Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī

An imaginary rendition of Al Biruni on a 1973 Soviet post stamp | |

| Full name | Abū Rayḥān Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad Al-Birunī |

|---|---|

| Born |

4/5 September 973 Khwarezm, Samanid Empire (modern-day Uzbekistan) |

| Died |

13 December 1048 (aged 75) Ghazni, Ghaznavid Empire (modern-day Afghanistan) |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Region |

Khwarezm, Central Asia Ziyarid dynasty (Rey)[1] Ghaznavid dynasty (Ghazni)[2] |

Main interests | Physics, anthropology, comparative sociology, astronomy, astrology, chemistry, history, geography, mathematics, medicine, psychology, philosophy, theology |

Notable ideas | Founder of Indology, geodesy |

Major works | Ta'rikh al-Hind, The Mas'udi Canon, Understanding Astrology |

|

Influenced by

| |

|

Influenced

| |

Abū al-Rayhān Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Bīrūnī[n 1] (4/5 September 973 – 13 December 1048), known as Al-Biruni in English,[3] was a Persian[4][5][6] Muslim scholar and polymath from the Khwarezm region.

Al-Biruni is regarded as one of the greatest scholars of the medieval Islamic era and was well versed in physics, mathematics, astronomy, and natural sciences, and also distinguished himself as a historian, chronologist and linguist.[6] He was conversant in Khwarezmian, Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit, and also knew Greek, Hebrew and Syriac. He spent a large part of his life in Ghazni in modern-day Afghanistan, capital of the Ghaznavid dynasty which was based in what is now central-eastern Afghanistan. In 1017 he traveled to the Indian subcontinent and authored “Tarikh Al-Hind” (History of India) after exploring the Hindu faith practised in India. He is given the titles the "founder of Indology". He was an impartial writer on custom and creeds of various nations, and was given the title al-Ustadh ("The Master") for his remarkable description of early 11th-century India.[6] He also made contributions to Earth sciences, and is regarded as the "father of geodesy" for his important contributions to that field, along with his significant contributions to geography.

Life

He was born in the outer district of Kath, the capital of the Afrighid dynasty of Khwarezm[7] (or Chorasmia).[8] The word Biruni means "from the outer-district" in Persian, and so this became his nisba: "al-Bīrūnī" = "the Birunian".[8] His first twenty-five years were spent in Khwarezm where he studied Islamic jurisprudence, theology, grammar, mathematics, astronomy, medics and other sciences.[8] The Iranian Khwarezmian language, which was the language of Biruni,[9][10] survived for several centuries after Islam until the Turkification of the region, and so must some at least of the culture and lore of ancient Khwarezm, for it is hard to see the commanding figure of Biruni, a repository of so much knowledge, appearing in a cultural vacuum.[11]

He was sympathetic to the Afrighids, who were overthrown by the rival dynasty of Ma'munids in 995. Leaving his homeland, he left for Bukhara, then under the Samanid ruler Mansur II the son of Nuh. There he also corresponded with Avicenna[12] and there are extant exchanges of views between these two scholars.

In 998, he went to the court of the Ziyarid amir of Tabaristan, Shams al-Mo'ali Abol-hasan Ghaboos ibn Wushmgir. There he wrote his first important work, al-Athar al-Baqqiya 'an al-Qorun al-Khaliyya (literally: "The remaining traces of past centuries" and translated as "Chronology of ancient nations" or "Vestiges of the Past") on historical and scientific chronology, probably around 1000 A.D., though he later made some amendments to the book. He also visited the court of the Bavandid ruler Al-Marzuban. Accepting the definite demise of the Afrighids at the hands of the Ma'munids, he made peace with the latter who then ruled Khwarezm. Their court at Gorganj (also in Khwarezm) was gaining fame for its gathering of brilliant scientists.

In 1017, Mahmud of Ghazni took Rey. Most scholars, including al-Biruni, were taken to Ghazna, the capital of the Ghaznavid dynasty.[1] Biruni was made court astrologer[13] and accompanied Mahmud on his invasions into India, living there for a few years. Biruni became acquainted with all things related to India. He may even have learned some Sanskrit.[14] During this time he wrote the Kitab ta'rikh al-Hind, finishing it around 1030.[15]

Mathematics and astronomy

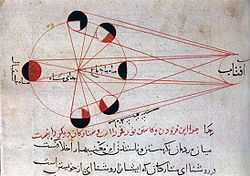

Ninety-five of 146 books known to have been written by Bīrūnī, were devoted to astronomy, mathematics, and related subjects like mathematical geography.[16] Biruni's major work on astrology[17] is primarily an astronomical and mathematical text, only the last chapter concerns astrological prognostication. His endorsement of astrology is limited, in so far as he condemns horary astrology[18] as 'sorcery'.

In discussing speculation by other Muslim writers on the possible motion of the Earth, Biruni acknowledged that he could neither prove nor disprove it, but commented favourably on the idea that the Earth rotates.[19] He wrote an extensive commentary on Indian astronomy in the Kitab ta'rikh al-Hind, in which he claims to have resolved the matter of Earth's rotation in a work on astronomy that is no longer extant, his Miftah-ilm-alhai'a (Key to Astronomy):

[T]he rotation of the earth does in no way impair the value of astronomy, as all appearances of an astronomic character can quite as well be explained according to this theory as to the other. There are, however, other reasons which make it impossible. This question is most difficult to solve. The most prominent of both modern and ancient astronomers have deeply studied the question of the moving of the earth, and tried to refute it. We, too, have composed a book on the subject called Miftah-ilm-alhai'a (Key to Astronomy), in which we think we have surpassed our predecessors, if not in the words, at all events in the matter.[20]

In his description of Sijzi's astrolabe's he hints at contemporary debates over the movement of the earth. He carried on a lengthy correspondence and sometimes heated debate with Ibn Sina, in which Biruni repeatedly attacks Aristotle's celestial physics: he argues by simple experiment that vacuum must exist;[21] he is "amazed" by the weakness of Aristotle's argument against elliptical orbits on the basis that they would create vacuum;[22] he attacks the immutability of the celestial spheres;[23] and so on.

In his major extant astronomical work, the Mas'ud Canon, Biruni utilizes his observational data to disprove Ptolemy's immobile solar apogee.[24] More recently, Biruni's eclipse data was used by Dunthorne in 1749 to help determine the acceleration of the moon[25] and his observational data has entered the larger astronomical historical record and is still used today[26] in geophysics and astronomy.

Physics

Al-Biruni contributed to the introduction of the experimental scientific method to mechanics, unified statics and dynamics into the science of mechanics, and combined the fields of hydrostatics with dynamics to create hydrodynamics.

Geography

Bīrūnī also devised his own method of determining the radius of the earth by means of the observation of the height of a mountain and carried it out at Nandana in Pind Dadan Khan (present-day Pakistan).[27]

Pharmacology and mineralogy

Due to an apparatus he constructed himself, he succeeded in determining the specific gravity of a certain number of metals and minerals with remarkable precision.[28]

History and chronology

Biruni's main essay on political history, Kitāb al-musāmara fī aḵbār Ḵᵛārazm (Book of nightly conversation concerning the affairs of Ḵᵛārazm) is now known only from quotations in Bayhaqī’s Tārīkh-e masʿūdī. In addition to this various discussions of historical events and methodology are found in connection with the lists of kings in his al-Āthār al-bāqiya and in the Qānūn as well as elsewhere in the Āthār, in India, and scattered throughout his other works.[29]

History of Religions

Bīrūnī is one of the most important Muslim authorities on the history of religion.[30] Al-Biruni was a pioneer in the study of comparative religion. He studied Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Hinduism, Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, and other religions. He treated religions objectively, striving to understand them on their own terms rather than trying to prove them wrong. His underlying concept was that all cultures are at least distant relatives of all other cultures because they are all human constructs. “What al-Biruni seems to be arguing is that there is a common human element in every culture that makes all cultures distant relatives, however foreign they might seem to one another.” (Rosenthal, 1976, p. 10). Al-Biruni was disgusted by scholars who failed to engage primary sources in their treatment of Hindu religion. He found existing sources on Hinduism to be both insufficient and dishonest. Guided by a sense of ethics and a desire to learn, he sought to explain the religious behavior of different groups.

Al-Biruni divides Hindus into an educated and an uneducated class. He describes the educated as monotheistic, believing that God is one, eternal, and omnipotent and eschewing all forms of idol worship. He recognizes that uneducated Hindus worshipped a multiplicity of idols yet points out that even some Muslims (such as the Jabiriyya) have adopted anthropomorphic concepts of God. (Ataman, 2005)

Indology

Bīrūnī’s fame as an Indologist rests primarily on two texts.[31] Al-Biruni wrote an encyclopedic work on India called “Tarikh Al-Hind” (History of India) in which he explored nearly every aspect of Indian life, including religion, history, geography, geology, science, and mathematics. He explores religion within a rich cultural context. He expresses his objective with simple eloquence: I shall not produce the arguments of our antagonists in order to refute such of them, as I believe to be in the wrong. My book is nothing but a simple historic record of facts. I shall place before the reader the theories of the Hindus exactly as they are, and I shall mention in connection with them similar theories of the Greeks in order to show the relationship existing between them.(1910, Vol. 1, p. 7;1958, p. 5)

An example of Al-Biruni’s analysis is his summary of why many Hindus hate Muslims. He explains that Hinduism and Islam are totally different from each other. Moreover, Hindus in 11th century India had suffered through waves of destructive attacks on many of its cities, and Islamic armies had taken numerous Hindu slaves to Persia which, claimed Al-Biruni, contributed to Hindus becoming suspicious of all foreigners, not just Muslims. Hindus considered Muslims violent and impure, and did not want to share anything with him. Over time, Al-Biruni won the welcome of Hindu scholars. Al-Biruni collected books and studied with these Hindu scholars to become fluent in Sanskrit, discover and translate into Arabic the mathematics, science, medicine, astronomy and other fields of arts as practiced in 11th century India. He was inspired by the arguments offered by Indian scholars who believed earth must be ellipsoid shape, with yet to be discovered continent at earth's south pole, and earth's rotation around the sun is the only way to fully explain the difference in daylight hours by latitude, seasons and earth's relative positions with moon and stars.[32] Al-Biruni was also critical of Indian scribes who he believed carelessly corrupted Indian documents while making copies of older documents.[33] Al-Biruni's translations as well as his own original contributions reached Europe in 12th and 13th century, where they were actively sought.

While others were killing each other over religious differences, Al-Biruni had a remarkable ability to engage Hindus in peaceful dialogue. Mohammad Yasin puts this dramatically when he says, “The Indica is like a magic island of quiet, impartial research in the midst of a world of clashing swords, burning towns, and burned temples.” (Indica is another name for Al-Biruni’s history of India). (Yasin, 1975, p. 212).

Works

Most of the works of Al-Biruni are in Arabic although he wrote one of his masterpieces, the Kitab al-Tafhim apparently in both Persian and Arabic, showing his mastery over both languages.[34] Bīrūnī’s catalogue of his own literary production up to his 65th lunar/63rd solar year (the end of 427/1036) lists 103 titles divided into 12 categories: astronomy, mathematical geography, mathematics, astrological aspects and transits, astronomical instruments, chronology, comets, an untitled category, astrology, anecdotes, religion, and books of which he no longer possesses copies.[35] His extant works include:

- Critical study of what India says, whether accepted by reason or refused (Arabic تحقيق ما للهند من مقولة معقولة في العقل أم مرذولة), also known as the Indica - a compendium of India's religion and philosophy

- The Book of Instruction in the Elements of the Art of Astrology (Kitab al-tafhim li-awa’il sina‘at al-tanjim).

- The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries (Arabic الآثار الباقية عن القرون الخالية) - a comparative study of calendars of different cultures and civilizations, interlaced with mathematical, astronomical, and historical information.

- The Mas'udi Canon (Persian قانون مسعودي) - an extensive encyclopedia on astronomy, geography, and engineering, named after Mas'ud, son of Mahmud of Ghazni, to whom he dedicated.

- Understanding Astrology (Arabic التفهيم لصناعة التنجيم) - a question and answer style book about mathematics and astronomy, in Arabic and Persian.

- Pharmacy - about drugs and medicines.

- Gems (Arabic الجماهر في معرفة الجواهر) about geology, minerals, and gems, dedicated to Mawdud son of Mas'ud.

- Astrolabe.

- A historical summary book.

- History of Mahmud of Ghazni and his father.

- History of Khawarezm.

Persian work

Although he preferred Arabic to Persian in scientific writing, his Persian version of the Al-Tafhim[34] is one of the most important of the early works of science in the Persian language, and is a rich source for Persian prose and lexicography.[34] The book covers the Quadrivium in a detailed and skilled fashion.[34]

Legacy

The crater Al-Biruni on the Moon is named after him.

In June 2009 Iran donated a scholar pavilion to United Nations Office in Vienna which is placed in the central Memorial Plaza of the Vienna International Center.[36] The Persian Scholars Pavilion at United Nations in Vienna, Austria is featuring the statues of four prominent Iranian figures. Highlighting the Iranian architectural features, the pavilion is adorned with Persian art forms and includes the statues of renowned Iranian scientists Avicenna, Abu Rayhan Biruni, Zakariya Razi (Rhazes) and Omar Khayyam.[37][38]

.jpg)

.jpg)

Notes and references

- Notes

- Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Exact Sciences, E.S.Kennedy, The Cambridge History of Iran: The period from the Arab invasion to the Saljuqs, Ed. Richard Nelson Frye, (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 394.

- ↑ Kemal Ataman, Understanding other religions: al-Biruni's and Gadamer's "fusion of horizons", (CRVP, 2008), 58.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, al-Biruni (Persian scholar and scientist) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia, Britannica.com, retrieved 2010-02-28

- ↑

- Bosworth, C. E. (1968), “The Political and Dynastic History of the Iranian World (A.D. 1000–1217)”, J.A. Boyle (ed.), Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods, Cambridge University Press: 1-202. [45]. Excerpt from page 7:"The Iranian scholar al-BIruni says that the Khwarazmian era began when the region was first settled and cultivated, this date being placed in the early 13th-century BC) "

- Richard Frye: "The contribution of Iranians to Islamic mathematics is overwhelming. ..The name of Abu Raihan Al-Biruni, from Khwarazm, must be mentioned since he was one of the greatest scientists in World History"(R.N. Frye, "The Golden age of Persia", 2000, Phoenix Press. pg 162)

- M. A. Saleem Khan, "Al-Biruni's discovery of India: an interpretative study", iAcademicBooks, 2001. pg 11: "It is generally accepted that he was Persian by origin, and spoke the Khwarizmian dialect"

- Rahman, H. U. (1995), A Chronology of Islamic History : 570 - 1000 CE, London: Mansell Publishing, p. 167, ISBN 1-897940-32-7,

A Persian by birth, Biruni produced his writings in Arabic, though he knew, besides Persian, no less than four other languages

- ↑

- Biruni (2007). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 April 2007;

- David C. Lindberg, Science in the Middle Ages, University of Chicago Press, p. 18:

"A Persian by birth, a rationalist in disposition, this contemporary of Avicenna and Alhazen not only studied history, philosophy, and geography in depth, but wrote one of the most comprehensive Muslim astronomical treatises, the Qanun Al-Masu'di."

;- L. Massignon, "Al-Biruni et la valuer internationale de la science arabe" in Al-Biruni Commemoration Volume, (Calcutta, 1951). pp 217-219.

;“ In a celebrated preface to the book of Drugs, Biruni says: And if it is true that in all nations one likes to adorn oneself by using the language to which one has remained loyal, having become accustomed to using it with friends and companions according to need, I must judge for myself that in my native Khwarezmian, science has as much as chance of becoming perpetuated as a camel has of facing Kaaba. ” - Gotthard Strohmaier, "Biruni" in Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach, Medieval Islamic Civilization: A-K, index: Vol. 1 of Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, 2006. excerpt from page 112: "Although his native Khwarezmian was also an Iranian language, he rejected the emerging neo-Persian literature of his time (Firdawsi), preferring Arabic instead as the only adequate medium of science.";

- D. N. MacKenzie, Encyclopaedia Iranica, "CHORASMIA iii. The Chorasmian Language". Excerpt: "Chorasmian, the original Iranian language of Chorasmia, is attested at two stages of its development..The earliest examples have been left by the great Chorasmian scholar Abū Rayḥān Bīrūnī.";

- A.L.Samian, "Al-Biruni" in Helaine Selin (ed.), "Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures ", Springer, 1997. excerpt from page 157: "his native language was the Khwarizmian dialect"

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 D.J. Boilot, "Al-Biruni (Beruni), Abu'l Rayhan Muhammad b. Ahmad", in Encyclopaedia of Islam (Leiden), New Ed., vol.1:1236-1238. Excerpt 1: "He was born of an Iranian family in 362/973 (according to al-Ghadanfar, on 3 Dhu'l-Hididja/ 4 September — see E. Sachau, Chronology, xivxvi), in the suburb (birun) of Kath, capital of Khwarizm". Excerpt 2:"was one of the greatest scholars of mediaeval Islam, and certainly the most original and profound. He was equally well versed in the mathematical, astronomic, physical and natural sciences and also distinguished himself as a geographer and historian, chronologist and linguist and as an impartial observer of customs and creeds. He is known as al-Ustdadh, "the Master".

- ↑ Al-Biruni, D.J. Boilet, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. I, ed. H.A.R. Gibb, J.H. Kramers, E. Levi-Provencal, J. Schacht, (Brill, 1986), 1236.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 C. Edmund Bosworth, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN i. Life" in Encyclopedia Iranica. Access date April 2011 at

- ↑ Gotthard Strohmaier, "Biruni" in Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach, Medieval Islamic Civilization: A-K, index: Vol. 1 of Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, 2006. excerpt from page 112: "Although his native Khwarezmian was also an Iranian language, he rejected the emerging neo-Persian literature of his time (Firdawsi), preferring Arabic instead as the only adequate medium of science.";

- ↑ D. N. MacKenzie, Encyclopaedia Iranica, "CHORASMIA iii. The Chorasmian Language" "Chorasmian, the original Iranian language of Chorasmia, is attested at two stages of its development..The earliest examples have been left by the great Chorasmian scholar Abū Rayḥān Bīrūnī.

- ↑ Bosworth, C.E. "Ḵh̲ W Ārazm." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2007. Brill Online. Accessed at 10 November 2007 <http://www.brillonline.nl/subscriber/entry?entry=islam_SIM-4205>

- ↑ Firoozeh Papan-Matin, Beyond death: the mystical teachings of ʻAyn al-Quḍāt al-Hamadhānī, (Brill, 2010), 111.

- ↑ Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization, Vol.3, (University of Chicago Press, 1958), 168.

- ↑ Jean Jacques Waardenburg, Muslim Perceptions of other Religions: A Historical Survey, (Oxford University Press, 1999), 27.

- ↑ Jean Jacques Waardenburg, 27.

- ↑ George Saliba, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN iii. Mathematics and Astronomy" in Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ Biruni, 'Book of Instruction in the Elements of the Art of Astrology', c.1027

- ↑ George C. Noonan, 'Classical Scientific Astrology'

- ↑ Douglas (1973, p.210)

- ↑ Al-Biruni, trans. by Edward C. Sachau (1888), Alberuni's India: an account of the religion, philosophy, and literature, p.277

- ↑ c.f. questions six and seven; Rafik Berjak, Muzaffar Iqbal 'Ibn Sinaal-Biruni correspondence pt.V', Islam and Science, Summer, 2005

- ↑ Rafik Berjak & Muzaffar Iqbal, 'Ibn SinaAl-Biruni correspondence pt.III', Islam & Science / Summer, 2004

- ↑ Rafik Berjak & Muzaffar Iqbal, 'Ibn SinaAl-Biruni correspondence pt.III', Islam & Science / Summer, 2003

- ↑ Rosenfeld, B. (1974), Review of Zhizn' i trudy Beruni, 'Biruni', Journal for the History of Astronomy, Vol. 5, p.135

- ↑ M. Th. Houtsma, 'E. J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936', p.681

- ↑ Francis Stephenson (1995), 'Historical eclipses and earth's rotation', pp.45,457,488-499

- ↑ David Pingree,"BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN iv. Geography" in Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ Georges C. Anawati, BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN v. Pharmacology and Mineralogy, in Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ David Pingree, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN vi. History and Chronology" in Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ François de Blois,"BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN vii. History of Religions" in Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ Bruce B. Lawerence, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN viii. Indology" in Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ Al Biruni's India (Columbia University Archives) (Biruni, 1910, Vol. 1, Chapter 26.); (Ataman, 2005).

- ↑ Al Biruni's India (Columbia University Archives) (Biruni, 1910, Vol. 1, p. 17); see also Vol 2 of Al-Biruni's India; (Ataman, 2005).

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 S.H. Nasr, "An introduction to Islamic cosmological doctrines: conceptions of nature and methods used for its study by the Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ, al-Bīrūnī, and Ibn Sīnā", 2nd edition, Revised. SUNY press, 1993. pp 111: "Al-Biruni wrote one of the masterpieces of medieval science, Kitab al-Tafhim, apparently in both Arabic and Persian, demonstrating how conversant he was in both tongues. The Kitab al-Tafhim is without doubt the most important of the early works of science in Persian and serves as a rich source for Persian prose and lexicography as well as for the knowledge of the Quadrivium whose subjects it covers in a masterly fashion"

- ↑ David Pingree, BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN ii. Bibliography, in Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ http://www.unis.unvienna.org/unis/pressrels/2009/unisvic167.html

- ↑ http://en.viennaun.mfa.ir/index.aspx?fkeyid=&siteid=207&pageid=28858

- ↑ http://parseed.ir/?ez=8002

- Bibliography

- C.E. Bosworth, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN i. Life" in Encyclopædia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- David Pingree, ""BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN ii. Bibliography", in Encyclopædia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- George Saliba, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN iii. Mathematics and Astronomy" in Encyclopædia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- David Pingree, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN iv. Geography" in Encycloapedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- Georges C. Anawati, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN v. Pharmacology and Mineralogy" in Encycloapedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- David Pingree, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN vi. History and Chronology" in Encyclpaedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- François de Blois, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN vii. History of Religions", in Encyclopædia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- Douglas, A. Vibert (1973), "Al-Biruni, Persian Scholar, 973-1048", Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 67: 209–211, Bibcode:1973JRASC..67..209D

- Bruce B. Lawerence, "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN viii. Indology", in Encyclopædia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- Yano, Michio (2007), "Bīrūnī: Abū al‐Rayḥān Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al‐Bīrūnī", in Thomas Hockey et al., The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, New York: Springer, pp. 131–3, ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0 | (PDF version)

- Kennedy, E. S. (2008) [1970-80], "Al-Bīrūnī (or Bērūnī), Abū Rayḥān (or Abu'l-Rayḥān) Muḥammad Ibn Aḥmad", Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Encyclopedia.com

- Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven John; Wallis, Faith (2005), Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-96930-1

- Abulfadl naba’I (1986), Calendar-making in the History, Astan Ghods Razavi Publishing Co

- Abolghassem Ghorbani; Markaze Nashre Daneshgahi (1995), Biruni Name, ISBN 964-01-0756-5

- Kiple, Kenneth F.; Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè (2001), The Cambridge World History of Food, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-40216-6

- Rashed, Roshdi; Morelon, Régis (1996), Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, 1 & 3, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-12410-7

- Saliba, George (1994), A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam, New York University Press, ISBN 0-8147-8023-7

- Dani, Ahmed Hasan (1973), Alberuni's Indica: A record of the cultural history of South Asia about AD 1030, University of Islamabad Press

- Samian, A.L. (2011), "Reason and Spirit in Al-Biruni’s Philosophy of Mathematics", in Tymieniecka, A-T., Reason, Spirit and the Sacral in the New Enlightenment, Islamic Philosophy and Occidental Phenomenology in Dialogue 5, Netherlands: Springer, pp. 137–146, doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9612-8_9, ISBN 978-90-481-9612-8

- Biruni, Abu al-Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al- (1910), E. Sachau, ed., Al-Beruni's India: an Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of Indiae, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

- Rosenthal, F. (1976), E. Yarshter, ed., Al-Biruni between Greece and India, New York: Iran Center, Columbia University

- Yasin, M. (1975), Al-Biruni in India, Islamic Culture

- Ataman, K. (2005), Re-Reading al-Biruni's India: a Case for Intercultural Understanding, Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations

Further reading

- On the Presumed Darwinism of Alberuni Eight Hundred Years before Darwin Jan Z. Wilczynski Isis Vol. 50, No. 4 (Dec., 1959), pp. 459–466 (article consists of 8 pages) Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society Stable URL:

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Abu Rayhan Biruni |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Abū-Rayhān Bīrūnī |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abu Rayhan al-Biruni. |

- BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN in Encyclopaedia Iranica

- C.E. Bosworth, BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN i. Life in Encyclopaedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- David Pingree, BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN ii. Bibliography in Encyclopaedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- George Saliba, BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN iii. Mathematics and Astronomy in Encyclopaedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- David Pingree, BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN iv. Geography in Encycloapedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- Georges C. Anawati, BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN v. Pharmacology and Mineralogy in Encycloapedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- Gomez, A. G. (2010) Biruni's Measurement of the Earth [online], http://www.academia.edu/8166456/Birunis_measurement_of_the_Earth

- Gomez, A. G. (2012) Biruni's Measurement of the Earth Geogebra interactive illustration.

- David Pingree, BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN vi. History and Chronology in Encyclpaedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- François de Blois, BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN vii. History of Religions in Encyclopaedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- Bruce B. Lawerence, BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN viii. Indology in Encyclopaedia Iranica (accessed April 2011)

- Richard Covington, Rediscovering Arabic Science, 2007, Saudi Aramco World

- "Al-Biruni (973-1048)." Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. 2001. Encyclopedia.com. 5 Feb. 2015.

- Al-Bīr Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography | 2008 | Copyright

- "Abu Rayhan al-Biruni." Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004. Encyclopedia.com. 5 Feb. 2015

Works of Al-Biruni online

- Hogendijk, Jan: The works of al-Bīrūnī – manuscripts, critical editions, translations and online links

- Elliot, H. M. (Henry Miers), Sir; John Dowson (1871), "1. Táríkhu-l Hind of Bírúní", The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period (Vol 2.), London : Trübner & Co. (At Packard Institute)

- Sachau, Dr.Edward C. (1910), ALBERUNI'S INDIA - An account of ... India about A.D. 1030 (Vol. 1), Kegan Paul, Trench Trubner & Co.Ltd., London

- Sachau, Dr.Edward C. (1910), ALBERUNI'S INDIA - An account of ... India about A.D. 1030 (Vol 2.), Kegan Paul, Trench Trubner & Co. Ltd., London

- Alberuni's India, in English

- "On Stones": Biruni's work on geology, medical properties of gemstones full text version + comments

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||