Abacavir

| |

|

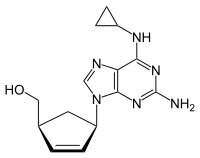

Chemical structure of abacavir | |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

| {(1S,4R)-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]cyclopent-2-en-1-yl}methanol | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Ziagen |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a699012 |

| |

| Oral (solution or tablets) | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 83% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Half-life | 1.54 ± 0.63 h |

| Excretion | Renal (1.2% abacavir, 30% 5'-carboxylic acid metabolite, 36% 5'-glucuronide metabolite, 15% unidentified minor metabolites). Fecal (16%) |

| Identifiers | |

|

136470-78-5 | |

| J05AF06 | |

| PubChem | CID 441300 |

| DrugBank |

DB01048 |

| ChemSpider |

390063 |

| UNII |

WR2TIP26VS |

| KEGG |

D07057 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:421707 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1380 |

| NIAID ChemDB | 028596 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C14H18N6O |

| 286.332 g/mol | |

|

SMILES

| |

| |

| Physical data | |

| Melting point | 165 °C (329 °F) |

| | |

Abacavir (ABC) ![]() i/ʌ.bæk.ʌ.vɪər/ is an antiretroviral used to treat HIV/AIDS. It is of the nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) type. Viral strains that are resistant to zidovudine (AZT) or lamivudine (3TC) are generally sensitive to abacavir (ABC), whereas some strains that are resistant to AZT and 3TC are not as sensitive to abacavir.

i/ʌ.bæk.ʌ.vɪər/ is an antiretroviral used to treat HIV/AIDS. It is of the nucleoside analog reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) type. Viral strains that are resistant to zidovudine (AZT) or lamivudine (3TC) are generally sensitive to abacavir (ABC), whereas some strains that are resistant to AZT and 3TC are not as sensitive to abacavir.

It is well tolerated: the main side effect is hypersensitivity, which can be severe, and in rare cases, fatal. Genetic testing can indicate whether an individual will be hypersensitive; over 90% of people can safely take abacavir.

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[1] It is available under the trade name Ziagen (ViiV Healthcare) and in the combination formulations Trizivir (abacavir, zidovudine and lamivudine) and Kivexa/Epzicom (abacavir and lamivudine).

_300mg.jpg)

Medical uses

Abacavir tablets and oral solution, in combination with other antiretroviral agents, are indicated for the treatment of HIV-1 infection.

Abacavir should always be used in combination with other antiretroviral agents. Abacavir should not be added as a single agent when antiretroviral regimens are changed due to loss of virologic response.

Side effects

Common reactions include nausea, headache, fatigue, vomiting, hypersensitivity reaction, diarrhea, fever/chills, depression, rash, anxiety, URI, ALT, AST elevated, hypertriglyceridemia, and lipodystrophy.[2]

Patients with liver disease should be cautious about using abacavir because of the possibility that it can aggravate the condition. The use of nucleoside drugs such as abacavir can very rarely cause lactic acidosis. Resistance to abacavir has developed in laboratory versions of HIV which are also resistant to other HIV-specific antiretrovirals such as lamivudine, didanosine and zalcitabine. HIV strains that are resistant to protease inhibitors are not likely to be resistant to abacavir.

Abacavir is contraindicated for use in infants under 3 months of age.

Little is known about the effects of Abacavir overdose. Overdose victims should be taken to a hospital emergency room for treatment.

Hypersensitivity syndrome

Hypersensitivity to abacavir is strongly associated with a specific allele at the human leukocyte antigen B locus namely HLA-B*57:01.[3][4] There is an association between the prevalence of HLA-B*5701 and ancestry. The prevalence of the allele is estimated to be 3.4 to 5.8% on average in populations of European ancestry, 17.6% in Indian Americans, 3.0% in Hispanic Americans, and 1.2% in Chinese Americans.[5][6] There is significant variability in the prevalence of HLA-B*5701 among African populations. In African Americans, the prevalence is estimated to be 1.0% on average, 0% in the Yoruba from Nigeria, 3.3% in the Luhya from Kenya, and 13.6% in the Masai from Kenya, although the average values are derived from highly variable frequencies within sample groups.[7]

Common symptoms of abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome include fever, malaise, nausea, and diarrhea; some patients may also develop a skin rash.[8] Symptoms of AHS typically manifest within six weeks of treatment using abacavir, although they may be confused with symptoms of HIV, immune restoration disease, hypersensitivity syndromes associated with other drugs, or infection.[9] The FDA released an alert concerning abacavir and abacavir-containing medications on July 24, 2008,[10] and the FDA-approved drug label for abacavir recommends pre-therapy screening for the HLA-B*5701 allele, and the use of alternative therapy in subjects with this allele.[11] Additionally, both the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC)[12] and Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG)[13] recommend use of an alternative therapy in individuals with the HLA-B*5701 allele.

Skin-patch testing may also be used to determine whether an individual will experience a hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir, although some patients susceptible to developing AHS may not react to the patch test.[14]

The development of suspected hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir requires immediate and permanent discontinuation of abacavir therapy in all patients, including patients who do not possess the HLA-B*5701 allele. On March 1, 2011, the FDA informed the public about an ongoing safety review of abacavir and a possible increased risk of heart attack associated with the drug. However, a meta-analysis of 26 studies conducted by the FDA did not find any association between abacavir use and heart attack [15][16]

Immunopathogenesis

The mechanism underlying abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome is related to the change in the HLA-B*5701 protein product. Abacavir binds with high specificity to the HLA-B*5701 protein, changing the shape and chemistry of the antigen-binding cleft. This results in a change in immunological tolerance and the subsequent activation of abacavir-specific cytotoxic T cells, which produce a systemic reaction known as abacavir hypersensitivity syndrome.[17]

Mechanism of action

ABC is an analog of guanosine (a purine). Its target is the viral reverse transcriptase enzyme.

Pharmacokinetics

Abacavir is given orally and has a high bioavailability (83%). It is metabolised primarily through alcohol dehydrogenase or glucuronyl transferase. It is capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier.

History

Abacavir was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on December 18, 1998 and is thus the fifteenth approved antiretroviral drug in the United States. Its patent expired in the United States on 2009-12-26.

Synthesis

References

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ https://online.epocrates.com/noFrame/showPage.do?method=drugs&MonographId=2043&ActiveSectionId=5

- ↑ Mallal, S., Phillips, E., Carosi, G. et al. (2008). "HLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavir". New England Journal of Medicine 358: 568–579. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0706135.

- ↑ Rauch, A., Nolan, D., Martin, A. et al. (2006). "Prospective genetic screening decreases the incidence of abacavir hypersensitivity reactions in the Western Australian HIV cohort study". Clinical Infectious Diseases 43: 99–102. doi:10.1086/504874.

- ↑ Heatherington et al. (2002). "Genetic variations in HLA-B region and hypersensitivity reactions to abacavir". Lancet 359: 1121–1122. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08158-8.

- ↑ Mallal et al. (2002). "Association between presence of HLA*B5701, HLA-DR7, and HLA-DQ3 and hypersensitivity to HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase inhibitor abacavir". Lancet 359: 727–732. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07873-x.

- ↑ Rotimi, C.N.; Jorde, L.B. (2010). "Ancestry and disease in the age of genomic medicine". New England Journal of Medicine 363: 1551–1558. doi:10.1056/nejmra0911564.

- ↑ Phillips, E., Mallal, S. (2009). "Successful translation of pharmacogenetics into the clinic". Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy 13: 1–9. doi:10.1007/bf03256308.

- ↑ Phillips, E., Mallal S. (2007). "Drug hypersensitivity in HIV". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology 7: 324–330. doi:10.1097/aci.0b013e32825ea68a.

- ↑ http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm123927.htm Accessed November 29, 2013.

- ↑ http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=ca73b519-015a-436d-aa3c-af53492825a1

- ↑ Martin MA, Hoffman JM, Freimuth RR et al. (May 2014). "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guidelines for HLA-B Genotype and Abacavir Dosing: 2014 update". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 95 (5): 499–500. doi:10.1038/clpt.2014.38. PMC 3994233. PMID 24561393.

- ↑ Swen JJ, Nijenhuis M, de Boer A et al. (May 2011). "Pharmacogenetics: from bench to byte--an update of guidelines". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 89 (5): 662–73. doi:10.1038/clpt.2011.34. PMID 21412232.

- ↑ Shear, N.H., Milpied, B., Bruynzeel, D.P. et al. (2008). "A review of drug patch testing and implications for HIV clinicians". AIDS 22: 999–1007. doi:10.1097/qad.0b013e3282f7cb60.

- ↑ http://www.drugs.com/fda/abacavir-ongoing-safety-review-possible-increased-risk-heart-attack-12914.html Accessed November 29, 2013.

- ↑ Ding X, Andraca-Carrera E, Cooper C et al. (December 2012). "No association of abacavir use with myocardial infarction: findings of an FDA meta-analysis". J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 61 (4): 441–7. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826f993c. PMID 22932321.

- ↑ Illing PT et al. 2012, Nature, doi:10.1038/nature11147

- ↑ Crimmins, M. T.; King, B. W. (1996). "An Efficient Asymmetric Approach to Carbocyclic Nucleosides: Asymmetric Synthesis of 1592U89, a Potent Inhibitor of HIV Reverse Transcriptase". The Journal of Organic Chemistry 61 (13): 4192. doi:10.1021/jo960708p.

External links

- Full Prescribing Information

- Abacavir pathway on PharmGKB

- Abacavir dosing guidelines from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC)

- Abacavir dosing guidelines from the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||