2001 Pacific hurricane season

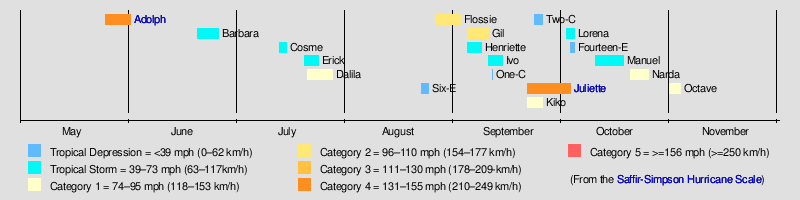

The 2001 Pacific hurricane season was an event in tropical cyclone meteorology. The most notable storm that year was Hurricane Juliette, which caused devastating floods in Baja California, leading to 12 fatalities and $400 million (2001 USD; $ USD) worth of damage. No other tropical cyclones in the 2001 Pacific hurricane season were notable.

The season officially began on May 15, 2001 in the eastern Pacific, and on June 1, 2001 in the central Pacific, and lasted until November 30, 2001. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in this part of the Pacific Ocean. The first storm developed on May 25, while the last storm dissipated on November 3.

Season summary

The 2001 Pacific hurricane season officially started May 15, 2001 in the eastern Pacific, and June 1, 2001 in the central Pacific, and lasted until November 30, 2001. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. In practice, however, the season lasted from May 25, the formation date of its first system, to November 3, the dissipation date of the last.

There were fifteen tropical storms in the eastern Pacific Ocean in the 2001 season. Of those, seven became hurricanes, of which two became major hurricanes by reaching Category 3 or higher on the Saffir Simpson Scale. Four tropical depressions formed and dissipated before reaching the intensity of a named storm. In the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's area of responsibility, only one tropical depression developed. In the eastern Pacific proper, the season saw average activity in terms of the number of systems, but with the intensity of the storms, the season was considered below average, with only seven hurricanes and two major hurricanes. This season had only one named storm in the month of June, and only one during August. Also of note this season is an unusual gap in storm formation during the first three weeks of August. That time usually sees several nameable storms, but for some reason there were none.

Storms

Hurricane Adolph

Hurricane Adolph originated from a tropical wave that left Africa on May 7, and was poorly organized. It was not until May 18 that the storm showed some signs of development in the Atlantic Ocean. On, May 22 the wave crossed over, and on May 25 it intensified into Tropical Depression One-E, about south-southwest of Acapulco, Mexico. The system, after drifting a while, intensified into Tropical Storm Adolph the next day. Later, on May 27 Adolph was upgraded to a hurricane. Intensifying into a hurricane, Adolph rapidly intensified, and reached to Category 4 strength on May 28. Two days after, Adolph went under an eyewall replacement cycle, and weakened to a 115 mph (185 km/h) hurricane, which is minimal category 3 intensity. This trend of weakening continued, and deteriorated into a tropical storm. Passing over cooler waters, and stable air, Adolph dissipated on June 1.[1]

Tropical Storm Barbara

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | June 20 – June 26 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave that moved off the coast of Africa on June 1. The wave eventually entered the Pacific Ocean on June 10, though no further organization occurred until June 18.[2] The system slowly organized further over the next two days, and became Tropical Depression Two-E early on June 20.[3] Although the depression remained poorly organized, it was upgraded to Tropical Storm Barbara.[4] At 1200 UTC on June 21, the storm attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 997 mbar (29.4 inHg). Shortly thereafter, Barbara began encountering unfavorable conditions, such higher wind shear and cooler sea surface temperatures.[5]

It weakened to a tropical depression at 1800 UTC on June 26, while crossing 140°W into the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's area of responsibility. The depression passed north of the Hawaiian Islands on June 25, then weakened to an easterly wave to the northwest of Kauai on June 26. The remnants of Barbara continued west-northwest until being absorbed by a frontal zone near the International Dateline on June 30.[2] Barbara was the first and only tropical cyclone in the Central Pacific during the month of June.[6]

Tropical Storm Cosme

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 13 – July 15 | ||

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) | ||

A tropical wave that crossed Central America and emerged into the eastern Pacific basin on July 6.The wave moved slowly westward from July 6 – July 10. On July 10, the convective pattern began to show signs of organization about south of Acapulco, Mexico, and the system received its first Dvorak satellite classification. Over the next two days, the system moved generally west-northwestward as multiple low-level circulations developed within a broad area of low pressure. During this period, development of the disturbance was hindered by southerly shear from an upper-level trough to the west of the disturbance that caused the system to become elongated north-south. On July 12, the upper trough cut off southwest of the disturbance and the organization improved. By early on July 13, a single low-level circulation center had become established and it is estimated that a tropical depression formed at 330 mi (530 km) southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico.[7]

Tropical Depression Three-E moved west-northwestward, and quickly became Tropical Storm Cosme on July 13, about south of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. The forward motion then slowed over the next 12 hours. Cosme's development was hindered by easterly shear; its peak intensity of 45 mph (72 km/h) was reached late on July 13. By early on July 14, convection was limited and well removed from the center. Cosme weakened back to a tropical depression, when it was about 400 mi (640 km) southwest of Cabo San Lucas. Cosme produced no more significant convection after about on July 15, at which point the tropical cyclone became a non-convective low center. The low then moved slowly westward until it dissipated on July 18 about 820 mi (1,320 km) west-southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico.[7]

Tropical Storm Erick

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 20 – July 24 | ||

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) 1001 mbar (hPa) | ||

Erick apparently formed from a poorly defined tropical wave that traveled westward across the tropical Atlantic and reached the eastern North Pacific on July 16. The thunderstorm activity associated with the wave increased on July 18 when the disturbance was centered about 808 mi (1,300 km) south of the southern tip of Baja California. Thereafter, deep convection gradually developed around a large cyclonic gyre which accompanied the wave.[8]

It was not until July 20 that a well-defined center of circulation formed and satellite intensity estimates supported tropical depression status. Moving on a general west-northwest track, the system became a tropical storm and reached maximum winds of and 1001 mbar (hPa; 29.56 inHg) minimum pressure July 22. It then moved over relatively cooler waters and weakened as the deep convection quickly vanished. By July 24, it was just a non-convective and dissipating swirl of low clouds, although some showers re-developed intermittently.[8]

Hurricane Dalila

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | July 21 – July 28 | ||

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 982 mbar (hPa) | ||

Dalila's origin is a tropical wave that moved westward from Africa and over the eastern tropical Atlantic Ocean on July 10. It crossed northern South America and Central America on the July 15 through July 17 accompanied by vigorous thunderstorm activity, and then entered the Pacific basin on July 18 as an organized area of disturbed weather. Early on July 21, the system acquired a low-level circulation and became Tropical Depression Five-E, about 250 mi (400 km) south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec. Moving west-northwestward, it became Tropical Storm Dalila with winds 12 hours later.[9]

Dalila's track was toward the west-northwest at forward speeds between five and . The direction of motion was rather steady, varying between 285 and 300 degrees heading. This is attributed to a persistent subtropical ridge of high pressure located north of the cyclone. The center reached its point of closest approach to the coast of Mexico between Acapulco and Manzanillo on the July 22 and July 23, when it came within about of the coast.[9]

With warm sea surface temperatures and minimal vertical shear, the winds increased from 40 to 70 mph (64 to 113 km/h) on July 22 and July 23. The wind speed briefly reached an estimated 75 mph (121 km/h) on July 24, although Dalila quickly weakened back to a strong tropical storm. The storm passed directly over Socorro Island on July 25. By July 27, most of the associated deep convection dissipated as the storm moved over colder water. Reduced to a swirl of low clouds, Dalila dissipated as a tropical cyclone on July 28, while located about 650 mi (1,050 km) west of the southern tip of Baja California.[9]

Tropical Depression Six-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | August 22 – August 24 | ||

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) | ||

The origins of the sixth tropical depression of the season are somewhat unknown, but it is possibly as a result of a westward moving tropical wave, which crossed the Atlantic and Caribbean.[10] By 2100 UTC on August 22, the National Hurricane Center began issuing advisories on Tropical Depression Six-E.[11] However, post-analysis indicate that developed of Tropical Depression Six-E occurred nine hours earlier. Three hours before the National Hurricane Center initiated advisories, it was indicated that Tropical Depression Six-E had attained its peak intensity, remaining just below tropical storm intensity.[10] Further intensification was deemed unlikely by the National Hurricane Center, as Tropical Depression Six-E would soon enter a region of sea surface temperatures less than 77 °F (25 °C).[11] In addition to lowering sea surface temperatures, Tropical Depression Six-E began to be affected by southerly wind shear, which displaced the mid-level circulation and deep convection from the low-level circulation.[12][13] The National Hurricane Center later noted the disorganized state of the tropical depression as being only "... a swirl of low clouds with a few showers to the north and northeast of the center".[14] Tropical Depression Six-E was becoming elongated, and the final advisory was issued early on August 24.[15] Because Tropical Depression Six-E remained far from land, there were no associated fatalities or damage.[10]

Hurricane Flossie

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic Ocean on August 11, and spawned Atlantic Tropical Storm Chantal three days later. After tracking westward toward the Yucatán Peninsula, the southern portion of the tropical wave split and entered the Pacific Ocean on August 21 after crossing Central America. The system initially failed to organize while paralleling the coast of Mexico, although there was a closed circulation by August 23. On August 25, outer rainbands produced tropical storm force winds near Manzanillo, Mexico; but the circulation was considered too broad and disorganized to be classified as a tropical depression. The low-level circulation began to become well-defined as it moved away from Mexico on August 26, while convection had consolidated near the center.[16] Later that day, it was classified as Tropical Depression Seven-E. Conditions appeared very favorable for development,[17] and after banding features increased, the system was upgraded to Tropical Storm Flossie later on August 26.[18] While steering currents weakened,[16] Flossie began to develop a cloud-filled eye on August 27, and was upgraded to a hurricane based on that and wind estimates of 75 mph (120 km/h).[19]

After becoming a hurricane, Flossie interacted with an extratropical low while slowly intensifying. By early on August 29, further intensification was not expected,[20] although Flossie suddenly deepened to a category 2 hurricane.[21] After winds reached 105 mph (165 km/h), Flossie entered a region with sea surface temperatures less than 79 °F (26 °C).[22] Flossie weakened quickly, and was only a minimal hurricane 24 hours after peak intensity, which is when the National Hurricane Center noted an ill-define eye.[23] Early on August 30, Flossie weakened to a tropical storm.[24] On September 1, Flossie was downgraded to a tropical depression,[25] and after becoming devoid of deep convection,[26] the system degenerated into a remnant low on September 2.[27] The remnants of Flossie moved inland over Baja California, eventually entering the southwestern region of the United States and dissipating.[16] The remnants caused flash-flooding in San Diego and Riverside Counties, California, dropping 2 in (50.8 mm) of rain in one hour. A strong downdraft knocked a tree onto a house. In addition, four people were struck by lightning, two of them fatally. The total cost of damage caused by Flossie's remnants was $35,000 (2001 USD, $46.6 thousand 2015 USD).[16]

Hurricane Gil

Gil originated from a tropical wave that emerged into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Africa on August 14 or August 15. By August 21, the tropical wave began to show signs of development as it neared the Lesser Antilles, with the northern portion becoming Tropical Storm Dean. Entering the Pacific on August 24,[28] Tropical Depression Eight-E did not developed until early on September 4. Situated roughly 850 mi (1,370 km) southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico,[29] the system quickly intensified, and became a tropical storm six hours later,[28] although operationally upgraded after nine hours.[30] By early on September 5, banding features became well-defined; the National Hurricane Center simultaneously noted the possibility for interaction between Tropical Storm Gil and Tropical Depression Nine-E (later Tropical Storm Henriette), which was 863 mi (1389 km) east-northeast.[31] Although outflow from Tropical Storm Henriette was predicted to slow or prevent intensification,[32] Gil managed to become a hurricane early on September 6.[33] Late on September 6, Hurricane Gil intensified into a category 2 hurricane, and attained its peak intensity, with winds reaching 100 mph (155 km/h).[28]

After becoming a category 2 hurricane, Gil curved northwestward, and began to become affected by northeasterly outflow associated with Tropical Storm Henriette. By September 7, Hurricane Gil became noticeably disorganized, and weakened back to a category 1 hurricane.[34] After weakening to a category 1 hurricane, Hurricane Gil accelerated due north, around the circulation of Henriette.[28] Further shearing from Henriette occurred, and early on September 8, the National Hurricane Center noted that the center of Gil was near the edge of the associated deep convection.[35] After over a region with sea surface temperatures near 73 °F (23 °C), Gil rapidly weakened, and was downgraded to a tropical storm six hours later.[36] Gil continued to weaken, and was downgraded to a tropical depression early on September 9.[37] Weakening to a tropical depression, Gil eventually absorbed the remnants of Henriette, but dissipated by midnight UTC, on September 10.[28]

A ship known as the Pacific Highway passed 236 mi (380 km) southeast of Gil on September 7, and reported waves heights at 22 ft (6.7 m) and winds gusting to 46 mph (76 km/h). However, Hurricane Gil did not affect land.[28]

Tropical Storm Henriette

A tropical wave, that crossed over Central America on August 28 – August 19, began showing some signs of development some hundreds south of Acapulco, Mexico. Early morning visible satellite images on September 4 revealed a partially exposed, but well defined low-level circulation. While deep convection was confined to the southwestern half of the circulation, the convection was close enough to the center for Dvorak satellite intensity estimates to increase to 30–35 mph (45–55 km/h), and the system became Tropical Depression Nine-E on September 4, about 300 mi (480 km) west-southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico, and also about 765 mi (1,231 km) east of Tropical Depression Eight-E (which was to become Hurricane Gil). Early on September 5, as the depression's heading turned to the west, the separation between the circulation center and the deep convection.[38]

Tropical Depression Nine-E became Tropical Storm Henriette on September 5, about 350 mi (560 km) south-southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. At this time, Tropical Storm Gil was located about to the west of Henriette. Henriette slowly became better organized on September 6. The convective pattern became more symmetric and the intensity increased to 60 mph (97 km/h). Meanwhile, Henriette turned to the northwest and accelerated to a forward speed of 17–20 mph (27–32 km/h) as it began to feel the influence of Hurricane Gil, then located to the southwest. Upper-level easterly flow, which was still evident over the cyclone early on September 6, lessened and a more favorable outflow pattern began to develop. Convective banding near the center became better defined, and Henriette reached its peak intensity of 65 mph (105 km/h) on September 7.[38]

Tropical Storm Henriette began weakening due to cold waters, and its proximity to Gil. A Fujiwhara interaction began with Henriette and Gil on September 8. Henriette dissipated as a tropical cyclone when it lost its own closed low-level circulation, as evidenced by low-cloud trajectories, shortly after on the September 8. At the time of dissipation, Henriette was located about 210 mi (340 km) west of Tropical Storm Gil.[38]

Tropical Storm Ivo

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 10 – September 14 | ||

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) | ||

Ivo formed from a large tropical wave that moved off the African coast on August 26. The wave was accompanied by a large cyclonic rotation at the low to middle levels and numerous thunderstorms when it entered the eastern Atlantic. On August 28, the wave spawned a northward-moving vortex in the eastern Atlantic, but the wave's southern portion continued westward with very limited convective activity. Once the wave reached the western Caribbean Sea on September 5, the shower activity increased and the whole system continued slowly westward over Central America. The cloud pattern gradually became better organized and by September 9, satellite images showed a low to middle level circulation centered near Acapulco, Mexico. The next day, a portion of the system moved over water and it became a tropical depression about 118 mi (190 km) south-southwest of Acapulco at September 10.[39]

The center of the depression moved slowly west and west-northwestward with its circulation hugging the southwest coast of Mexico. There was moderate easterly shear over the depression as indicated by the location of the convection to the west of the center. Satellite images and a report from a ship indicated that the depression reached tropical storm status by 0600 UTC September 11. Thereafter, there was only slight strengthening and Ivo reached its maximum intensity of and an estimated minimum pressure of 997 mbar (hPa; 29.44 inHg) on September 12. The tropical storm moved toward the northwest and then west over increasingly cooler waters, and gradually weakened. It became a low pressure system devoid of convection by the end of September 14.[39]

Tropical Depression One-C

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 11 – September 11 | ||

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) | ||

Tropical Depression One-C formed on September 11 more than 400 mi (644 km) southeast of the Island of Hawaii. The system moved west northwestward to 15°N 153°W by September 11, and then southwestward shortly thereafter. The system was poorly organized, and the convection of Tropical Depression One-C dissipated later on September 11. Having only lasted 12 hours as a depression; Tropical Depression One-C never reached tropical storm strength.[40]

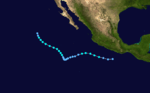

Hurricane Juliette

An area of disturbed weather associated with the remnants of Atlantic Tropical Depression Nine organized directly into Tropical Storm Juliette on September 21. Sustained intensification began the next day. Juliette eventually peaked as a Category 4 hurricane with a central pressure of 923 mbar (hPa; 27.26 inHg), which made it the fifth-most intense Pacific hurricane at the time. Juliette turned north and weakened and made landfall as a minimal hurricane. Juliette's remnants hung on for a few more days until they dissipated on October 3.[41]

Juliette dumped heavy rains on the Baja California Peninsula and in Sonora, where it caused two deaths. Its effects were especially hard on Cabo San Lucas, Baja California Sur, which was cut off from the outside world for a few days. The remnants of Juliette moved into the state of California, where they caused thunderstorms, rain, and some downed power lines.[41] The total estimated cost of damage was $400 million (2001 USD; $ 2015 USD).[42]

Hurricane Kiko

A tropical wave that led to the formation Atlantic Hurricane Felix over the eastern Atlantic on September 7 also seems to have produced Kiko. This wave moved westward at low latitudes, crossing northern South America on September 13 – September 14 and Central America on September 15 and September 16. By September 17, cloudiness and showers increased near the Gulf of Tehuantepec. The area of disturbed weather moved westward for the next few days, without much increase in organization. On September 21, the system's cloud pattern became more consolidated, and curved bands of showers were evident. It is estimated that Tropical Depression Twelve-E had formed that day, at which time it was centered about 634 mi (1,020 km) southwest of the southern tip of Baja California.[43]

After forming, the system, which was located in an environment of easterly vertical shear, strengthened slowly. By September 22 the organization of the cloud pattern improved to the extent that tropical storm strength was estimated to have been reached. Kiko turned from a northwestward to a west-northwestward heading that day. Although some easterly shear continued to affect the system, very deep convection persisted near the center, and based on Dvorak intensity estimates, Kiko strengthened into a hurricane around September 23. A little later on September 23, deep convection decreased in coverage and intensity and Kiko weakened back to a tropical storm.[43]

The system continued to lose intensity on September 24, at least in part due to the entrainment of more stable air at low levels. Kiko weakened to a tropical depression on September 25, by which time southwesterly shear also became prevalent. Later on September 25, the cyclone degenerated into a westward-moving swirl of low clouds with little or no deep convection. Kiko's remnant low persisted and continued moving generally westward for several more days with intermittent, minor occurrences of deep convection within the circulation. It was finally absorbed into a frontal system to the northeast of the Hawaiian Islands on October 1.[43]

Tropical Depression Two-C

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | September 23 – September 25 | ||

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1008 mbar (hPa) | ||

Tropical Depression Two-C formed near 10°N 147.4°W on September 22, southwest of Tropical Storm Kiko (in the East Pacific). Throughout September 23, Tropical Depression Two-C remained a poorly organized system that slowly moved west-northwestward. A slight increase in convection became apparent on September 24, and was followed by a period of consistent thunderstorm activity near the circulation center. Tropical Depression Two-C continued in the west-northwest direction, but weakened by September 25.[40]

Tropical Storm Lorena

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 2 – October 4 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) | ||

The tropical wave that eventually developed into Lorena moved off the west coast of Africa on September 13. The poorly defined wave tracked rapidly westward across the Atlantic for more than a week. There was little or no thunderstorm activity associated with the wave until it moved across Central America on September 27. Significant deep convection finally developed on September 29 and satellite classifications began on September 30 when the system was located about 300 mi (480 km) south of Acapulco, Mexico. The wave possessed a well-defined closed low-level circulation at that time.[44]

Convection steadily increased and banding features developed during the day on October 1. Satellite intensity estimates indicate the system became Tropical Depression Thirteen-E at October 2. Low-level circulation had tightened up considerably and satellite intensity estimates indicated the depression had strengthened into Tropical Storm Lorena about 350 mi (560 km) south-southwest of Acapulco. Lorena tracked steadily west-northwestward at eight to 14 mph (23 km/h) the remainder of the day and gradually turned toward the northwest early on October 3. The peak intensity of 60 mph (97 km/h) occurred later that day as Lorena took a more northerly track when it was located about southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico.[44]

By October 4, the forward speed of Tropical Storm Lorena had decreased to around seven to nine mph (11 to 14 km/h) and strong upper-level southwesterly shear began to adversely affect the cyclone. Lorena weakened to a tropical depression and dissipated into a non-convective low later that day about 120 mi (190 km) southwest of Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. The remnant low-level cloud circulation remained offshore and persisted for another day or so before completely dissipating just west of Cabo Corrientes, Mexico.[44]

Tropical Depression Fourteen-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 3 – October 4 | ||

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1008 mbar (hPa) | ||

Tropical Depression Fourteen-E developed from a small swirl of low clouds that was first observed along the Intertropical Convergence Zone well to the south-southwest of Baja California on September 30. Little development occurred until October 3, which is when the system began to generate more persistent deep convection.[45] While the system was located about 800 mi (1,300 km) southwest of the southern tip of Baja California, the National Hurricane Center began to classify it as Tropical Depression Fourteen-E. Although it appeared that wind shear was at initially predicted to remain at a favorable level,[46] an upper-level low to the southwest of the depression generated wind shear greater than expected, and convection significantly weakened only hours later. Despite significant effects from wind shear, the depression was still forecast to intensify into a tropical storm.[47] Later that day, the low-level center of the depression became more difficult to locate on satellite images, and the location of the poorly defined center was estimated.[48] Convection significantly decreased again early on October 4, and the depression was declared dissipated 900 mi (1,400 km) southwest of the southern tip of Baja California.[49] The remnant low cloud swirl continued westward for another 24–36 hours before dissipating completely.[45]

Tropical Storm Manuel

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 10 – October 18 | ||

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) | ||

Tropical Storm Manuel formed from the remnants of Hurricane Iris from the Atlantic Basin. The core circulation of Iris had dissipated over the mountains of eastern Mexico, while new convection was developing a short distance away over the waters of the Pacific. This area became better organized over the next 18 hours and became Tropical Depression Fifteen-E at October 10, about 175 mi (282 km) south-southeast of Acapulco, Mexico. The depression moved at 15–16 mph (24–26 km/h), first westward and then west-northwestward. An upper-level anticyclone centered over southern Mexico was producing some easterly shear in the environment of the depression, but when this shear lessened the system became Tropical Storm Manuel on October 11, about 200 mi (320 km) south-southwest of Zihuatanejo, Mexico. An estimated initial peak intensity of 50 mph (80 km/h) was reached that day when the first clear banding features developed. However, the banding was short-lived, deep convection diminished, and satellite microwave imagery early on October 12 suggested that the circulation was becoming elongated. Wind shear returned, this time from the northwest, and Manuel turned to a west-southwesterly track and slowed. By October 12, Manuel had weakened to a tropical depression.[50]

Manuel remained a disorganized depression for the next two and a half days. It continued moving to the west-southwest, but slowed to a drift as a mid-level ridge to the north of the cyclone gradually weakened. An upper-level trough dug southward to the west of Manuel early on October 15, and Manuel began to move to the north-northwest. Convection redeveloped near the center and Manuel regained tropical storm strength on October 15 about 596 mi (959 km) south-southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. Wind shear decreased and Manuel strengthened, reaching its peak intensity of 60 mph (97 km/h) winds, and a pressure of 997 mbar (hPa; 29.44 inHg) on October 16 about 540 mi (870 km) southwest of Cabo San Lucas. By this point, water temperatures under the cyclone were decreasing and shear, this time from the southwest, was increasing. Manuel began to weaken while moving to the west-northwest and northwest. It became a depression at October 17 about 660 mi (1,060 km) west-southwest of Cabo San Lucas, and dissipated to a non-convective low shortly after October 18. The remnant low moved slowly westward for a couple of days over cool waters before its circulation dissipated completely.[50]

Hurricane Narda

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 20 – October 25 | ||

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 980 mbar (hPa) | ||

Narda developed from a westward moving tropical wave that crossed Dakar, Senegal around the October 3. The wave became convectively active after it crossed Central America when it produced a large burst of convection in the Bay of Campeche on the October 15. The southern portion of the wave continued westward over the Pacific waters south of Mexico and under favorable upper-level winds, it began to acquire banding features and several centers of circulation. The system finally consolidated and developed one center at October 20. It became a tropical depression about 1,150 mi (1,850 km) southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. Moving on a west-northwest track, it intensified and reached tropical storm status later that day. The cloud pattern continued to become better organized and visible satellite imagery showed an intermittent eye feature, and it is estimated that Narda became a hurricane at October 21. Narda peak's intensity of 980 mbar (hPa; 28.94 inHg) occurred on October 22. Thereafter, a gradual weakening began and strong shear took a toll on Narda. The tropical cyclone became a tight swirl of low clouds with intermittent convection on October 24, as it moved westward steered by the low-level flow and crossing 140°W over the Central Pacific area of responsibility. It then continued westward as a tropical depression until dissipation. [51]

Hurricane Octave

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Duration | October 31 – November 3 | ||

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 980 mbar (hPa) | ||

Octave originated in the intertropical convergence zone and its development was likely initiated by a weak tropical wave that had moved westward across Central America on October 22. By October 27, convection had increased over a large area between 95 – 115° W longitude and between eight and 15° north latitude.[52] A low-level circulation gradually developed within this area and became a tropical depression on October 31 while centered about 1,180 mi (1,900 km) southwest of the southern tip of Baja California. Becoming a tropical depression, it was initially affected by easterly upper-level winds, and outflow was restricted on the eastern quadrant.[53] The cyclone started out to the south of a mid-layer ridge, but a weakness soon developed in this ridge from a trough approaching from the west. The depression intensified, and with evidence of banding features and increased organization, the storm was upgraded to Tropical Storm Octave.[54] Although cloud tops began to warm on October 31, Octave continued to improve on organization,[55] and the National Hurricane Center noted that the storm began to resemble a hurricane early on November 1.[56]

Shortly thereafter, no significant further intensification was predicted, as the cloud pattern was becoming elongated, vertical wind shear would soon increase, and Octave would soon entering a region of decreasing sea surface temperatures.[57] Octave began to re-organize, and an eye feature began developing on November 1.[58] A ragged eye eventually developed, and T-numbers of 4.0 were reached on the Dvorak Scale, which resulted in the National Hurricane Center upgrading Octave to a hurricane.[59] Wind quickly increased to 85 mph (140 km/h), and because of unfavorable conditions predicted to affect Octave, the National Hurricane Center believed that it had attained peak intensity.[60] Octave had in fact, attained its peak intensity, with maximum sustained winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 980 mbar (hPa; 28.94 inHg).[52] Wind shear began to increase, while sea surface temperatures were decreasing, and infrared satellite imagery revealed that the low-level circulation was becoming displaced from the associated deep convection just after peak intensity, it had remained a hurricane,[61] until the National Hurricane Center downgraded Octave to a tropical storm on November 2.[62] By early on November 3, only minimal deep convection was associated with Octave,[63] and the National Hurricane Center downgraded the system to a tropical depression later on that day.[64] Deep convection associated with Octave remained minimal, and the system had degenerated into a remnant low located about 1,715 mi (2,760 km) west-southwest of the southern tip of Baja California.[65] Hurricane Octave remained far from land, and no damage or fatalities were reported.[52]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms that formed in the northeast Pacific in 2001. The names not retired from this list were used again in the 2007 Pacific hurricane season. This is the same list used for the 1995 season except for Ivo, which replaced Ismael. A storm was named Ivo for the first time in 2001. Names that were not assigned are marked in gray.

|

|

|

For storms that form in the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's area of responsibility, encompassing the area between 140 degrees west and the International Date Line, all names are used in a series of four rotating lists. The next four names that were slated for use in 2001 are shown below, however none of them were of them were used.

|

|

|

|

Retirement

After the season had begun the names Adolph and Israel were retired for political considerations, after a row brewed over the use of their names.[66][67][68]

See also

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- List of Pacific hurricane seasons

- 2001 Atlantic hurricane season

- 2001 Pacific typhoon season

- 2001 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2000–01, 2001–02

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2000–01, 2001–02

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2000–01, 2001–02

References

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (June 18, 2001). "Hurricane Adolph Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Beven, Jack (August 7, 2001). "Tropical Storm Barbara Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Kelly, Robert / Loos, Treena / Kodama, Kevin (February 2002). "2001 Tropical Cyclones Central North Pacific". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Franklin, James (July 18, 2001). "Tropical Storm Cosme Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Avila, Lixion (July 31, 2001). "Tropical Storm Erick Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Lawrence, Miles (August 13, 2001). "Hurricane Dalila Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2

- ↑ 11.0 11.1

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (August 23, 2001). "Tropical Depression Six-E Discussion #4". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ Cobb, Hugh & Franklin, James (August 23, 2001). "Tropical Depression Six-E Discussion #6". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Stewart, Stacy (October 27, 2001). "Hurricane Flossie Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard (August 26, 2001). "Tropical Depression Seven-E Discussion #1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Beven, Jack (August 29, 2001). "Hurricane Flossie Discussion #13". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Pasch, Richard; Rhome, Jamie (August 29, 2001). "Hurricane Flossie Discussion #19". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ↑ Molleda, Robert; Avila, Lixion (August 30, 2001). "Tropical Storm Flossie Discussion #20". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ↑ Lawrence, Miles (September 1, 2001). "Tropical Depression Flossie Discussion #26". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ↑ Lawrence, Miles (September 1, 2001). "Tropical Depression Flossie Discussion #27". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ↑ Jarvinen, Brian (September 2, 2001). "Tropical Depression Flossie Discussion #28". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 Beven, Jack (October 25, 2001). "Hurricane Gil Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ↑

- ↑ Franklin, James (September 4, 2001). "Tropical Storm Gil Special Discussion #3". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ Beven, Jack & Molleda, Robert (September 5, 2001). "Tropical Storm Gil Discussion #5". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ Franklin, James (September 5, 2001). "Tropical Storm Gil Discussion #7". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard & Aguirre-Echevarria, Jorge (September 6, 2001). "Hurricane Gil Discussion #8". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ Franklin, James (September 7, 2001). "Hurricane Gil Discussion #15". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ Jarvinen, Brian & Molleda, Robert (September 8, 2001). "Hurricane Gil Discussion #17". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑

- ↑ Beven, Jack (September 9, 2001). "Hurricane Gil Discussion #21". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Brown, Daniel / Franklin, James (September 24, 2001). "Tropical Storm Henriette Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Avila, Lixion (October 23, 2001). "Tropical Storm Ivo Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Kelly, Robert / Loos, Treena / Kodama, Kevin (2001). "2001 Tropical Cyclones Central North Pacific". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Lawrence, Miles and Mainelli, Michelle (November 30, 2001). "Hurricane Juliette Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ↑ "Search Details Disaster List". Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Pasch, Richard (December 18, 2001). "Hurricane Kiko Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Stewart, Stacy (November 30, 2001). "Tropical Storm Lorena Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Beven, Jack (October 24, 2001). "Tropical Depression Fourteen-E Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ Beven, Jack (October 3, 2001). "Tropical Depression Fourteen-E Discussion #1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard; Molleda, Robert (October 3, 2001). "Tropical Depression Fourteen-E Discussion #2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard; Molleda, Robert (October 3, 2001). "Tropical Depression Fourteen-E Discussion #3". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ↑ Franklin, James; Knabb, Rick; Aguirre-Echevarria, Jorge (October 4, 2001). "Tropical Depression Fourteen-E Discussion #4". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Franklin, James (October 31, 2001). "Tropical Storm Manuel Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 18 October 2010. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (November 13, 2001). "Hurricane Narda Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Lawrence, Miles (December 6, 2001). "Hurricane Octave Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (October 31, 2001). "Tropical Depression Seventeen-E Discussion #1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard (October 31, 2001). "Tropical Storm Octave Discussion #2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ↑ Beven, Jack (October 31, 2001). "Tropical Storm Octave Discussion #4". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (November 1, 2001). "Tropical Storm Octave Discussion #5". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard (November 1, 2001). "Tropical Storm Octave Discussion #6". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (November 1, 2001). "Tropical Storm Octave Discussion #7". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard (November 1, 2001). "Hurricane Octave Discussion #8". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (November 2, 2001). "Hurricane Octave Discussion #9". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Pasch, Richard (November 2, 2001). "Hurricane Octave Discussion #11". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Lawrence, Miles (November 2, 2001). "Tropical Storm Octave Discussion #12". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Cobb, Hugh / Avila, Lixion (November 3, 2001). "Tropical Storm Octave Discussion #13". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Jarviven, Brian (November 3, 2001). "Tropical Depression Octave Discussion #15". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Jarviven, Brian (November 3, 2001). "Tropical Depression Octave Discussion #16". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Wohlhelernter, Elli (2001-05-21). "Storm brewing over hurricane named Israel". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2012-07-21. (Accessed through the HighBeam Research archives.)

- ↑ "Storm blows over as 'Hurricane Israel' is retired". The Jerusalem Post. 2001-06-06. Retrieved 2012-07-21. (Accessed through the HighBeam Research News archives.)

- ↑ Padgett Gary; Beven, John (Jack) L; Lewis Free, James; Delgado, Sandy; The Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory's Hurricane Research Division (2012-06-01). "Subject: B3) What storm names have been retired?". Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Questions. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Oceanic and Atmospherc Research office. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

External links

- NHC 2001 Pacific hurricane season archive

- HPC 2001 Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Pages

- Central Pacific Hurricane Center

- Gary Padgett's monthly storm summaries and best tracks

| |||||||||||||

| ||||||