2014 Atlantic hurricane season

| |

| Season summary map | |

| First system formed | July 1, 2014 |

|---|---|

| Last system dissipated | October 28, 2014 |

| Strongest storm | Gonzalo – 940 mbar (hPa) (27.77 inHg), 145 mph (230 km/h) |

| Total depressions | 9 |

| Total storms | 8 |

| Hurricanes | 6 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 18 direct, 3 indirect |

| Total damage | At least $262.8 million (2014 USD) |

| Atlantic hurricane seasons 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, Post-2015 | |

| Related article | |

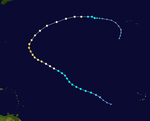

The 2014 Atlantic hurricane season was a near average Atlantic hurricane season that produced nine tropical cyclones, eight named storms, the fewest since the 1997 Atlantic hurricane season,[1] six hurricanes and two major hurricanes. It officially began on June 1, 2014 and ended on November 30, 2014. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The first storm of the season, Arthur, developed on July 1, one month after the official start; while the final storm, Hanna, dissipated on October 28.

Hurricane Arthur became the earliest known hurricane to make landfall in the state of North Carolina and was also the only system to make landfall in the United States this season. It developed from an initially non-tropical area of low pressure over the Southeastern United States and made landfall over Shackleford Banks on July 4 as a Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). The hurricane dissipated a few days later over the Labrador Sea. Arthur caused one indirect fatality and $52.5 million (2014 USD) in damage.

Other storms were notable in their own terms. Hurricane Bertha brushed the Lesser Antilles but its impacts were relatively minor. Hurricane Cristobal's rip currents affected the U.S. states of Maryland and New Jersey, resulting in one fatality in each state. Tropical storm Dolly made landfall in eastern Mexico and triggered flooding due to heavy rains. Hurricane Edouard became the first major hurricane of the season and the first to form in the North Atlantic basin since Sandy in 2012. Although Edouard never made landfall, two deaths near the coast of Maryland were attributed to strong rip currents from the storm. Hurricane Fay affected Bermuda, though its impacts were quite minimal.

Hurricane Gonzalo was the most intense hurricane of the season. A powerful Atlantic hurricane, Gonzalo had destructive impacts in the Lesser Antilles and Bermuda, and it was also the first Category 4 hurricane since Ophelia in 2011 and the strongest hurricane since Igor in 2010. It caused 5 direct fatalities and at least $200 million (2014 USD) in damage. The last storm of the season, Tropical Storm Hanna, made landfall over Central America in late October producing minimal impact.

Most major forecasting agencies predicted below-average activity to occur this season due to a strong El Niño that was expected to hinder high seasonal activity; however, the El Niño failed to materialize.[2]

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named | Hurricanes | Major | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (1981–2010) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | [3] | |

| Record high activity | 28 | 15 | 7 | [4] | |

| Record low activity | 4 | 2† | 0† | [4] | |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| TSR | December 12, 2013 | 14 | 6 | 3 | [5] |

| WSI | March 24, 2014 | 11 | 5 | 2 | [2] |

| TSR | April 7, 2014 | 12 | 5 | 2 | [6] |

| CSU | April 10, 2014 | 9 | 3 | 1 | [7] |

| NCSU | April 16, 2014 | 8–11 | 4–6 | 1–3 | [8] |

| UKMET | May 16, 2014 | 10* | 6* | N/A | [9] |

| NOAA | May 22, 2014 | 8–13 | 3–6 | 1–2 | [10] |

| FSU COAPS | May 29, 2014 | 5–9 | 2–6 | 1–2 | [11] |

| CSU | July 31, 2014 | 10 | 4 | 1 | [12] |

| TSR | August 5, 2014 | 9–15 | 4–8 | 1–3 | [13] |

| NOAA | August 7, 2014 | 7–12 | 3–6 | 0–2 | [14] |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| Actual activity |

8 | 6 | 2 | ||

| * June–November only † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

Forecasts of hurricane activity are issued before each hurricane season by noted hurricane experts Philip J. Klotzbach, William M. Gray, and their associates at Colorado State University (CSU); and separately by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) forecasters.

Klotzbach's team (formerly led by Gray) defined the average number of storms per season (1981 to 2010) as 12.1 tropical storms, 6.4 hurricanes, 2.7 major hurricanes (storms reaching at least Category 3 strength on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale), and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index of 96.1.[15] NOAA defines a season as above-normal, near-normal or below-normal by a combination of the number of named storms, the number reaching hurricane strength, the number reaching major hurricane strength, and the ACE index.[16]

Pre-season forecasts

On December 13, 2013, Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), a public consortium consisting of experts on insurance, risk management, and seasonal climate forecasting at University College London, issued their first outlook on seasonal hurricane activity during the 2014 season. In their report, the organization called for a near-normal year, with 14 (±4) tropical storms, 6 (±3) hurricanes, 3 (±2) intense hurricanes, and a cumulative ACE index of 106 (±58) units. The basis for such included slightly stronger than normal trade winds and slightly warmer than normal sea surface temperatures across the Caribbean Sea and tropical North Atlantic.[5] A few months later, on March 24, 2014, Weather Services International (WSI), a subsidiary company of The Weather Channel, released their first outlook, calling for 11 named storms, 5 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes. Two factors—cooler-than-average waters in the eastern Atlantic, and the likelihood of an El Niño developing during the summer of 2014—were expected to negate high seasonal activity.[2]

On April 7, TSR issued their second extended-range forecast for the season, lowering the predicted numbers to 12 (±4) named storms, 5 (±3) hurricanes, 2 (±2) major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 75 (±57) units.[6] Three days later, CSU issued their first outlook for the year, predicting activity below the 1981–2010 average. Citing a likely El Niño of at least moderate intensity and cooler-than-average tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures, the organization predicted 9 named storms, 3 hurricanes, 1 major hurricane, and an ACE index of 55 units. The probability of a major hurricane making landfall on the United States or tracking through the Caribbean Sea was expected to be lower than average.[7]

On May 16, the United Kingdom Met Office (UKMO) issued a forecast of a slightly below-average season. It predicted 10 named storms with a 70% chance that the number would be between 7 and 13 and 6 hurricanes with a 70% chance that the number would be between 3 and 9. It also predicted an ACE index of 84 with a 70% chance that the index would be in the range 47 to 121.[9]

Seasonal summary

The season's first tropical cyclone, Arthur, developed on July 1, ahead of the long-term climatological average of July 9. Early on July 3, the system intensified into a hurricane, preceding the climatological average of August 10.[17] After continuing to steadily intensify, it moved ashore between Cape Lookout and Cape Hatteras as a Category 2 hurricane, becoming the first U.S. landfalling cyclone of that intensity since Hurricane Ike in 2008.[18] Upon moving inland, Arthur became the earliest known hurricane to strike the North Carolina coastline on record.[19]

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index for the season was 66.725 units.[nb 1]

Storms

| | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hurricane Arthur

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 1 – July 5 | ||

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 973 mbar (hPa) | ||

On June 27, a non-tropical area of low pressure, whose potential genesis was first discussed by the National Hurricane Center (NHC) two days prior,[20] formed over South Carolina and moved into the southwestern Atlantic the next day.[21][22] Amid a generally conducive environment, the low steadily organized and gained tropical characteristics; in conjunction with satellite imagery and radar data, it was upgraded to a tropical depression at 03:00 UTC on July 1.[23] The depression was further upgraded to Tropical Storm Arthur nine hours later based on surface observations from Grand Bahama.[24] Steered northward in advance of a strong upper-level trough, the overall appearance of Arthur improved despite dry mid- to upper-level dry air. Data from two Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunter aircraft indicated the cyclone attained Category 1 hurricane intensity at 0900 UTC on July 3 and further intensified to reach Category 2 strength at 0100 UTC the next day.[25][26] After making landfall near Cape Lookout, North Carolina,[27] the storm accelerated northeastward while losing tropical characteristics; at 1200 UTC on July 5, the NHC declared Arthur as extratropical.[28]

As a developing tropical cyclone, Arthur produced minor rainfall across the northwestern Bahamas.[29][30] A dozen swimmers required rescuing as a result of strong rip currents off the coastline of Florida.[31] Upon striking North Carolina on July 3, Arthur became the earliest known hurricane on record to make landfall there.[32] Maximum sustained winds peaked at 77 mph (124 km/h), with a peak gust of 101 mph (163 km/h), at Cape Lookout,[27] and Oregon Inlet recorded a peak storm surge of 4.5 ft (1.4 m).[33] At its height, Arthur knocked out power to 44,000 people across the state, triggering Duke Energy to deploy over 500 personnel to restore electricity.[34] Widespread rainfall totals of 6–8 in (150–200 mm) led to the inundation of numerous buildings in Manteo.[35] As the storm passed offshore New England, sustained winds of 47 mph (63 km/h) and gusts up to 63 mph (101 km/h) were observed. Observed rainfall totals over a half foot required the issuance of a flash flood emergency for New Bedford, Massachusetts, while several roads were shut down in surrounding locations.[36] After transitioning into an extratropical cyclone, Arthur knocked out power to more than 290,000 individuals across the Maritimes,[37] with damage to the electrical grid considered the worst since Hurricane Juan in Nova Scotia.[38] Hurricane-force gusts were observed in Nova Scotia, with tropical storm-force winds observed as far away as Quebec.[37]

Tropical Depression Two

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 21 – July 23 | ||

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1012 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa on July 17. Steered westward, a small area of low pressure developed in association with the wave two days later. Convection steadily increased and organized, leading to the formation of a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on July 21. The depression failed to intensify into a tropical storm amid an exceptionally dry and stable environment and instead degenerated into a trough by 18:00 UTC on July 23 while located east of the Lesser Antilles.[39]

Hurricane Bertha

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 1 – August 6 | ||

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 998 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa on July 24. Initially devoid of appreciable convection due to dry air and wind shear, shower and thunderstorm activity increased four days later in the wake of a convectively-coupled kelvin wave, resulting in the formation of an area of low pressure. Following a reprieve in upper-level winds, the wave acquired sufficient organization to be declared Tropical Storm Bertha at 00:00 UTC on August 1. Steered west to west-northwest around a large mid-level ridge in the southwestern Atlantic, the newly designated cyclone failed to organize as shear once again intensified, and Bertha briefly lost its closed circulation south of Puerto Rico on August 2. After passing northeast of the southeastern Bahamas, a track over warm waters and into an increasingly moist environment allowed the system to organize, and Bertha was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane early on August 4. The system attained peak winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) that day before succumbing to unfavorable upper-level winds imparted by an approaching trough. At 18:00 UTC on August 6, Bertha transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while positioned south-southeast of Nova Scotia. The cyclone gradually spun down and degenerated into a trough southwest of Ireland several days later.[40] The remnants of Hurricane Bertha affected the United Kingdom between August 9 and August 11, as it experienced its coolest August since 1993.

Hurricane Cristobal

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 23 – August 29 | ||

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 965 mbar (hPa) | ||

A strong tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Four while located near Turks and Caicos Islands on August 23.[41] The system intensified into Tropical Storm Cristobal while moving northwestward on the following day. However, Cristobal soon decelerated and moved erratically due to an upper-level trough. Despite being continually plagued by wind shear, the storm managed to reach Category 1 hurricane intensity early on August 25.[42] Around that time, a trough of low pressure decreased wind shear and caused Cristobal to begin accelerating in a generally northward motion. By early on August 27, the hurricane curved northeastward, allowing it to remain well offshore the East Coast of the United States and pass far northwest of Bermuda. After maintaining an overall disheveled appearance for much of its duration, the storm began developing a concentrated area of deep convection near its center on August 28. Early the following day, Cristobal attained its peak intensity as a moderate Category 1 hurricane with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). However, the storm soon began losing tropical characteristics and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while located well southeast of Newfoundland on August 29. During the next several days, Cristobal's remnants continued moving northeastwards, crossing over Iceland at the end of August. On September 2, 2014, Cristobal's remnants were absorbed by another extratropical cyclone to the north of Iceland.[43]

Upon the development of the storm, several tropical storm warnings became effective in the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands. The precursor of Cristobal and the storm itself dropped heavy precipitation on Puerto Rico, with 13.21 in (336 mm) of rain observed in the municipality of Tibes, bring drought relief to the island. The storm downed many trees and power lines and left more than 23,500 people without power and 8,720 without water. In Dominican Republic, large amounts of rainfall left several communities isolated, flooded at least 158 homes, and killed two people. Thousands of people were evacuated from their homes. In Haiti, mudslides and flooding rendered 640 families homeless and destroyed or severely damaged at least 34 homes. Two people who went missing were later presumed to have drowned. In the Turks and Caicos Islands, the erratically-moving Cristobal produced up to 12 in (300 mm) of precipitation on various islands. The international airport on Providenciales briefly closed due to flooding, where one drowning death occurred. Portions of North Caicos were inundated with up to 5 ft (1.5 m) of water. Heavy rainfall also fell in the Bahamas.[44] Along the East Coast of the United States, rip currents resulted in one death each in Maryland and New Jersey.

Tropical Storm Dolly

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 1 – September 3 | ||

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave crossing the Yucatán Peninsula quickly strengthened after entering the Bay of Campeche, and was designated Tropical Depression Five at 21:00 UTC on September 1.[45] Data from an Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunters reconnaissance flight indicated that the tropical depression had strengthened into Tropical Storm Dolly at 06:00 UTC on September 2.[46] Tropical Storm Dolly made landfall near Tampico, Mexico at 03:00 UTC on September 3.[47] At 15:00 UTC on September 3, Dolly dissipated after losing its well defined center of circulation over Eastern Mexico.[48] The circulation of Hurricane Norbert sent Dolly's remnants over the southwestern United States, resulting in flooding.

Heavy rains from the storm triggered flooding that temporarily isolated three communities in Tampico. One fatality was attributed to the storm. The hardest hit area was Cabo Rojo where 210 homes were affected, 80 of which sustained damage.[49] Total losses to the road network in Tamaulipas reached 80 million pesos (US$6 million).[50] Structural damage amounted to 7 million pesos (US$500,000).[51]

Hurricane Edouard

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 11 – September 19 | ||

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min) 955 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave moved off the western coast of Africa on September 6. Accompanied by a broad area of low pressure, the disturbance slowly developed, acquiring sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on September 11 while located west of the Cape Verde Islands; twelve hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Edouard. The newly formed cyclone moved northwest following designation, steered around a subtropical ridge across the central and eastern Atlantic. Despite a drier than normal atmosphere, warm sea surface temperatures and low wind shear favored steady intensification, and Edouard became a Category 1 hurricane by 12:00 UTC on September 14. With a well-defined eye surrounded by intense eyewall convection, Edouard further strengthened into a major hurricane early on September 16, attaining peak winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) at 12:00 UTC, the first major hurricane in the Atlantic since Hurricane Sandy on October 25, 2012. The cyclone began an abrupt weakening trend thereafter, likely a result of an eyewall replacement cycle and cold water upwelling, as it curved northward and eventually northeast in advance of an upper-level trough. Edouard weakened below hurricane intensity by 00:00 UTC on September 19 and degenerated into a remnant low eighteen hours later. The remnant low moved southeastward and then southward, until it merged with a frontal zone well south-southwest of the Azores on September 21.[52]

Though Edouard remained well away from land throughout its existence, large swells and dangerous rip currents affected much of the East Coast of the United States. Rip current warnings were issued on September 17 for Duval, Flagler, Nassau, and St. Johns counties in Florida and Camden and Glynn counties in Georgia.[53] Waves in the area were forecast to reach 3 to 4 ft (0.91 to 1.22 m).[54] On September 17, two men drowned off the coast of Ocean City, Maryland, due to strong rip currents.[55] The Bermuda Weather Service noted the hurricane as a "potential threat"; however, Edouard remained several hundred miles away from the islands.[56]

On September 16, several unmanned drones designed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration were launched by Hurricane Hunter aircraft while investigating Edouard. This marked the first time that drones were used in such a manner by NOAA. Unlike the manned aircraft, the drones were able to fly to the lower-levels of hurricanes and investigate the more dangerous areas near the surface.[57] Additionally, a NASA-operated Global Hawk flew into the storm, equipped with two experimental instruments: the Scanning High-resolution Interferometer Sounder (S-HIS) and Cloud Physics Lidar (CPL). The S-HIS provided measurements of temperature and relative humidity while the CPL was for studying aerosols and the structure of cloud layers within hurricanes.[58]

Hurricane Fay

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 10 – October 13 | ||

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 983 mbar (hPa) | ||

A broad weather disturbance was situated several hundred miles northeast of the Lesser Antilles on October 8. After the development of a well-defined circulation and convective rainbands to the north and west, it was determined that Subtropical Storm Fay formed about 615 miles (990 km) south of Bermuda at 06:00 UTC on October 10. The storm gradually attained tropical characteristics as it turned north, transitioning into a tropical storm early on October 11. Despite being plagued by strong disruptive wind shear for most of its duration, Tropical Storm Fay significantly intensified. Veering toward the east, Fay briefly intensified into a Category 1 hurricane while making landfall on Bermuda early on October 12. Wind shear eventually took its toll on Fay, causing the hurricane to weaken to a tropical storm later that day and degenerate into an open trough early on October 13.[59]

A few tropical cyclone warnings and watches were issued in anticipation of Fay's impact on Bermuda.[59] Public schools were closed in advance of the storm.[60] Despite its modest strength, Fay produced relatively extensive damage on Bermuda. Winds gusting over 80 mph (130 km/h) clogged roadways with downed trees and power poles, and left a majority of the island's electricity customers without power. The terminal building at L.F. Wade International Airport was severely flooded after the storm compromised its roof and sprinkler system.[59] Immediately after the storm, 200 Bermuda Regiment soldiers were called to clear debris and assist in initial damage repairs.[61] Cleanup efforts overlapped with preparations for the approach of the stronger Hurricane Gonzalo. There were concerns that debris from Fay could become airborne during Gonzalo and exacerbate future destruction.[62] Overall, it is estimated that the hurricane left at least $3.8 million (2014 USD) in damage.[59]

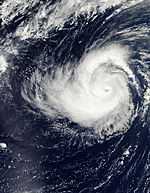

Hurricane Gonzalo

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 12 – October 19 | ||

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min) 940 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical depression formed about 390 mi (630 km) east of the Leeward Islands by 00:00 UTC on October 12 from a tropical wave that emerged off Africa on October 4. Twelve hours later, it intensified into Tropical Storm Gonzalo. Steered west and eventually west-northwest, the cyclone rapidly intensified amid favorable atmospheric dynamics, becoming a minimal hurricane by 12:00 UTC on October 13. After curving northwest and emerging into the southwestern Atlantic, Gonzalo continued its period of rapid intensification, becoming a major hurricane by 18:00 UTC on October 14 and a Category 4 hurricane six hours later. The hurricane underwent an eyewall replacement cycle the next day, but ultimately attained peak winds of 145 mph (230 km/h) by 12:00 UTC on October 16. Late that afternoon, the effects of a second eyewall replacement cycle, cooler waters, and increased shear caused the storm to begin a steady weakening trend as it accelerated north-northeast ahead of an approaching trough. Gonzalo weakened below major hurricane intensity by 00:00 UTC on October 18 and made landfall on Bermuda with winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) six hours later. The cyclone continued north-northeast, transitioning into an extratropical cyclone by 18:00 UTC on October 19 while located roughly 460 mi (740 km) northeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The extratropical cyclone turned east-northeast and was absorbed by a cold front early on October 20.[63]

Widespread impact was observed across the northeastern Caribbean Sea as Gonzalo moved through the region. Sustained winds of 67 mph (103 km/h), with gusts to 88 mph (142 km/h), were observed on Antigua,[64] where downed trees blocked roads and damaged houses. Numerous fishing boats were destroyed and the island was subject to a widespread power outage.[65] On Saint Martin, 37 docked boats were destroyed and the airport recorded sustained winds of 55 mph (88 km/h) with gusts to 94 mph (151 km/h).[66][67] As Gonzalo made landfall on Bermuda, L.F. Wade International Airport recorded sustained winds of 93 mph (150 km/h) and gusts up to 113 mph (181 km/h); an elevated observing station at St. Davids reported a peak gust of 144 mph (232 km/h).[68] At the height of the storm, 31,000 out of 36,000, or 86%, of electricity customers on the island lost power.[69] Multiple buildings suffered roof damage, and downed trees and power lines prevented travel across the island.[70] After transitioning into an extratropical cyclone, Gonzalo delivered strong winds to Newfoundland, with gusts peaking at 66 mph (106 km/h) at Cape Pine.[71] Approximately 100 households lost power, while heavy rain caused localized urban flooding in St. Johns.[72] Upon reaching the United Kingdom on October 21, heavy rain and strong winds, with gusts reaching 70 mph (100 km/h) in Wales, downed trees and disrupted transportation.[73] In central Europe, Stuttgart recorded peak gusts of 76 mph (122 km/h),[74] while snow fell across the Alps.[75] On October 24, the remnants of Gonzalo impacted southern Greece, producing about 5.9 in (150 mm) in just two hours; about 300 cars were swept away in associated flooding.[76] In total, Gonzalo caused five deaths.[63]

Tropical Storm Hanna

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 22 – October 28 | ||

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) | ||

On October 19, the remnants of Tropical Storm Trudy emerged over the Bay of Campeche after losing its low-level circulation over the mountainous terrain of Mexico. Moving slowly eastward, the system redeveloped a new surface circulation on October 21; however, it lacked organized deep convection and was not classified as a tropical depression at that time. It was not until 00:00 UTC on October 22 that shower and thunderstorm activity was deemed sufficient to warrant the designation of Tropical Depression Nine. At that time, the system was situated 175 mi (280 km) west of Campeche, Mexico. Reconnaissance aircraft investigating the depression measured a central pressure of 1000 mbar (hPa; 29.53 inHg) upon its formation, the lowest in relation to the cyclone throughout its existence. Increasing wind shear and dry air intrusion soon weakened the depression and it degraded into a remnant low early on October 23 before making landfall along the southwestern coast of the Yucatán Peninsula. After crossing the southern Yucatán and northern Belize, the low emerged over the northwestern Caribbean Sea on October 24. Hostile environmental conditions imparted by a nearby frontal boundary inhibited development ultimately caused the system to degrade into a trough and become entangled within the front.[77]

Subsequent weakening of the frontal system on October 26 allowed the depression's remnants to become better defined as they moved southeast and later southward. The system regained a closed circulation by 12:00 UTC that day as it began turning west. Following the development of deep convection the system regenerated into a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on October 27 while situated roughly 80 mi (130 km) east of the Nicaragua–Honduras border. ASCAT scatterometer data shortly thereafter revealed wind vectors of 35–40 mph (55–65 km/h), resulting in the depression being upgraded to Tropical Storm Hanna at 06:00 UTC. Just ten hours later Hanna made landfall over extreme northeastern Nicaragua and quickly weakened back to a depression. The system once again degraded to a remnant low early on October 28 before turning northwestward and emerging over the Gulf of Honduras. Some signs of redevelopment presented themselves once more throughout the day, but the remnants of Hanna soon moved inland over Belize early on October 29. The system finally dissipated over northwest Guatemala on the following day.[77]

Storm names

The following names were used to name storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2014. This is the same list used in the 2008 season, except for Gonzalo, Isaias, and Paulette, which replaced Gustav, Ike, and Paloma, respectively. The name Gonzalo was used for the first time in 2014. There were no names retired this year; thus, the same list will be used again in the 2020 season.[78]

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms that have formed during the 2014 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, areas affected, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 2014 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (millions USD) |

Deaths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthur | July 1 – July 5 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 973 | The Bahamas, United States East Coast, Atlantic Canada | 52.5 | 0 (1)[79] | |||

| Two | July 21 – July 23 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1012 | None | None | None | |||

| Bertha | August 1 – August 6 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 998 | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles, Turks and Caicos Islands, The Bahamas, United States East Coast, Western Europe | Minimal | 3 (1)[80] | |||

| Cristobal | August 23 – August 29 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 965 | Greater Antilles, Turks and Caicos Islands, The Bahamas, Bermuda, United States East Coast, Iceland | Unknown | 7[81] | |||

| Dolly | September 1 – September 3 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | Mexico, Texas | 6.5 | 1 | |||

| Edouard | September 11 – September 19 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | 955 | United States East Coast | Minor | 2 | |||

| Fay | October 10 – October 13 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 983 | Bermuda | 3.8 | None | |||

| Gonzalo | October 12 – October 19 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 940 | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada, Europe | 200 | 5 (1)[63] | |||

| Hanna | October 22 – October 28 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1000 | Mexico, Central America | Unknown | None | |||

| Season Aggregates | ||||||||||

| 9 cyclones | July 1 – October 28 | 145 (230) | 940 | 262.8 | 18 (3) | |||||

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2014 Atlantic hurricane season. |

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- 2014 Pacific hurricane season

- 2014 Pacific typhoon season

- 2014 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2013–14, 2014–15

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2013–14, 2014–15

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2013–14, 2014–15

Notes

- ↑ The totals represent the sum of the squares for every tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph, 61 km/h), divided by 10,000. Calculations are provided at Talk:2014 Atlantic hurricane season/ACE calcs.

References

- ↑ Brian K Sullivan (November 25, 2014). "Snowy End to Hurricane Season That Many Never Noticed". Bloomberg Business. Bloomberg Business. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jon Erdman (March 24, 2014). "2014 Hurricane Season Outlook: Another Quiet Season Possible for Atlantic". Weather Services International. The Weather Channel. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (March 2, 2015). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (December 12, 2013). "Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2014" (PDF). University College London. Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (April 7, 2014). "April Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2014" (PDF). University College London. Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Phillip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (April 10, 2014). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2014" (PDF). Colorado State University. Colorado State University. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- ↑ Lian Xie (April 16, 2014). "Expect Relatively Quiet Hurricane Season, NC State Researchers Say". North Carolina State University. North Carolina State University. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 North Atlantic Tropical Storm Seasonal Forecast 2014 (Report). Exeter, England. May 16, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ↑ NOAA predicts near-normal or below-normal 2014 Atlantic hurricane season. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Report) (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ↑ "FSU COAPS Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast". Florida State University Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies. Florida State University. May 22, 2014. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Strike Probability for 2014" (PDF). Colorado State University. July 31, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ↑ "August Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2014". Tropical Storm Risk. August 5, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ↑ "NOAA’s updated Atlantic hurricane season outlook calls for an increased chance". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 7, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ↑ Philip J. Klotzbach and William M. Gray (December 10, 2008). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2009" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived from the original on June 12, 2009. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ↑ "NOAA's Atlantic Hurricane Season Classifications". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. National Hurricane Center. May 22, 2008. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Climatology". National Hurricane Center. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ↑ Mike Watkins (July 3, 2014). "Arthur makes landfall as a Category 2 Hurricane". HurricaneTrack. HurricaneTrack. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ↑ Wes Hohenstein (July 4, 2014). "Arthur hits NC with 100 mph winds, earliest strike in NC history". WNCN News. WNCN News. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (June 25, 2014). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Eric S. Blake (June 27, 2014). Tropical Weather Outlook. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Robbie J. Berg (June 28, 2014). Tropical Weather Outlook. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric). Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (July 1, 2014). Tropical Depression One Discussion Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (July 1, 2014). Tropical Storm Arthur Discussion Number 3. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ Michael J. Brennan (July 3, 2014). Hurricane Arthur Discussion Number 10. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (July 3, 2014). Hurricane Arthur Intermediate Advisory Number 12B. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Jack L. Beven; Eric S. Blake (July 3, 2014). "Hurricane Arthur Tropical Cyclone Update". National Hurricane Center. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown; Richard J. Pasch (July 5, 2014). Post-Tropical Cyclone Arthur Discussion Number 12. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Weather History for Freeport, Bahamas: June 30, 2014". Weather Underground. June 30, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Weather History for Freeport, Bahamas: July 1, 2014". Weather Underground. July 1, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Arthur Strengthens off Florida". Newsmax. The Associated Press. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ↑ Andrew Kennedy and Anne Blythe (July 3, 2014). "Category 2 Hurricane Arthur pummeling coastal sounds, Outer Banks". The News & Observer. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Post Tropical Cyclone Report for Hurricane Arthur". Newport/Morehead, North Carolina National Weather Service. July 8, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ↑ Alexander Smith (July 4, 2014). "Hurricane Arthur Makes East Coast Landfall, 44,000 Without Power". NBC News. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ↑ David Zucchino (July 4, 2014). "Hurricane Arthur heads north, out to sea after hitting North Carolina". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Hurricane Arthur Causes Flooding On Cape Cod, South Coast". CBS Boston. July 4, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Intermediate Tropical Cyclone Information Statement for Post-Tropical Cyclone Arthur. Canadian Hurricane Center (Report) (Environment Canada). July 6, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Storm Arthur damage 'as bad as Hurricane Juan'". CBC News. July 7, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (September 24, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Two (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ↑ Eric S. Blake (December 18, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Bertha (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ Michael Brennan (August 23, 2014). Tropical Depression Four Public Advisory Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (August 25, 2014). Hurricane Cristobal Update Statement. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ Hurricane Cristobal Tropical Cyclone Report

- ↑ "Hurricane Cristobal Kills 5 in the Caribbean, Moves North". Weather Underground. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (September 1, 2014). Tropical Depression Five Public Advisory Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart; Robbie Berg (September 2, 2014). Tropical Storm Dolly Intermediate Advisory Number 2A. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ↑ Daniel Brown (September 2, 2014). Tropical Storm Dolly Public Advisory Number 6. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ Richard Pasch (September 3, 2014). Remnants of Dolly Public Advisory Number 8. National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ↑ Miriam Vallejano (September 3, 2014). "Deja Dolly 1 muerto, 3 comunidades aisladas y daños en Tampico Alto" (in Spanish). Conexión Total. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ↑ Armando Castillo (September 18, 2014). "Estiman en 80 millones daños en red carretera" (in Spanish). La Verdad de Tamaulipas. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Estiman en 7 mdp daños en El Mante por "Dolly"" (in Spanish). Milenio. September 12, 2014. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (December 10, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Edouard (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ↑ Hailey Winslow (September 17, 2014). "Beachgoers warned of high risk of rip currents". Jacksonville, Florida: News4Jax. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ↑ Dinah Voyles Pulver (September 15, 2014). "Hurricane may bring good waves to Volusia, Flagler". The Daytona Beach News-Journal. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Strong Rip Currents Kill Two Men in Ocean City". NBC4 Washington. September 18, 2014. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ↑ "BWS: Hurricane Edouard Is "Potential Threat"". Bernews. September 15, 2014. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Research drones launched into Hurricane Edouard". Associated Press. Miami, Florida: WNCN. September 16, 2014. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ↑ Rob Gutro (September 17, 2014). "Edouard (was TD6 - Atlantic Ocean)". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 Todd B. Kimberlain (December 17, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Fay (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ Raymond Hainey, Jonathan Bell and Simon Jones (October 13, 2014). "Island counts cost of Fay's fury". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ↑ Olivia Demarinis (October 15, 2014). "Hurricane Takes Aim at Bermuda". Latin Post. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Major Hurricane Gonzalo Targets Bermuda After Killing 1 in St. Maarten, Injuring 12 Others in Antigua". The Weather Channel. October 15, 2014. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Daniel P. Brown (January 20, 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Gonzalo (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (October 13, 2014). "Tropical Storm Gonzalo Discussion Number 5". National Hurricane Center. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Antigua residents clean up after Gonzalo brings heavy flooding, high winds". Caribbean Media Corporation. St. Johns, Antigua: Caribbean 360. October 14, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Hurricane Gonzalo strengthens, threatens Bermuda". The Associated Press. CBC News. October 14, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Gonzalo exacts a heavy toll on boats, boat owners". The Daily Herald. Marigot, St. Martin: The Daily Herald. October 14, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart (October 18, 2014). "Hurricane Gonzalo Tropical Cyclone Update". National Hurricane Center. Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ The Royal Gazette staff (October 18, 2014). "Belco restoration: 13,022 without power at 9pm". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ The Royal Gazette staff (October 18, 2014). "Roads blocked and serious damage Island-wide". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ Jeffrey Masters (October 19, 2014). "Gonzalo Brushes Newfoundland; Ana Drenching Hawaii". Weather Underground. Weather Underground. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ CBC News (October 19, 2014). "Hurricane Gonzalo douses Newfoundland, moves offshore". CBC News. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ Cathy Owen (October 21, 2014). "Wales weather: Hurricane Gonzalo brings winds of 70mph as it hits country". Wales Online. Wales Online. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Sturmtief Gonzalo ist am Dienstagabend über Baden-Württemberg hinweggefegt und hat auch in". Ad-Hoc News (in German). Ad-Hoc News. October 22, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ Jason Samenow (October 22, 2014). "Gonzalo’s final blow: Strong winds, heavy rain, and snow in Europe". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ Rodrigo Cokting (October 26, 2014). "Remnants of Gonzalo flood Athens". The Weather Network. The Weather Network. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 John P. Cangialosi (December 16, 2014). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Hanna (PDF). National Hurricane Center (Report) (Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center (April 17, 2015). "Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Arthur power outage may have contributed to Woodstock death". CBC News. July 9, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Hurricane Bertha claims UK victim: Yachtsman killed after being hit in the head by boat's boom as he sailed in gale-force winds". August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Hurricane Cristobal Kills 7: Two Swimmers Die in Rip Currents Off U.S. East Coast". August 28, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

External links

- National Hurricane Center Website

- National Hurricane Center's Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook

- Tropical Cyclone Formation Probability Guidance Product

| |||||||||||||