1946 Florida hurricane

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

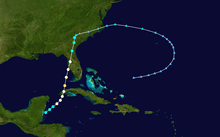

Map of the storm on October 8 | |

| Formed | October 5, 1946 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated |

October 14, 1946 (extratropical after October 8) |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 100 mph (155 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 977 mbar (hPa); 28.85 inHg |

| Fatalities | 5 total |

| Damage | $5.2 million (1946 USD) |

| Areas affected | Cuba, Florida, Southeastern United States |

| Part of the 1946 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The 1946 Florida hurricane was the last hurricane to make landfall in the Tampa Bay Area of the U.S. state of Florida. Forming on October 5 from the complex interactions of several weather systems over the southern Caribbean Sea, the storm rapidly strengthened before striking western Cuba. After entering the Gulf of Mexico, it peaked with winds corresponding to Category 2 status on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale; however, it quickly weakened before approaching Florida. It made landfall south of St. Petersburg and continued to weaken as it proceeded inland. Its remnants persisted for several days longer.

In advance of the storm, preparations were taken along threatened areas of coastal Florida, including the evacuation of thousands of residents. Damage was extensive in Cuba, and five people were killed there. The cyclone's effects in the United States were minor to moderate, and the most significant impact was to citrus crops. No deaths occurred in the country, although high tides caused some flooding of low-lying terrain. The cyclone's structure was extensively observed and investigated.

Meteorological history

At the end of September 1946, the Intertropical Convergence Zone in the Eastern Pacific moved north of its typical position. An associated weather disturbance moved over Central America and interacted with a surface low-pressure area over Guatemala. Meanwhile, a broad high-pressure area moved over the United States behind an intense storm that moved eastward into the Atlantic Ocean. Connected to the cyclone was a shear line stretching from Bermuda to the Caribbean Sea, which spawned an upper-level low over open waters. It moved westward on October 4, and by the next day it was located over the Southeastern United States. The feature over Guatemala began moving toward the northeast as the upper-level low approached and began deepening.[1] Modern-day analysis estimates that the system became a tropical storm early on October 5, shortly after emerging into the Caribbean.[2]

The storm moved slowly northeastward, steadily intensifying. On October 6, it attained maximum sustained winds corresponding to Category 1 status on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale. It began accelerating as it curved northward, and on October 7, the hurricane crossed extreme western Cuba with sustained winds of 90 miles per hour (145 km/h) and a central pressure of 977 millibars (28.85 inHg).[2] As it emerged into the Gulf of Mexico, the cyclone peaked with winds of 100 mph (161 km/h), equivalent to low-end Category 2 status, on October 7. It only held its peak intensity for six hours, after which a minimum barometric pressure of 979 mb (28.91 inHg) was recorded, the lowest known air pressure in relation to the storm.[2] The rapid deepening of the storm was described as "difficult to account for," and the conditions that caused it—as well as those that led to its dissipation—"may be regarded as extraordinary."[1]

Immediately after peaking in severity, the storm weakened quickly: after skirting the Dry Tortugas in the lower Florida Keys, it moved ashore early on October 8 near Cortez, near Bradenton—just south of St. Petersburg—with winds of 85 mph (137 km/h).[2] Cortez measured a pressure of 980 mb (28.94 inHg) as the calm eye of the hurricane passed overhead.[1] The storm deteriorated into a tropical storm as it proceeded inland, and further into an extratropical cyclone with gale-force winds on October 9. Its remnants emerged from the coast of North Carolina into the Atlantic and curved southeastward, then bending westward again before dissipating on October 14.[2]

Preparations and impact

Hurricane warnings were issued for coastal areas of Florida,[3] including the Florida Keys and the Panhandle. Storm advisories were also posted along the state's Atlantic coast,[4] and portions of the Eastern Seaboard. They were discontinued on October 8, although small craft warnings remained in place along the Northeastern Coast.[3] Pan American Airways canceled flights between Miami and Havana, Cuba, and also to Guatemala and Mérida, Yucatán. Small navy vessels were secured, while larger ships rode out the storm at sea.[4] In the Key West neighborhood of Poinciana Plaza, 2,000 residents evacuated their homes. Emergency shelters in the area were opened, and local business slowed considerably with the exception of a few grocery stores selling emergency supplies. Schools closed as windows were boarded up on houses and businesses.[5] Throughout its course, the hurricane was heavily observed and investigated, resulting in an abundance of information that provided a more comprehensive understanding of a tropical cyclone's vertical structure. It was profiled in detail in a Monthly Weather Review article by R. H. Simpson, titled "A Note on the Movement and Structure of the Florida Hurricane of October 1946".[1]

The hurricane's passage across western Cuba was accompanied by wind gusts of 112 mph (180 km/h).[6] Sugar cane crops there were destroyed, cutting supplies to the United States by several tons.[7] Towns lost communication with outside areas due to the hurricane,[3] and reports indicate that five people in the country were killed.[6]

Prior to the storm's arrival in Florida, its outer fringes caused gusty winds and torrential rainfall, causing some minor freshwater flooding of streets.[5] The cyclone also spawned a tornado which struck the city of Tampa and inflicted minor damage.[3] Sustained five-minute winds reached 80 mph (129 km/h) at the Dry Tortugas. Tides along the shore ran up to 9.5 ft (2.9 m) above-normal, and rainfall amounted to over 6 in (150 mm) at Ocala.[6] Winds in the United States were not extreme; the storm's impact was considered relatively minor.[8] Properties incurred around $200,000 in damage, primarily from high tides. Flooding up to 3 ft (0.91 m) deep occurred in Everglades, Punta Gorda, and Fort Myers, as well as other low-lying locations.[6] Wharves, piers and warehouses sustained some damage, while sporadic power outages were reported.[8] Citrus farms suffered fairly severe damage, accounting for as much as 2% of the total crop and $5 million in losses. No fatalities were reported in the state. Further north, in southeastern Georgia, gusty winds blew in relation to the storm.[6]

See also

- List of Florida hurricanes (1900–1949)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 R. H. Simpson (April 1947). "A Note on the Movement and Structure of the Florida Hurricane of October 1946" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review (American Meteorological Society) 75 (4): 53–58. Bibcode:1947MWRv...75...53S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1947)075<0053:ANOTMA>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 14, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (March 2, 2015). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Florida Hurricane Loses Its Force". The Pittsburgh Press. October 8, 1946. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Noon Storm Advisory". The Miami News. October 7, 1946.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Thousands Flee Their Homes as Hurricane Nears Florida". Spokane Daily Chronicle. October 7, 1946. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 H. C. Sumner (December 1946). "North Atlantic Hurricanes and Tropical Disturbances of 1946" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review (American Meteorological Society) 74 (12): 216–217. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1946)074<0215:nahatd>2.0.co;2. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ↑ "First Winds Strike Coast As Florida Stands By For Hurricane Lashings". Herald-Journal. October 8, 1946. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Barnes 1998, pp. 169–70

Bibliography

- Jay, Barnes (1998), Florida's Hurricane History, Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Chapel Hill Press, ISBN 0-8078-2443-7

External links

| |||||||||||||