1945 Homestead hurricane

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane on September 16 | |

| Formed | September 12, 1945 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 20, 1945 |

| (Extratropical after September 18) | |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 130 mph (215 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 949 mbar (hPa); 28.02 inHg |

| Fatalities | 26 total |

| Damage | $60 million (1945 USD) |

| Areas affected | Leeward Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Bahamas, Florida, Georgia, The Carolinas |

| Part of the 1945 Atlantic hurricane season | |

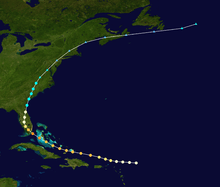

The 1945 Homestead hurricane was the most intense tropical cyclone to strike the U.S. state of Florida since 1935. The ninth tropical storm, third hurricane, and third major hurricane of the season, it developed east-northeast of the Leeward Islands on September 12. Moving briskly west-northwestward, the storm became a major hurricane on September 13. The system moved over the Turks and Caicos Islands the following day and then Andros on September 15. Later that day, the storm peaked as a Category 4 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h). Late on September 15, the hurricane made landfall on Key Largo and then in southern Miami-Dade County.

Thereafter, the hurricane began to weaken while moving across Florida, falling to Category 1 intensity only several hours after landfall late on September 15. Eventually, it curved north-northeastward and approached the east coast of Florida again. Late on September 16, the storm emerged into the Atlantic near St. Augustine and weakened to a tropical storm early on the following day. The cyclone made another landfall near the Georgia-South Carolina state line later on September 17. The system continued to weaken and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone near the border of North Carolina and Virginia early on September 18.

The storm caused significant damage and 22 deaths in the Turks and Caicos Islands and the Bahamas. In Florida, the hardest hit area was Miami-Dade County. Most of the city of Homestead was destroyed, while at the Richmond Naval Air Station, a fire ignited during the storm burned down three hangars worth $3 million (1945 USD) each. Throughout the state, the strong winds destroyed 1,632 residences and damaged 5,372 homes others. Four people died, including the fire chief of the Richmond station. In the Carolinas, the storm produced heavy rainfall, causing flash flooding, particularly along the Cape Fear River in North Carolina. Overall, the hurricane resulted in 26 fatalities and about $60 million in damage.

Meteorological history

The hurricane was first observed on September 12 about 235 mi (380 km) east-northeast of Barbuda in the Lesser Antilles. Around that time, the winds were estimated at 75 mph (120 km/h), and later that day, the Hurricane Hunters recorded peripheral winds of 54 mph (87 km/h). Moving quickly to the west-northwest, the hurricane quickly intensified while passing north of Puerto Rico, reaching the equivalent of a modern-day major hurricane with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). The strength was based on another Hurricane Hunters mission reporting flight-level winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). After passing north of Hispaniola, the hurricane turned moved toward the Bahamas, approaching or passing over Grand Turk Island at 0530 UTC on September 14. A station on the island observed a barometric pressure of 977 mbar (28.9 inHg) during the passage, and nearby Clarence Town reported winds of 104 mph (168 km/h). While moving through the Bahamas, the hurricane turned more to the northwest. It was a smaller than average storm, and continued intensifying while moving toward southeastern Florida.[1]

At 1930 UTC on September 15, the hurricane made landfall on Key Largo, and about a half hour later struck the Florida mainland.[1] The center passed very close to Homestead Air Reserve Base about an hour after landfall, where a central barometric pressure of 951 mbar (28.1 inHg) was recorded.[1][2] The observation suggested a landfall pressure of 949 mbar (28.0 inHg), and based on its small size and peak winds of 130 mph (215 km/h); equivalent to a Category 4 on the current Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. This estimate was backed up by gust of 138 mph (222 km/h) at Carysfort Reef Light. The hurricane weakened over Florida while curving to the north and north-northeast, although the proximity to water and the passage over the Everglades limited substantial weakening. Hurricane force winds spread across much of Florida until the storm emerged into the western Atlantic near St. Augustine late on September 16. At around 0000 UTC the next day, the hurricane weakened to tropical storm status. About 11 hours later, it made another landfall near the border between Georgia and South Carolina with winds of 70 mph (120 km/h).[1]

After continuing through the southeast United States, the storm became extratropical near the border of North Carolina and Virginia midday on September 18. Although it initially maintained tropical storm-force winds, the former hurricane weakened below gale-force on September 19 while it was near Philadelphia. The storm continued rapidly to the northeast, moving through New England and along the coast of Maine before turning more to the east. Late on September 19, the storm moved across Nova Scotia, passing southeast of Newfoundland the next day. It was last observed late on September 20 dissipating to the east of Newfoundland.[1]

Preparations

Although hurricane warnings were initially issued for the Leeward Islands, the cyclone passed north of the Lesser Antilles.[1] In advance of the storm, aircraft were evacuated from the Naval Air Station in Miami, Florida, where hundreds of planes left vulnerable locations.[3] [4] Residents were advised to heed advisories in Florida, the Bahamas, and northern Cuba.[5] On September 15, hurricane force winds were expected to affect areas from Fort Lauderdale, Florida through the Florida Keys, and hurricane warnings were accordingly released for this region. Storm warnings also extended north to Melbourne and Tampa.[4] Military personnel sought shelter at Hialeah Race Track, while residents boarded homes and evacuated from coastal areas to public structures.[4] Boats were utilized to transport people from barrier islands, and small watercraft were secured along the Miami River.[4] However, Grady Norton, the head of the United States Weather Bureau, stated before the storm that Miami would "miss the worst of it".[6] The American Red Cross reported that 25,000 people sought shelter within their services during the storm.[6] Local officials from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina to Brunswick, Georgia ordered evacuations for coastal locations.[7]

Impact

In the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands, 22 people were killed.[2] The hurricane demolished three-quarters of the structures on Grand Turk Island, while the remaining intact buildings were damaged.[8] The cyclone also produced heavy damage on Long Island, though damages were not reported in Nassau.[9] Peak gusts were estimated near 40 mph (65 km/h) in Nassau.[8] After the storm, The Daily Gleaner initiated a fund to offer aid for residents in the Turks and Caicos Islands.[8]

In south Florida, peak gusts were estimated near 150 mph (240 km/h) at the Army Air Base in Homestead. The strong winds destroyed 1,632 residences across the state, while 5,372 homes received damages.[2] In Miami, gusts reached 107 mph (170 km/h), and damages were minimal, mostly snapped power lines, compared to communities in southern Dade County.[2][6] Nearly 200 people were injured at the Richmond Naval Air Station, when a fire ignited during the storm, affecting three hangars worth $3 million each and destroying 25 blimps, 366 planes, and 150 automobiles.[10] Damages to the Miami area was estimated at $40 million.[6] An additional fire also destroyed a furniture factory and a tile manufacturing plant in the northwestern portion of downtown Miami.[10] One death was reported in the area, the fire chief of Richmond's fire department, and 26 required hospitalization. Another death was recorded after a schooner ran aground in present-day Bal Harbour, Florida, killing its chief engineer.[6]

Homestead was mostly flooded underwater, with the first floor of city hall and the fire department completely flooded and nearly all its residences destroyed. The historical Horde Hardware building collapsed while a local church was flatted by the winds. In the Florida Keys, hundreds of residences were damaged. The Florida East Coast Railway station at Goulds collapsed. Crop losses was estimated to be $4 million and most of its avocado harvest was destroyed.[6] Four people died across the state.[2]

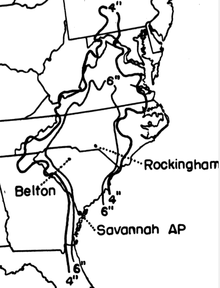

Minor reports of damage was reported in Central and Northern Florida, with St. Augustine reporting a 70 mph (110 km/h) wind gust.[7] In Charleston, South Carolina, strong winds caused high waves, but the storm arrived at low tide and produced modest damage.[11] Rainfall peaked at 8.0 inches (200 mm) at Belton, South Carolina.[12] In Aiken, South Carolina, heavy precipitation caused damage to unpaved streets.[13] Inland, the system produced heavy rainfall over North Carolina,[14] peaking at 14.8 inches (380 mm) in Rockingham, North Carolina in the period covering September 13 through September 18.[12] This rain led to saturated grounds, allowing new water to spill into streams. Many crop fields and dwellings were flooded near the Cape Fear River as levels rose to record heights. The towns of Moncure, Fayetteville, and Elizabethtown exceeded flood stage levels. Broken dams in Richmond County produced significant flash floods. Few deaths were reported, but economic losses were extensive.[14] In Hopewell, New Jersey, the remnants of the system produced winds of 50 mph (80 km/h), though major damage was not reported.[15]

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the storm, more than 1,000 Red Cross workers were activated in response to the cyclone.[16] A force of 400 German prisoner of wars and 200 Bahamian laborers participated in the cleanup process.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Christopher Landsea et al. (June 2013). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1945) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 H. C. Sumner (1946-04-14). "North Atlantic Hurricanes and Tropical Disturbances of 1945" (PDF). United States Weather Bureau 74 (1). Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- ↑ "Tropical Wind Nears Florida". The Lima News. Associated Press. 1945.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Advance Hurricane Winds Hit Florida". Dunkirk Evening Observer. United Press International. 1945.

- ↑ "Florida On Alert As Gale Sweeps Towards The Keys". The Lewiston Daily News. Associated Press. September 15, 1945. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 "Worst Storm Candidate". The Miami News. August 4, 1957. p. 135-136. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Tropical Storm Loses Its Fury As It Heads North". The St. Petersburg Evening Independent (Associated Press). September 16, 1945. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Not a House in Turks Islands Escapes Damage". Sunday Gleaner. 1945.

- ↑ "Bahamas Island Sends Report of Great Damage by Hurricane". The Independent-Record. Associated Press. 1945.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Violent Hurricane Sweeps Florida". The La Crosse Tribune. Associated Press. 1945.

- ↑ "Atlantic Hurricane Losing Fury After Striking S. Carolina". United Press International. 1945.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 United States Corp of Engineers (1945). Storm Total Rainfall In The United States. War Department. p. SA 5-27.

- ↑ "Worst Fury of Storm Missed Aiken But Some Damage Done". Aiken Daily Standard and Review. 1945.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 James E. Hudgins (2000). Tropical Cyclones Affecting North Carolina since 1566 – An Historical Perspective. National Weather Service Blacksburg, Virginia (Report). Archived from the original on 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ The Hopewell Herald (1945). "Borough Deluged for Two Days".

- ↑ "Hurricane Lashes Southern Florida". Ogden Standard-Examiner. 1945.

| |||||||||||||