Abbas I of Persia

| Shah Abbās I شاه عَباس کبير | |

|---|---|

|

Shahanshah of Iran | |

| |

| Shahanshah of Iran | |

| Reign | 1 October 1588 – 19 January 1629 |

| Coronation | 1588 |

| Predecessor | Mohammad I |

| Successor | Safi |

| Queen | Tinatin (Leili sultan) |

| Dynasty | Safavid |

| Father | Mohammed Khodabanda |

| Mother | Khayr al-Nisa Begum |

| Born |

27 January 1571 Herat (now in Afghanistan) |

| Died |

19 January 1629 (aged 57) Mazandaran, Iran |

| Burial |

1629 Kashan |

| Religion | Shia Islam |

Shāh Abbās the Great (or Shāh Abbās I) (Persian: شاه عَباس بُزُرگ) (27 January 1571 – 19 January 1629) was the 5th Safavid king (Shah) of Iran, and is generally considered the greatest ruler of the Safavid dynasty. He was the third son of Shah Mohammad Khodabanda.[1]

Although Abbas would preside over the apex of the Persian Empire's military, political and economic power, he came to the throne during a troubled time for Iran. Under his weak-willed father, the country was riven with discord between the different factions of the Qizilbash army, who killed Abbas' mother and elder brother. Meanwhile, Iran's enemies, the Ottoman Empire and the Uzbeks, exploited this political chaos to seize territory for themselves. In 1588, one of the Qizilbash leaders, Murshid Qoli Khan, overthrew Shah Mohammed in a coup and placed the 16-year-old Abbas on the throne. But Abbas was no puppet and soon seized power for himself.

With his leadership and the help of the newly created layers in his Persian society, started and created by his predecessors but significantly expanded under Abbas and composed of hundreds of thousands of Circassians, Georgians, and Armenians he managed to completely crush the power of the Qizilbash in the civil administration, royal house, and the military. By this and his reforming of the army, it enabled him to fight the Ottomans and Uzbeks and reconquer Iran's lost provinces. He also took back land from the Portuguese and the Mughals, and expanded Iranian rule and influence in the North Caucasus. Abbas was a great builder and moved his kingdom's capital from Qazvin to Isfahan, making the city the pinnacle of Safavid architecture. In his later years, the shah became suspicious of his own sons and had them killed or blinded.

Early years

Abbas was born in Herat (now in Afghanistan, then one of the two chief cities of Khorasan) as the third son of the royal prince Mohammad Khodabanda and his wife Khayr al-Nisa Begum (known as "Mahd-i Ulya"), the daughter of the Marashi ruler of the Mazandaran province, who claimed descent from the fourth Shi'a Imam Zayn al-Abidin.[2][3] At the time of his birth, Abbas' grandfather Shah Tahmasp I was the Shah of Iran. Abbas' parents gave him to be nursed by Khani Khan Khanum, the mother of the governor of Herat, Ali Qoli Khan Shamlu.[4][nb 1] When Abbas was four, Tahmasp sent his father to stay in Shiraz where the climate was better for his fragile health. Tradition dictated that at least one prince of the royal blood had to reside in Khorasan, so Tahmasp appointed Abbas as the nominal governor of the province, despite his young age, and Abbas was left behind in Herat.[6]

In 1578, Abbas' father became Shah of Iran. Abbas' mother soon came to dominate the government, but she had little time for Abbas, preferring to promote the interests of his elder brother Hamza.[7] The queen consort antagonised leaders of the powerful Qizilbash army, who plotted against her and murdered her on 26 July 1579, reportedly for having an affair.[8][9][10] Mohammad was a weak sovereign, incapable of preventing Iran's rivals, the Ottoman Empire and the Uzbeks, from invading the country or stopping factional feuding among the Qizilbash.[8][11] The young prince, Hamza, was more promising and led a campaign against the Ottomans, but he was murdered suspiciously in 1586.[12] Attention now turned to Abbas.[13]

At the age of 14, Abbas had come under the guardianship of Murshid Qoli Khan, one of the Qizilbash leaders in Khorasan. When a large Uzbek army invaded Khorasan in 1587, Murshid decided the time was right to overthrow Shah Mohammad.[14][15] He rode to the Safavid capital Qazvin with the young prince and pronounced him king, on 16 October 1587.[16][17] Mohammad made no objection against his deposition and handed the royal insignia over to his son, the following year, on 1 October 1588.[nb 2] Abbas was 17 years old.[18][19]

Absolute monarch

Abbas takes control

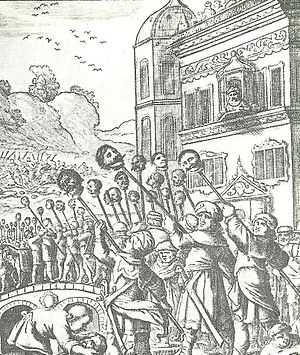

Copper engraving by Dominicus Custos, from his Atrium heroicum Caesarum pub. 1600–1602.

The kingdom Abbas inherited was in a desperate state. The Ottomans had seized vast territories in the west and the north-west (including the major city of Tabriz) and the Uzbeks had overrun half of Khorasan in the north-east. Iran itself was riven by fighting between the various factions of the Qizilbash, who had mocked royal authority by killing the queen in 1579 and the grand vizier Mirza Salman Jabiri in 1583.

First, Abbas settled his score with his mother's killers, executing three of the ringleaders of the plot and exiling four others.[20] His next task was to free himself from the power of Murshid Qoli Khan. Murshid made Abbas marry Hamza's widow and a Safavid cousin, and began distributing important government posts among his own friends, gradually confining Abbas to the palace.[21] Meanwhile the Uzbeks continued their conquest of Khorasan. When Abbas heard they were besieging his old friend Ali Qoli Khan Shamlu in Herat he pleaded with Murshid to take action. Fearing a rival, Murshid did nothing until the news came that Herat had fallen and the Uzbeks had slaughtered the entire population. Only then did he set out on campaign to Khorasan.[22] But Abbas planned to avenge the death of Ali Qoli Khan and he suborned four Qizilbash leaders to kill Murshid after a banquet on 23 July 1589. With Murshid gone, Abbas could now rule Iran in his own right.[23][24]

Abbas decided he must re-establish order within Iran before he took on the foreign invaders. To this end he made a humiliating peace treaty – known as the Treaty of Istanbul – with the Ottomans in 1589/90, ceding them the provinces of Azerbaijan, Karabagh, Ganja, Dagestan, and Qarajadagh as well as parts of Georgia, Luristan and Kurdistan. This demeaning treaty even ceded the previous capital of Tabriz to the Ottomans.[25][26][27]

Reducing the power of the Qizilbash

The Qizilbash had provided the backbone of the Safavid army from the very beginning of Safavid rule and they also occupied many posts in the government. To counterbalance their power, Abbas turned to another recently introduced layer in Iranian society started by Shah Tahmasp I; the ghulams (a word literally meaning "slaves"). These were Georgians, Circassians and Armenians who had been imported en masse (by conquest and slave trade), had converted to Islam and had taken up service in the army, royal household or the civil administration.[28]

Abbas would greatly expand this program, systematically replacing the Qizilbash from the highest offices of the state with these Caucasian ghulams. This crucial change would resolve budgetary problems too, as it restored the Shah's full control of the provinces formerly governed by the Qizilbash chiefs, the revenues of which supplemented the royal treasury.

Within short time, Georgians, Circassians, and Armenians had been appointed to many of the highest offices of the state. They would continue to play a crucial role during the rest of the Safavid Dynasty and in Iran itself for many more centuries.[29] These ghulams included the Georgian Allahverdi Khan, who became leader of the ghulam regiments in the army as well as governor of the rich province of Fars, and the Circassian ghulam Uzun Behbud Beg, who would kill Abbas' own son, Mohammad-Baqer Safi Mirza, whose mother was also a Circassian by Abbas' own order.[30]

However, since the time of Tahmasp' death, these increasing Georgians and Circassians were already heavily vying with the Qizilbash for power and were often involved in court intrigues. Most of the Safavid Queen-Mothers and dignitaries from the mid 16th century were already either Circassian or Georgian. They would compete against the other mothers and possible successors in the Safavid court and harem in order to get their own sons on the throne. This would only increase under Abbas and his successors, creating many intrigues that would weaken the dynasty considerably.[29]

Another important task that Abbas needed to perform was while utilizing his allies in the Qizilbash, eradicating those tribes that he considered his enemies. First and foremost of these were the Qajars. The Ustajlus were a needed ally in this period, when he stripped the power from all those Qizilbash tribes that supported other princes.[31]

Reforming the army

Abbas needed ten years to get his army in order to be able to confront his enemies. During this period, the Uzbeks and the Mughals' took swaths of territory from Persia.[32] Abbas needed to reform the army before he could hope to confront the Ottoman and Uzbek invaders. He also used military reorganisation as another way of sidelining the Qizilbash.[33] Instead, he created a standing army of 10,000 ghulams (always conscripted from ethnic Georgians and Circassians) and Iranians to fight alongside the traditional, feudal force provided by the Qizilbash. The new army regiments had no loyalty but to the shah. They consisted of 10,000–15,000 cavalry or squires (ghulam) armed with muskets and other weapons (then the largest cavalry in the world[34]), a corps of musketeers, or tufangchiyan,[28] (12,000 strong) and one of artillery, called tupchiyan[28] (also 12,000 strong). In addition Abbas had a personal bodyguard of 3,000 also cavalry (ghulams). This force amounted to a total of near 40,000 soldiers paid for and beholden to the Shah.[28][35][36]

Abbas also greatly increased the number of cannons at his disposal, permitting him to field 500 in a single battle.[36] Ruthless discipline was enforced and looting was severely punished. Abbas was also able to draw on military advice from a number of European envoys, particularly from the English adventurers Sir Anthony Shirley and his brother Robert Shirley, who arrived in 1598 as envoys from the Earl of Essex on an unofficial mission to induce Persia into anti-Ottoman alliance.[37]

Consolidation of the Empire

Abbas then began deposing the vassal rulers of Persia, he first started with Khan Ahmad Khan, the ruler of Gilan, who had disobeyed the orders of Abbas when he asked his daughter to marry his son Safi Mirza.[38] This resulted in a Safavid invasion of Gilan in 1591 under one of Abbas' favorites, Farhad Khan Qaramanlu. In 1593–94, Jahangir III, the Paduspanid ruler of Nur, Iran, traveled to the court of the Abbas, where he handed over his domains to him, and spend the rest of his life in a property at Saveh, which Abbas had given to him. In 1597, Abbas deposed the Khorshidi ruler of Lar. One year later, Jahangir IV, the Paduspanid ruler of Kojur, killed two prominent Safavid nobles during a festival in Qazvin. This made Abbas invade his domains in 1598, where he besieged Kojur. Jahangir managed to flee, but was captured and killed by a Pro-Safavid Paduspanid named Hasan Lavasani.[39]

Reconquest

War against the Uzbeks

Abbas' first campaign with his reformed army was against the Uzbeks who had seized Khorasan and were ravaging the province. In April 1598 he went on the attack. One of the two main cities of the province, Mashhad, was easily recaptured but the Uzbek leader Din Mohammed Khan was safely behind the walls of the other chief city, Herat. Abbas managed to lure the Uzbek army out of the town by feigning a retreat. A bloody battle ensued on 9 August 1598, in the course of which the Uzbek khan was wounded and his troops retreated (the khan was murdered by his own men on the way). However, during the battle, Farhad Khan had fled after being wounded, but was later accused of fleeing due to his cowardice. He was nevertheless forgiven by Abbas, who wanted to appoint him as the governor of Herat, which Farhad Khan refused. According to Oruch Beg, the refusal of Farhad Khan made Abbas feel that he had been insulted. However, due the arrogant behavior of Farhad Khan and his suspected treason, which had made him become a threat to Abbas, who already did not have much trust to the Qizilbash—made Abbas have him executed.[40] Abbas then converted Gilan and Mazandaran into the crown domain (khassa), and appointed Allahverdi Khan as the new commander-in-chief of the Safavid army.[40]

By 1599, Abbas had conquered not only Herat and Mashhad, but had moved as far east as Balkh. This would be a short-lived victory and he would eventually have to settle on controlling only some of this conquest, as when the new rule of the Khanate of Khiva, Baqi Muhammad Khan attempted to retake Balkh, Abbas found his troops were still no match for the Uzbeks. By 1603, the lines had stabilized, albeit with the loss of the majority of the Persian artillery, and Abbas was able to hold onto most of Khorassan, including Herat, Sabzavar, Farah, and Nisa.[41]

Abbas' north-east frontier was now safe for the time being and he could turn his attention to the Ottomans in the west.[42] After defeating the Uzbeks, he moved his capital from Qazvin to Isfahan.[32]

War against the Ottomans

The Safavids had not yet beaten their archrival, the Ottomans, in a straight fight. After a particularly arrogant series of demands from the Turkish ambassador, the shah had him seized, had his beard shaved and sent it to his master, the sultan, in Constantinople. This was a declaration of war.[43] Abbas first recaptured Nahavand and destroyed the fortress in the city, which the Ottomans had planned to use as an advance base for attacks on Iran.[44] The next year, Abbas pretended he was setting off on a hunting expedition to Mazandaran with his men. This was merely a ruse to deceive the Ottoman spies in his court – his real target was Azerbaijan.[45] He changed course for Qazvin where he assembled a large army and set off to retake Tabriz, which had been in Ottoman hands for a while.

For the first time, the Iranians made great use of their artillery and the town – which had been ruined by Ottoman occupation – soon fell.[46] Abbas set off to besiege Yerevan, one of the main Turkish strongholds in the Caucasus. It finally fell in June 1604 and with it the Ottomans lost the loyalty of most Armenians, Georgians and other Caucasians. But Abbas was unsure how the new sultan, Ahmed I, would respond and withdrew from the region using scorched earth tactics.[47] For a year, neither side made a move, but in 1605, Abbas sent his general Allahverdi Khan to meet Ottoman forces on the shores of Lake Van. On 6 November 1605 the Iranians led by Abbas scored a decisive victory over the Ottomans at Sufiyan, near Tabriz.[48] In the Caucasus, during the war Abbas also managed to capture Kabardino-Balkaria. The Persian victory was recognised in the Treaty of Nasuh Pasha in 1612, decisively granting them back suzerainty over most of the Caucasus.

Several years of peace followed as the Ottomans carefully planned their response. But their secret training manoeuvres were observed by Iranian spies. Abbas learnt the Ottoman plan was to invade via Azerbaijan, take Tabriz then move on to Ardabil and Qazvin, which they could use as bargaining chips to exchange for other territories. The shah decided to lay a trap. He would allow the Ottomans to enter the country, then destroy them. He had Tabriz evacuated of its inhabitants while he waited at Ardabil with his army. In 1618, an Ottoman army of 100,000 led by the grand vizier, invaded and easily seized Tabriz.[49] The vizier sent an ambassador to the shah demanding he make peace and return the lands taken since 1602.[50] Abbas refused and pretended he was ready to set fire to Ardabil and retreat further inland rather than face the Ottoman army.[51] When the vizier heard the news, he decided to march on Ardabil right away. This was just what Abbas wanted. His army of 40,000 was hiding at a crossroads on the way and they ambushed the Ottoman army in a battle, which ended in complete victory for the Iranians.[52]

In 1623, Abbas decided to take back Mesopotamia, which had been lost by his grandfather Tahmasp.[53] Profiting from the confusion surrounding the accession of the new sultan Murad IV, he pretended to be making a pilgrimage to the Shi'ite shrines of Kerbala and Najaf, but used his army to seize Baghdad.[54] He was distracted by the rebellion in Georgia in 1624 that allowed an Ottoman force to besiege Baghdad, but the shah came to its relief the next year and crushed the Turkish army decisively.[55] In 1638, however, after Abbas' death, the Ottomans retook Baghdad and the Iranian–Ottoman border was finalised.

Kandahar and the Mughals

The Safavids were traditionally allied with the Mughals in India against the Uzbeks, who coveted the province of Khorasan. The Mughal emperor Humayun had given Abbas' grandfather, Shah Tahmasp, the province of Kandahar as a reward for helping him back to his throne.[56][57] In 1590, profiting from the confusion in Iran, Humayun's successor Akbar seized Kandahar. Abbas continued to maintain cordial relations with the Mughals, while always asking for the return of Kandahar.[58] Finally, in 1620, a diplomatic incident in which the Iranian ambassador refused to bow down in front of the Emperor Jahangir led to war.[59] India was embroiled in civil turmoil and Abbas found he only needed a lightning raid to take back Kandahar in 1622.

After the conquest, he was very conciliatory to Jahangir, claiming he had only taken back what was rightly his and disavowing any further territorial ambitions.[60][61] Jahangir was not appeased but he was unable to recapture the province. A childhood friend of Abbas named Ganj Ali Khan was then appointed as the governor of city, which he would govern until his death in 1624/5.[62][63]

War against the Portuguese

During the 16th century the Portuguese had established bases in the Persian Gulf.[64] In 1602, the Iranian army under the command of Imam-Quli Khan Undiladze managed to expel the Portuguese from Bahrain.[65] In 1622, with the help of four English ships, Abbas retook Hormuz from the Portuguese in the Capture of Ormuz (1622).[66] He replaced it as a trading centre with a new port, Bandar Abbas, nearby on the mainland, but it never became as successful.[67]

The shah and his subjects

Isfahan: a new capital

Abbas moved his capital from Qazvin to the more central and more Persian Isfahan in 1598. Embellished by a magnificent series of new mosques, baths, colleges, and caravansarais, Isfahan became one of the most beautiful cities in the world. As Roger Savory writes, "Not since the development of Baghdad in the eighth century A.D. by the Caliph al-Mansur had there been such a comprehensive example of town-planning in the Islamic world, and the scope and layout of the city centre clear reflect its status as the capital of an empire."[68] Isfahan became the centre of Safavid architectural achievement, with the mosques Masjed-e Shah and the Masjed-e Sheykh Lotfollah and other monuments like the Ali Qapu, the Chehel Sotoun palace, and the Naghsh-i Jahan Square.

In making Isfahan the center of Safavid Empire, Abbas utilized the Armenian people, who he forcibly relocated to Isfahan. Once they were settled, he allowed them considerable freedom and encouraged them to continue in their silk trade. Silk was an integral part of the economy and considered to be the best form of hard currency available. The Armenians had already established trade networks that allowed Abbas to strengthen the economy of not just the empire but Isfahan also.[69]

Arts

Abbas' painting ateliers (of the Isfahan school established under his patronage) created some of the finest art in modern Iranian history, by such illustrious painters as Reza Abbasi, Muhammad Qasim and others. Despite the ascetic roots of the Ṣafavid dynasty and the religious injunctions restricting the pleasures lawful to the faithful, the art of Abbas' time denotes a certain relaxation of the strictures. Historian James Saslow interprets the portrait by Muhammad Qasim as showing that the Muslim taboo against wine, as well as that against male intimacy, "were more honored in the breach than in the observance".[70] Abbas brought 300 Chinese potters to Iran to enhance local production of Chinese-style ceramics.[71] Ella Sykes's remarks,

Early in the seventeenth century, Shah Abbas imported Chinese workmen into his country to teach his subjects the art of making porcelain, and the Chinese influence is very strong in the designs on this ware. Chinese marks are also copied, so that to scratch an article is sometimes the only means of proving it to be of Persian manufacture, for the Chinese glaze, hard as iron, will take no mark.[72]

Under Abbas' reign, carpet weaving became an important part of the Persian culture, as wealthy Europeans started importing rugs. Silk production became a monopoly of the crown, and manuscripts, bookbinding, and ceramics were important exports also.[32]

Religious attitude and religious minorities

Like all other Safavid monarchs, Abbas was a Shi'ite Muslim. He had a particular veneration for Imam Hussein.[73] In 1601, he made a pilgrimage on foot from Isfahan to Mashhad, site of the shrine of Imam Reza, which he restored (it had been despoiled by the Uzbeks).[74] Since Sunni Islam was the religion of Iran's main rival, the Ottoman Empire, Abbas often treated Sunnis living in western border provinces harshly.[75]

Abbas was generally tolerant of Christianity. The Italian traveller Pietro della Valle was astonished at the Shah's knowledge of Christian history and theology and establishing diplomatic links with European Christian states was a vital part of the shah's foreign policy.[76] Christian Armenia was a key province on the border between Abbas' realm and the Ottoman Empire. From 1604 Abbas implemented a "scorched earth" policy in the region to protect his north-western frontier against any invading Ottoman forces, a policy that involved the forced resettlement of around 300,000 Armenians from their homelands. Many were transferred to New Julfa, a town the shah had built for the Armenians near his capital Isfahan. Thousands of Armenians died on the journey. According to Bomati and Nahavandi, of 56,000 who left Armenia, only 30,000 reached the new town.[77] Those who survived enjoyed considerable religious freedom in New Julfa, where the shah built them a new cathedral. Abbas' aim was to boost the Iranian economy by encouraging the Armenian merchants who had moved to New Julfa. As well as religious liberties, he also offered them interest-free loans and allowed the town to elect its own mayor (kalantar).[78] Other Armenians were transferred to the provinces of Gilan and Mazandaran. These were less lucky. Abbas wanted to establish a second capital in Mazandaran, Farahabad, but the climate was unhealthy and malarial. Many settlers died and others gradually abandoned the city.[79][80][81]

In 1614–16 during the Ottoman-Safavid War (1603-1618), Abbas suppressed a rebellion led by his formerly most loyal Georgian subjects Luarsab II and Teimuraz I in the Kingdom of Kakheti. In two punitive campaigns he devastated Tblisi, killed 60–70,000 Kakheti Georgian peasants, and deported between 130,000-200,000 Georgian captives to Iran.[82][83] After having fully secured the region, he executed the rebellious Luarsab II of Kartli and later had the Georgian queen Ketevan tortured to death when she refused to renounce Christianity.[84][85]

Contacts with Europe

Abbas' tolerance towards Christians was part of his policy of establishing diplomatic links with European powers to try to enlist their help in the fight against their common enemy, the Ottoman Empire. The idea of such an anti-Ottoman alliance was not a new one – over a century before, Uzun Hassan, then ruler of part of Iran, had asked the Venetians for military aid – but none of the Safavids had made diplomatic overtures to Europe and Abbas' attitude was in marked contrast to that of his grandfather, Tahmasp I, who had expelled the English traveller Anthony Jenkinson from his court on hearing he was a Christian.[86] For his part, Abbas declared that he "preferred the dust from the shoe soles of the lowest Christian to the highest Ottoman personage".[87]

In 1599, Abbas sent his first diplomatic mission to Europe.[88] The group crossed the Caspian Sea and spent the winter in Moscow, before proceeding through Norway, Germany (where it was received by Emperor Rudolf II) to Rome where Pope Clement VIII gave the travellers a long audience. They finally arrived at the court of Philip III of Spain in 1602.[89] Although the expedition never managed to return to Iran, being shipwrecked on the journey around Africa, it marked an important new step in contacts between Iran and Europe and Europeans began to be fascinated by the Iranians and their culture – Shakespeare's 1601–02 Twelfth Night, for example, makes two references (at II.5 and III.4) to 'the Sophy', then the English term for the Shahs of Iran.[90][91] Persian fashions—such as shoes with heels, for men—were enthusiastically adopted by European aristocrats.[34] Henceforward, the number of diplomatic missions to and fro greatly increased.[92]

The shah had set great store on an alliance with Spain, the chief opponent of the Ottomans in Europe. Abbas offered trading rights and the chance to preach Christianity in Iran in return for help against the Ottomans. But the stumbling block of Hormuz remained, a port that had fallen into Spanish hands when the King of Spain inherited the throne of Portugal in 1580. The Spanish demanded Abbas break off relations with the English East India Company before they would consider relinquishing the town. Abbas was unable to comply.[92] Eventually Abbas became frustrated with Spain, as he did with the Holy Roman Empire, which wanted him to make his 170,000 Armenian subjects swear allegiance to the Pope but did not trouble to inform the shah when the Emperor Rudolf signed a peace treaty with the Ottomans.[93] Contacts with the Pope, Poland and Moscow were no more fruitful.[94]

More came of Abbas' contacts with the English, although England had little interest in fighting against the Ottomans. The Sherley brothers arrived in 1598 and helped reorganise the Iranian army. The English East India Company also began to take an interest in Iran and in 1622 four of its ships helped Abbas retake Hormuz from the Portuguese in the capture of Hormuz. It was the beginning of the East India Company's long-running interest in Iran.[95]

Family tragedies and death

Of Abbas' five sons, three had survived past childhood, so the Safavid succession seemed secure. He was on good terms with the crown prince, Mohammed Baqir Mirza (born 1587; better known in the West as Safi Mirza).[96] In 1614, however, during a campaign in Georgia, the shah heard rumours that the prince was conspiring against his life with a leading Circassian, Farhad Beg. Shortly after, Mohammed Baqir broke protocol during a hunt by killing a boar before the shah had chance to put his spear in. This seemed to confirm Abbas' suspicions and he sunk into melancholy; he no longer trusted any of his three sons.[97] In 1615, he decided he had no choice but to have Mohammed killed. A Circassian named Behbud Beg executed the Shah's orders and the prince was murdered in a hammam in the city of Resht. The shah almost immediately regretted his action and was plunged into grief.[98]

In 1621, Abbas fell seriously ill. His heir, Mohammed Khodabanda, thought he was on his deathbed and began to celebrate his accession to the throne with his Qizilbash supporters. But the shah recovered and punished his son with blinding, which would disqualify him from ever taking the throne.[99] The blinding was only partially successful and the prince's followers planned to smuggle him out of the country to safety to the Mughals whose aid they would use to overthrow Abbas and install Mohammed on the throne. But the plot was betrayed, the prince's followers were executed and the prince himself imprisoned in the fortress of Alamut where he would later be murdered by Abbas' successor, Shah Safi.[100]

Imam Qoli Mirza, the third and last son, now became the crown prince. Abbas groomed him carefully for the throne but, for some reason, in 1627, he had him partially blinded and imprisoned in Alamut.[101]

Unexpectedly, Abbas now chose as heir the son of Mohammed Baqir Mirza, Sam Mirza, a cruel and introverted character who was said to loathe his grandfather because of his father's murder. It was he who in fact did succeed Shah Abbas at the age of seventeen in 1629, taking the name Shah Safi. Abbas's health was troubled from 1621 onwards. He died at his palace in Farahabad on the Caspian coast in 1629 and was buried in Kashan.[102]

Character and legacy

According to Roger Savory: "Shah Abbas I possessed in abundance qualities which entitle him to be styled 'the Great'. He was a brilliant strategist and tactician whose chief characteristic was prudence. He preferred to obtain his ends by diplomacy rather than war, and showed immense patience in pursuing his objectives."[103] In Michael Axworthy's view, Abbas "was a talented administrator and military leader, and a ruthless autocrat. His reign was the outstanding creative period of the Safavid era. But the civil wars and troubles of his childhood (when many of his relatives were murdered) left him with a dark twist of suspicion and brutality at the centre of his personality."[104]

The Cambridge History of Iran rejects the view that the death of Abbas marked the beginning of the decline of the Safavid dynasty as Iran continued to prosper throughout the 17th century, but blames him for the poor statesmanship of the later Safavid shahs: "The elimination of royal princes, whether by blinding or immuring them in the harem, their exclusion from the affairs of state and from contact with the leading aristocracy of the empire and the generals, all the abuses of the princes' education, which were nothing new but which became the normal practice with Abbas at the court of Isfahan, effectively put a stop to the training of competent successors, that is to say, efficient princes prepared to meet the demands of ruling as kings."[105]

Abbas gained strong support from the common people. Sources report him spending much of his time among them, personally visiting bazaars and other public places in Isfahan.[106] Short in stature but physically strong until his health declined in his final years, Abbas could go for long periods without needing to sleep or eat and could ride great distances. At the age of 19 Abbas shaved off his beard, keeping only his moustache, thus setting a fashion in Iran.[107][108]

Offspring

Sons

- Prince Shahzadeh Soltan Mohammad Baqer Feyzi Mirza (b. 15 September 1587, Mashhad, Khorasan-k. 25 January 1615, Rasht, Gilan), was Governor of Mashhad 1587–1588, and of Hamadan 1591–1592. Married (1st) at Esfahan, 1601, Princess Fakhri-Jahan, daughter of Ismail II. Married (2nd) Del Aram, a Georgian. Married (3rd) Marta daughter of Eskandar Mirza. He had issue, two sons:

- Prince Shahzadeh Soltan Hasan Mirza (b. September 1588, Mazandaran – d. 18 August 1591, Qazvin)

- Prince Shahzadeh Soltan Hosein Mirza (b. 26 February 1591, Qazvin – d. before 1605)

- Prince Shahzadeh Tahmasph Mirza

- Prince Shahzadeh Soltan Mohammad Mirza (b. 18 March 1591, Qazvin – k. August 1632, Alamut, Qazvin) Blinded on the orders of his father, 1621.

- Prince Shahzadeh Soltan Ismail Mirza (b. 6 September 1601, Esfahan – k. 16 August 1613)

- Prince Shahzadeh Imam Qoli Amano'llah Mirza (b. 12 November 1602, Esfahan – k. August 1632, Alamut, Qazvin) Blinded on the orders of his father, 1627. He had issue, one son:

Daughters

- Princess Shahzadeh 'Alamiyan Shazdeh Beygom (d. before 1629), married Mirza Mohsen Razavi. She had issue, two sons.

- Princess Shahzadeh 'Alamiyan Zobeydeh Beygom (b. 4 December 1586 -k. 20 February 1632). She had issue, three sons and one daughter, including: Jahan-Banoo Begum, married in 1623, Simon II of Kartli son of Bagrat VII of Kartli by his wife, Queen Anna, daughter of Alexander II of Kakheti. She had issue, a daughter: Princess 'Izz-e-Sharif.

- Princess Shahzadeh 'Alamiyan Khan Agha Beygom, married Khalifa Sultan, son of Mirza Rafi al-Din Muhammad. She had issue, four sons and four daughters.

- Princess Shahzadeh 'Alamiyan Havva Beygom (d. 1617, Zanjan)

- Princess Shahzadeh 'Alamiyan Shahbanoo Beygom.

- Princess Shahzadeh ‘Alamiyan Malek-Nesa Beygom (d. 1629)

See also

- Battle of DimDim

- García de Silva Figueroa

- History of Iran

- Mausoleum of Shah Abbas I

- Persian embassy to Europe (1599–1602)

- Persian embassy to Europe (1609–1615)

- Safavid conversion of Iran from Sunnism to Shiism

Notes

- ↑ Ali Qoli Khan Shamlu, the governor of Herat, had originally been tasked with murder of Abbas by Shah Ishmail. Before he could act, the Shah had died, thus leaving him as governor, but without fulfilling his prerequisite task.[5]

- ↑ There is some confusion concerning the date which Abbas assumed power. The confusion sprouts from the fact that two distinctly different, but similar, occurrences both happened in the month of October, but in different years. First, Abbas seized power in the capital of Qazvin, whilst his father was leading the troops. This occurred on 16 October 1587. Then, after his father had returned, on 1 October 1588, Shah Mohammad abdicated and gave control of the empire over to Abbas in a ceremony.

Footnotes

- ↑ Thorne 1984, p. 1

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 71

- ↑ Newman 2006, p. 42

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 27

- ↑ Roemer 1986, p. 259

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 28

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 29

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 31–32

- ↑ Roemer 1986, p. 255

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 73

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 76

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 74

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 32–33

- ↑ Blow 2009, p. 29

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 35

- ↑ Dale 2010, p. 92

- ↑ Roemer 1986, p. 261

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 75

- ↑ Blow 2009, p. 30

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 36

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 37

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 38

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Newman 2006, p. 50

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 77

- ↑ Newman 2006, p. 52

- ↑ Roemer 1986, p. 266

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Roemer 1986, p. 265

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Haneda 1990, p. 818

- ↑ Haneda 1990, p. 819

- ↑ Dale 2010, p. 93

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Hoiberg 2010, p. 9

- ↑ Axworthy 2007, pp. 134–135

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Kremer 2013

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 79

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 141–142

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 143

- ↑ Starkey 2010, p. 38

- ↑ Madelung 1988, p. 390

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Matthee 1999.

- ↑ Roemer 1986, p. 267

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 84

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 147–148

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 85

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 148–149

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 149–150

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 150–151

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 87

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 153

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 154

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 155

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 156

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 157–158

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 158

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 158–159

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 120

- ↑ Eraly 2003, p. 263

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 121

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 123–124

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 124

- ↑ Eraly 2003, p. 264

- ↑ Parizi 2000, pp. 284–285.

- ↑ Babaie 2004, p. 94.

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 159

- ↑ Cole 1987, p. 186

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 161

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 162

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 96

- ↑ Dale 2010, p. 94

- ↑ Saslow 1999, p. 147

- ↑ Newman 2006, p. 69

- ↑ Sykes 1910, p. 318

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 96

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 98–99

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 111

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 107

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 103

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 209

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 104

- ↑ Jackson & Lockhart 1986, p. 454

- ↑ Kouymjian 2004, p. 20

- ↑ Khanbaghi 2006, p. 131

- ↑ Malekšāh Ḥosayn, p. 509

- ↑ Suny p. 50

- ↑ Asat'iani & Bendianachvili 1997, p. 188

- ↑ Lockhart 1953, p. 347

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 114

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 128

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 129

- ↑ Shakespeare 1863, pp. 258,262,282

- ↑ Wilson 2010, p. 210

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 131

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 134–135

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 136–137

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 161–162

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, p. 235

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 235–236

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 236–237

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 95

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 240–241

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 241–242

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 243–246

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 101

- ↑ Axworthy 2007, p. 134

- ↑ Roemer 1986, p. 278

- ↑ Savory 1980, p. 103

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 44–47

- ↑ Bomati & Nahavandi 1998, pp. 57–58

References

- Asat'iani, Nodar; Bendianachvili, Alexandre (1997). Histoire de la Géorgie (in French). Paris, France: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-7384-6186-7. LCCN 98159624.

- Axworthy, Michael (2007). Empire of the Mind: A History of Iran. London, UK: C. Hurst and Co. ISBN 1-8506-5871-4. LCCN 2008399438.

- Blow, David (2009). Shah Abbas: The Ruthless King Who became an Iranian Legend. London, UK: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84511-989-8. LCCN 2009464064.

- Bomati, Yves; Nahavandi, Houchang (1998). Shah Abbas, empereur de Perse 1587–1629 [Shah Abbas, Emperor of Persia, 1587-1629] (in French). Paris, France: Perrin. ISBN 2-2620-1131-1. LCCN 99161812.

- Parizi, Mohammad-Ebrahim Bastani (2000). "GANJ-ʿALĪ KHAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. X, Fasc. 3. pp. 284–285.

- Cole, Juan R. I. (May 1987). "Rival Empires of Trade and Imami Shi‘ism in Eastern Arabia, 1300–1800". International Journal of Middle East Studies (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press) 19 (2): 177–203. doi:10.1017/s0020743800031834. ISSN 0020-7438.

- Dale, Stephen F. (2010). The Muslim Empires of the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69142-0. LCCN 2010278301.

- Eraly, Abraham (2003) [2000 under the title Emperors of the Peacock Throne]. The Mughal Throne: The Saga of India's Great Emperors. London, UK: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. ISBN 1-8421-2723-3. LCCN 2005440260.

- Haneda, Masahi (1990). "Čarkas: ii. Under the Safavids". In Yarshater, Ehsan. Encyclopædia Iranica. IV: Bāyjū - Carpets : Fascicle 8: Cappadocia - Carpets XIV. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 818–819. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abbas I (Persia)". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-Ak - Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Jackson, Peter; Lockhart, Lawrence, eds. (1986). The Cambridge History of Iran. 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-5212-0094-6. LCCN 67012845.

- Khanbaghi, Aptin (2006). The Fire, the Star and the Cross: Minority Religions in Medieval and Early Modern Iran. London, UK: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-8451-1056-0. LCCN 2006296797.

- Kouymjian, Dickran (2004). "1: Armenia From the Fall of the Cilician Kingdom (1375) to the Forced Emigration under Shah Abbas (1604)". In Hovannisian, Richard G. The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 1-4039-6422-X. LCCN 2004273378.

- Kremer, William (25 January 2013). "Why Did Men Stop Wearing High Heels?". BBC News Magazine. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Lockhart, Lawrence (1953). Arberry, Arthur John, ed. The Legacy of Persia. The Legacy Series. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. LCCN 53002314.

- Madelung, W. (1988). "Baduspanids". In Yarshater, Ehsan. Encyclopaedia Iranica. III: Ātaš - Bayhaqī. pp. 385–391. ISBN 0-7100-9121-4. LCCN 84673402. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Newman, Andrew J. (2006). Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire. Library of Middle East History. London, UK: I. B.Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-667-0.

- Roemer, H. R. (1986). "5: The Safavid Period". In Jackson, Peter; Lockhart, Lawrence. The Cambridge History of Iran. 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-5212-0094-6. LCCN 67012845.

- Saslow, James M. (1999). "Asia and Islam: Ancient Cultures, Modern Conflicts". Pictures and Passions: A History of Homosexuality in the Visual Arts. New York, NY: Viking Adult. ISBN 0-6708-5953-2. LCCN 99019960.

- Savory, Roger (1980). Iran under the Safavids. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22483-7. LCCN 78073817.

- Shakespeare, William (1863). Clark, William George; Wright, William Aldis, eds. The Works of William Shakespeare III. Cambridge, UK: Macmillan and Company. LCCN 20000243.

- Starkey, Paul (2010). "Tawfīq Yūsuf Awwād (1911-1989)". In Allen, Roger. Essays in Arabic Literary Biography. 3: 1850-1950. Wiesbaden, Germany: Otto Harrassowitz GmbH & Co. ISBN 978-3-447-06141-4. ISSN 0938-9024. LCCN 2010359879.

- Sykes, Ella Constance (1910). Persia and its People. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company. LCCN 10001477.

- Matthee, Rudi (2011). Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–371. ISBN 0857731815.

- Babaie, Sussan (2004). Slaves of the Shah: New Elites of Safavid Iran. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–218. ISBN 9781860647215.

- Thorne, John, ed. (1984). "Abbas I". Chambers Biographical Dictionary. Edinburgh, UK: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltc. ISBN 0-550-18022-2.

- Matthee, Rudi (1999). "FARHĀD KHAN QARAMĀNLŪ, ROKN-AL-SALṬANA". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Mitchell, Colin P. (2009). The Practice of Politics in Safavid Iran: Power, Religion and Rhetoric. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–304. ISBN 0857715887.

- Wilson, Richard (March 2010). "When Golden Time Convents: Twelfth Night and Shakespeare's Eastern Promise" 6 (2). Routledge. pp. 209–226. doi:10.1080/17450911003790331. ISSN 1745-0918.

Additional reading

- Pearce, Francis Barrow (1920). Zanzibar, the Island Metropolis of Eastern Africa. New York, NY: E. P. Dutton and Company. LCCN 20008651. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Abbas I (Persia). |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abbas I of Persia. |

- Shah Abbās: The Remaking of Iran, The British Museum, in association with Iran Heritage Foundation, 19 February – 14 June 2009,

- John Wilson, Iranian treasures bound for Britain, BBC Radio 4, 19 January 2009, BBC Radio 4's live magazine, Front Row (audio report).

- "Shah 'Abbas: The Remaking of Iran"

| Abbas I of Persia Safavid Dynasty | ||

| Preceded by Mohammed Khodabanda |

Shahanshah of Persia 1 October 1588 – 19 January 1629 |

Succeeded by Safi |

| ||||||