Achaemenid Empire

| Achaemenid Empire | |||||

| | |||||

| |||||

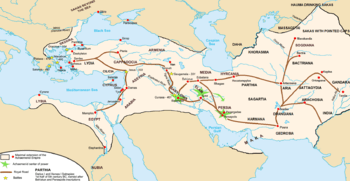

Achaemenid territorial expansion and greatest extent. | |||||

| Capital | Babylon[1] (main capital), Pasargadae, Ecbatana, Susa, Persepolis | ||||

| Languages | Persian[a] Old Aramaic language[b] Akkadian[2] Median Old Greek(Administrative)[3] Elamite Sumerian[c] | ||||

| Religion | Zoroastrianism, Babylonian[4] | ||||

| Government | Feudal Monarchy | ||||

| xšāyaϑiya or xšāyaϑiya xšāyaϑiyānām king or king of kings | |||||

| - | 559–529 BCE | Cyrus the Great | |||

| - | 336–330 BCE | Darius III | |||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity | ||||

| - | Persian Revolt | 550 BCE | |||

| - | Conquest of Lydia | 547 BCE | |||

| - | Conquest of Babylon | 539 BCE | |||

| - | Conquest of Egypt | 525 BCE | |||

| - | Greco-Persian Wars | 499–449 BCE | |||

| - | Fall to Macedonia | 330 BCE | |||

| Area | |||||

| - | 500 BCE | 8,000,000 km² (3,088,817 sq mi) | |||

| Population | |||||

| - | 500 BCE est.[5] | 50,000,000 | |||

| Density | 6.3 /km² (16.2 /sq mi) | ||||

| Currency | Daric, Siglos | ||||

| Today part of | Countries today

| ||||

| a. ^ Native language. b. ^ Official language and lingua franca.[9] c. ^ Literary language in Babylonia. | |||||

The Achaemenid Empire (/əˈkiːmənɪd/; Old Persian:![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() [10] <PA-A-RA-SA> Pārsa;[11][12] New Persian: شاهنشاهی هخامنشی c. 550–330 BC), also called the First Persian Empire[13] or Medo-Persian Empire, was an empire based in Western Asia in Iran, founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great.[13] The dynasty draws its name from a hypothetical king Achaemenes, who would have ruled the Persis region between 705 BCE and 675 BCE. The empire expanded to eventually rule over significant portions of the ancient world, which at around 500 BCE stretched from parts of the Balkans and Thrace-Macedonia in the west, to the Indus valley in the east.[14] The Achaemenid Empire would eventually control Egypt as well. It was ruled by a series of hereditary monarchs who found a way to help unify its disparate tribes and nationalities by constructing a complex network of roads.

[10] <PA-A-RA-SA> Pārsa;[11][12] New Persian: شاهنشاهی هخامنشی c. 550–330 BC), also called the First Persian Empire[13] or Medo-Persian Empire, was an empire based in Western Asia in Iran, founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great.[13] The dynasty draws its name from a hypothetical king Achaemenes, who would have ruled the Persis region between 705 BCE and 675 BCE. The empire expanded to eventually rule over significant portions of the ancient world, which at around 500 BCE stretched from parts of the Balkans and Thrace-Macedonia in the west, to the Indus valley in the east.[14] The Achaemenid Empire would eventually control Egypt as well. It was ruled by a series of hereditary monarchs who found a way to help unify its disparate tribes and nationalities by constructing a complex network of roads.

By the 600s BCE, the Persians (pārsa)[15] had settled in the region in the southwestern portion of the Iranian plateau, in what came to be known as Persis ("city of Persians") bounded on the west by the Tigris River and on the south by the Persian Gulf; this region came to be their heartland.[14] It was from this region that Cyrus the Great would advance to defeat the Kingdom of Media, the Kingdom of Lydia, and the Babylonian Empire, to form the Achaemenid Empire. At the height of its power after the conquest of ancient Egypt, the empire encompassed approximately 8 million square kilometers[16] spanning three continents: Asia, Europe and Africa. At its greatest extent, the empire included the modern territories of Iran, Turkey, Iraq, Kuwait, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, all significant population centers of ancient Egypt as far west as Libya, Thrace and the ancient kingdom of Macedonia, much of the Black Sea coastal regions, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, much of Central Asia, Afghanistan, China, northern Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and parts of Oman and the UAE.[7][8]

In 480 BCE, it is estimated that 50 million[5] people lived in the Achaemenid Empire.[17] According to Guinness World Records, the empire at its peak ruled over 44% of the world's population, the highest such figure for any empire in history.[18] It is noted in Western history as the antagonist of the Greek city states[14] during the Greco-Persian Wars, for emancipation of slaves including the Jewish exiles in Babylon, and for building infrastructure such as a postal system and road systems, and the use of an official language, Aramaic, throughout its territories. The empire had a centralised, bureaucratic administration under a king and a large professional army and civil services, inspiring similar systems in later empires.[19]

The delegation of power to local governments is thought to have eventually weakened the king's authority, causing resources to be expended in attempts to subdue local rebellions, and leading to the disunity of the region at the time of Alexander the Great's invasion in 334 BCE.[14] This viewpoint, however, is challenged by some modern scholars who argue that the Achaemenid Empire was not facing any such crisis around the time of Alexander, and that only internal succession struggles within the Achaemenid family ever came close to weakening the empire.[14] Alexander, an avid admirer of Cyrus the Great,[20] would eventually cause the collapse of the empire and its disintegration around 330 BCE into what later became the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Seleucid Empire, in addition to other minor territories which gained independence at that time. However, the Persian population of the central plateau continued to thrive and eventually reclaimed power by the 2nd century BCE.[14]

The historical mark of the Achaemenid Empire went far beyond its territorial and military influences and included cultural, social, technological and religious influences as well. Many Athenians adopted Achaemenid customs in their daily lives in a reciprocal cultural exchange,[21] some being employed by, or allied to the Persian kings. The impact of Cyrus the Great's Edict of Restoration is mentioned in Judeo-Christian texts and the empire was instrumental in the spread of Zoroastrianism as far east as China. Even Alexander the Great adopted some of its customs, venerating the Persian kings including Cyrus the Great, and receiving proskynesis as they did, despite Macedonian disapproval.[22][23] The Persian Empire would also set the tone for the politics, heritage and history of modern Persia (now called Iran).[24]

History

Achaemenid timeline

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Iran |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Related articles |

| Iran portal |

Origin

The Persian nation contains a number of tribes as listed here. ... : the Pasargadae, Maraphii, and Maspii, upon which all the other tribes are dependent. Of these, the Pasargadae are the most distinguished; they contain the clan of the Achaemenids from which spring the Perseid kings. Other tribes are the Panthialaei, Derusiaei, Germanii, all of which are attached to the soil, the remainder -the Dai, Mardi, Dropici, Sagarti, being nomadic.

The Persian Empire was created by nomadic Persians who originally referred to themselves as parsua. The name Persia is a Greek and Latin pronunciation of the name Parsua, referring to people originating from Persis (or in Persian, Pars), their home territory located north of the Persian Gulf in south western Iran.[25]

Despite its success and rapid expansion, the Achaemenid Empire was not the first Iranian empire, as by 6th century BCE another group of ancient Iranian peoples had already established the Median Empire.[25] The Medes had originally been the dominant Iranian group in the region, rising to power at the end of the 7th century BC and incorporating the Persians into their empire. The Iranian people had arrived in the region circa 1000 BCE[26] and had initially fallen under the domination of the Assyrian Empire (911-609 BCE). However, the Medes and Persians (together with the Scythians and Babylonians) played a major role in the defeat of the Assyrians and establishment of the first Persian empire.

The term Achaemenid is in fact the Latinized version of the Old Persian name Haxāmaniš (a bahuvrihi compound translating to "having a friend's mind"[27]), meaning in Greek "of the family of the Achaemenis." Despite the derivation of the name, Achaemenes was himself a minor 7th-century ruler of the Anshan (Ansham or Anšān) located in southwestern Iran.[25] It was not until the time of Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II of Persia), a descendant of Achaemenes, that the Achaemenid Empire developed the prestige of an empire and set out to incorporate the existing empires of the ancient east, becoming the vast Persian Empire of ancient legend.

At some point in 550 BCE, Cyrus the Great rose in rebellion against the Median Empire (most likely due to the Medes' mismanagement of Persis), eventually conquering the Medes and creating the first Persian empire. Cyrus the Great utilized his tactical genius,[28] as well as his understanding of the socio-political conditions governing his territories, to eventually incorporate into the Persian Empire the neighbouring Lydian and Neo-Babylonian empires, also leading the way for his successor, Cambyses II, to venture into Egypt and defeat the Egyptian Kingdom.

Cyrus the Great's political acumen was reflected in his management of his newly formed empire, as the Persian Empire became the first to attempt to govern many different ethnic groups on the principle of equal responsibilities and rights for all people, so long as subjects paid their taxes and kept the peace.[29] Additionally, the king agreed not to interfere with the local customs, religions, and trades of its subject states,[29] a unique quality that eventually won Cyrus the support of the Babylonians. This system of management ultimately became an issue for the Persians, as with a larger empire came the need for order and control, leading to expenditure of resources and mobilization of troops to quell local rebellions, and weakening the central power of the king. By the time of Darius III, this disorganization had almost led to a disunited realm.[14]

The Persians from whom Cyrus hailed were originally nomadic pastoral people in the western Iranian plateau and by 850 BC were calling themselves the Parsa and their constantly shifting territory Parsua, for the most part localized around Persis (Pars).[14] As Persians gained power, they developed the infrastructure to support their growing influence, including creation of a capital named Pasargadae and an opulent city named Persepolis.

Begun during the rule of Darius the Great (Darius I) and completed some 100 years later,[30] Persepolis was a symbol of the empire serving both as a ceremonial centre and a center of government.[30] It had a special set of gradually progressive stairways named "All Countries"[30] around which carved relief decoration depicted scenes of heroism, hunting, natural themes, and presentation of the gifts to the Achaemenid kings by their subjects during the spring festival, Nowruz. The core structure was composed of a multitude of square rooms or halls, the biggest of which was called Apadana.[30] Tall, decorated columns welcomed visitors and emphasized the height of the structure. Later on, Darius the Great (Darius I) also utilized Susa and Ecbatana as his governmental centres, developing them to a similar metropolitan status.

Accounts of the ancestral lineage of the Persian kings of the Achaemenid dynasty can be derived from either documented Greek or Roman accounts, or from existing documented Persian accounts such as those found in the Behistun Inscription. However, since most existing accounts of this vast empire are in works of Greek philosophers and historians, and since many of the original Persian documents are lost, not to mention being subject to varying scholarly views on their origin and possible motivations behind them, it is difficult to create a definitive and completely objective list. Nonetheless, it is clear that Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II of Persia) and Darius the Great (Darius I of Persia) were critical in the expansion of the empire. Cyrus the Great is often believed to be the son of Cambyses I, grandson of Cyrus I, the father of Cambyses II, and a relative of Darius the Great, through a shared ancestor, Teispes. Cyrus the Great is also believed to have been a family member (possibly grandson) of the Median king Astyages through his mother, Mandana of Media. A minority of scholars argue that perhaps Achaemenes was a retrograde creation of Darius the Great, in order to reconcile his connection with Cyrus the Great after gaining power.[25]

Ancient Greek writers provide some legendary information about Achaemenes by calling his tribe the Pasargadae and stating that he was "raised by an eagle". Plato, when writing about the Persians, identified Achaemenes with Perses, ancestor of the Persians in Greek mythology.[31] According to Plato, Achaemenes was the same person as Perses, a son of the Ethiopian queen Andromeda and the Greek hero Perseus, and a grandson of Zeus. Later writers believed that Achaemenes and Perses were different people, and that Perses was an ancestor of the king.[32] This account further confirms that Achaemenes could well have been a significant Anshan leader and an ancestor of Cyrus the Great. Regardless, both Cyrus the Great and Darius the Great were related, prominent kings of Persia, under whose rule the empire expanded to include much of the ancient world.

Formation and expansion

The empire took its unified form with a central administration around Pasargadae erected by Cyrus the Great. The empire ended up conquering and enlarging the Median Empire to include in addition Egypt and Asia Minor. During the reigns of Darius I and his son Xerxes I it engaged in military conflict with some of the major city-states of Ancient Greece, and although it came close to defeating the Greek army this war ultimately led to the empire's overthrow.[33]

In 559 BCE, Cambyses I the Elder was succeeded as the king of Anšān by his son Cyrus II the Great, who also succeeded the still-living Arsames as the King of Persia, thus reuniting the two realms. Cyrus is considered to be the first true king of the Persian Empire, as his predecessors were subservient to the Medes. Cyrus the Great conquered Media, Lydia, and Babylon. Cyrus was politically shrewd, modeling himself as the "savior" of conquered nations, often allowing displaced people to return, and giving his subjects freedom to practice local customs. To reinforce this image, he instituted policies of religious freedom, and restored temples and other infrastructure in the newly acquired cities (Most notably the Jewish inhabitants of Babylon, as recorded in the Cyrus Cylinder and the Tanakh). As a result of his tolerant policies he came to be known by those of the Jewish faith, as "the anointed of the Lord."[34][35]

His immediate successors were less successful. Cyrus' son Cambyses II conquered Egypt in 525 BCE, but died in July 522 BCE during a revolt led by a sacerdotal clan that had lost its power following Cyrus' conquest of Media. The cause of his death remains uncertain, although it may have been the result of an accident.[36]

According to Herodotus, Cambyses II had originally ventured into Egypt to take revenge for the pharaoh Amasis's trickery when he sent a fake Egyptian bride whose family Amasis had murdered,[37] instead of his own daughter, to wed Cambyses II. Additionally negative reports of mistreatment caused by Amasis, given by Phanes of Halicarnassus, a wise counsellor serving Amasis, further enforced Cambyses's resolve to venture into Egypt. Amasis died before Cambyses II could face him, but his successor Psamtik III was defeated by Cambyses II in the Battle of Pelusium.

While Cambyses II was in Egypt, the Zoroastrian priests, whom Herodotus called Magi, usurped the throne for one of their own, Gaumata, who then pretended to be Cambyses II's younger brother Bardiya (Greek: Smerdis or Tanaoxares/Tanyoxarkes[36]), who had been assassinated some three years earlier. Owing to the strict rule of Cambyses II, especially his stance on taxation,[38] and his long absence in Egypt, "the whole people, Perses, Medes and all the other nations," acknowledged the usurper, especially as he granted a remission of taxes for three years (Herodotus iii. 68). Cambyses II himself would not be able to quell the imposters, as he died on the way back from Egypt.

The claim that Gaumata had impersonated Bardiya (Smerdis), is derived from Darius the Great and the records at the Behistun Inscription. Historians are divided over the possibility that the story of the impostor was invented by Darius as justification for his coup.[39] Darius made a similar claim when he later captured Babylon, announcing that the Babylonian king was not, in fact, Nebuchadnezzar III, but an impostor named Nidintu-bel.[40]

According to the Behistun Inscription, Gaumata ruled for seven months before being overthrown in 522 BCE by Darius the Great (Darius I) (Old Persian Dāryavuš "Who Holds Firm the Good", also known as Darayarahush or Darius the Great). The Magi, though persecuted, continued to exist, and a year following the death of the first pseudo-Smerdis (Gaumata), saw a second pseudo-Smerdis (named Vahyazdāta) attempt a coup. The coup, though initially successful, failed.[41]

Herodotus writes[42] that the native leadership debated the best form of government for the empire. It was agreed that an oligarchy would divide them against one another, and democracy would bring about mob rule resulting in a charismatic leader resuming the monarchy. Therefore, they decided a new monarch was in order, particularly since they were in a position to choose him. Darius I was chosen monarch from among the leaders. He was cousin to Cambyses II and Bardiya (Smerdis), claiming Ariaramnes as his ancestor.

The Achaemenids thereafter consolidated areas firmly under their control. It was Cyrus the Great and Darius the Great who, by sound and farsighted administrative planning, brilliant military maneuvering, and a humanistic world view, established the greatness of the Achaemenids and, in less than thirty years, raised them from an obscure tribe to a world power. It was during the reign of Darius the Great (Darius I) that Persepolis was built (518–516 BC) and which would serve as capital for several generations of Achaemenid kings. Ecbatana (Hagmatāna "City of Gatherings", modern: Hamadan) in Media was greatly expanded during this period and served as the summer capital.

Darius the Great (Darius I) eventually attacked the Greek mainland, which had supported rebellious Greek colonies under his aegis; but as a result of his defeat at the Battle of Marathon, he was forced to pull the limits of his empire back to Asia Minor. Some scholars argue that in the context of history of the Near and Middle east in the first millennium, Alexander can be considered as the "last of the Achaemenids."[43] This is partly because Alexander maintained more or less the same political structure, and borders as the previous Achaemenid kings.

By the 5th century BC the Kings of Persia were either ruling over or had subordinated territories encompassing not just all of the Persian Plateau and all of the territories formerly held by the Assyrian Empire (Mesopotamia, the Levant, Cyprus and Egypt), but beyond this all of Anatolia and the Armenian Plateau as well as much of the Southern Caucasus, Macedonia and parts of Greece and Thrace to the north and west, parts of Central Asia as far as the Aral Sea, the Oxus and Jaxartes to the north and north-east, the Hindu Kush and the western Indus basin (corresponding to modern Afghanistan and Pakistan) to the east, parts of northern Arabia to the south and parts of northern Libya to the south-west.[44][45]

Greco-Persian Wars

The Ionian Revolt in 499 BCE, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 to 493 BCE. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisfaction of the Greek cities of Asia Minor with the tyrants appointed by Persia to rule them, along with the individual actions of two Milesian tyrants, Histiaeus and Aristagoras. In 499 BCE, the then tyrant of Miletus, Aristagoras, launched a joint expedition with the Persian satrap Artaphernes to conquer Naxos, in an attempt to bolster his position in Miletus (both financially and in terms of prestige). The mission was a debacle, and sensing his imminent removal as tyrant, Aristagoras chose to incite the whole of Ionia into rebellion against the Persian king Darius the Great.

The Persians continued to reduce the cities along the west coast that still held out against them, before finally imposing a peace settlement in 493 BCE on Ionia that was generally considered to be both just and fair. The Ionian Revolt constituted the first major conflict between Greece and the Achaemenid Empire, and as such represents the first phase of the Greco-Persian Wars. Asia Minor had been brought back into the Persian fold, but Darius had vowed to punish Athens and Eretria for their support of the revolt.[46] Moreover, seeing that the political situation in Greece posed a continued threat to the stability of his Empire, he decided to embark on the conquest of all of Greece. However, the Persian forces were defeated at the Battle of Marathon and Darius would die before having the chance to launch an invasion of Greece.

Xerxes I (485–465 BCE, Old Persian Xšayārša "Hero Among Kings"), son of Darius I, vowed to complete the job. He organized a massive invasion aiming to conquer Greece. His army entered Greece from the north, meeting little or no resistance through Macedonia and Thessaly, but was delayed by a small Greek force for three days at Thermopylae. A simultaneous naval battle at Artemisium was tactically indecisive as large storms destroyed ships from both sides. The battle was stopped prematurely when the Greeks received news of the defeat at Thermopylae and retreated. The battle was a strategic victory for the Persians, giving them uncontested control of Artemisium and the Aegean Sea.

Following his victory at the Battle of Thermopylae, Xerxes sacked the evacuated city of Athens and prepared to meet the Greeks at the strategic Isthmus of Corinth and the Saronic Gulf. In 480 BC the Greeks won a decisive victory over the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis and forced Xerxes to retire to Sardis. The land army which he left in Greece under Mardonius retook Athens but was eventually destroyed in 479 BCE at the Battle of Plataea. The final defeat of the Persians at Mycale encouraged the Greek cities of Asia to revolt, and marked the end of Persian expansion into Europe.

The cultural phase

Xerxes I was followed by Artaxerxes I (465–424 BCE), who moved the capital from Persepolis to Babylon. It was during this reign that Elamite ceased to be the language of government, and Aramaic gained in importance. It was probably during this reign that the solar calendar was introduced as the national calendar. Under Artaxerxes I, Zoroastrianism became the de facto religion of state, and for this Artaxerxes I is today also known as the Constantine of that faith.

Artaxerxes I died in Susa, and his body was brought to Persepolis for interment in the tomb of his forebearers. Artaxerxes I was immediately succeeded by his eldest son Xerxes II, who was however assassinated by one of his half-brothers a few weeks later. Darius II rallied support for himself and marched eastwards, executing the assassin and was crowned in his stead.

From 412 Darius II (423–404 BCE), at the insistence of the able Tissaphernes, gave support first to Athens, then to Sparta, but in 407 BCE, Darius' son Cyrus the Younger was appointed to replace Tissaphernes and aid was given entirely to Sparta which finally defeated Athens in 404 BCE. In the same year, Darius fell ill and died in Babylon. At his deathbed, his Babylonian wife Parysatis pleaded with Darius to have her second eldest son Cyrus (the Younger) crowned, but Darius refused.

Darius was then succeeded by his eldest son Artaxerxes II Memnon. Plutarch relates (probably on the authority of Ctesias) that the displaced Tissaphernes came to the new king on his coronation day to warn him that his younger brother Cyrus (the Younger) was preparing to assassinate him during the ceremony. Artaxerxes had Cyrus arrested and would have had him executed if their mother Parysatis had not intervened. Cyrus was then sent back as Satrap of Lydia, where he prepared an armed rebellion. Cyrus and Artaxerxes met in the Battle of Cunaxa in 401 BC, where Cyrus was killed.

Artaxerxes II (404–358 BCE), was the longest reigning of the Achaemenid kings and it was during this 45-year period of relative peace and stability that many of the monuments of the era were constructed. Artaxerxes moved the capital back to Persepolis, which he greatly extended. Also the summer capital at Ecbatana was lavishly extended with gilded columns and roof tiles of silver and copper (Polybius, 27 October 2012). The extraordinary innovation of the Zoroastrian shrine cults can also be dated to his reign, and it was probably during this period that Zoroastrianism was disseminated throughout Asia Minor and the Levant, from Armenia. The construction of temples, though serving a religious purpose, was however not a purely selfless act: as they also served as an important source of income. From the Babylonian kings, the Achaemenids had taken over the concept of a mandatory temple tax, a one-tenth tithe which all inhabitants paid to the temple nearest to their land or other source of income (Dandamaev & Lukonin, 1989:361–362). A share of this income called the quppu ša šarri, "kings chest"—an ingenious institution originally introduced by Nabonidus—was then turned over to the ruler. In retrospect, Artaxerxes is generally regarded as an amiable man who lacked the moral fibre to be a really successful ruler. However, six centuries later Ardeshir I, founder of the second Persian Empire, would consider himself Artaxerxes' successor, a grand testimony to the importance of Artaxerxes to the Persian psyche.

Fall of the empire

According to Plutarch, Artaxerxes' successor Artaxerxes III (358 – 338 BCE) came to the throne by bloody means, ensuring his place upon the throne by the assassination of eight of his half-brothers.[47] In 343 BCE Artaxerxes III defeated Nectanebo II, driving him from Egypt, and made Egypt once again a Persian satrapy. In 338 BCE Artaxerxes III died under unclear circumstances (natural causes according to cuneiform sources but Diodorus, a Greek historian, reports that Artaxerxes was murdered by Bagoas, his minister),[48] while Philip of Macedon united the Greek states by force and began to plan an invasion into the empire.

Artaxerxes III was succeeded by Artaxerxes IV Arses, who before he could act was also poisoned by Bagoas. Bagoas is further said to have killed not only all Arses' children, but many of the other princes of the land. Bagoas then placed Darius III (336–330 BCE), a nephew of Artaxerxes IV, on the throne. Darius III, previously Satrap of Armenia, personally forced Bagoas to swallow poison. In 334 BCE, when Darius was just succeeding in subduing Egypt again, Alexander and his battle-hardened troops invaded Asia Minor.

At two different times, the Achaemenids ruled Egypt although the Egyptians twice regained temporary independence from Persia. After the practice of Manetho, Egyptian historians refer to the periods in Egypt when the Achaemenid dynasty ruled as the twenty-seventh dynasty of Egypt, 525–404 BC, until the death of Darius II, and the thirty-first dynasty of Egypt, 343–332 BCE, which began after Nectanebo II was defeated by the Persian king Artaxerxes III.

Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) defeated the Persian armies at Granicus (334 BCE), followed by Issus (333 BCE), and lastly at Gaugamela (331 BCE). Afterwards, he marched on Susa and Persepolis which surrendered in early 330 BCE. From Persepolis, Alexander headed north to Pasargadae where he visited the tomb of Cyrus, the burial of the man whom he had heard of from Cyropedia.

In the ensuing chaos created by Alexander's invasion of Persia, Cyrus's tomb was broken into and most of its luxuries were looted. When Alexander reached the tomb, he was horrified by the manner in which it had been treated, and questioned the Magi, putting them on trial.[49][50] By some accounts, Alexander's decision to put the Magi on trial was more an attempt to undermine their influence and display his own power than a show of concern for Cyrus's tomb.[51] Regardless, Alexander the Great ordered Aristobulus to improve the tomb's condition and restore its interior, showing respect for Cyrus.[49] From there he headed to Ecbatana, where Darius III had sought refuge.

Darius III was taken prisoner by Bessus, his Bactrian satrap and kinsman. As Alexander approached, Bessus had his men murder Darius III and then declared himself Darius' successor, as Artaxerxes V, before retreating into Central Asia leaving Darius' body in the road to delay Alexander, who brought it to Persepolis for an honorable funeral. Bessus would then create a coalition of his forces, in order to create an army to defend against Alexander. Before Bessus could fully unite with his confederates at the eastern part of the empire,[52] Alexander, fearing the danger of Bessus gaining control, found him, put him on trial in a Persian court under his control, and ordered his execution in a "cruel and barbarous manner".[53]

Having conquered the Persian empire, Alexander was unable to offer a stable alternative.[54] When he died his empire was divided among his generals (the Diadochi), and succeeded by a number of smaller states, the largest of which was the Seleucid Empire, ruled by the generals of Alexander and their descendants. They in turn would be succeeded by the Parthian Empire.

Part of the cause of the Empire's decline had been the heavy tax burden put upon the state, which eventually led to economic decline.[55][56] An estimate of the tribute imposed on the subject nations was up to U.S. $180M per year. This does not include the material goods and supplies that were supplied as taxes.[57] After the high overhead of government - the military, the bureaucracy, whatever the satraps could safely dip into the coffers for themselves - this money went into the royal treasury. At Persepolis, Alexander III found some 180,000 talents, besides the additional treasure the Macedonians were carrying that already had been seized in Damascus by Parmenio.[58] This amounted to U.S. $2.7B. On top of this, Darius III had taken 8,000 talents with him on his flight to the north.[57] Alexander put this static hoard back into the economy, and upon his death some 130,000 talents had been spent on the building of cities, dockyards, temples, and the payment of the troops, besides the ordinary government expenses.[59] Additionally, one of the satraps, Harpalus, had made off to Greece with some 6,000 talents, which Athens used to rebuild its economy after seizing it during the struggles with the Corinthian League.[60] Due to the flood of money from Alexander's hoard entering Greece, however, a disruption in the economy occurred, in agriculture, banking, rents, the great increase in mercenary soldiers that cash allowed the wealthy, and an increase in piracy.[61]

Another factor contributing to the decline of the Empire after Xerxes was its failure to ever mold the many subject nations into a whole; the creation of a national identity was never attempted.[62] This lack of cohesion eventually affected the efficiency of the military.[63]

Descendants in later Iranian dynasties

Istakhr, one of the vassal kingdoms of the Parthian Empire, would be overthrown by Papak, a priest of the temple there. Papak's son, Ardašir I, who named himself in remembrance of Artaxerxes II, would revolt against the Parthians, eventually defeating them and establishing the Sassanid Empire or as it is known the second Persian Empire.

Both the later dynasties of the Parthians and Sasanians would on occasion claim Achaemenid descent. Recently there has been some corroboration for the Parthian claim to Achaemenid ancestry via the possibility of an inherited disease (neurofibromatosis) demonstrated by the physical descriptions of rulers and from evidence of familial disease on ancient coinage.[64]

Government

Cyrus the Great founded the empire as a multi-state empire, governed by four capital states; Pasargadae, Babylon, Susa and Ekbatana. The Achaemenids allowed a certain amount of regional autonomy in the form of the satrapy system. A satrapy was an administrative unit, usually organized on a geographical basis. A 'satrap' (governor) was the vassal king, who administered the region, a 'general' supervised military recruitment and ensured order, and a 'state secretary' kept the official records. The general and the state secretary reported directly to the satrap as well as the central government. At differing times, there were between 20 and 30 satrapies.[66]

Cyrus the Great created an organized army including the Immortals unit, consisting of 10,000 highly trained soldiers[67] Cyrus also formed an innovative postal system throughout the empire, based on several relay stations called Chapar Khaneh.[68]

Darius the Great reinforced the empire and expanded Persepolis as a ceremonial capital;[69] he revolutionized the economy by placing it on a silver and gold coinage and introducing a regulated and sustainable tax system that was precisely tailored to each satrapy, based on their supposed productivity and their economic potential. For instance, Babylon was assessed for the highest amount and for a startling mixture of commodities – 1000 silver talents, four months supply of food for the army. India was clearly already fabled for its gold; the province consisting of the sindh and western Punjab regions of ancient northwestern India traded gold dust equal in value to the very large amount of 4680 silver talents for various commodities. Egypt was known for the wealth of its crops; it was to be the granary of the Persian Empire (as later of Rome's) and was required to provide 120,000 measures of grain in addition to 700 talents of silver. This was exclusively a tax levied on subject peoples.[70] Other accomplishments of Darius' reign included codification of the data, a universal legal system, and construction of a new capital at Persepolis.

Under the Achaemenids, the trade was extensive and there was an efficient infrastructure that facilitated the exchange of commodities in the far reaches of the empire. Tariffs on trade were one of the empire's main sources of revenue, along with agriculture and tribute.[70][71]

The satrapies were linked by a 2,500-kilometer highway, the most impressive stretch being the Royal Road from Susa to Sardis, built by command of Darius I. The relays of mounted couriers could reach the remotest of areas in fifteen days. Despite the relative local independence afforded by the satrapy system, royal inspectors, the "eyes and ears of the king", toured the empire and reported on local conditions.

The practice of slavery in Achaemenid Persia was generally banned, although there is evidence that conquered and/or rebellious armies were sold into captivity.[72] Zoroastrianism, the de facto religion of the empire, explicitly forbids slavery,[73] and the kings of Achaemenid Persia, especially the founder Cyrus the Great, followed this ban to varying degrees, as evidenced by the freeing of the Jews at Babylon, and the construction of Persepolis by paid workers.

The vexilloid of the Achaemenid Empire was a gold falcon on a field of crimson.[74][75]

Military

Despite its humble origins in Persis, the empire reached an enormous size under the leadership of Cyrus the Great. Cyrus created a multi-state empire where he allowed regional rulers, called the 'satrap' to rule as his proxy over a certain designated area of his empire called the satrapy. The basic rule of governance was based upon loyalty and obedience of each satrapy to the central power, or the king, and compliance with tax laws.[29] Due to the ethnocultural diversity of the subject nations under the rule of Persia, its enormous geographic size, and the constant struggle for power by regional competitors,[14] the creation of a professional army was necessary for both maintenance of the peace, and also to enforce the authority of the king in cases of rebellion and foreign threat.[19][67] Cyrus managed to create a strong land army, using it to advance in his campaigns in Babylonia, Lydia, and Asia Minor, which after his death was used by his son Cambyses II, in Egypt against Psamtik III. Cyrus would die battling a local Iranian insurgency in the empire, before he could have a chance to develop a naval force.[76] That task however would fall to Darius the Great, who would officially give Persians their own royal navy to allow them to engage their enemies on multiple seas of this vast empire, from the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea, to the Persian Gulf, Ionian Sea and the Mediterranean Sea.

Navy

Since its foundation by Cyrus, the Persian empire had been primarily a land empire with a strong army, but void of any actual naval forces. By the 5th century BC, this was to change, as the empire came across Greek, and Egyptian forces, each with their own maritime traditions and capabilities. Darius the Great (Darius I) is to be credited as the first Achaemenid king to invest in a Persian fleet.[77] Even by then no true "imperial navy" had existed either in Greece or Egypt. Persia would become the first empire, under Darius, to inaugurate and deploy the first regular imperial navy.[77] Despite this achievement, the personnel for the imperial navy would not come from Iran, but were often Phoenicians (mostly from Sidon), Egyptians, Cypriots, and Greeks chosen by Darius the Great to operate the empire's combat vessels.[77]

At first the ships were built in Sidon by the Phoenicians; the first Achaemenid ships measured about 40 meters in length and 6 meters in width, able to transport up to 300 Persian troops at any one trip. Despite origin of the technique of the arsenal and ship construction in Sidon, soon other states of the empire were constructing their own ships each incorporating slight local preferences. The ships eventually found their way to the Persian Gulf.[77] Persian naval forces laid the foundation for a strong Persian maritime presence in the Persian Gulf. Persians were not only stationed on islands in the Persian Gulf, but also had ships often of 100 to 200 capacity patrolling the empire's various rivers including the Shatt-al-Arab, Tigris and Nile in the west, as well as the Indus.[77]

The Achaemenid navy established bases located along the Shatt-al-Arab, Bahrain, Oman, and Yemen. The Persian fleet was not only used for peace-keeping purposes along the Shatt al-Arab but also opened the door to trade with India via the Persian Gulf.[77] Darius's navy was in many ways a world power at the time, but it would be Artaxerxes II who in the summer of 397 BC would build a formidable navy, as part of a rearmament which would lead to his decisive victory at Knidos in 394 BC, reestablishing Achaemenid power in Ionia. Artaxerxes II would also utilize his navy to later on quell a rebellion in Egypt.[78]

The construction material of choice was wood, but some armored Achaemenid ships had metallic blades on the front, often meant to slice enemy ships using the ship's momentum. Naval ships were also equipped with hooks on the side to grab enemy ships, or to negotiate their position. The ships were propelled by sails or manpower. The ships the Persians created were unique. As far as maritime engagement, the ships were equipped with two mangonels that would launch projectiles such as stones, or flammable substances.[77]

Xenophon describes his eye-witness account of a massive military bridge created by joining 37 Persian ships across the Tigris river. The Persians utilized each boat's buoyancy, in order to support a connected bridge above which supply could be transferred.[77] Herodotus also gives many accounts of Persians utilizing ships to build bridges.[79][80] Darius the Great, in an attempt to subdue the Scythian horsemen north of the Black sea, crossed over at the Bosphorus, using an enormous bridge made by connecting Achaemenid boats, then marched up to the Danube, crossing it by means of a second boat bridge.[81] The bridge over the Bosphorus essentially connected the nearest tip of Asia to Europe, encompasing at least some 1000 meters of open water if not more. Herodotus describes the spectacle, and calls it the "bridge of Darius":[82]

- "Strait called Bosphorus, across which the bridge of Darius had been thrown is hundred and twenty furlongs in length, reaching from the Euxine, to the Propontis. The Propontis is five hundred furlongs across, and fourteen hundred long. Its waters flow into the Hellespont, the length of which is four hundred furlongs ..."

Years later, a similar boat bridge would be constructed by Xerxes the Great (Xerxes I), in his invasion of Greece. Although the Persians failed to capture the Greek city states completely, the tradition of maritime involvement was carried down by the Persian kings, most notably Artaxerxes II. Years later, when Alexander invaded Persia and during his advancement into India, he took a page from the Persian art of war, by having Hephaestion and Perdiccas construct a similar boat-bridge at the Indus river, in India in spring of 327 BC[83]

Culture

Herodotus, in his mid-5th century BCE account of Persian residents of the Pontus, reports that Persian youths, from their fifth year to their twentieth year, were instructed in three things – to ride a horse, to draw a bow, and to speak the Truth.[84]

He further notes that:[84]

- the most disgraceful thing in the world [the Persians] think, is to tell a lie; the next worst, to owe a debt: because, among other reasons, the debtor is obliged to tell lies.

In Achaemenid Persia, the lie, druj, is considered to be a cardinal sin, and it was punishable by death in some extreme cases. Tablets discovered by archaeologists in the 1930s[85] at the site of Persepolis give us adequate evidence about the love and veneration for the culture of truth during the Achaemenian period. These tablets contain the names of ordinary Persians, mainly traders and warehouse-keepers.[86] According to Professor Stanley Insler of Yale University, as many as 72 names of officials and petty clerks found on these tablets contain the word truth.[87] Thus, says Insler, we have Artapana, protector of truth, Artakama, lover of truth, Artamanah, truth-minded, Artafarnah, possessing splendour of truth, Artazusta, delighting in truth, Artastuna, pillar of truth, Artafrida, prospering the truth and Artahunara, having nobility of truth. It was Darius the Great who laid down the ordinance of good regulations during his reign. King Darius' testimony about his constant battle against the lie is found in cuneiform inscriptions. Carved high up in the Behistun mountain on the road to Kermanshah, Darius the Great (Darius I) testifies:[88]

- I was not a lie-follower, I was not a doer of wrong ... According to righteousness I conducted myself. Neither to the weak or to the powerful did I do wrong. The man who cooperated with my house, him I rewarded well; who so did injury, him I punished well.

Darius had his hands full dealing with large-scale rebellion which broke out throughout the empire. After fighting successfully with nine traitors in a year, Darius records his battles against them for posterity and tells us how it was the lie that made them rebel against the empire. At Behistun, Darius says:

- I smote them and took prisoner nine kings. One was Gaumata by name, a Magian; he lied; thus he said: I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus ... One, Acina by name, an Elamite; he lied; thus he said: I am king in Elam ... One, Nidintu-Bel by name, a Babylonian; he lied; thus he said: I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus.

King Darius then tells us,

- The Lie made them rebellious, so that these men deceived the people.[89]

Then advice to his son Xerxes, who is to succeed him as the great king:

- Thou who shalt be king hereafter, protect yourself vigorously from the Lie; the man who shall be a lie-follower, him do thou punish well, if thus thou shall think. May my country be secure!

Languages

During the reign of Cyrus and Darius, and as long as the seat of government was still at Susa in Elam, the language of the chancellory was Elamite. This is primarily attested in the Persepolis fortification and treasury tablets that reveal details of the day-to-day functioning of the empire.[86] In the grand rock-face inscriptions of the kings, the Elamite texts are always accompanied by Akkadian and Old Persian inscriptions, and it appears that in these cases, the Elamite texts are translations of the Old Persian ones. It is then likely that although Elamite was used by the capital government in Susa, it was not a standardized language of government everywhere in the empire. The use of Elamite is not attested after 458 BC.

Following the conquest of Mesopotamia, the Aramaic language (as used in that territory) was adopted as a "vehicle for written communication between the different regions of the vast empire with its different peoples and languages. The use of a single official language, which modern scholarship has dubbed Official Aramaic or Imperial Aramaic, can be assumed to have greatly contributed to the astonishing success of the Achaemenids in holding their far-flung empire together for as long as they did."[90] In 1955, Richard Frye questioned the classification of Imperial Aramaic as an "official language", noting that no surviving edict expressly and unambiguously accorded that status to any particular language.[91] Frye reclassifies Imperial Aramaic as the "lingua franca" of the Achaemenid territories, suggesting then that the Achaemenid-era use of Aramaic was more pervasive than generally thought. Many centuries after the fall of the empire, Aramaic script and – as ideograms – Aramaic vocabulary would survive as the essential characteristics of the Pahlavi writing system.[92]

Although Old Persian also appears on some seals and art objects, that language is attested primarily in the Achaemenid inscriptions of Western Iran, suggesting then that Old Persian was the common language of that region. However, by the reign of Artaxerxes II, the grammar and orthography of the inscriptions was so "far from perfect"[93] that it has been suggested that the scribes who composed those texts had already largely forgotten the language, and had to rely on older inscriptions, which they to a great extent reproduced verbatim.[94]

Customs

Herodotus mentions that the Persians were invited to great birthday feasts (Herodotus, Histories 8), which would be followed by many desserts, a treat which they reproached the Greeks for omitting from their meals. He also observed that the Persians drank wine in large quantities and used it even for counsel, deliberating on important affairs when drunk, and deciding the next day, when sober, whether to act on the decision or set it aside.

Religion

It was during the Achaemenid period that Zoroastrianism reached South-Western Iran, where it came to be accepted by the rulers and through them became a defining element of Persian culture. The religion was not only accompanied by a formalization of the concepts and divinities of the traditional Iranian pantheon but also introduced several novel ideas, including that of free will.[95][96]

Under the patronage of the Achaemenid kings, and by the 5th century BCE as the de facto religion of the state, Zoroastrianism reached all corners of the empire. The Bible claims that Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to return to their homeland after decades of captivity by the Assyrian and Babylonian empires.

During the reign of Artaxerxes I and Darius II, Herodotus wrote "[the Perses] have no images of the gods, no temples nor altars, and consider the use of them a sign of folly. This comes, I think, from their not believing the gods to have the same nature with men, as the Greeks imagine." He claims the Persians offer sacrifice to: "the sun and moon, to the earth, to fire, to water, and to the winds. These are the only gods whose worship has come down to them from ancient times. At a later period they began the worship of Urania, which they borrowed from the Arabians and Assyrians. Mylitta is the name by which the Assyrians know this goddess, to whom the Persians referred as Anahita." (The original name here is Mithra, which has since been explained to be a confusion of Anahita with Mithra, understandable since they were commonly worshipped together in one temple).

From the Babylonian scholar-priest Berosus, who—although writing over seventy years after the reign of Artaxerxes II Mnemon—records that the emperor had been the first to make cult statues of divinities and have them placed in temples in many of the major cities of the empire (Berosus, III.65). Berosus also substantiates Herodotus when he says the Persians knew of no images of gods until Artaxerxes II erected those images. On the means of sacrifice, Herodotus adds "they raise no altar, light no fire, pour no libations." This sentence has been interpreted to identify a critical (but later) accretion to Zoroastrianism. An altar with a wood-burning fire and the Yasna service at which libations are poured are all clearly identifiable with modern Zoroastrianism, but apparently, were practices that had not yet developed in the mid-5th century. Boyce also assigns that development to the reign of Artaxerxes II (4th century BC), as an orthodox response to the innovation of the shrine cults.

Herodotus also observed that "no prayer or offering can be made without a magus present" but this should not be confused with what is today understood by the term magus, that is a magupat (modern Persian: mobed), a Zoroastrian priest. Nor does Herodotus' description of the term as one of the tribes or castes of the Medes necessarily imply that these magi were Medians. They simply were a hereditary priesthood to be found all over Western Iran and although (originally) not associated with any one specific religion, they were traditionally responsible for all ritual and religious services. Although the unequivocal identification of the magus with Zoroastrianism came later (Sassanid era, 3rd–7th century AD), it is from Herodotus' magus of the mid-5th century that Zoroastrianism was subject to doctrinal modifications that are today considered to be revocations of the original teachings of the prophet. Also, many of the ritual practices described in the Avesta's Vendidad (such as exposure of the dead) were already practiced by the magu of Herodotus ' time.

Art and architecture

Achaemenid architecture refers to the architectural achievements of the Achaemenid Persians manifesting in construction of spectacular cities utilized for governance and habitation, temples made for worship and social gatherings (such as Zoroastrian temples), and mausoleums erected in honor of fallen kings (such as the burial tomb of Cyrus the Great). The quintessential feature of Persian architecture was its eclectic nature with elements of Median, Assyrian, and Asiatic Greek all incorporated, yet maintaining a unique Persian identity seen in the finished products.[97]

Achaemenid art refers to the artistic achievements of the Achaemenid Persians manifesting in construction of complicated frieze reliefs, crafting of precious metals (such as the Oxus Treasure), decoration of palaces, glazed brick masonry, fine craftsmanship (masonry, carpentry, etc.), and gardening, and outdoor decoration. It is critical to understand that although Persians borrowed techniques from all corners of their empire, it was not simply a combination of styles, but a synthesis of a new unique Persian style.[98] Cyrus the Great in fact had an extensive ancient Iranian heritage behind him; the rich Achaemenid gold work, which inscriptions suggest may have been a specialty of the Medes, was for instance in the tradition of the delicate metalwork found in Iron Age II times at Hasanlu and still earlier at Marlik.

One of the most amazing examples of both Achaemenid architecture and art is the grand palace of Persepolis, and its detailed workmanship, coupled with its grand scale. In describing the construction of his palace at Susa, Darius the Great records that:

Yaka timber was brought from Gandara and from Carmania. The gold was brought from Sardis and from Bactria ... the precious stone lapis-lazuli and carnelian ... was brought from Sogdiana. The turquoise from Chorasmia, the silver and ebony from Egypt, the ornamentation from Ionia, the ivory from Ethiopia and from Sindh and from Arachosia. The stone-cutters who wrought the stone, those were Ionians and Sardians. The goldsmiths were Medes and Egyptians. The men who wrought the wood, those were Sardians and Egyptians. The men who wrought the baked brick, those were Babylonians. The men who adorned the wall, those were Medes and Egyptians.

This was imperial art on a scale the world had not seen before. Materials and artists were drawn from all corners of the empire, and thus tastes, styles, and motifs became mixed together in an eclectic art and architecture that in itself mirrored the Persian empire.

Legacy

The Achaemenid Empire left a lasting impression on the heritage and the cultural identity of Asia and the Middle East, as well as influencing the development and structure of future empires. In fact the Greeks and later on the Romans copied the best features of the Persian method of governing the empire, and vicariously adopted them.[99]

Georg W. F. Hegel in his work The Philosophy of History introduces the Persian Empire as the "first empire that passed away" and its people as the "first historical people" in history. According to his account;[100]

- The Persian Empire is an empire in the modern sense – like that which existed in Germany, and the great imperial realm under the sway of Napoleon; for we find it consisting of a number of states, which are indeed dependant, but which have retained their own individuality, their manners, and laws. The general enactments, binding upon all, did not infringe upon their political and social idiosyncrasies, but even protected and maintained them; so that each of the nations that constitute the whole, had its own form of constitution. As light illuminates everything – imparting to each object a peculiar vitality – so the Persian Empire extends over a multitude of nations, and leaves to each one its particular character. Some have even kings of their own; each one its distinct language, arms, way of life and customs. All this diversity coexists harmoniously under the impartial dominion of Light ... a combination of peoples – leaving each of them free. Thereby, a stop is put to that barbarism and ferocity with which the nations had been wont to carry on their destructive feuds.

The famous American orientalist, Professor Arthur Upham Pope (1881–1969) said:[101] "The western world has a vast unpaid debt to the Persian Civilization!"

Will Durant, the American historian and philosopher, during one his speeches, "Persia in the History of Civilization", as an address before the Iran-America Society in Tehran on 21 April 1948, stated:[102]

- For thousands of years Persians have been creating beauty. Sixteen centuries before Christ there went from these regions or near it ... You have been here a kind of watershed of civilization, pouring your blood and thought and art and religion eastward and westward into the world ... I need not rehearse for you again the achievements of your Achaemenid period. Then for the first time in known history an empire almost as extensive as the United States received an orderly government, a competence of administration, a web of swift communications, a security of movement by men and goods on majestic roads, equaled before our time only by the zenith of Imperial Rome.

Achaemenid kings and rulers

Unattested

- The epigraphic evidence for these rulers cannot be confirmed and are often considered to have been invented by Darius I

- Ariaramnes of Persia, son of Teispes and co-ruler with Cyrus I

- Arsames of Persia, son of Ariaramnes and co-ruler with Cambyses I

Attested

| King | Reign (BC) | Consort(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teispes of Anshan | 7th century | son of Achaemenes, King of Anshan | |

| Cyrus I | Late 7th / early 6th century | son of Teispes, King of Anshan | |

| Cambyses I of Anshan | Early 6th Century | Mandana of Media | son of Cyrus I, King of Anshan |

| Cyrus II the Great | c. 550–530 | Cassandane of Persia | son of Cambyses I and Mandana – conquered Media 550 BC King of Media, Babylonia, Lydia, Persia, Anshan, and Sumer. Created the Achaemenid Persian Empire. |

| King | Reign (BC) | Consort(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cambyses II | 529–522 | son of Cyrus the Great and Cassandane. Conquered dynasty of Egypt. | |

| Bardiya (Smerdis) | 522 | Phaedymia | Son of Cyrus the Great. (Imposter Gaumata acted in his place) |

| Darius I the Great | 521–486 | Atossa Artystone Parmys Phratagune | son-in-law of Cyrus the Great, son of Hystaspes, grandson of Arsames Armies defeated at Battle of Marathon in Greece. |

| Xerxes I the Great | 485–465 | Amestris | son of Darius I and Atossa Victorious at Battle of Thermopylae Defeated at Battle of Salamis |

| Artaxerxes I Longimanus | 465–424 | Damaspia Cosmartidene Alogyne Andia | son of Xerxes I and Amestris |

| Xerxes II | 424 | son of Artaxerxes I and Damaspia | |

| Sogdianus | 424–423 | Son of Artaxerxes I and Alogyne; half-brother and rival of Xerxes II | |

| Darius II of Persia | 423–405 | Parysatis | Son of Artaxerxes I and Cosmartidene; half-brother and rival of Xerxes II |

| Artaxerxes II Mnemon | 404–359 | Stateira | son of Darius II (see also Xenophon) |

Early in the reign of Artaxerxes II, in 399 BCE, the Persians lose control over Egypt. They regained control 57 years later – in 342 BCE – when Artaxerxes III conquered Egypt.

| King | Reign (BC) | Consort(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artaxerxes III Ochus | 358–338 | son of Artaxerxes II and Stateira | |

| Artaxerxes IV Arses | 338–336 | son of Artaxerxes III and Atossa | |

| Darius III | 336–330 | Stateira I | great-grandson of Darius II defeated by Alexander the Great |

Gallery

-

Panorama of Persepolis Ruins

-

Ruins of Throne Hall

-

Persepolis gifts

-

Apadana Hall, Persian and Median soldiers at Persepolis

-

Nowruz Zoroastrian

-

Lateral view of tomb of Cambyses I, Pasargadae, Iran

See also

Notes

- ↑ Yarshater, Ehsan (1993). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 482. ISBN 978-0-521-20092-9.

Of the four residences of the Achaemenids named by Herodotus — Ecbatana, Pasargadae or Persepolis, Susa and Babylon — the last [situated in Iraq] was maintained as their most important capital, the fixed winter quarters, the central office of bureaucracy, exchanged only in the heat of summer for some cool spot in the highlands. Under the Seleucids and the Parthians the site of the Mesopotamian capital moved a little to the north on the Tigris — to Seleucia and Ctesiphon. It is indeed symbolic that these new foundations were built from the bricks of ancient Babylon, just as later Baghdad, a little further upstream, was built out of the ruins of the Sassanian double city of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.

- ↑ Harald Kittel, Juliane House, Brigitte Schultze; Juliane House; Brigitte Schultze (2007). Traduction: encyclopédie internationale de la recherche sur la traduction. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1194–5. ISBN 978-3-11-017145-7.

- ↑ Greek and Iranian, E. Tucker, A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity, ed. Anastasios-Phoivos Christidēs, Maria Arapopoulou, Maria Chritē, (Cambridge University Press, 2001), 780.

- ↑ Boiy, T. (2004). Late Achaemenid and Hellenistic Babylon. Peeters Publishers. p. 101. ISBN 978-90-429-1449-0.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Yarshater (1996, p. 47)

- ↑ Security and Territoriality in the Persian Gulf: A Maritime Political Geography by Pirouz Mojtahed-Zadeh, page 119

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 http://www.livius.org/maa-mam/maka/maka.html

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Behistun Inscription

- ↑ Josef Wiesehöfer, Ancient Persia, (I.B. Tauris Ltd, 2007), 119.

- ↑ Unicode: 𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿 http://titus.uni-frankfurt.de/texte/etcs/iran/airan/apers/aperslex.htm Switch to word Index, search 'Pārsa' under Oldpersian-trl.

- ↑ http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/eieol/opeol-MG-X.html

- ↑ http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~iranian/OldPersian/OPers5_End.pdf

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Sampson, Gareth C. (2008). The Defeat of Rome: Crassus, Carrhae and the Invasion of the East. Pen & Sword Books Limited. p. 33. ISBN 9781844156764.

Cyrus the Great, founder of the First Persian Empire (c. 550–330 BCE).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 David Sacks, Oswyn Murray, Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. pp. 256 (at the right portion of the page). ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

- ↑ http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/eieol/opeol-MG-X.html Macdonell and Keith, Vedic Index. This is based on the evidence of an Assyrian inscription of 844 BCE referring to the Persians as Paršu, and the Behistun Inscription of Darius I referring to Parsa (Pārsa) as the area of the Persians. Radhakumud Mookerji (1988). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times (p. 23). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 81-208-0405-8.

- ↑ Aedeen Cremin (2007). Archaeologica: The World's Most Significant Sites and Cultural Treasures. Global Book Publishing Pty Ltd. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-7112-2822-1.

- ↑ While estimates for the Achaemenid Empire range from 10–80+ million, most prefer 50 million. Prevas (2009, p. 14) estimates 10 million. Strauss (2004, p. 37) estimates about 20 million. Ward (2009, p. 16) estimates at 20 million. Scheidel (2009, p. 99) estimates 35 million. Daniel (2001, p. 41) estimates at 50 million. Meyer and Andreades (2004, p. 58) estimates to 50 million. Jones (2004, p. 8) estimates over 50 million. Richard (2008, p. 34) estimates nearly 70 million. Hanson (2001, p. 32) estimates almost 75 million. Cowley (1999 and 2001, p. 17) estimates possibly 80 million.

- ↑ "Largest empire by percentage of world population". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty)

- ↑ Ulrich Wilcken (1967). Alexander the Great. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-393-00381-9.

- ↑ Margaret Christina Miller (2004). Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century BCE: A Study in Cultural Receptivity. Cambridge University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-521-60758-2.

- ↑ Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri VII, 11

- ↑ Plutarch, Alexander, 45

- ↑ Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, Sarah Stewart (2005). Birth of the Persian Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-84511-062-8.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Jamie Stokes (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Volume 1. Infobase Publishing. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-8160-7158-6.

- ↑ Mallory, J.P. (1989), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth, London: Thames & Hudson.

- ↑ Schlerath p. 36, no. 9. See also Iranica in the Achaemenid Period p. 17.

- ↑ Simon Anglim; Simon Anglim; Phyllis Jestice; Scott Rusch; John Serrati (2002). Fighting techniques of the ancient world 3,000 BCE – 500 CE: equipment, combat skills, and tactics. Macmillan. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-312-30932-9.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Palmira Johnson Brummett, Robert R. Edgar, Neil J. Hackett; Robert R. Edgar; Neil J. Hackett (2003). Civilization past & present, Volume 1. Longman. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-321-09097-3.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Charles Gates (2003). Ancient cities: the archaeology of urban life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Psychology Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-415-12182-8.

- ↑ David Sacks, Oswyn Murray, Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. pp. 256 (at the bottom left portion). ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

- ↑ Dandamayev

- ↑ Haydn Middleton (2 October 2002). Ancient Greek War and Weapons. Haydn Middleton. pp. 12–3. ISBN 978-1-4034-0134-2.

- ↑ Lawrence Heyworth Mills (1906). Zarathustra, Philo, the Achaemenids and Israel. Open Court. p. 467.

- ↑ "Isaiah 45:1–7 (Passage)". Bible gateway (New International Version). 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Maria Brosius (2006). The Persians: an introduction. Taylor & Francis. pp. 13 (at the bottom of the page). ISBN 978-0-415-32089-4.

- ↑ Herodotus – Volume 1, Book II

- ↑ Augustus William Ahl (1922). Outline of Persian history based on cuneiform inscriptions. Lemcke & Buechner. p. 56.

- ↑ "Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Concise.britannica.com. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ↑ Jona Lendering. "Nidintu-Bêl / Nebuchadnezzar III". Livius.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ↑ Herodotus (1897). Herodotus: the text of Canon Rawlinson's translation, with the notes abridged, Volume 1. C. Scribner's. p. 278.

- ↑ Herodotus. The Histories Book 3.80–83.

- ↑ Pierre Briant, Amélie Kuhrt; Amélie Kuhrt (26 July 2010). Alexander the Great and His Empire: A Short Introduction. Princeton University Press. pp. 183–5. ISBN 978-0-691-14194-7.

- ↑ Ramirez-Faria, Carlos (2007). Concise Encyclopeida Of World History. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 6. ISBN 81-269-0775-4. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ↑ Kuhrt, Amélie (2007). The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 1-134-07634-7. Retrieved October 7, 2012.. O'Brien, Patrick (2002). Concise Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-19-521921-X. Retrieved October 7, 2012.. Curtis, John E.; Tallis, Nigel (2005). Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia. University of California Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-520-24731-0.. Facts On File, Incorporated (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Infobase Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 1-4381-2676-X. Retrieved October 7, 2012.. Parker, Grant (2008). The Making of Roman India. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-521-85834-8. Retrieved October 7, 2012.. Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. p. 157. ISBN 0-520-24225-4. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ↑ Willis Mason West (1904). The ancient world from the earliest times to 800 CE. Allyn and Bacon. p. 137.

The Athenian support was particularly troubling to Darius since he had come to their aid during their conflict with Sparta

- ↑ Hoschander, Jacob. "The Book of Esther in the Light of History: Chapter IV", The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jul., 1919), pp. 87–88

- ↑ Chr. Walker, "Achaemenid Chronology and the Babylonian Sources," in: John Curtis (ed.), Mesopotamia and Iran in the Persian Period: Conquest and Imperialism, 539–331 B.C.E. (London 1997), page 22.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 ((grk.) Lucius Flavius Arrianus) (en.) Arrian – (trans.) Charles Dexter Cleveland (1861). A compendium of classical literature: comprising choice extracts translated from Greek and Roman writers, with biographical sketches. Biddle. p. 313.

- ↑ Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson (1906). Persia past and present. The Macmillan Company. p. 278.

- ↑ Ralph Griffiths, George Edward Griffiths; George Edward Griffiths (1816). The Monthly review. 1816. p. 509.

- ↑ Theodore Ayrault Dodge (1890). Alexander: a history of the origin and growth of the art of war from the earliest times to the battle of Ipsus, B.C. 301, with a detailed account of the campaigns of the great Macedonian. Houghton, Mifflin & Co. p. 438.

- ↑ Sir William Smith (1887). A smaller history of Greece: from the earliest times to the Roman conquest. Harper & Brothers. p. 196.

- ↑ Freeman 1999: p. 188

- ↑ A.T. Olmstead, History of the Persian Empire, "Overtaxation and Its Results,' University of Chicago Press, ç1948, p.289-301

- ↑ The Penguin Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations, ed. Arthur Cotterell, Penguin Books Ltd., London, ç1980, p.154

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage, Simon and Schuster, Inc., New York, ç1935, p.363

- ↑ Charles Robinson Jr., Ancient History, 2nd ed., MacMillan Company, New York, ç1967, p.328, 338

- ↑ Charles Robinson Jr., Ancient History, 2nd ed., MacMillan Company, New York, ç1967, p.391, 347

- ↑ Charles Robinson Jr., Ancient History, 2nd ed., MacMillan Company, New York, ç1967, p.351

- ↑ Peter Levi, The Greek World, Equinox Book-Andromeda, Oxford Ltd., ç1990, p.182

- ↑ Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage, Simon and Schuster, Inc., New York, ç1935, p.382

- ↑ R.L. Fox, The Search For Alexander, Little Brown and Co., Boston, ç1980, p.121-122

- ↑ Ashrafian, Hutan. (2011). "Limb gigantism, neurofibromatosis and royal heredity in the Ancient World 2500 years ago: Achaemenids and Parthians". J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 64 (4): 557. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2010.08.025. PMID 20832372.

- ↑ Collon, Dominique, First Impressions, Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East: p.90, British Museum Press, 1987, 2005. ISBN 0-7141-1136-8

- ↑ Engineering an Empire – The Persians. Broadcast of The History Channel, narrated by Peter Weller

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Pierre Briant (2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-57506-120-7.

- ↑ Herodotus, Herodotus, trans. A.D. Godley, vol. 4, book 8, verse 98, pp. 96–97 (1924).

- ↑ Persepolis Recreated, NEJ International Pictures; 1st edition (2005) ISBN 978-964-06-4525-3 ASIN B000J5N46S, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nCwxJsk14e4

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 "History Of Iran (Persia)". Historyworld.net. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ "Darius I (Darius the Great), King of Persia (from 521 BC)". 1902encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ M. Dandamayev, "Foreign Slaves on the Estates of the Achaemenid Kings and their Nobles," in Trudy dvadtsat' pyatogo mezhdunarodnogo kongressa vostokovedov II, Moscow, 1963, pp. 151–52

- ↑ "Volume 2". Zarathushtra.com. 11 February 2005. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ↑ "Vexilloid of the Achaemenid Empire". Archived from the original on 24 October 2009.

- ↑ "Flags of Persian History". Archived from the original on 24 October 2009.

- ↑ A history of Greece, Volume 2, By Connop Thirlwall, Longmans, 1836, p. 174

- ↑ Ehsan Yar-Shater (1982). Encyclopaedia Iranica, Volume 4, Issues 5–8. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ↑ John Manuel Cook (1983). The Persian Empire. Schocken Books.

- ↑ E. V. Cernenko, Angus McBride, M. V. Gorelik (1983-03-24). The Scythians, 700-300 BC. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-478-9.

- ↑ Herodotus (Translation by George Rawlinson, Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, Sir John Gardner Wilkinson); George Rawlinson; Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson; Sir John Gardner Wilkinson (1859). The History of Herodotus: a new English version, Volume 3. John Murray. pp. 77 (Chp. 86).

- ↑ Waldemar Heckel (2006). Who's who in the age of Alexander the Great: prosopography of Alexander's empire. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-4051-1210-9.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Herodotus (2009) [publication date]. The Histories. Translated by George Rawlinson. Digireads.Com. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-1-4209-3305-5.

- ↑ Garrison, Mark B. and Root, Margaret C. (2001). Seals on the Persepolis Fortification Tablets, Volume 1. Images of Heroic Encounter (OIP 117). Chicago: Online Oriental Institute Publications. Archived from the original on 5 January 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Dandamayev, Muhammad (2002). "Persepolis Elamite Tablets". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Insler, Stanley (1975). "The Love of Truth in Ancient Iran". Retrieved 9 January 2007. In Insler, Stanley; Duchesne-Guillemin, J. (ed.) (1975). The Gāthās of Zarathustra (Acta Iranica 8). Liege: Brill.

- ↑ Brian Carr; Brian Carr; Indira Mahalingam (1997). Companino Encyclopedia of Asian philosophy. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-03535-4.

- ↑ "Darius, Behishtan (DB), Column 1". From Kent, Roland G. (1953). Old Persian: Grammar, texts, lexicon. New Haven: American Oriental Society.

- ↑ Shaked, Saul (1987). "Aramaic". Encyclopedia Iranica 2. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 250–261. p. 251

- ↑ Frye, Richard N.; Driver, G. R. (1955). "Review of G. R. Driver's "Aramaic Documents of the Fifth Century B. C."". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies (Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 18, No. 3/4) 18 (3/4): 456–461. doi:10.2307/2718444. JSTOR 2718444. p. 457.

- ↑ Geiger, Wilhelm & Ernst Kuhn (2002). Grundriss der iranischen Philologie: Band I. Abteilung 1. Boston: Adamant. pp. 249ff.

- ↑ Ware, James R. and Kent, Roland G. (1924). "The Old Persian Cuneiform Inscriptions of Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association (Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 55) 55: 52–61. doi:10.2307/283007. JSTOR 283007. p. 53

- ↑ Gershevitch, Ilya (1964). "Zoroaster's own contribution". Journal of Near Eastern Studies 23 (1): 12–38. doi:10.1086/371754. p. 20.

- ↑ A. V. Williams Jackson (2003). Zoroastrian Studies: The Iranian Religion and Various Monographs (1928). Kessinger Publishing. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-7661-6655-4.

- ↑ Virginia Schomp (2009). The Ancient Persians. Marshall Cavendish. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7614-4218-9.

- ↑ Charles Henry Caffin (1917). How to study architecture. Dodd, Mead and Company. p. 80.

- ↑ Edward Lipiński, Karel van Lerberghe, Antoon Schoors; Karel Van Lerberghe; Antoon Schoors (1995). Immigration and emigration within the ancient Near East. Peeters Publishers. p. 119. ISBN 978-90-6831-727-5.

- ↑ "Mastering World History" by Philip L. Groisser, New York, 1970, p.17

- ↑ George W. F. Hegel (2007-06-01). The Philosophy of History. ISBN 9781602064386.

- ↑ "The History of the Persian Civilization" by Arthur Pope, P.11

- ↑ Durant, Will. "Persia in the History of Civilization" (PDF). Addressing 'Iran-America Society. Mazda Publishers, Inc.

References

- Briant, Pierre. "Alexander". Encyclopaedia Iranica. vol. 3. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- A. Sh. Shahbazi. ARIARAMNEIA. vol. 2. Encyclopaedia Iranica (Routledge & Kegan Paul).

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. "Achaemenid dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica. vol. 3. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Schlerath, Bernfried (1973). Die Indogermanen. Inst. f. Vergl. Sprachwiss. ISBN 3-85124-516-4.

- Tavernier, Jan (2007). Iranica in the Achaemenid Period (ca. 550-330 B.C.): Linguistic Study of Old Iranian Proper Names and Loanwords, Attested in Non-Iranian Texts. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 90-429-1833-0.

- Stronach, David "Darius at Pasargadae: A Neglected Source for the History of Early Persia," Topoi

- Stronach, David "Anshan and Parsa: Early Achaemenid History, Art and Architecture on the Iranian Plateau". In: John Curtis, ed., Mesopotamia and Iran in the Persian Period: Conquest and Imperialism 539–331, 35–53. London: British Museum Press 1997.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef. "History in pre-Islamic period". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

Further reading

- Wiesehöfer, Josef; Azizeh Azodi (translator) (2001). Ancient Persia. London, New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-675-1. There have been a number of editions since 1996.

- Curtis, John E.; Nigel Tallis (editors) (2005). Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24731-0. A collection of articles by different authors.

- Pierre Briant (January 2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: a history of the Persian Empire. ISBN 978-1-57506-031-6.

- The Greco-Persian Wars, Peter Green

- Philip Souza (2003-01-25). The Greek and Persian Wars 499-386 BC. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-358-3.

- The Heritage of Persia, Richard N. Frye

- History of the Persian Empire, A.T. Olmstead

- The Persian Empire, Lindsay Allen

- The Persian Empire, J.M. Cook

- Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West, Tom Holland

- Pictorial History of Iran: Ancient Persia Before Islam 15000 B.C.–625 A.D., Amini Sam

- Timelife Persians: Masters of the Empire (Lost Civilizations)

- M. A. Dandamaev (1989). A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 978-90-04-09172-6.

- Hallock, R., Persepolis Fortification Tablets

- Chopra, R.M., an article on "A Brief Review of Pre-Islamic Splendour of Iran", INDO-IRANICA, Vol.56 (1-4), 2003.

- Sideris, A. "Achaemenid Toreutics in the Greek Periphery", in Darabandi S. M. R. and A. Zournantzi (eds.), Ancient Greece and Ancient Iran. Cross-Cultural Encounters, Athens 2008, pp. 339–353.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Achaemenid Empire. |

| Look up Achaemenid Empire in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Persian History

- Livius.org on Achaemenids

- Swedish Contributions to the Archaeology of Iran Artikel i Fornvännen (2007) by Carl Nylander

- ČIŠPIŠ

- The Behistun Inscription

- Livius.org on Achaemenid Royal Inscriptions

- Achaemenid art on Iran Chamber Society (www.iranchamber.com)

- Persepolis Fortification Archive Project

- Photos of the tribute bearers from the 23 satrapies of the Achaemenid empire, from Persepolis

- medals and orders of the Persian empire

- Ancient Iran

- Dynasty Achaemenid

- Iran, The Forgotten Glory – Documentary Film About Ancient Iran (achaemenids & Sassanids)

- Achemenet The major electronic resource for the study of the history, literature and archaeology of the Persian Empire

- Persepolis Before Incursion (Virtual tour project)