Abbe sine condition

The Abbe sine condition is a condition that must be fulfilled by a lens or other optical system in order for it to produce sharp images of off-axis as well as on-axis objects. It was formulated by Ernst Abbe in the context of microscopes.

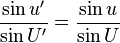

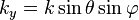

The mathematical condition is as follows:

where the variables u, U are the angles (relative to the optic axis) of any two rays as they leave the object, and u′, U′ are the angles of the same rays where they reach the image plane (say, the film plane of a camera). For example, (u,u′) might represent a paraxial ray (i.e., a ray nearly parallel with the optic axis), and (U,U′) might represent a marginal ray (i.e., a ray with the largest angle admitted by the system aperture); the condition is general, however, and does not only apply to those rays.

Put in words, the sine of the output angle should be proportional to the sine of the input angle.

Magnification and the Abbe sine condition

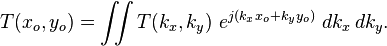

Using the framework of Fourier optics, we may easily explain the significance of the Abbe sine condition. Say an object in the object plane of an optical system has a transmittance function of the form, T(xo,yo). We may express this transmittance function in terms of its Fourier transform as

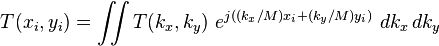

Now, assume for simplicity that the system has no image distortion, so that the image plane coordinates are linearly related to the object plane coordinates via the relation

where M is the system magnification. Let's now re-write the object plane transmittance above in a slightly modified form:

where we have simply multiplied and divided the various terms in the exponent by M, the system magnification. Now, we may substitute the equations above for image plane coordinates in terms of object plane coordinates, to obtain,

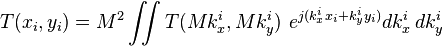

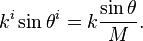

At this point we can propose another coordinate transformation (i.e., the Abbe sine condition) relating the object plane wavenumber spectrum to the image plane wavenumber spectrum as

to obtain our final equation for the image plane field in terms of image plane coordinates and image plane wavenumbers as:

From Fourier optics, we know that the wavenumbers can be expressed in terms of the spherical coordinate system as

If we consider a spectral component for which  , then the coordinate transformation between object and image plane wavenumbers takes the form

, then the coordinate transformation between object and image plane wavenumbers takes the form

This is another way of writing the Abbe sine condition, which simply reflects Heisenberg's uncertainty principle for Fourier transform pairs, namely that as the spatial extent of any function is expanded (by the magnification factor, M), the spectral extent contracts by the same factor, M, so that the space-bandwidth product remains constant.