects occur.[49] This topical does increase sensitivity to the sun as indicated on the package, so sunscreen use is often advised during the treatment to prevent sunburn. Benzoyl peroxide has been found to be nearly as effective as antibiotics with all concentrations being equally effective.[49] Unlike antibiotics, benzoyl peroxide does not appear to generate bacterial resistance.[49] Benzoyl peroxide may be paired with a topical antibiotic or retinoid such as benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin and benzoyl peroxide/adapalene, respectively.[21]

Antibiotics

Topical antibiotics are frequently used for mild to moderate severe acne.[12] Oral antibiotics are indicated for moderate to severe cases of inflammatory acne and decrease acne due to their antimicrobial activity against P. acnes in conjunction with anti-inflammatory properties.[6][12][49] They are believed to work both by decreasing the number of bacterial and as an anti-inflammatory.[2] With increasing resistance of P. acnes worldwide, they are becoming less effective.[49] Commonly used antibiotics, either applied topically or taken orally, include erythromycin (category B), clindamycin (category B), metronidazole (category B), and tetracyclines such as doxycycline and minocycline.[25] Topical erythromycin and clindamycin are considered safe to use as acne treatment during pregnancy due to negligible systemic absorption.[25] Nadifloxacin and dapsone are other topical antibiotics that may be used to treat acne in pregnant women, but have received less extensive study.[25] It is recommended that oral antibiotics be stopped and topical retinoids be used once the disease has improved.[9]

Salicylic acid

Salicylic acid (category C)[25] is a topically applied beta-hydroxy acid that possesses bacteriostatic and keratolytic properties.[50][51] Additionally, salicylic acid opens obstructed skin pores and promotes shedding of epithelial skin cells.[50] However, salicylic acid is known to be less effective than retinoid therapy.[12] Hyperpigmentation of the skin has been observed in individuals with darker skin types who use salicylic acid.[6]

Azelaic acid

Azelaic acid has been shown to be effective for mild-to-moderate acne when applied topically at a 20% concentration.[43] Application twice daily for six months is necessary, and treatment is as effective as topical benzoyl peroxide 5%, isotretinoin 0.05%, and erythromycin 2%.[52] Azelaic acid is thought to be an effective acne treatment due to its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antikeratinizing properties.[43] Azelaic acid may cause skin irritation but is otherwise very safe.[53]

Hormones

In women, acne can be improved with the use of any combined oral contraceptive.[54] The combinations that contain third or fourth generation progestins such as desogestrel, norgestimate, or drospirenone may theoretically be more beneficial.[54] Antiandrogens such as cyproterone acetate and spironolactone have also been used successfully to treat acne.[25] Hormonal therapies should not be used to treat during pregnancy or lactation as they have been associated with certain birth defects such as hypospadias and feminization of the male fetus.[25]

Topical retinoids

Topical retinoids are medications that possess anti-inflammatory properties and work by normalizing the follicle cell life cycle.[6] They are a first-line acne treatment for people with dark colored skin and are known to lead to faster improvement of post inflammatory hyperpigmentation.[21] This class includes tretinoin (category C), adapalene (category C), and tazarotene (category X).[25] Like isotretinoin, they are related to vitamin A,[6] but are administered topically and generally have much milder side effects. They can, however, cause significant irritation of the skin. The retinoids appear to influence the cell life cycle in the follicle lining. This helps prevent the hyperkeratinization of these cells that can create a blockage. Retinol is a form of vitamin A that has similar, but milder effects and is used in many over-the-counter moisturizers and other topical products. Topical retinoids often cause an initial flare-up of acne and facial flushing.

Oral retinoids

Isotretinoin is very effective for severe acne as well as moderate acne refractory to other treatments.[12] Improvement is typically seen after one to two months of use. After a single course, about 80% of people report an improvement with more than 50% reporting complete remission.[12] About 20% of people require a second course.[12] A number of adverse effects may occur including: dry skin, nose bleeds, muscle pains, increased liver enzymes, and increased lipid levels in the blood.[12] If used during pregnancy, there is a high risk of abnormalities in the baby and thus women of child bearing age are required to use effective birth control.[12] There is no clear evidence that use of oral retinoids increases the risk of psychiatric side effects such as depression and suicidality.[12]

Spironolactone

The aldosterone antagonist spironolactone is an effective treatment for acne in adult women, but is not approved by the United States' Food and Drug Administration for this purpose.[21] Spironolactone is thought to be a useful acne treatment due to its ability to block the androgen receptor at higher doses.[21] It may be used with or without an oral contraceptive.[21]

Combination therapy

Combination therapy using medications of different classes together, each with a different mechanism of action, has been demonstrated to be a more efficacious approach to acne treatment than monotherapy.[25] Frequently used combinations include the following: antibiotic + benzoyl peroxide, antibiotic + topical retinoid, or topical retinoid + benzoyl peroxide.[25]

Procedures

Comedo extraction may temporarily help those with comedones that do not improve with standard treatment.[9] A procedure for immediate relief is the injection of corticosteroids into the inflamed acne comedone.[6] There is no evidence that microdermabrasion is effective.[9]

Light therapy is a method that involves delivering intense pulses of light to the area with acne sometimes following the application of a sensitizing substance (such as aminolevulinic acid).[55] This process is thought to kill bacteria and decrease the size and activity of the glands that produce sebum.[55] As of 2012, evidence for light therapy and lasers is insufficient to recommend routine use.[9] Light therapy is expensive, and while it appears to provide short-term benefit, there is a lack of long-term outcome data or data in those with severe acne.[6][56]

Dermabrasion is an effective therapeutic procedure for reducing the appearance of superficial atrophic scars of the boxcar and rolling varieties.[19] Ice pick scars do not respond well to treatment with dermabrasion due to their depth.[19] However, the procedure is painful and has many potential side effects such as skin sensitivity to sunlight, redness, and decreased pigmentation of the skin.[19] The procedure has fallen out of favor with the introduction of laser resurfacing.[19]

Laser resurfacing can be used to reduce the scars left behind by acne.[57] Ablative fractional photothermolysis laser resurfacing was found to be more effective for reducing acne scar appearance than non-ablative fractional photothermolysis, but was associated with higher rates of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (usually about 1-month duration), facial redness (usually for 3–14 days), and pain during the procedure.[58]

Chemical peels can also be used to reduce the appearance of acne scars.[19] Mild chemical peels include those using glycolic acid, lactic acid, salicylic acid, Jessner's solution, or a lower concentration (20%) of trichloroacetic acid. These peels only affect the epidermal layer of the skin and can be useful in the treatment of superficial acne scars as well as skin pigmentation changes from inflammatory acne.[19] Higher concentrations of trichloroacetic acid (30-40%) are considered to be medium strength peels and affect skin as deep as the papillary dermis.[19] Formulations of trichloroacetic acid concentrated to 50% or more are considered to be deep chemical peels.[19] Medium and deep strength chemical peels are more effective for deeper atrophic scars, but are more likely to cause side effects such as skin pigmentation changes, infection, or milia.[19]

Alternative medicine

Numerous natural products have been investigated for treating people with acne.[59][60] A topical application of tea tree oil has been suggested.[61] Evidence is insufficient to support their use.[62]

Prognosis

Acne usually improves around the age of 20 but may persist into adulthood.[47] Permanent physical scarring may occur.[12] There is good evidence to support the idea that acne has a negative psychological impact and worsens mood, lowers self-esteem, and is associated with a higher risk of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts.[33]

Epidemiology

Globally acne affects approximately 650 million people, or about 9.4% of the population, as of 2010.[63] It affects almost 90% of people in Western societies during their teenage years and may persist into adulthood.[12] Acne after the age of 25 affects 54% of women and 40% of men.[25] Acne vulgaris has a lifetime prevalence of 85%.[25] About 20% have moderate or severe cases.[23] It is slightly more common in females than males (9.8% versus 9.0%).[63] In those over 40 years old, 1% of males and 5% of females still have problems.[12]

Rates appear to be lower in rural societies.[14] While some find it affects people of all ethnic groups,[64] it may not occur in the non-Westernized people of Papua New Guinea and Paraguay.[23]

Acne affects 40 to 50 million people in the United States (16%) and approximately 3 to 5 million in Australia (23%).[65] In the United States, acne tends to be more severe in Caucasians than people of African descent.[6]

History

- Ancient Egypt, Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome: Sulfur was used to treat acne.[66]

- 1920s: Benzoyl peroxide was used as a medication to treat acne.[67]

- 1970s: Tretinoin (original Trade Name Retin A) was found to be an effective treatment for acne.[68] This preceded the development of oral isotretinoin (sold as Accutane and Roaccutane) in 1980.[69] Also, antibiotics such as minocycline are used as treatments for acne.

- 1980s: Accutane is introduced in the United States, and later found to be a teratogen, highly likely to cause birth defects if taken during pregnancy. In the United States, more than 2,000 women became pregnant while taking the drug between 1982 and 2003, with most pregnancies ending in abortion or miscarriage. About 160 babies with birth defects were born.[70][71]

Society and culture

Cost

The social and economic costs of treating acne vulgaris are substantial. In the United States, acne vulgaris is responsible for more than 5 million doctor visits and costs over $2.5 billion each year in direct costs.[5] Similarly, acne vulgaris is responsible for 3.5 million doctor visits each year in the United Kingdom.[12]

Stigma

Misperceptions about acne's causative and aggravating factors are common and those affected by acne are often blamed for their condition.[4] Such blame can worsen the affected person's sense of self-esteem.[4] Acne vulgaris and its resultant scars have been associated with significant social difficulties that can last into adulthood.[72]

Research

In 2007, the first genome sequencing of a P. acnes bacteriophage (PA6) was reported. The authors proposed applying this research toward development of bacteriophage therapy as an acne treatment in order to overcome the problems associated with long-term antibiotic therapy, such as bacterial resistance.[73]

A vaccine against inflammatory acne has been tested successfully in mice, but has not yet been proven to be effective in humans.[74] Other workers have voiced concerns related to creating a vaccine designed to neutralize a stable community of normal skin bacteria that is known to protect the skin from colonization by more harmful microorganisms.[75]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Adityan B, Kumari R, Thappa DM (May 2009). "Scoring systems in acne vulgaris". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology 75 (3): 323–6. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.51258. PMID 19439902.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Bhate, K; Williams, HC (March 2013). "Epidemiology of acne vulgaris.". The British journal of dermatology 168 (3): 474–85. doi:10.1111/bjd.12149. PMID 23210645.

- ↑ Barnes LE, Levender MM, Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR (April 2012). "Quality of life measures for acne patients". Dermatologic Clinics 30 (2): 293–300. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.11.001. PMID 22284143.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Goodman, G (July 2006). "Acne and acne scarring–the case for active and early intervention". Australian family physician 35 (7): 503–4. PMID 16820822.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Knutsen-Larson S, Dawson AL, Dunnick CA, Dellavalle RP (January 2012). "Acne vulgaris: pathogenesis, treatment, and needs assessment". Dermatologic Clinics 30 (1): 99–106. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.09.001. PMID 22117871.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 Benner N, Sammons D (September 2013). "Overview of the treatment of acne vulgaris". Osteopathic Family Physician 5 (5): 185–90. doi:10.1016/j.osfp.2013.03.003.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 James WD (April 2005). "Acne". New England Journal of Medicine 352 (14): 1463–72. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp033487. PMID 15814882.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Mahmood SN, Bowe WP (April 2014). "Diet and acne update: carbohydrates emerge as the main culprit". Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD 13 (4): 428–35. PMID 24719062.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 Titus S, Hodge J (October 2012). "Diagnosis and treatment of acne". American family physician 86 (8): 734–40. PMID 23062156.

- ↑ Beylot, C; Auffret, N; Poli, F; Claudel, JP; Leccia, MT; Del Giudice, P; Dreno, B (March 2014). "Propionibacterium acnes: an update on its role in the pathogenesis of acne.". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV 28 (3): 271–8. doi:10.1111/jdv.12224. PMID 23905540.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Taylor, Marisa; Gonzalez, Maria; Porter, Rebecca (May–June 2011). "Pathways to inflammation: acne pathophysiology". European Journal of Dermatology 21 (3): 323–33. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1357. PMID 21609898.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 12.9 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 12.17 12.18 12.19 12.20 12.21 12.22 Dawson AL, Dellavalle RP (May 2013). "Acne vulgaris". BMJ 346 (5): f2634. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2634. PMID 23657180.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Berlin, David J. Goldberg, Alexander L. Acne and Rosacea Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. London: Manson Pub. p. 8. ISBN 9781840766165.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Spencer EH, Ferdowsian, Barnard ND (April 2009). "Diet and acne: a review of the evidence.". International Journal of Dermatology 48 (4): 339–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04002.x. PMID 19335417.

- ↑ Hay, RJ; Johns, NE; Williams, HC; Bolliger, IW; Dellavalle, RP; Margolis, DJ; Marks, R; Naldi, L; Weinstock, MA; Wulf, SK; Michaud, C; J L Murray, C; Naghavi, M (October 2013). "The Global Burden of Skin Disease in 2010: An Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact of Skin Conditions". The Journal of investigative dermatology 134 (6): 1527–34. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.446. PMID 24166134.

- ↑ Admani S, Barrio VR (November 2013). "Evaluation and treatment of acne from infancy to preadolescence". Dermatologic therapy 26 (6): 462–6. doi:10.1111/dth.12108. PMID 24552409.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Zhao YE, Hu L, Wu LP, Ma JX (March 2012). "A meta-analysis of association between acne vulgaris and Demodex infestation". Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B 13 (3): 192–202. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1100285. PMC 3296070. PMID 22374611.

- ↑ Thiboutot, Diane M.; Strauss, John S. (2003). "Diseases of the sebaceous glands". In Burns, Tony; Breathnach, Stephen; Cox, Neil; Griffiths, Christopher. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 672–87. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 19.8 19.9 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 19.14 19.15 19.16 19.17 19.18 19.19 19.20 19.21 Levy, LL; Zeichner, JA (October 2012). "Management of acne scarring, part II: a comparative review of non-laser-based, minimally invasive approaches". Am J Clin Dermatol 13 (5): 331–40. doi:10.2165/11631410-000000000-00000. PMID 22849351.

- ↑ Sobanko, JF; Alster, TS (October 2012). "Management of acne scarring, part I: a comparative review of laser surgical approaches". Am J Clin Dermatol 13 (5): 319–30. doi:10.2165/11598910-000000000-00000. PMID 22612738.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Yin NC, McMichael AJ (February 2014). "Acne in patients with skin of color: practical management". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 15 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1007/s40257-013-0049-1. PMID 24190453.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Callender, VD; St Surin-Lord, S; Davis, EC; Maclin, M (April 2011). "Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: etiologic and therapeutic considerations". Am J Clin Dermatol 12 (2): 87–99. doi:10.2165/11536930-000000000-00000. PMID 21348540.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Bhate K, Williams HC (March 2013). "Epidemiology of acne vulgaris.". The British journal of dermatology 168 (3): 474–85. doi:10.1111/bjd.12149. PMID 23210645.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions: Acne". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Public Health and Science, Office on Women's Health. 16 July 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 25.6 25.7 25.8 25.9 25.10 25.11 Kong YL, Tey HL (June 2013). "Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation". Drugs 73 (8): 779–87. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0. PMID 23657872.

- ↑ Hoeger, Peter H.; Alan D. Irvine; Albert C. Yan (2011). Chapter 79 Acne Harper's Textbook of Pediatric Dermatology (3rd ed.). New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-44-434536-0.

- ↑ Melnik, Bodo; Jansen, Thomas; Grabbe, Stephan (2007). "Abuse of anabolic-androgenic steroids and bodybuilding acne: An underestimated health problem". JDDG 5 (2): 110–17. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06176.x. PMID 17274777.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Holzmann R, Shakery K (November 2013). "Postadolescent acne in females". Skin pharmacology and physiology 27 (Supplement 1): 3–8. doi:10.1159/000354887. PMID 24280643.

- ↑ Housman E, Reynolds RV (November 2014). "Polycystic ovary syndrome: A review for dermatologists: Part I. Diagnosis and manifestations". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 71 (5): 847. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.05.007. PMID 25437977.

- ↑ Bek-Thomsen, M.; Lomholt, H. B.; Kilian, M. (2008). "Acne is Not Associated with Yet-Uncultured Bacteria". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 46 (10): 3355–60. doi:10.1128/JCM.00799-08. PMC 2566126. PMID 18716234.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Simonart T (December 2013). "Immunotherapy for acne vulgaris: current status and future directions". American journal of clinical dermatology 14 (6): 429–35. doi:10.1007/s40257-013-0042-8. PMID 24019180.

- ↑ Lomholt, Hans B.; Kilian, Mogens (2010). Bereswill, Stefan, ed. "Population Genetic Analysis of Propionibacterium acnes Identifies a Subpopulation and Epidemic Clones Associated with Acne". PLoS ONE 5 (8): e12277. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012277. PMC 2924382. PMID 20808860.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Bhate K, Williams HC (April 2014). "What's new in acne? An analysis of systematic reviews published in 2011-2012". Clinical and experimental dermatology 39 (3): 273–7. doi:10.1111/ced.12270. PMID 24635060.

- ↑ Davidovici, Batya B.; Wolf, Ronni (2010). "The role of diet in acne: Facts and controversies". Clinics in Dermatology 28 (1): 12–6. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.03.010. PMID 20082944.

- ↑ Melnik, BC; John, SM; Plewig, G (November 2013). "Acne: risk indicator for increased body mass index and insulin resistance". Acta dermato-venereologica 93 (6): 644–9. doi:10.2340/00015555-1677. PMID 23975508.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Ferdowsian HR, Levin S (March 2010). "Does diet really affect acne?". Skin therapy letter 15 (3): 1–2, 5. PMID 20361171.

- ↑ Melnik, Bodo C. (2011). "Evidence for Acne-Promoting Effects of Milk and Other Insulinotropic Dairy Products". Milk and Milk Products in Human Nutrition. Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop Series: Pediatric Program 67. p. 131. doi:10.1159/000325580. ISBN 978-3-8055-9587-2.

- ↑ Melnik, Bodo C.; Schmitz, Gerd (2009). "Role of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1, hyperglycaemic food and milk consumption in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris". Experimental Dermatology 18 (10): 833–41. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00924.x. PMID 19709092.

- ↑ Cordain L (June 2005). "Implications for the Role of Diet in Acne". Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 24 (2): 84–91. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2005.04.002. PMID 16092796.

- ↑ Brescoll, J; Daveluy, S (February 2015). "A review of vitamin B12 in dermatology.". American journal of clinical dermatology 16 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0107-3. PMID 25559140.

- ↑ Chiu A, Chon SY, Kimball AB (July 2003). "The Response of Skin Disease to Stress". Archives of Dermatology 139 (7): 897–900. doi:10.1001/archderm.139.7.897. PMID 12873885.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers about Acne". http://www.niams.nih.gov/''. May 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Sieber, MA; Hegel, JK (November 2013). "Azelaic acid: Properties and mode of action". Skin Pharmacol Physiol 27 (Supplement 1): 9–17. doi:10.1159/000354888. PMID 24280644.

- ↑ Simpson, Nicholas B.; Cunliffe, William J. (2004). "Disorders of the sebaceous glands". In Burns, Tony; Breathnach, Stephen; Cox, Neil; Griffiths, Christopher. Rook's textbook of dermatology (7th ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Science. pp. 43.1–75. ISBN 0-632-06429-3.

- ↑ Leeds, Cook's and Pillsbury scales obtained from here

- ↑ Archer CB, Cohen SN, Baron SE; British Association of Dermatologists and Royal College of General Practitioners (May 2012). "Guidance on the diagnosis and clinical management of acne". Clinical and experimental dermatology 37 (Supplement 1): 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04335.x. PMID 22486762.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Ramos-e-Silva M, Carneiro SC (March 2009). "Acne vulgaris: Review and guidelines". Dermatology nursing/Dermatology Nurses' Association 21 (2): 63–8; quiz 69. PMID 19507372.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Simonart T (December 2012). "Newer approaches to the treatment of acne vulgaris". America Journal of Clinical Dermatology 13 (6): 357–64. doi:10.2165/11632500-000000000-00000. PMID 22920095.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 Sagransky, Matt; Yentzer, Brad A; Feldman, Steven R (2009). "Benzoyl peroxide: A review of its current use in the treatment of acne vulgaris". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 10 (15): 2555–62. doi:10.1517/14656560903277228. PMID 19761357.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Madan RK, Levitt J (April 2014). "A review of toxicity from topical salicylic acid preparations". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 70 (4): 788–92. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.005. PMID 24472429.

- ↑ Well D (October 2013). "Acne vulgaris: A review of causes and treatment options". The Nurse practitioner 38 (10): 22–31. doi:10.1097/01.NPR.0000434089.88606.70. PMID 24048347.

- ↑ Morelli, Vincent; Calmet, Erick; Jhingade, Varalakshmi (2010). "Alternative Therapies for Common Dermatologic Disorders, Part 2". Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice 37 (2): 285–96. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2010.02.005. PMID 20493337.

- ↑ "Azelaic Acid Topical". National Institutes Of Health. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Arowojolu, Ayodele O; Gallo, Maria F; Lopez, Laureen M; Grimes, David A (2012). Arowojolu, Ayodele O, ed. "Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7: CD004425. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004425.pub6. PMID 22786490.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Pugashetti, R; Shinkai, K (July 2013). "Treatment of acne vulgaris in pregnant patients". Dermatol Ther 26 (4): 302–11. doi:10.1111/dth.12077. PMID 23914887.

- ↑ Hamilton, F.L.; Car, J.; Lyons, C.; Car, M.; Layton, A.; Majeed, A. (2009). "Laser and other light therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris: Systematic review". British Journal of Dermatology 160 (6): 1273–85. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09047.x. PMID 19239470.

- ↑ Chapas, Anne M.; Brightman, Lori; Sukal, Sean; Hale, Elizabeth; Daniel, David; Bernstein, Leonard J.; Geronemus, Roy G. (2008). "Successful treatment of acneiform scarring with CO2 ablative fractional resurfacing". Lasers in Surgery and Medicine 40 (6): 381–6. doi:10.1002/lsm.20659. PMID 18649382.

- ↑ Ong, MW; Bashir, SJ (June 2012). "Fractional laser resurfacing for acne scars: a review". Br J Dermatol 166 (6): 1160–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10870.x. PMID 22296284.

- ↑ Cao, Huijuan; Yang, Guoyan; Wang, Yuyi; Liu, Jian Ping; Smith, Caroline A; Luo, Hui; Liu, Yueming; Liu, Jian Ping (2015). "Complementary therapies for acne vulgaris". doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009436.pub2.

- ↑ Yarnell, Eric; Abascal, Kathy (2006). "Herbal Medicine for Acne Vulgaris". Alternative and Complementary Therapies 12 (6): 303–9. doi:10.1089/act.2006.12.303.

- ↑ Pazyar, Nader; Yaghoobi, Reza; Bagherani, Nooshin; Kazerouni, Afshin (2013). "A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology". International Journal of Dermatology 52 (7): 784–90. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05654.x. PMID 22998411.

- ↑ Costa, CS; Bagatin, E (2013). "Evidence on acne therapy". Sao Paulo medical journal = Revista paulista de medicina 131 (3): 193–7. PMID 23903269.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Vos, Theo; Flaxman (2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". The Lancet 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMID 23245607.

- ↑ Shah, Sejal K.; Alexis, Andrew F. (2010). "Acne in skin of color: Practical approaches to treatment". Journal of Dermatological Treatment 21 (3): 206–11. doi:10.3109/09546630903401496. PMID 20132053.

- ↑ White GM (August 1998). "Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 39 (2): S34–37. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70442-6. PMID 9703121.

- ↑ Keri J, Shiman M (2009). "An update on the management of acne vulgaris". Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 17 (2): 105–10. PMC 3047935. PMID 21436973.

- ↑ Myra Michelle Eby, Michelle Eby Myra. Return to Beautiful Skin. Basic Health Publications. p. 275.

- ↑ "Tretinoin (retinoic acid) in acne". The Medical letter on drugs and therapeutics 15 (1): 3. 1973. PMID 4265099.

- ↑ Jones, H (1980). "13-Cis Retinoic Acid and Acne". The Lancet 316 (8203): 1048–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(80)92273-4. PMID 6107678.

- ↑ Bérard, Anick; Azoulay, Laurent; Koren, Gideon; Blais, Lucie; Perreault, Sylvie; Oraichi, Driss (2007). "Isotretinoin, pregnancies, abortions and birth defects: A population-based perspective". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 63 (2): 196–205. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02837.x. PMC 1859978. PMID 17214828.

- ↑ Holmes, SC; Bankowska, U; MacKie, RM (1998). "The prescription of isotretinoin to women: Is every precaution taken?". British Journal of Dermatology 138 (3): 450–55. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02123.x. PMID 9580798.

- ↑ Brown MM, Chamlin SL, Smidt AC (April 2013). "Quality of life in pediatric dermatology". Dermatologic Clinics 31 (2): 211–21. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.12.010. PMID 23557650.

- ↑ Farrar, M. D.; Howson, K. M.; Bojar, R. A.; West, D.; Towler, J. C.; Parry, J.; Pelton, K.; Holland, K. T. (2007). "Genome Sequence and Analysis of a Propionibacterium acnes Bacteriophage". Journal of Bacteriology 189 (11): 4161–67. doi:10.1128/JB.00106-07. PMC 1913406. PMID 17400737.

- ↑ Kao M, Huang CM. "Acne vaccines targeting Propionibacterium acnes". Giornale italiano di dermatologia e venerologia 144 (6): 639–43. PMID 19907403.

- ↑ MacKenzie, D. (September 23, 2011). In development: a vaccine for acne. New Scientist archive. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

External links

- Questions and Answers about Acne - US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

![]() Media related to Acne at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Acne at Wikimedia Commons

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||