Acipenser oxyrinchus

| Acipenser oxyrinchus | |

|---|---|

| |

| A. o. oxyrinchus | |

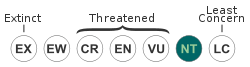

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Acipenseriformes |

| Family: | Acipenseridae |

| Genus: | Acipenser |

| Species: | A. oxyrhynchus |

| Binomial name | |

| Acipenser oxyrhynchus Mitchill, 1815 | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Acipenser oxyrinchus desotoi | |

Acipenser oxyrinchus is a species of sturgeon.

Information

Acipenser oxyrinchus is a species with two subspecies:

- Atlantic sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus.

- Gulf sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrinchus desotoi.

Their main diet includes crustaceans, worms, and mollusks. This species is also known to migrate up the river when it is spawning.[2] This species is also recorded to be near threatened of becoming an endangered species due to dam construction, dredging, dredge spoil disposal, groundwater extraction, irrigation and other surface water withdrawals, and flow alterations. The Acipenser oxyrinchus is native to the countries of Canada and the United States.[3] They can be found in sub-tropical climates and in a marine, freshwater environment.[4]

Characteristics

The Acipenser oxyrinchus can grow to the average length of 14 feet and the average weight of 800 pounds. The lifespan of this species can be around 60 years. The color of the Acipenser oxyrinchus is bluish-black or olive brown with lighter sides and a white belly.

Behavior

Sturgeon are an anadromous species that live solitarily or in small groups. They migrate upriver in the spring to spawn. Sturgeons tend to inhabit the shallow waters of coastal shelves, coastal and estuarine areas on soft bottom in the sea, and can live down to a depth of 50 meters. Adults are migratory while at sea and will make long migrations to coastal areas, while juveniles will stay in fresh or brackish water until they are between two to five years of age. However, many larvae and juveniles do start to migrate and disperse small distances from their spawning sites.[5]

Migration

Sturgeons will migrate upriver to spawn. Sturgeons from the Gulf of Mexico will naturally exhibit spawning migration in the spring. Peak numbers have been observed in March and April, which is when the fish will migrate into the Suwanee River in Florida.[6] Sturgeon will migrate downstream for twelve days, peaking within the first six days. Atlantic sturgeons only need to move a short distance to reach rearing areas. Early sturgeon migrants tend to be nocturnal while later migrants are diurnal.[7] During summer months, sturgeon will remain in localized bottom areas of the rivers. In the late fall, the sturgeon migrate out of spawning rivers and into the Gulf of Mexico.[6]

For all populations and subspecies of sturgeon, there are spawning migrations into freshwater in early spring and movement into salt water in the fall. Timing and the unusual migratory behavior of sturgeon is a result of temporal water temperature changes.[6] Studies have also shown that amongst sturgeon in Gulf of Mexico and Suwannee River in Florida, fish gained 20% of their body weight while in Gulf of Mexico and lost 12% of their body weight during their time in the river.[8]

Spawning

The maximum level of survival for eggs, embryos, and larvae is at 15 to 20°C. Studies have shown that high mortalities are seen at temperatures of 25°C or higher.[6] In order for spawning to occur, water temperature should be above 17°C. Spawning normally lasts between nine and twenty-three days, but can continue past this as long as the water temperature remains below 22C.[9]

Free sturgeon embryos (the first interval of sturgeon after hatching) hide under rocks and do not migrate. They are found in the freshwater spawning areas. Larvae and some juveniles start to migrate slowly for about five months downstream. This leads to a wide dispersal of the fish.[10] Typically, the entire freshwater reach of the river downstream from the actual spawning site is so filled with larva-juvenile individuals that it is considered to be a nursery habitat.[10]

Sturgeon populations will use the same spawning reefs from year to year. Habitat factors that can help determine spawning sites include the presence of gravel substrate, presence of eddy fields, slightly basic pH, and a range in calcium ion content. Eggs are usually deposited in a small area and scatter very little. It is not until larvae and juveniles start to migrate that the fish disperse widely.[9]

Body color

Some evidence has shown that developmental body color is related to migration style. Free embryos are light and are non-migratory, while migratory larvae and adults are dark. This is found to be consistent among many Acipenser species. The reason for this is unclear, but it may be adaptive to migration behavior and camouflage.[10]

Diet

The primary foods of sturgeon while in freshwater areas include soft-bodied annelids, arthropods, aquatic insects, and globular mollusks. Adults that have emigrated from estuaries and into the sea will usually feed on epibenthic and hyperbenthic amphipods, grass shrimp, isopods, and worms. Most adult sturgeon will also feed on detritus and biofilm.[11] Sturgeons are most generally known for feeding on crustaceans, worms, and molluscs.[12]

Larvae-juvenile feeding was at the bottom, benthic foraging. However, food in the benthic zone is scarce, so many adapt drift feeding, in which they have holding positions in the water column and wait for food.[10] Sturgeons may have dominance hierarchies with large fish being dominant when competing for limited foraging space.[7]

Habitat

Sturgeons are widely distributed along the Atlantic coast of the United States. Their wide distribution and tendency to disperse has led to numerous subspecies of sturgeon.[12]

In general, sturgeons usually inhabit primarily the temperate waters of the northern hemisphere. Gulf of Mexico sturgeons are probably adapted to warmer water temperatures. Due to sturgeons' predilection for cooler waters, when water temperatures rise too high, sturgeon will try to find cool spring waters which serve as thermal refuges until temperatures drop again.[6]

Susceptibility to anthropogenic disturbances

There are many wide-ranging subspecies along the Atlantic Coast of North America. Identification of distinct population segments (DPS) is problematic because of sturgeons' ability to disperse so widely. However, it is possible to do some characterization of genetic differentiation and estimate gene flow. This method has been used to determine possibility for listing under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.[13]

The sturgeon’s characteristics and life history make it susceptible to anthropogenic disturbances and make population restoration particularly difficult. They have late sexual maturity, only moderate fecundity, and spawn at low frequencies. Females spawn once every three to five years, and males every one to five years. This is due to their ability to live for an extremely long time (various sub-species can have a lifespan ranging from ten years to sixty years).[13]

The population of Atlantic sturgeons has decreased dramatically in the past century due to overharvesting. They are particularly susceptible to bycatch mortality due to the many fisheries that exist within their natal estuaries. Their habitat range, which usually includes coastal spawning sites and coastal migrations, makes sturgeon well within contact of coastal fisheries.[13]

Effects of hypoxia

Hypoxia combined with high water temperatures in the summer has been shown to be consistent with decreased survival rates of young of the year sturgeon in Chesapeake Bay.[14]

Hypoxia is defined as low ambient oxygen levels, which may be very harmful to organisms living in the hypoxic body of water. Often, lower regions of the water column will be more hypoxic than upper levels, closer to the surface. When surface access is denied, the situation is lethal to sturgeon. Increased incidences of summertime hypoxia have led, in part, to degradation of many sturgeon nursery habitats in the United States.[14]

References

- ↑ St. Pierre, R. & Parauka, F.M. (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service) (2006). Acipenser oxyrinchus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ↑ "Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus)". NOAA Fisheries. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ "Acipenser oxyrinchus". International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ "Acipenser oxyrinchus". Fish Base. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer. "Acipenser oxyrinchus". Fish Base. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Chapman, Frank A.; Stephen H. Carr (August 1995). "Implications of early life stages in the natural history of the Gulf of Mexico sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrinchus de sotoi". Environmental Biology of Fishes 43 (4): 407–413. doi:10.1007/bf00001178. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kynard, Boyd; Martin Horgan (February 2002). "Ontogenetic Behavior and Migration of Atlantic Sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus, and Shortnose Sturgeon, A. brevirostrum, with Notes on Social Behavior". Environmental Biology of Fishes 63 (2): 137–150. doi:10.1023/A:1014270129729. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ↑ Carr, S.H.; F. Tatman; F. A. Chapman (December 1996). "Observations on the natural history of the Gulf of Mexico sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus de sotoi Vladykov 1955) in the Suwannee River, southeastern United States". Ecology of Freshwater Fish 5 (4): 169–174. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0633.1996.tb00130.x.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sulak, K.J.; J.P. Clugston (September 1999). "Recent advances in life history of Gulf of Mexico sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrinchus desotoi, in the Suwannee river, Florida, USA: a synopsis". Journal of Applied Ichthyology 15 (4-5): 116–128. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0426.1999.tb00220.x. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Kynard, Boyd; Erika Parker (May 2004). "Ontogenetic Behavior and Migration of Gulf of Mexico Sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrinchus desotoi, with Notes on Body Color and Development". Environmental Biology of Fishes 70 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1023/b:ebfi.0000022855.96143.95. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ Mason Jr., William T.; James P. Clugston (1993). "Foods of the Gulf Sturgeon in the Suwannee River, Florida". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 122 (3): 378–385. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1993)122<0378:fotgsi>2.3.co;2. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus)". NOAA Fisheries Office of Protected Resources. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Grunwald, Cheryl; Lorraine Maceda; John Waldman; Joseph Stabile; Isaac Wirgin (October 2008). "Conservation of Atlantic sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus: delineation of stock structure and distinct population segments". Conservation Genetics 9 (5): 1111–1124. doi:10.1007/s10592-007-9420-1. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Secor, David H.; Troy E. Gunderson (1998). "Effects of hypoxia and temperature on survival, growth, and respiration of juvenile Atlantic sturgeon, Acipenser oxyrinchus" 96 (3). pp. 603–613. Retrieved 24 October 2013.