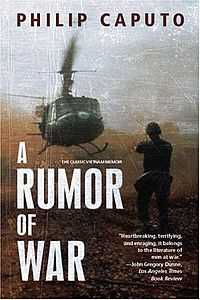

A Rumor of War

A Rumor of War is a 1977 memoir by Philip Caputo [1] about his service in the United States Marine Corps (USMC) in the early years of the Vietnam War.

Summary

In the foreword, the author states his purpose for writing this book. He makes clear this is not a history book, nor is it a historical accusation. The author states that his book is a story about war, based on a personal experience.

The book is divided into three parts. The first section, "The Splendid Little War", describes Lieutenant Philip Caputo's personal reasons for joining the USMC, the training that followed, and his eventual arrival to Vietnam. Lt. Caputo was a member of the 9th Expeditionary Brigade of the USMC, the first American regular troops unit sent to take part in the Vietnam War. He arrived on March 8, 1965, and his early experiences reminded him of the colonial wars portrayed by Rudyard Kipling. The 9th Expeditionary Brigade was deployed to Da Nang, formerly Tourane, on a "merely defensive" condition, primarily to set a perimeter around an airstrip that ensured arrival and departure of military goods and personnel. The first skirmishes against the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong made it clear to Lt. Caputo and his comrades that their earlier impression about Vietnam war as small and unimportant are all wrong.[2]

In the second part of the book, "The Officer in Charge of the Dead", Lt. Caputo is reassigned from his rifle company to a desk job documenting casualties. His new position in the Joint Staff of the brigade was a change that did not suit him, because he was proud of his rifle company duties and had a certain desire to return to basic infantry command. This distance from the Main Line of Resistance gave Lt. Caputo a different perspective of the conflict. Lt. Caputo described senior officers as being more worried about trivial matters than strategy. For example: movies being played in the open at night, risking potentially devastating mortar attacks. Lt. Caputo also witnessed enemy corpses being treasured as hunting trophies, and shown off to generals. He also describes American corpses carrying evidence of Viet Cong torture.

In the third part, "In Death's Grey Land," Lt. Caputo is reassigned to a rifle company. He describes the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong as fierce and skilled fighters and as having earned the grudging respect of American soldiers. Lt. Caputo describes his fellow Marines as having stopped wishing for epic, World War II-style battles; they had learned to detect boobytraps, to counter-snipe, and to comb the jungle in search of enemy bunkers and their rations. Lt. Caputo took part in these operations, until troops under his command miscarried orders and shot two suspects deliberately. Lt. Caputo assumed full responsibility for the incident and faced a court-martial. Eventually, he was relieved of his command and the charges were dropped.[3] Lt. Caputo was then reassigned to a training camp in North Carolina and eventually received an honorable discharge from the service.

In the Epilogue, almost ten years after the end of his tour of duty, Philip Caputo returned to Vietnam as a war journalist for a newspaper. Old memories of his war experiences and his comrades flood his mind as he witnesses the fall of Saigon to the troops of North Vietnam. Caputo left Vietnam on April 29, 1975.

A postscript published in 1996 details some of the anxieties Caputo experienced while writing the memoir, and the difficulties he had handling his fame and notoriety after its publication.

1980 TV Miniseries

Caputo's book was filmed as A Rumor of War at Camp Pendleton and Churubusco Studios, Mexico [4] with a cast featuring Brad Davis, Brian Dennehy, Keith Carradine, Michael O'Keefe, and Christopher Mitchum.

Praise For Book

“Caputo’s troubled, searching meditations on the love and hate of war, on fear, and the ambivalent discord warfare can create in the hearts of decent men, are among the most eloquent I have read in modern literature.”—William Styron, The New York Review of Books [5]

Sources

- Caputo, Philip. A Rumor of War. ISBN 003017631X OCLC 2974701

- Edition translated to Spanish: Caputo, Philip. Un Rumor de Guerra. Argos-Vergara. España. 1977, 1980. ISBN 84-7017-876-8

- Edition translated to Swedish: Caputo, Philip. Ett rykte om krig. Rabén & Sjögren, 1978, ISBN 91-29-51283-2

- Edition translated to German: Caputo, Philip. Stosstrupp durch die grüne Hölle.Bastei-Lübbe Band 11 360 1989, ISBN 3-404-11360-8

- Edition translated to Danish: Caputo, Philip. "Krigslarm", Gyldendal, 1978, ISBN 87-01-58621-1

References

- ↑ http://us.macmillan.com/author/philipcaputo

- ↑ http://becomingprince.blogspot.in/2012/02/book-review-rumor-of-war-by-philip.html#EarlyImpressions

- ↑ http://becomingprince.blogspot.in/2012/02/book-review-rumor-of-war-by-philip.html#CourtMartial

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0081443/

- ↑ http://us.macmillan.com/arumorofwar/PhilipCaputo