Abortion in the United Kingdom

Abortion has been legal on a wide number of grounds in England and Wales and Scotland since the Abortion Act 1967 was passed. At the time, this legislation was considered one of the most liberal laws regarding abortion in Europe. However, the situation in Northern Ireland is somewhat different (see further).

Great Britain

Section 1(1) of the Abortion Act 1967

In England and Wales and Scotland, section 1(1) of the Abortion Act 1967 now reads:[1]

Subject to the provisions of this section, a person shall not be guilty of an offence under the law relating to abortion when a pregnancy is terminated by a registered medical practitioner if two registered medical practitioners are of the opinion, formed in good faith -

- (a) that the pregnancy has not exceeded its twenty-fourth week and that the continuance of the pregnancy would involve risk, greater than if the pregnancy were terminated, of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman or any existing children of her family; or

- (b) that the termination of the pregnancy is necessary to prevent grave permanent injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman; or

- (c) that the continuance of the pregnancy would involve risk to the life of the pregnant woman, greater than if the pregnancy were terminated

- (d) that there is a substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped.

Subsections (a) to (d) were substituted for the former subsections (a) and (b) by section 37(1) of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990.

See also www.homehealth-uk.com/medical/abortion.htm and news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/4350259.stm.

"The law relating to abortion"

In England and Wales, this means sections 58 and 59 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 and any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion.[2]

In Scotland, this means any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion.[2]

"Terminated by a registered medical practitioner"

See Royal College of Nursing of the UK v DHSS [1981] AC 800, [1981] 2 WLR 279, [1981] 1 All ER 545, [1981] Crim LR 322, HL.

Place where termination must be carried out

See sections 1(3) to (4).

The opinion of two registered medical practitioners

See section 1(4).

"Good faith"

See R v Smith (John Anthony James), 58 Cr App R 106, CA.

Determining the risk of injury in ss. (a) & (b)

See section 1(2)

"Risk, greater than if the pregnancy were terminated, of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman", s. 1(1)(a)

In R v British Broadcasting Corporation, ex parte ProLife Alliance, Lord Justice Laws said:

There is some evidence that many doctors maintain that the continuance of a pregnancy is always more dangerous to the physical welfare of a woman than having an abortion, a state of affairs which is said to allow a situation of de facto abortion on demand to prevail.[3]

England and Wales

Sections 58 and 59 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861

Section 58 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 provides:

- 58. Every woman, being with child, who, with intent to procure her own miscarriage, shall unlawfully administer to herself any poison or other noxious thing, or shall unlawfully use any instrument or other means whatsoever with the like intent, and whosoever, with intent to procure the miscarriage of any woman whether she be or be not with child, shall unlawfully administer to her or cause to be taken by her any poison or other noxious thing, or unlawfully use any instrument or other means whatsoever with the like intent, shall be guilty of felony, and being convicted thereof shall be liable . . . to be kept in penal servitude for life . . .[4]

Section 59 of that Act provides:

- 59. Whosoever shall unlawfully supply or procure any poison or other noxious thing, or any instrument or thing whatsoever, knowing that the same is intended to be unlawfully used or employed with intent to procure the miscarriage of any woman, whether she be or be not with child, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and being convicted thereof shall be liable . . . to be kept in penal servitude . . .[5]

"Unlawfully"

For the purposes of sections 58 and 59 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861, and any rule of law relating to the procurement of abortion, anything done with intent to procure a woman's miscarriage (or in the case of a woman carrying more than one foetus, her miscarriage of any foetus) is unlawfully done unless authorised by section 1 of the Abortion Act 1967 and, in the case of a woman carrying more than one foetus, anything done with intent to procure her miscarriage of any foetus is authorised by the said section 1 if the ground for termination of the pregnancy specified in subsection (1)(d) of the said section 1 applies in relation to any foetus and the thing is done for the purpose of procuring the miscarriage of that foetus, or any of the other ground for termination of the pregnancy specified in the said section 1 applies.[6]

"Felony" and "misdemeanor"

See the Criminal Law Act 1967.

Mode of trial

The offences under section 58 and 59 are indictable-only offences.

Sentence

An offence under section 58 is punishable with imprisonment for life or for any shorter term.[7]

An offence under section 59 is punishable with imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years.[8]

The Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929

Homicide

A death, of a person in being, which is caused by an unlawful attempt to procure an abortion is at least manslaughter.[9][10]

Broadcasting

As to the effect of section 6(1)(a) of the Broadcasting Act 1990 in relation to broadcasting pictures of an abortion, see R v British Broadcasting Corporation, ex parte ProLife Alliance [2003] UKHL 23, [2004] 1 AC 185, [2003] 2 WLR 1403, [2003] 2 All ER 977, [2003] UKHRR 758, [2003] HRLR 26, [2003] ACD 65, [2003] EMLR 23, reversing R v British Broadcasting Corporation, ex parte ProLife Alliance [2002] EWCA Civ 297, [2002] 3 WLR 1080, [2002] 2 All ER 756, CA. That section was repealed by the Communications Act 2003.

Northern Ireland

Devolution concerning health care

Health policy is part of the devolved powers transferred to the Northern Ireland Assembly (NIA) by the Northern Ireland Act of 1998 in the frame of the devolution in the United Kingdom.[11][12] Abortion Law in Northern Ireland falls within the scope of the Criminal Law in Northern Ireland. Criminal Justice and Policing powers were devolved to Northern Ireland in 2010.

Law concerning abortion

The Abortion Act 1967 does not extend to Northern Ireland.[13] The pieces of legislation governing abortion in Northern Ireland are sections 58 and 59 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 and sections 25 and 26 of the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1945 (which are derived from the corresponding provisions of the Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929).

An offence under section 58 is punishable with imprisonment for life or for any shorter term.[14]

Performing an abortion in Northern Ireland is an offence except in specific cases.[15] An offence under section 25(1) of the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1945 is, by the proviso to that section, not committed if the act which caused the death of a child was done in good faith for the purpose only of preserving the life of the mother. The word "unlawfully" in section 58 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861 imports the meaning expressed by the said proviso and thus section 58 must be read as if the words making it an offence to use the instrument with intent to procure a miscarriage were qualified by a similar proviso.[16] In other words a person who procures an abortion in good faith for the purpose of preserving the life of the mother is not guilty of an offence.[17] In Northern Ireland Health and Social Services Board v A and Others [1994] NIJB 1, MacDermott LJ said, at p 5, that he was "satisfied that the statutory phrase, 'for the purpose only of preserving the life of the mother' does not relate only to some life-threatening situation. Life in this context means that physical or mental health or well-being of the mother and the doctor’s act is lawful where the continuance of the pregnancy would adversely affect the mental or physical health of the mother. The adverse effect must however be a real and serious one and there will always be a question of fact and degree whether the perceived effect of non-termination is sufficiently grave to warrant terminating the unborn child." In Western Health and Social Services Board v CMB and the Official Solicitor (1995) unreported, Pringle J stated "the adverse effect must be permanent or long-term and cannot be short term … in most cases the adverse effect would need to be a probable risk of non-termination but a possible risk might be sufficient if the imminent death of the mother was a risk in question" [18] In Family Planning Association Of Northern Ireland v Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety (8 October 2004) - Nicholson LJ stated at paragraph 73 - ‘it is unlawful to procure a miscarriage where the foetus is abnormal but viable, unless there is a risk that the mother may die or is likely to suffer long-term harm, which is serious, to her physical or mental health.’[19] Sheil LJ stated at paragraph 9 - ‘termination of a pregnancy based solely on abnormality of the foetus is unlawful and cannot lawfully be carried out in this jurisdiction’ [20]

Thus, Northern Irish women have two solutions to have an abortion. They can either have a legal abortion via the NHS or in a private clinic in Northern Ireland (provided they meet the criteria of a serious and long term risk to mental or physical health that is probable and not possible),[21] or in all other circumstances travel in England, Scotland or Wales, and pay to terminate their pregnancy in a private clinic (provided they meet the legal criteria for accessing abortion services under the Abortion Act 1967).[22]

An actual case is the A & Ahor, R v Secretary of State for Health [2014].[23]

• Background: The claimant was an ordinarily resident in Northern Ireland that travelled to England in 2012 to abort in an independent clinic in Manchester. She considered unlawful the policy the Secretary of State adopted under the National Health Service Act. That meant that women who travel from Northern Ireland to England are not allowed to have a termination under the NHS, and also appointed that was incompatible with the claimant's Convention rights.

• Judge considerations: As for the policy, the judge shown that it was the Northern Ireland assembly that has decided not to legislate to provide that service.

Concerning the violation of the claimant's convention rights, the claimant argued that the policy mentioned above was incompatible with the Human Rights Act 1998. Particularly the article 14, which states that the enjoyment of the rights and freedom of the Human Rights Convention shall be secured without any discrimination on grounds of sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status.

Personal characteristic and status were the base of the claimant’s argumentation and were referred to the judgments of the European Court in Carson v UK (2010) 51 EHRR 13 case. In those, but related with state pensions, The Chamber held that, ordinary residence, like domicile and nationality, was to be seen as an aspect of personal status, that applied as a criteria for the differential treatment, violated the Article 14.

The claimant, as a citizen from the UK, had been treated differently concerning state funded abortions because unlike citizens that ordinarily reside in England, Scotland or Wales, had no option of returning to Northern Ireland to access an abortion covered by the state. Therefore, there was discrimination because there has been different treatment in analogous or relevantly similar situations.

But finally, any violation could be found because there is no suggestion in the case–law of the European Court of Human Rights that the State is required to fund abortion services and the claimant was entitled to and did access abortion services in England (at the independent clinic approved by the defendant), albeit not state funded.

Political and religious opinions on abortion

Democratic Unionist Party

The Health Minister, Jim Wells, has said that abortion is not justified in cases of rape. According to his words:

« that is a tragic and difficult situation but should the ultimate victim of that terrible act [rape]-which is the child- should he or she be punished for what has happened by having their life terminated? No”

Ulster Unionist Party

According to Mike Nesbitt

« we are waiting for the consultation and the justice minister has been liaising with the minister for health. My view is that we need a consultation and that a woman's voice should be stronger by a long way in that consultation”

Liberal Democrats

Following the Report to the United Nation on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women in July 2013, Jennifer Willot, member of the Party does agree that the UK are obliged to take into consideration the UN recommendation about the abortion law and services in Northern Ireland by November 2014.[26]

Progressive Unionist Party

Heading by Dawn Purvis, the party was the strong help to advocate for the Marie Stope International clinic and manage to emerge an independent abortion clinic.[27]

Sinn Féin

For the Northern Ireland's deputy First Minister, Martin McGuinness

«Sinn Fein is not in favor of abortion, and we resisted any attempt to bring the British 1967 Abortion Act to the North”

Social Democratic and Labour Party

Fearghal McKinney and his party have remained that they are fundamentally opposed to any extension of the 1967 act to Northern Ireland"[29]

Catholic

Considering the abortion, the Catholic party is base on the doctrine called the Doctrine of the Double Effect. This doctrine take into consideration if there is, or no, a direct intention to kill the fœtus : in this case it is not permissible ; or to achieve a good end : which become a permissible act (for save the mother life for example).[30]

Protestant

According to the Protestant leader of Precious Life (Belfast anti-abortion group)

«Women's health is not in danger. Women are not dying because they cannot get abortion”

.[31]

However, according to a recent Amnesty International's poll (October 2014), the population seems to agree to reform abortion's law in three particular cases: rape, incest, fatal fœtus abnormality.[32]

Feminist groups

For Polly Toynbee, a discrimination resides in this actual situation :

«We have to end the discrimination against women in Northern Ireland which as citizens of the UK, forbids them from having an abortion in their own home country”

.[33]

Situation in 2014

In July 2014, the Health Minister Jim Wells proposed an amendment that claims

« to restrict lawful abortions to NHS premises, except in cases of urgency when access to NHS premises is not possible and where no fee is paid ”

.[34]

In response to that, Amnesty International made a submission to the Justice Committee asking for the rejection of the full amendment. They denounced :

« « the restrictive abortion laws and practices and barriers to access safe abortion are gender-discriminatory, denying women and girls treatment only they need ”

Finally, a public consultation was launched by Justice Minister David Ford to amend the criminal law on abortion. This consultation takes into consideration cases where :

« there is a diagnosis in pregnancy that the foetus has a lethal abnormality”

[36] and cases where :

« women have become pregnant as a result of sexual crime”

.[36] The text also reminds :

« it is not a debate on the wider issues of abortion law – issues often labelled as 'pro-choice' and 'pro-life' ”

.[36] The consultation will be closed on the 17 January 2015.

Channel Islands

Although Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man are not part of the United Kingdom, as they are part of the Common Travel Area, people resident on these islands who choose to have an abortion have travelled to the UK since the Abortion Act 1967.[37]

Jersey

It is lawful in Jersey to have an abortion in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy[38] so long as specific criteria are met: more stringent criteria between 12 and 24 weeks. The criteria were established in the Termination of Pregnancy (Jersey) Law 1997.[39]

Guernsey

It is lawful in Guernsey to have an abortion in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy[40] so long as specific criteria are met: it is still lawful but with more stringent criteria between 12 and 24 weeks. The criteria were established in the Abortion (Guernsey) Law, 1997.[41] Other Channel Islands which are part of the Bailwick of Guernsey (including Alderney, Sark and Herm) also come under the articles of this Law.

Isle of Man

It is lawful in the Isle of Man to have an abortion in the first 24 weeks of pregnancy[42] so long as specific criteria are met. The criteria were established in the Termination of Pregnancy Act 1995.

History

Abortion was dealt with by the Ecclesiastical Courts in England, Scotland and Wales until the Reformation. It was dealt with under the laws of the Catholic Church. The Ecclesiastical Courts dealt mainly with the issue due to problems of evidence in such cases. The Ecclesiastical Courts had wider evidential rules and more discretion regarding sentencing.[43] Although the Ecclesiastical Courts heard most cases of abortion, some cases such as the Twinslayers Case were heard in the Secular Courts. The old Ecclesiastical Courts were made defunct after the Reformation.

Later, under Scottish common law, abortion was defined as a criminal offence unless performed for 'reputable medical reasons,' a definition sufficiently broad as to essentially preclude prosecution.

The law on abortion started to be codified in legislation and dealt with in government courts under sections 1 and 2 of Lord Ellenborough's Act (1803). The offences created by this statute were replaced by section 13 of the Offences against the Person Act 1828. Under section 1 of the 1803 Act and the first offence created by section 13 of the 1828 Act, the crime of abortion was subject, in cases where the woman was proved to have been quick with child to the death penalty or transportation for life. Under section 2 of the 1803 Act and the second offence created by section 13 of the 1828 Act (all other cases) the penalty was transportation for 14 years.

Section 13 of the 1828 Act was replaced by section 6 of the Offences against the Person Act 1837. This section made no distinction between women who were quick with child and those who were not. It eliminated the death penalty as a possible punishment.

Transportation was abolished by the Penal Servitude Act 1857, which replaced it with penal servitude.

Section 6 of the 1837 Act was replaced by section 58 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861. Section 59 of that created a new preparatory offence of procuring poison or instruments with intent to procure abortion.

From 1870 there was a steady decline in fertility, linked not to a rise in the use of artificial contraception but to more traditional methods such as withdrawal and abstinence. [44] This was linked to changes in the perception of the relative costs of childrearing. Of course, women did find themselves with unwanted pregnancies. Abortifacients were discreetly advertised and there was a considerable body of folklore about methods of inducing miscarriages. Amongst working class women violent purgatives were popular, pennyroyal, aloes and turpentine were all used. Other methods to induce miscarriage were very hot baths and gin, extreme exertion, a controlled fall down a flight of stairs, or veterinary medicines. So-called 'backstreet' abortionists were fairly common, although their bloody efforts could be fatal. Estimates of the number of illegal abortions varied widely: by one estimate, 100,000 women made efforts to procure a miscarriage in 1914, usually by drugs.

The criminality of abortion was redoubled in 1929, when the Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929 was passed. The Act criminalised the deliberate destruction of a Child "capable of being born alive". This was to close a lacuna in the law, identified by Lord Darling, which allowed for infants to be killed during birth, which would mean that the perpetrator could neither be prosecuted for abortion or murder.[45] There was included in the Act the presumption that all children in utero over 28 weeks gestation were capable of being born alive. Children in utero below this gestation were dealt with by way of evidence presented to determine whether or not they were capable of being born alive. In 1987, the Court of Appeal refused to grant an inunction to stop an abortion, ruling that a fetus between 18 and 21 weeks was not capable of being born alive.[46][47] In May 2007, a woman from Levenshulme, Manchester who in early 2006 had an illegal late-term abortion at 7½ months was convicted of child destruction under the Infant Life (Preservation) Act 1929. The case is believed to be the first of its kind in Britain.[48]

In 1938, the decision in Rex v. Bourne[49] allowed for further considerations to be taken into account. This case related to an abortion performed on a girl who had been raped. It extended the defence to abortion to include "mental and physical wreck" (McNaghtan LJ)

The gynaecologist concerned, Aleck Bourne, later became a founder member of the "pro-life" group SPUC[50] (Society for the Protection of Unborn Children) in 1966. The "pro-choice" group, the Abortion Law Reform Association, was formed in 1936.

In 1939 the Birkett Committee recommended a change to abortion laws but the intervention of World War II meant that all plans were shelved. Post-war, after decades of stasis certain high-profile tragedies, including thalidomide, and social changes brought the issue of abortion back into the political arena.

The 1967 Act

The Abortion Act 1967 sought to clarify the law. Introduced by David Steel and subject to heated debate it allowed for legal abortion on a number of grounds, with the added protection of free provision through the National Health Service. The Act was passed on 27 October 1967 and came into effect on 27 April 1968.[51]

The Act provided a defence for Doctors performing an abortion on any of the following grounds:

- To save the woman's life

- To prevent grave permanent injury to the woman's physical or mental health

- Under 28 weeks to avoid injury to the physical or mental health of the woman

- Under 28 weeks to avoid injury to the physical or mental health of the existing child(ren)

- If the child was likely to be severely physically or mentally handicapped

Before the Human Fertillisation and Embryology Act 1990 amended the Act, the Infant Life Preservation Act 1929 acted as a buffer to the Abortion Act 1967. This meant that abortions could not be carried out if the child was "capable of being born alive". There was therefore no statutory limit put into the Abortion Act 1967, the limit being that which the courts decided as the time at which a child could be born alive. The C v S case in 1987 reconfirmed that at 19–22 weeks a foetus was not capable of being born alive.[46]

The Act required that the procedure must be certified by two doctors before being performed.

The Act was amended in 1990 by the Human Fertillisation and Embryology Act 1990. The effect was that the Infant Life Preservation Act was decoupled from the Abortion Act thus allowing abortion to full term for disability, life of the mother and health of the mother. Some Members of Parliament claimed not to have been aware of the vast change the decoupling of the Infant Life Preservation Act 1929 would have on the Abortion Act 1967, particularly in relation to the unborn disabled child.[52] There was a failed attempt to revisit the amendment and have it overturned.[53]

Later laws

Changes to the Abortion Act 1967 were introduced in Parliament through the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990. The time limits were lowered from 28 to 24 weeks for most cases on the grounds that medical technology had advanced sufficiently to justify the change. Restrictions were removed for late abortions in cases of risk to life, fetal abnormality, or grave physical and mental injury to the woman.

Since 1967, members of Parliament have introduced a number of private member's bills to change the abortion law. Four resulted in substantive debate (1975, 1977, 1979 and 1987) but all failed. The Lane Committee investigated the workings of the Act in 1974 and declared its support.

In May 2008, MPs voted to retain the current legal limit of 24 weeks. Amendments proposing reductions to 22 weeks and 20 weeks were defeated by 304 to 233 votes and 332 to 190 votes respectively.[54]

Politicians from the unionist and nationalist parties in Northern Ireland joined forces on 20 June 2000 to block any extension of the Abortion Act 1967 to Northern Ireland where terminations are only allowed on a restricted basis.[15]

Statistics

Number of abortions

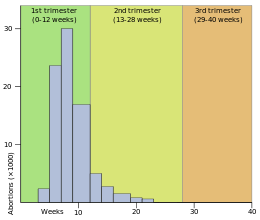

Post 1967 there was a rapid increase in the annual number of legal abortions, and a decline in Sepsis and death due to illegal abortions.[55] The rate of increase fell from the early 1970s and actually dipped from 1991-95 before rising again. The age group with the highest number of abortions per 1000 is amongst those aged 20–24. 2006 statistics for England & Wales revealed that 48% of abortions occurred to women over the age of 25, 29% were aged 20–24; 21% aged under 20 and 2% under 16.[56]

In 2004, there were 185,415 abortions in England and Wales. 87% of abortions were performed at 12 weeks or less and 1.6% (or 2,914 abortions) occurred after 20 weeks. Abortion is free to residents,[55] 82% of abortions were carried out by the National Health Service.[57]

The overwhelming majority of abortions (95% in 2004 for England and Wales) were certified under the statutory ground of risk of injury to the mental or physical health of the pregnant woman.[57]

Five years on to 2009, and the number of abortions has risen to 189,100. Of this number, 2,085 are as a result of doctors deciding that there is a substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped.[58]

In a written answer to Jim Allister the Northern Ireland health minister Edwin Poots disclosed that 394 abortions were carried out in Northern hospitals for the period 2005/06 to 2009/10 with the footnote that reasons for abortions were not gathered centrally.[59]

Attitudes to abortion

2004 Times/Populus poll

According to a 2004 The Times/Populus survey, Britons' feelings on abortion are:[60]

- 75% of Britons believe abortion should be legal

- 38% of Britons believe abortion should "always" be legal

- 36% of Britons believe abortion should "mostly" be legal

- 23% of Britons believe abortion should be illegal

- 20% of Britons believe abortion should "mostly" be illegal

- 4% of Britons believe abortion should "always" be illegal

NB: The survey compares the results to respondents' voting habits for mainland parties, indicating the possibility that Northern Ireland was not included in this survey.

2005 YouGov/Daily Telegraph poll

According to an August 2005 YouGov/Daily Telegraph survey, Britons' feelings toward abortion by gestational age are:[61]

- 2% said it should be permitted throughout pregnancy

- 25% support maintaining the current limit of 24 weeks

- 30% would back a measure to reduce the legal limit for abortion to 20 weeks

- 19% support a limit of 12 weeks

- 9% support a limit of fewer than 12 weeks

- 6% responded that abortion should never be allowed

2009 MORI poll

A 2009 poll by MORI[62] surveyed women's attitudes to abortion. Asking if all women should have the right of access abortion

- 37% Strongly agree

- 20% Tend to agree

- 12% Neither agree nor disagree

- 7% Tend to disagree

- 12% Strongly disagree

- 3% Don't know

- 9% preferred not to answer

Asked whether the limit should extend to the period 20–24 weeks of gestation regardless of her circumstances

- 22% agreed

- 61% disagreed

Approved methods

Methodology is time related - up to the ninth week medical abortion can be used (mifepristone was approved for use in Britain in 1991), from the seventh up to the fifteenth week suction or vacuum aspiration is most common (largely replacing the more damaging dilation and curettage technique), for the fifteenth to the eighteenth weeks surgical dilation and evacuation is most common. Approximately 30% of abortions are performed medically.[55]

In 2011, BPAS lost a High Court bid to force the Health Secretary to allow women undertaking early medical abortions in England, Scotland and Wales to administer the second dose of drug treatment at home.[63]

See also

References

- Halsbury's Laws of England

- Halsbury's Statutes

- Blackstone's Criminal Practice. 2012. Pages 226 to 230.

- Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice. 1999. Chapter 19. Section III. Paras 19-149 to 19-165.

- Ormerod. Smith and Hogan's Criminal Law. 13th ed. OUP. 2013. Section 16.5. Pages 602 to 615.

- Card, Cross and Jones: Criminal Law. 12th ed. Butterworths. 1992. Pages 230 to 235.

- Q&A: Abortion in NI. BBC.

- ↑ Revised text of s 1 of the Abortion Act 1967. Legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The Abortion Act 1967, section 6

- ↑ R v British Broadcasting Corporation, ex parte ProLife Alliance [2002] EWCA Civ 297 at [6], [2002] 2 All ER 756 at 761, CA

- ↑ Revised text of section 58 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861. Legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ Revised text of section 59 of the Offences against the Person Act 1861. Legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ The Abortion Act 1967, section 5(2); as read with section 6

- ↑ The Offences against the Person Act 1861 (24 & 25 Vict c 100), section 58; the Criminal Justice Act 1948 (11 & 12 Geo 6 c 58), section 1(1)

- ↑ The Offences against the Person Act 1861 (24 & 25 Vict c 100), section 59; the Penal Servitude Act 1891 (54 & 55 Vict c 69), section 1(1); the Criminal Justice Act 1948 (11 & 12 Geo 6 c 58), section 1(1)

- ↑ R v Buck and Buck, 44 Cr App R 213, Assizes, per Edmund Davies J.; R v Creamer [1966] 1 QB 72, 49 Cr App R 368, [1965] 3 WLR 583, [1965] 3 All ER 257, CCA

- ↑ See also Attorney General's Reference (No 3 of 1994) [1998] AC 245, [1997] 3 WLR 421, HL, [1996] 1 Cr App R 351, CA.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ The Abortion Act 1967, section 7(3)

- ↑ The Offences against the Person Act 1861 (24 & 25 Vict c 100), section 58; the Criminal Justice Act (Northern Ireland) 1953, section 1(1)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Birchard, Karen (2000). "Northern Ireland resists extending abortion Act". The Lancet 356 (9223): 52. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)73390-0.

- ↑ R v Bourne [1939] 1 KB 687

- ↑ Family Planning Association Of Northern Ireland v Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety [2004] NICA 39 at paragraph [51], per Nicholson LJ

- ↑ Quoted by Nicholson LJ at paragraph 56 of Family Planning Association Of Northern Ireland v Minister for Health, Social Services and Public Safety [2004 NICA 39

- ↑ [2004 NICA 39

- ↑ [2004 NICA 37

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ The Guardian

- ↑ , The Newsletter.

- ↑ They Work For You

- ↑ Socialist Worker,org

- ↑ , .

- ↑ Fearghal McKinney, .

- ↑ New Left Project

- ↑ .

- ↑ Attitudes to abortion

- ↑ , .

- ↑

- ↑ , .

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 , .

- ↑ HANSARD, July 1990 → Written Answers (Commons) → HEALTH

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ "1996: Guernsey votes to legalise abortion". BBC News. 13 June 1996.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.cambridge.org/us/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=0521894131

- ↑ Szreter; Fisher

- ↑ http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/lords/1928/jul/12/child-destruction-bill-hl

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 C v S [1988] QB 135, [1987] 2 WLR 1108, [1987] 1 All ER 1230, [1987] 2 FLR 505, (1987) 17 Fam Law 269, CA (Civ Div)

- ↑ "C. v. S., 25 February 1987". Annu Rev Popul Law 14: 41. 1987. PMID 12346721.

- ↑ "Baby destruction woman sentenced". BBC News. 24 May 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ R v Bourne [1939] 1 KB 687, [1938] 3 All ER 615, CCA

- ↑ http://www.spuc.org.uk/about/aims-activities

- ↑ House of Commons, Science and Technology Committee. "Scientific Developments Relating to the Abortion Act 1967." 1 (2006-2007). Print.

- ↑ Ann Widdecombe and pro-life MPs complained

- ↑ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm198990/cmhansrd/1990-06-21/Debate-16.html

- ↑ "MPs reject cut in abortion limit". BBC News. 21 May 2008.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Rowlands S (October 2007). "Contraception and abortion". J R Soc Med 100 (10): 465–8. doi:10.1258/jrsm.100.10.465. PMC 1997258. PMID 17911129.

- ↑ Government Statistical Service for the Department of Health. (June 19, 2007). Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2006. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/11/75/74/04117574.pdf

- ↑ Government Statistical Service for the Department of Health. (May 25, 2010). Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2009. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ↑

- ↑ "Q&A: Abortion law". BBC News. 21 June 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ YouGov. (2005-07-30). YouGov/Daily Telegraph Survey Results. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ↑ http://www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/poll.aspx?oItemId=2320

- ↑ Dyer, C. (2011). "Ruling prevents women taking second abortion pill at home". BMJ 342: d1045. doi:10.1136/bmj.d1045. PMID 21321014.

http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201011/ldhansrd/text/100719w0001.htm

External links

- UK National Statistics Office Abortion Data (England and Wales) - http://www.statistics.gov.uk/CCI/nscl.asp?ID=6249

- Scottish Health Statistics Abortion Data (Scotland) - http://www.isdscotland.org/isd/info3.jsp?pContentID=1918&p_applic=CCC&p_service=Content.show&

| ||||||||||