Abel Streight

| Abel Delos Streight | |

|---|---|

Abel D. Streight | |

| Born |

June 17, 1828 Wheeler, New York |

| Died |

May 27, 1892 (aged 63) Indianapolis, Indiana |

| Place of burial | Crown Hill Cemetery |

| Allegiance |

Union |

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1861 - 1865 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Abel Delos Streight (June 17, 1828 – May 27, 1892) was a peace time lumber merchant and publisher, and was a Union Army general in the American Civil War. His command precipitated a notable cavalry raid in 1863, known as Streight's Raid. He later was a politician, and served as a State Senator in Indiana, for two terms.

Early life and Civil War

Abel Streight was born in Wheeler, New York, son of Asa Streight and Lydia Spaulding Streight.[1] On 14 Jan 1849 he married Lavina or Lovina McCarty, who was born 1830, Bath Twp., Steuben Co., NY and died 5 Jun 1910, Marion Co., IN.[2] He moved to Cincinnati, as a young man, and by 1859 was living in Indianapolis, where he was a publisher of books and maps.

Streight was appointed colonel of the 51st Indiana Infantry regiment on December 12, 1861. His regiment was soon attached to the Union Army of the Cumberland.

Streight and his regiment saw very limited action during the first two years of their service, which is said to have disappointed him greatly.

In 1863, he proposed a plan to Brig. Gen. James A. Garfield (chief of staff of the Army of the Cumberland) that he be allowed to raise a force to make to raid deeply into the South. His proposal was to disrupt of the Western & Atlantic Railroad from Chattanooga to Atlanta, which carried supplies to the Confederate Army of Tennessee. The Union Army's commander, William S. Rosecrans, gave him permission.

Union forces from Streight's own 51st Indiana, 73rd Indiana Infantry, 80th Illinois Infantry, and 3rd Ohio Infantry regiments were placed under Streight's command. This force encompassed approximately 1,700 troops. The original intent was to have this force mounted suitably for fast travel and attacks; however, due largely to wartime shortages, Streight's brigade were equipped with mules. This obvious disadvantage, combined with Streight's own inexperience, was to prove disastrous.

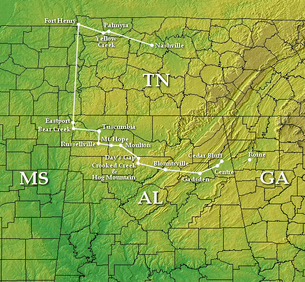

Steight led this force to Nashville, departed Tuscumbia, Alabama, on April 26, 1863, and then to Eastport, Mississippi. From there he decided to push to the southeast, initially screened by another Union force commanded by Brig. Gen. Grenville Dodge. On April 30, Streight's brigade arrived at Sand Mountain, where he was intercepted by a Confederate cavalry force under Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest and harassed for several days. Streight's force won the Battle of Day's Gap but the battle set off a series of skirmishes that eventually led the Union forces being surrounded and captured.[3] Streight himself was captured and taken to Libby Prison as a prisoner of war.

After ten months of incarceration, Streight and 107 other soldiers escaped from prison by tunnelling from their barracks to freedom. Eventually, Streight was able to cross through enemy territory and, on his return, gave a debriefing report to his Union commanders.

Eventually Streight was restored to active duty being placed in command of the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, IV Corps. He participated in the battles of Franklin and Nashville. Streight was given a brevet promotion to brigadier general in the volunteer army dated March 13, 1865. He resigned from the army on March 16, 1865.

Postbellum career

Streight resigned his command and left the army in March 1865, having achieved the rank of brevet brigadier general. In 1866, he and his wife built a house on Washington Street in Indianapolis. In 1876, Streight ran successfully for a seat in the Indiana Senate, serving a two year term. In 1880, he ran unsuccessfully as the Republican candidate for governor of Indiana. In 1888, he was once again elected as State Senator. He died in Indianapolis four years later, in 1892. He is buried there in Crown Hill Cemetery.

Streight was the author of The Crisis of Eighteen Hundred and Sixty-one in the Government of the United States, published in 1861.

Streight's wife Lovina joined her husband on his southern campaign, often ministering help to wounded men during the battle. She was captured three times and exchanged for prisoners. When Abel died in 1892 she had him buried in the front yard of their home, stating, "I never knew where he was in life, but now I can find him."[4] Lovina Streight was known as the "Mother of the 51st", and upon her death in 1910, her funeral was afforded full military honors. It was said at the time that her funeral drew the largest crowd of mourners to Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis since the funeral of President Benjamin Harrison.[5] In her will, she directed that the family mansion should become a home for aged women; however, relatives successfully challenged the will on the grounds that she was of “unsound mind.” The main arguments used by the plaintiffs were that she believed in spiritualism and was under the influence of B. Frank Schmid, a spiritualist.[6]

See also

References

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- ↑ The Ancestors and Descendants of Rev. Phineas Spaulding (1759-1838), by Michael Spaulding, (c) 2000, page 48.

- ↑ The Ancestors and Descendants of Rev. Phineas Spaulding (1759-1838), by Michael Spaulding, (c) 2000, page 48.

- ↑ Day's Gap

- ↑ Willett, Robert L.; The Lightning Mule Brigade, Carmel, IN, 1999, p. 196.

- ↑ obit. of Lavina Streight, Indianapolis Star, 7 & 9 Jun 1910, p. 1

- ↑ the trial, held in Shelbyville, IN, over Lavina's will was a big story in its day, and is covered in the following newspapers: Indianapolis News, 27 Aug 1910, p. 2, 5 Apr 1911, p. 1, 16 Apr 1911, p. 8; Indianapolis Star, 28 Apr 1911, p. 1; Shelbyville Democrat, 4-28 Apr 1911

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |