1910 Cuba hurricane

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

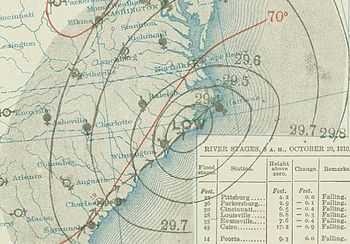

Surface map of the storm on October 10 | |

| Formed | October 9, 1910 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 23, 1910 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 150 mph (240 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 924 mbar (hPa); 27.29 inHg |

| Fatalities | ≥113 |

| Damage | At least $1.25 million (1910 USD) |

| Areas affected | Cuba, Florida |

| Part of the 1910 Atlantic hurricane season | |

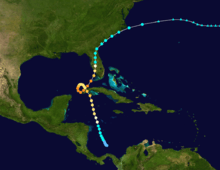

The 1910 Cuba hurricane, popularly known as the Cyclone of the Five Days, was an unusual and destructive tropical cyclone that struck Cuba and the United States in October 1910. It formed in the southern Caribbean on October 9 and strengthened as it moved northwestward, becoming a hurricane on October 12. After crossing the western tip of Cuba, it peaked in intensity on October 16, corresponding to Category 4 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. That same day, the hurricane moved in a counterclockwise loop and hit Cuba again. It then tracked toward Florida, landing near Cape Romano. After moving through the state, it hugged the coast of the Southeastern United States on its way out to sea.

Due to its unusual loop, initial reports suggested it was two separate storms that developed and hit land in rapid succession. Its track was subject to much debate at the time; eventually, it was identified as a single storm. Analysis of the event gave a greater understanding of weather systems that took similar paths.

The hurricane is considered one of the worst natural disasters in Cuban history. Damage was extensive, and thousands were left homeless. It also had a widespread impact in Florida, including the destruction of houses and flooding. Although total monetary damage from the storm is unknown, estimates of losses in Havana, Cuba exceed $1 million and in the Florida Keys, $250,000. At least 100 deaths occurred in Cuba alone.

Meteorological history

On October 9, the fifth tropical depression of the 1910 season formed from a tropical disturbance in the extreme southern Caribbean, to the north of Panama. It tracked steadily northwestward, and attained tropical storm intensity on October 11. It continued to strengthen, and became a hurricane the next day.[1] On October 13, the storm was observed to the southwest of Cuba.[2] Early on October 14, the hurricane briefly reached an intensity corresponding to Category 3 status on the modern-day Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale before tracking ashore along the western tip of Cuba. However, it weakened somewhat after crossing the island. Upon emerging into the Gulf of Mexico, the hurricane slowed considerably.[1]

Steered by currents from an area of high pressure to the north, the storm began to drift northwestward and rapidly deepen over warm waters of the Gulf. It executed a tight counterclockwise loop, and continued to mature;[3] on October 16 it reached peaked winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) with a minimum barometric pressure of 924 mbar (hPa; 27.29 inHg).[1] The hurricane turned northeastward, again approaching western Cuba, and began to accelerate towards the Florida Peninsula on October 17.[1] Its center passed west of Key West and made landfall near Cape Romano.[3] The storm moved due north for a time as it moved inland, and deteriorated into a tropical storm. From northeastern Florida, the cyclone curved northeastward and hugged the coast of the Southeast United States before heading out to sea.[3] The storm is estimated to have dissipated on October 23.[1]

The storm is unusual in that due to its loop near Cuba, initial reports suggested that it was actually two separate cyclones.[3] The Monthly Weather Review describes the event as multiple disturbances and reports that the first hurricane dissipated in the central Gulf of Mexico after crossing Cuba, while the second formed subsequently and hit Florida.[2] At the time, the storm's track was subject to much debate. It was later identified as a single storm, although observations on the hurricane led to advances in the understanding of tropical cyclones with similar paths.[3] On October 19, The Washington Post wrote, "Whether two storms have been raging in Cuban waters within the past week, or whether the same storm has revisited Cuba, traversing southern Florida in its backwards course, remains to be determined. If the later supposition be correct, the recurve of the storm, after its entrance into the Gulf of Mexico, must have been unusually sudden and sharp."[4]

Impact

On October 15, all vessels within a 500 mi (800 km) radius of Key West were warned of the approaching storm, and many ships anchored in harbors.[5] Throughout the region, storm warnings and advisories were issued.[2]

Cuba

The storm wrought severe destruction in Cuba, considered to be among the worst effects from a tropical cyclone on record. High winds and torrential rainfall flooded streets, destroyed crops,[2] and damaged plantations. In particular, the storm caused substantial damage to the tobacco in the region of Vuelta Abajo.[6] Many towns were severely damaged or destroyed.[7] The city of Casilda was devastated,[8] while the town of Batabanó was inundated by flood waters. The hurricane cut off communications to inland areas.[9] The majority of the fatalities and property damages were suspected to be in the Pinar del Río province.[10]

The New York Times wrote that Cuba had "probably suffered the greatest material disaster in all its history".[11] It was reported that thousands of peasants were left homeless due to the cyclone. Losses in Havana were also extensive; along the shore, scores of ships carrying valuable cargo had sunk. The storm also seriously damaged goods stored on local wharves and barges.[12] "Tremendous" waves crashed ashore, flooding coastal areas.[13] Numerous ships and small watercraft were wrecked by the cyclone.[14][15] The raging seas submerged about 1 sq mi (2.6 km2) of Havana's oceanfront land. The Malecón sea wall breached, allowing flood waters to engulf the roadway there and residences in the area.[11]

It is estimated that at least 100 people lost their lives, mostly due to mudslides, including five persons in Havana.[16][17] However, reports range as high as 700.[18] Initial estimates of the financial damage caused by the storm were in the millions of dollars, including losses of $1 million in Havana, largely from the destruction of Customs House sheds there, which were filled with many valuable goods.[11] Some of these buildings were swept 0.5 mi (0.80 km) away, and the winds tore the roof off the main warehouse.[10] In the aftermath—while the hurricane was still widely considered to be two separate storms—rumors arose "of the approach of a third storm",[11] although in actuality no additional storms were known to have occurred in the 1910 season.[1]

Holliswood

A four-masted schooner, the Holliswood, became trapped in the storm in the Gulf of Mexico. The vessel departed from New Orleans on October 1, carrying cypress wood. The crew fought the storm for days and eventually the masts were cut to avoid capsizing.[19] Waterlogged, the ship was blown miles off course.[20] As described by the owner of the schooner, Paul Mangold:[19]

On Wednesday, the 12th, we began to get the first of the hurricane. We were running under very little canvas. Early Saturday morning we got the full force of the storm. We managed to get the sails fast and ran with the hurricane under bare poles. The wind circled about us sometimes at a hundred-mile rate. The seas came from all directions, though it was from the starboard that the real trouble seemed to come.

The steamboat Harold spotted the ship and rescued all of its crew except Captain E. E. Walls, who opted to stay behind with the order "Report me to my owners".[19] At the time, the Holliswood was badly damaged, with her house destroyed and her rudder torn away. The crew apparently advised the captain that the ship would not stay afloat for another five hours, although he dismissed their concerns. After the crew was rescued, Captain Walls struggled against the storm for days without food or fresh water. On October 20, the Parkwood rescued Walls unconscious, but initially feared to be dead.[20] Once aboard, he regained consciousness and, reportedly amidst an episode of delirium, asked to be returned to the Holliswood. Ultimately, the captain of the Parkwood agreed to tow the battered ship to shore.[20]

Southern Florida

At Key West, pressures began to fall at midnight on October 12 as the storm approached from the southwest. By late on October 13, heavy rain had begun to fall, and winds began to increase, reaching 50 mph (80 km/h) on October 14.[2][17] Gusts reached 110 mph (180 km/h) and storm tide ran 15 ft (4.6 m); swells in the area attained "unusually high" levels. Many docks were destroyed, and on October 17, the basement of the Weather Bureau office was submerged by rising waters.[21] Before the rain gauge was washed out to sea, 3.89 in (99 mm) of precipitation was recorded. Damage throughout the Florida Keys was moderate, estimated at worth around $250,000 (1910 USD). Property damage was generally limited to structures along the shore.[2]

As the storm progressed westward, Tampa and nearby locations started to experience its effects. Strong winds from the northeast blew water out of the Tampa Bay to the lowest level ever recorded. The barometer fell to 961 mbar (hPa; 28.4 inHg), and extremely high waves battered the shore from Flamingo to Cape Romano. The surf continued well inland, forcing survivors to cling atop trees.[21] North of Tampa, the hurricane's effects were moderate or light, while in the southwestern part of the state, damage increased in severity. A portion of the local citrus crop was destroyed.[2] Property damage was widespread from Tampa to Jacksonville and points south. High winds tore the roofs off homes and shook some structures off their foundations.[22]

Seven men lost their lives in the wreckage of several Cuban schooners at Punta Gorda. Nearby, one man and a baby drowned as a result of the storm surge, and another died while attempting to cross a flooded river.[2] A French steamship, the Louisiane, went ashore with 600 passengers; all people aboard the vessel were rescued by the Forward, a Revenue cutter.[21]

Northeastern Florida and southern United States

Damage on the Atlantic coast was less severe, although at Jupiter, the Weather Bureau office reported: "the rainfall at this point did more damage than the wind. It had rained every day from the 3rd to the 13th, with a total fall of 5.96 inches (151 mm), and the creeks and flat woods were full of water when the first storm began. From the 14th to the 18th, inclusive, 14.27 inches (362 mm) more fell. The inlet being closed the rivers rose 8 feet (2.4 m) above normal high water, which in a flat country like this, puts practically all land under water from 1 foot (0.30 m) to 8 feet (2.4 m). Fortunately the sea remained low and comparatively smooth so that it was possible to open the inlet and let the water out."[21]

A large number of pine trees were blown down near the city of Jupiter. One man near Lemon City was killed by falling timber. Small watercraft, docks and boathouses sustained damage, but otherwise the storm's effects on the east coast were more moderate compared to other areas. Portions of the Florida East Coast Railroad bed were washed out, and repairs were anticipated to be costly. An American schooner blew ashore at Boca Raton, killing three and leaving the rest of the crew stranded for 12 hours until help arrived. Estimates of the cyclone's impact on citrus crops in the region vary widely.[2]

On its way to sea, the storm passed just west of Jacksonville. Although very little damage occurred in and around the city, persistent northeasterly winds caused flooding in low-lying coastal areas. Minor flooding extended northward into Georgia and South Carolina; initially, interruptions of communication between cities led to exaggerated reports of damage in those states. Early on October 18, light precipitation began to fall in Savannah as the winds picked up. By October 19, winds had reached 70 mph (110 km/h). However, it was said that the city's worst damage came as a result of the high tides rather than the intense winds. Certain rivers exceeded their banks, submerging surrounding farmland. Minor damage occurred in Charleston, South Carolina.[2]

See also

- List of Florida hurricanes (1900–1949)

- List of Category 4 Atlantic hurricanes

- Geography of Cuba

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Hurricane Specialists Unit (2010). "Easy to Read HURDAT 1851–2009". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Charles F. von Herrmann (October 1910). "District No. 2, South Atlantic and East Gulf States" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review (American Meteorological Society) 38 (10): 1488–1491. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1910)38<1456:WFAWFT>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Barnes, p. 93

- ↑ "The West Indian Hurricane". The Washington Post. October 19, 1910.

- ↑ "Hurricane Nears the Florida Coast". The New York Times. October 15, 1910. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ↑ "Great Storm in Cuba: Severe Damage Done to the Tobacco Crop". The Observer. October 16, 1910. p. 9.

- ↑ "West Indian Hurricane". The Scotsman. October 18, 1910.

- ↑ "Terrific Hurricane". The Evening Post. October 15, 1910. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ↑ "Hurricane in Cuba Costs Many Lives". The Spokane Daily Chronicle. October 17, 1910. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Cyclone in Cuba". The Scotsman. October 18, 1910.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "Cyclone Works Havoc in Cuba" (PDF). The New York Times. October 18, 1910. p. 1. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ "The Hurricane in Cuba". The Manchester Guardian. October 17, 1910. p. 7.

- ↑ "Hurricanes Have Overwhelmed Cuba". The Galveston Daily News. October 18, 1910.

- ↑ "West Indian Hurricane". The Scotsman. October 19, 1910.

- ↑ "The Hurricane Moving North". The Manchester Guardian. October 20, 1910.

- ↑ Longshore, p. 109

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Liners Defy Cyclone". The Washington Post. October 15, 1910. p. 1.

- ↑ "Cuba Hurricanes Historic Threats: Chronicle of hurricanes in Cuba". Cuba Hurricanes. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "Sticks to His Ship, a Derelict at Sea" (PDF). The New York Times. October 25, 1910. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "Skipper, Who Stood by Ship, Picked Up". The New York Times. October 27, 1910. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Barnes, p. 94

- ↑ "West Indian Storm and Cold Wave May Meet". The Galveston Daily News. October 19, 1910.

References

- Barnes, Jay (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. Chapel Hill Press. ISBN 0-8078-3068-2.

- Longshore, David (2008). Encyclopedia of Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Cyclones. Checkmark Books. ISBN 0-8160-7409-7.

External links

| |||||||||||||