7th Cruiser Squadron (United Kingdom)

| 7th Cruiser Squadron | |

|---|---|

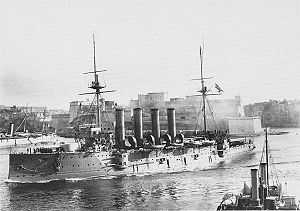

|

HMS Cressy, Lead ship of squadron | |

| Active | 1912-1914 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Allegiance | British Empire |

| Branch | Royal Navy |

| Size | 6 ships |

| Engagements | Action of 22 September 1914 |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Rear-Admiral Arthur Christian |

The 7th Cruiser Squadron was a blockading force of the Royal Navy during the First World War used to close the English Channel to German traffic. It was employed patrolling an area of the North Sea known as the "Broad Fourteens" in support of vessels guarding the northern entrance to the Channel. The Squadron had previously been part of the Third Fleet of the Home Fleets.

The squadron came to public attention when on 22 September 1914 three of the cruisers were sunk by one German submarine while on patrol. Approximately 1,450 sailors were killed and there was a public outcry at the losses. The incident eroded confidence in the government and damaged the reputation of the Royal Navy at a time when many countries were still considering which side they might support in the war.

Creation

The 7th Cruiser Squadron was created at the Nore as part of the reorganisation of the Royal Navy's home fleets which took effect on 1 May 1912. It formed part of the Third Fleet of the Home Fleets and effectively served as a reserve force stationed on the south coast of England. The squadron was composed mainly of the six Cressy-class armoured cruisers, which had been transferred from the 6th Cruiser Squadron of the former divisional structure of the Home Fleets, and already considered obsolescent despite being less than 12 years old.[1] Their status meant that most of the time they were manned by "nucleus crews" an innovation introduced by Admiral Jackie Fisher a few years earlier. Their ships' complements of 700 men plus officers were only brought up to full strength for manœvres or mobilisation. The nucleus crews were expected to keep the ships in a seaworthy condition the rest of the time.

The 1913 manœvres illustrate the system. In June, the command of squadrons was announced by the Admiralty. As a reserve formation, the 7th Cruiser Squadron had no flag officer until 10 June, when Rear-Admiral Gordon Moore — Third Sea Lord — was given the command upon taking leave from the Admiralty.[2] He hoisted his flag in Bacchante on 15 July.[3] All ships of the squadron would have been brought up to strength with men from other parts of the navy and from the Royal Naval Reserve. The manœvres took place and on 9 August Rear-Admiral Moore struck his flag and on the 16th the squadron was reduced back to reserve commission.[4]

First World War

Upon the outbreak of war with Germany in 1914, the Royal Navy's Second and Third Fleets were combined to form a Channel Fleet. The 7th Cruiser Squadron consisted of Cressy, Aboukir, Bacchante, Euryalus and Hogue. Their task was to patrol the relatively shallow waters of the Dogger Bank and the "Broad Fourteens" in the North Sea supported by destroyers of the Harwich Force.[5] The aim was to protect ships carrying supplies between Britain and France against German ships operating from the northern German naval ports.[6]

Although the cruisers had been designed for a speed of 21 kn (24 mph; 39 km/h), wear and tear meant they could now only manage 15 kn (17 mph; 28 km/h) at most and more typically only 12 kn (14 mph; 22 km/h). Bad weather sometimes meant that the smaller destroyers could not sail, and at such times the cruisers would patrol alone. A continuous patrol was maintained with some ships on station while others returned to harbour for coal and supplies.[7]

From 26-28 August 1914, the squadron was held in reserve during the operations which led to the Battle of Heligoland Bight.[8]

The "Live Bait Squadron"

On 21 August, Commodore Roger Keyes—commanding a submarine squadron also stationed at Harwich—wrote to his superior Admiral Sir Arthur Leveson warning that in his opinion the ships were at extreme risk of attack and sinking by German ships because of their age and inexperienced crews. The risk to the ships was so severe that they had earned the nickname "the live bait squadron" within the fleet. By 17 September, the note reached the attention of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill who met with Keyes and Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt—commander of a destroyer squadron operating from Harwich—while travelling to Scapa Flow to visit the Grand Fleet on 18 September. Churchill—in consultation with the First Sea Lord Prince Louis of Battenberg—agreed that the cruisers should be withdrawn and wrote a memo stating:

| “ | The Bacchantes[9] ought not to continue on this beat. The risks to such ships is not justified by any services they can render.[10] | ” |

Vice Admiral Frederick Sturdee—chief of the Admiralty war staff—objected that while the cruisers should be replaced no modern ships were available and the older vessels were the only ships that could be used during bad weather. It was therefore agreed between Battenberg and Sturdee to leave them on station until the arrival of new Arethusa-class cruisers then building.[11]

Sinking of three cruisers

At around 06:00 on 22 September, the three cruisers Aboukir, Cressy, and Hogue were steaming, alone, at 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h) in line ahead. The 7th Cruiser Squadron flagship, their sister ship Euryalus, as well as their light cruiser and destroyer screen, had been forced to temporarily return to base, leaving the three obsolete cruisers on their own.[12] They were spotted by the German submarine U-9, commanded by Lt. Otto Weddigen. They were not zigzagging, but all of the ships had lookouts posted to search for periscopes and one gun on each side of each ship was manned.

Weddigen ordered his submarine to submerge and closed the range with the unsuspecting British ships. At close range, he fired a single torpedo at Aboukir. The torpedo broke the back of Aboukir and she sank within 20 minutes with the loss of 527 men.

The captains of Cressy and Hogue thought Aboukir had struck a floating mine and came forward to assist her. Hogue hove to and began to pick up survivors. At this point, Weddigen fired two torpedoes into Hogue, mortally wounding her, but the submarine now surfaced and was fired upon.[12] As Hogue sank, the captain of Cressy, although now aware that the squadron was being attacked by a submarine, should have tried to flee; but this was not yet considered the proper response in such a situation.[12] Cressy consequently came to a stop amongst the survivors of her stricken sisters; Weddigen fired two more torpedoes into Cressy and sank her as well.

Dutch ships were nearby, and destroyers from Harwich were brought to the scene by distress signals; the brave intervention of two Dutch coasters and an English trawler prevented the loss from being even greater than it was.[12] The rescue vessels were able to save 837 men, but of the combined crews, 1,397 men and 62 officers were lost. A whole term (class) of Dartmouth naval cadets was aboard these ships, and many of the cadets were lost in the disaster.[12]

Repercussions

Otto Weddigen returned to Germany as the first naval hero of the war and was awarded the Iron Cross, Second and First Class. Each member of his crew received the Iron Cross, Second Class. The German achievement shook the reputation of the British navy throughout the world. Despite the age of Cressy-class vessels many Britons did not believe the sinking of three large armoured ships could have been the work of one lone submarine, but that other submarines and perhaps other non-British craft must have been involved. Both Admirals Beatty and Fisher spoke out against the folly of placing such ships where they had been. Churchill was widely blamed by the public for the disaster despite his memo of 18 September that the older ships should not be used in the venture.[13]

Rear-Admiral Arthur Christian was suspended on half pay; later, he was reinstated by Battenberg. Drummond was criticised for sailing in straight lines rather than zig-zagging to shake off submarines and for not requesting destroyer support as soon as the weather improved. Zig-zagging previously was not taken seriously by ships' captains who had not experienced submarine attacks; the tactic thereafter was made compulsory in enemy waters. Further, all major ships were instructed never to approach a ship severely disabled by mine or torpedo but to steam away and leave any rescue to smaller vessels.[14]

Three weeks later, the German war hero Weddigen—now operating U-9 off Aberdeen—torpedoed and sank Hawke, yet another British cruiser that was not zig-zagging in enemy waters. Weddigen himself was killed in March 1915 during a German raid in the Pentland Firth when his submarine—then U-29—was intentionally rammed by the battleship Dreadnought.

Aftermath

The remaining Cressy class ships were dispersed away from the British Isles. The remnants of the 7th Cruiser Squadron was reconstituted the following year as part of the Grand Fleet, which contained many better armoured and more modern ships than Bacchantes, but in 1916 the 7th was disbanded again. It did not see service at the Battle of Jutland.

Second World War

At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, the squadron was a unit within the Northern Patrol Force. The squadron was under the command of Vice Admiral Sir Max Horton, whose flagship was Effingham.

Notes

- ↑ Jane's Fighting Ships 1914. pp. p. 61.

- ↑ "The Naval Manœvres" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times (London). Tuesday, 10 June 1913. (40234), col B, p. 5.

- ↑ "Naval and Military Intelligence" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times (London). Friday, 4 July 1913. (40255), col C, p. 6.

- ↑ "Naval and Military Intelligence" (Official Appointments and Notices). The Times (London). Monday, 11 August 1913. (40287), col C, p. 13.

- ↑ Watts. The Royal Navy. pp. p. 91.

- ↑ 'Castles' p.128-129

- ↑ 'Castles' p. 129

- ↑ Osborne. Heligoland Bight. pp. p. 44.

- ↑ The class name given here is Baccante, and is reported thus in Massie, and Halpern. Janes gives Cressy class; Cressy was the first ship built

- ↑ Churchill. The World Crisis I. pp. p. 184.

- ↑ 'Castles' p. 129-130

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Archibald (1984). p. 197.

- ↑ 'Castles' p.137-138

- ↑ 'Castles' p.138-139

References

- Winston Churchill (2005). The World Crisis. Vol. I. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-8343-0.

- Jane, Fred T., ed. (1969). Jane's Fighting Ships 1914. New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc.

- Osborne, Eric W. (2006). The Battle of Heligoland Bight. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34742-4.

- Owen, David (2007). Anti-Submarine Warfare: An Illustrated History. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-014-5.

- Watts, Anthony John (1995). The Royal Navy: An Illustrated History. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-730-9.

- Robert Massie (2004). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. London: Johnathan Cape. ISBN 0-224-04092-8.

- Archibald, E.H.H.; illustrated by Ray Woodward (1984). The Fighting Ship of the Royal Navy, AD 897-1984 (Reprinted with minor revisions, 1987. ed.). London (reprint: New York): Blandford Press (reprint: Military Press [Dist. by Crown Publisher, Inc.]). p. 416. ISBN 0-517-63332-9.