Łódź

| Łódź | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Freedom Square, Manufaktura Centre, Lodz University of Technology, Piotrkowska Street, Poznański Palace, The "Łódź Manhattan", Medical University of Łódź, Academy of Fine Arts in Lodz, The White Factory | |||

| |||

| Motto: Ex navicula navis (From a boat, a ship) | |||

Łódź | |||

| Coordinates: 51°47′N 19°28′E / 51.783°N 19.467°ECoordinates: 51°47′N 19°28′E / 51.783°N 19.467°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Voivodeship | Łódź | ||

| County | city county | ||

| City Rights | 1423 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Hanna Zdanowska | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 293.25 km2 (113.22 sq mi) | ||

| Highest elevation | 278 m (912 ft) | ||

| Lowest elevation | 162 m (531 ft) | ||

| Population (2013) | |||

| • City | 715 360 | ||

| • Metro | 1,428,600 | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 90-001 to 94–413 | ||

| Area code(s) | +48 42 | ||

| Car plates | EL | ||

| Website | http://www.uml.lodz.pl/ | ||

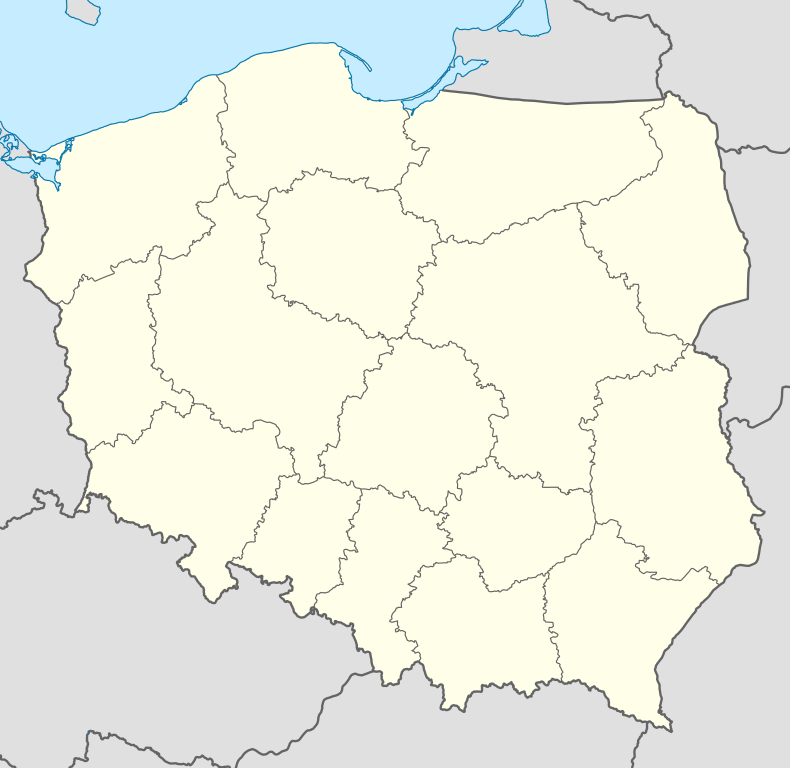

Łódź (Polish pronunciation: [wut͡ɕ]; Yiddish: לאדזש, Lodzh; English pronunciation: /luːdʒ/ or /lɒdz/[1]) is the third-largest city in Poland. Located in the central part of the country, it had a population of 742,387 in December 2009. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is approximately 135 kilometres (84 mi) south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of canting: depicting a boat, it alludes to the city's name which translates literally as "boat."

History

Łódź first appears in the written record in a 1332 document giving the village of Łodzia to the bishops of Włocławek. In 1423 King Władysław Jagiełło granted city rights to the village of Łódź. From then until the 18th century the town remained a small settlement on a trade route between Masovia and Silesia. In the 16th century the town had fewer than 800 inhabitants, mostly working on the nearby grain farms.

With the second partition of Poland in 1793, Łódź became part of the Kingdom of Prussia's province of South Prussia, and was known in German as Lodsch. In 1798 the Prussians nationalised the town, and it lost its status as a town of the bishops of Kuyavia. In 1806 Łódź joined the Napoleonic Duchy of Warsaw and in 1810 it had 190 inhabitants. In the 1815 Congress of Vienna treaty it became part of Congress Poland, a client state of the Russian Empire.

Century of partitions: 1815 Congress of Vienna

In the 1815 treaty, it was planned to renew the dilapidated town and with the 1816 decree by the Czar a number of German immigrants received territory deeds for them to clear the land and to build factories and housing. In 1820 Stanisław Staszic aided in changing the small town into a modern industrial centre. The immigrants came to the Promised Land (Ziemia obiecana, the city's nickname) from all over Europe. Mostly they arrived from Southern Germany, Silesia and Bohemia, but also from countries as far away as Portugal, England, France and Ireland. The first cotton mill opened in 1825, and 14 years later the first steam-powered factory in both Poland and Russia commenced operations. In 1839, 78% of the population was German,[2] and German schools and churches were established.

A constant influx of workers, businessmen and craftsmen from all over Europe transformed Łódź into the main textile production centre of the Russian Empire. Three groups dominated the city's population and contributed the most to the city's development: Poles, Germans and Jews, who started to arrive since 1848. Many of the Łódź craftspeople were weavers from Silesia.

In 1850, Russia abolished the customs barrier between Congress Poland and Russia proper; industry in Łódź could now develop freely with a huge Russian market not far away. Soon the city became the second-largest city of Congress Poland. In 1865 the first railroad line opened (to Koluszki, branch line of the Warsaw-Vienna Railway), and soon the city had rail links with Warsaw and Białystok.

One of the most important industrialists of Łódź was Karl Wilhelm Scheibler.[3] In 1852 he came to Łódź and with Julius Schwarz together started buying property and building several factories. Scheibler later bought out Schwarz's share and thus became sole owner of a large business. After he died in 1881 his widow and other members of the family decided to pay homage to his memory by erecting a chapel, intended as a mausoleum with family crypt, in the Lutheran part of the Łódź cemetery in ulica Ogrodowa (later known as The Old Cemetery).[4]

| Year | Inhabitants |

|---|---|

| 1793 | 190 |

| 1806 | 767 |

| 1830 | 4,300 |

| 1850 | 15,800 |

| 1880 | 77,600 |

| 1905 | 343,900 |

| 1925 | 538,600 |

| 1990 | 850,000 |

| 2003 | 781,900 |

| 2007 | 753,192 |

| 2009 | 742,387 |

In the 1823–1873, the city's population doubled every ten years. The years 1870–1890 marked the period of most intense industrial development in the city's history. Many of the industrialists were Jewish. Łódź soon became a major centre of the socialist movement. In 1892 a huge strike paralysed most of the factories. According to Russian census of 1897, out of the total population of 315,000, Jews constituted 99,000 (around 31% percent).[5] During the 1905 Revolution, in what became known as the June Days or Łódź insurrection, Tsarist police killed hundreds of workers.[6] By 1913, the Poles constituted almost half of the population (49.7%), the German minority had fallen to 14.8%, and the Jews made up 34%, out of some 506,000 inhabitants.[2]

Despite the air of impending crisis preceding World War I, the city grew constantly until 1914. By that year it had become one of the most densely populated industrial cities in the world—13,280 inhabitants per square kilometre (34,400/sq mi). A major battle was fought near the city in late 1914, and as a result the city came under German occupation after 6 December but with Polish independence restored in November 1918 the local population liberated the city and disarmed the German troops. In the aftermath of World War I, Łódź lost approximately 40% of its inhabitants, mostly owing to draft, diseases and because a huge part of the German population was forced to move to Germany.

Restored Poland after the First World War

In 1922, Łódź became the capital of the Łódź Voivodeship, but the period of rapid growth had ceased. The Great Depression of the 1930s and the Customs war with Germany closed western markets to Polish textiles while the Bolshevik Revolution (1917) and the Civil War in Russia (1918–1922) put an end to the most profitable trade with the East. The city became a scene of a series of huge workers' protests and riots in the interbellum.

On 13 September 1925 a new airport, Lublinek Airport, began operations on the outskirts of the city. In the interwar years Łódź continued to be a diverse and multicultural city, with the 1931 Polish census showing that the total population of roughly 604,000 included 375,000 (59%) Poles, 192,000 (32%) Jews and 54,000 (9%) Germans (determined from the main language used). By 1939, the Jewish minority had grown to well over 200,000.[7]

Occupation by Nazi Germany

During the invasion of Poland, the Polish forces of General Juliusz Rómmel's Łódź Army defended the city against initial German attacks. The Wehrmacht nevertheless captured the city on 8 September. Despite plans for the city to become a Polish enclave attached to the General Government, the Nazi hierarchy respected the wishes of many ethnic German residents and the Reichsgau Wartheland governor Arthur Greiser by annexing the city to the Reich in November 1939. Many Germans in the city, however, refused to sign the Volksliste and become Volksdeutsche; they were deported to the General Government. The city was given the new name of "Litzmannstadt" after Karl Litzmann, the German general who had captured it during World War I.

The Nazi authorities soon established the Łódź Ghetto in the city and populated it with more than 200,000 Jews from the Łódź area.[8] As Jews were deported from Litzmannstadt for extermination, others were brought in. Several concentration camps and death camps arose in the city's vicinity for the non-Jewish inhabitants of the regions, among them the infamous Radogoszcz prison and several minor camps for the Romani people and for Polish children. Due to the value of the goods that the ghetto population produced for the German military and various civilian contractors, it was the last major ghetto to be liquidated, in August 1944.

While occupied, thousands of new ethnic German Volksdeutsche came to Łódź from all across Europe, many of whom were repatriated from Russia during the time of Hitler's alliance with the Soviet Union before Operation "Barbarossa". In January 1945, most of the German population fled the city for fear of the Red Army. The city also suffered tremendous losses due to the German policy of requisition of all factories and machines and transporting them to Germany. Thus, despite relatively small losses due to fighting and aerial bombardment, Łódź was deprived of most of its infrastructure.

Prior to World War II, Łódź's Jewish community numbered around 233,000 and accounted for one-third of the city's total population. The community was wiped out in the Holocaust. By the end of the war, the city and its environs had lost approximately 420,000 of its pre-war inhabitants, including approximately 300,000 Polish Jews and 120,000 other Poles.[9]

The Soviet Red Army entered the city on 18 January 1945. According to Marshal Katukov, whose forces participated in the operation, the Germans retreated so suddenly that they had no time to evacuate or destroy factories, as they had in other cities.[10] Łódź subsequently became part of the People's Republic of Poland.

After World War II in the People's Republic

At the end of World War II, Łódź had fewer than 300,000 inhabitants. However the number began to grow as refugees from Warsaw and territories annexed by the Soviet Union immigrated. Until 1948 the city served as a de facto capital of Poland, since events during and after the Warsaw Uprising had thoroughly destroyed Warsaw, and most of the government and country administration resided in Łódź. Some planned moving the capital there permanently; however, this idea did not gain popular support and in 1948 the reconstruction of Warsaw began. Under the Polish Communist regime many of the industrialist families lost their wealth when the authorities nationalised private companies. Once again the city became a major centre of industry. In mid-1981 Łódź became famous for its massive, 50,000 hunger demonstration of local mothers and their children (see: Summer 1981 hunger demonstrations in Poland). After the period of economic transition during the 1990s, most enterprises were again privatised.

Economy

Before 1990, Łódź's economy focused on the textile industry, which in the nineteenth century had developed in the city owing to the favourable chemical composition of its water. Because of the growth in this industry, the city has sometimes been called the "Polish Manchester". As a result, Łódź grew from a population of 13,000 in 1840 to over 500,000 in 1913. By the time right before World War I Łódź had become one of the most densely populated industrial cities in the world, with 13,280 inhabitants per km2. The textile industry declined dramatically in 1990 and 1991, and no major textile company survives in Łódź today. However, countless small companies still provide a significant output of textiles, mostly for export to Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union.

The city benefits from its central location in Poland. A number of firms have located their logistics centres in the vicinity. Two motorways, A1 spanning from the north to the south of Poland, and A2 going from the east to the west intersect northeast of the city. As of 2012, A2 is complete to Warsaw and the northern section of A1 is largely completed. With these connections, the advantages due to the city's central location should increase even further. Work has also begun on upgrading the railway connection with Warsaw, which reduces the 2-hour travel time to make the 137 km (85 mi) journey to 1.5 hours in 2009. In the next few years much of the track will be modified to handle trains moving at 160 km/h (99 mph), cutting the travel time by an additional 15 minutes.

Recent years has seen many foreign companies opening offices in Łódź. Indian IT company Infosys has one of its centres in Łódź. Despite the fact that Łódź is regarded to be the poorest among Polish cities with population over 500,000, the GDP per capita in Łódź was 123.9% of Poland's average (2008).

In January 2009 Dell announced that it will shift production from its plant in Limerick, Ireland to its plant in Łódź, largely because the labour costs in Poland are a fraction of those in Ireland.[11] The city's investor friendly policies have attracted 980 foreign investors by January 2009.[11] Foreign investment was one of the factors which decreased the unemployment rate in Łódź to 6.5 percent in December 2008, from 20 percent four years earlier.[11]

Climate

| Climate data for Łódź | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.8 (55) |

17.5 (63.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

32.7 (90.9) |

35.0 (95) |

37.3 (99.1) |

37.6 (99.7) |

30.2 (86.4) |

25.4 (77.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.8 (58.6) |

37.6 (99.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

1.8 (35.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

5.8 (42.4) |

1.5 (34.7) |

12.3 (54.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.9 (66) |

18.3 (64.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.9 (48) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.7 (25.3) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.9 (57) |

13.2 (55.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−2.2 (28) |

4.8 (40.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.3 (−22.5) |

−27.4 (−17.3) |

−17.7 (0.1) |

−8 (18) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.0 (41) |

3.3 (37.9) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−16.8 (1.8) |

−20.8 (−5.4) |

−30.3 (−22.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 40.7 (1.602) |

36.3 (1.429) |

39.7 (1.563) |

33.5 (1.319) |

63.5 (2.5) |

65.2 (2.567) |

90.0 (3.543) |

56.5 (2.224) |

42.1 (1.657) |

37.6 (1.48) |

40.8 (1.606) |

35.9 (1.413) |

582 (22.91) |

| Avg. precipitation days | 17 | 15 | 14 | 11 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 166 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 42 | 54 | 113 | 171 | 237 | 224 | 229 | 227 | 156 | 105 | 49 | 36 | 1,644 |

| Source: | |||||||||||||

Tourism

The Piotrkowska Street which remains the high-street and main tourist attraction in the city, runs north to south for a little over five kilometres (3.1 miles). This makes it one of the longest commercial streets in the world. A few of the building façades, which date back to the 19th century, have been renovated. It is the site of most restaurants, bars and cafes in Łódź's city centre.

Łódź has one of the best museums of modern art in Poland, Muzeum Sztuki, on Więckowskiego (ms1) and Ogrodowa (ms2) Street which displays a 20th and 21st century art collection. The heart of the collection, setting its historical and aesthetic roots, is the International Collection of Modern Art of the avant-garde “a.r.” group. Due to its insufficient exhibition space (many very impressive paintings and sculptures have had to be put in storage in the basement) there are plans to build a larger space on Ogrodowa Street in the near future. Although there are no hills or any large body of water within Łódź, one can still get close to the nature at the city's many parks. The Lunapark, an amusement park featuring two dozen attractions, including an 18-metre tall roller coaster, is located near the city's zoo and botanical gardens. The largest 19th-century textile-factory complex, built by Izrael Poznanski, has been converted to a shopping centre called "Manufaktura".

In 1956, a monument in memory of the victims of the Łódź Ghetto, by Muszko was erected at the cemetery. The Jewish Cemetery at Bracka Street, one of the largest of its kind in Europe, was established in 1892. After the German occupation of Poland in 1939, this cemetery became a part of Łódź's eastern territory known as the enclosed Łódź ghetto (Ghetto Field). Between 1940 and 1944, approximately 43,000 burials took place within the grounds of this rounded-up cemetery. It features a smooth obelisk, a menorah, and a broken oak tree with leaves stemming from the tree (symbolizing death, especially death at a young age). As of 2014 the cemetery has an area of 39.6 hectare. It contains approximately 180,000 graves, approximately 65,000 labelled tombstones, ohels and mausoleums. Many of these monuments have significant architectural value; 100 of these have been declared historical monuments and have been in various stages of restoration. The mausoleum of Izrael and Eleanora Poznanski is perhaps the largest Jewish tombstone in the world and the only one decorated with mosaics.[12][13] On 20 November 2012 more than 20 gravestones, some were from the 19th century, were destroyed at the Jewish cemetery in an apparently anti-Semitic act.[14]

Education

Łódź is a thriving center of academic life. Currently Łódź hosts three major state-owned universities, six higher education establishments operating for more than a half of the century, and a number of smaller schools of higher education. The tertiary institutes with the most students in Łódź include:

- University of Łódź (Uniwersytet Łódzki)

- Lodz University of Technology (Politechnika Łódzka)

- Medical University of Łódź (Uniwersytet Medyczny w Łodzi)

- National Film School in Łódź (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Filmowa, Telewizyjna i Teatralna w Łodzi)

- Academy of Music in Łódź (Akademia Muzyczna im. Grażyna i Kiejstuta Bacewiczów w Łodzi)

- Strzemiński Academy of Art Łódź (Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Wł. Strzemińskiego w Łodzi)

There are also dozens of other schools and academies, but for the last four years the best students in Łódź (according to the prestigious contest "Studencki Nobel") have been studying at the University of Łódź – in 2009 the regional laureate was Piotr Pawlikowski, in 2010 – Joanna Dziuba, in 2011 and 2012 – Paweł Rogaliński.[15][16] In recent years, an estimated number of 15 private higher education establishments were created, which gives students better educational opportunities than before.

National Film School in Łódź

The Leon Schiller's National Higher School of Film, Television and Theatre in Łódź (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Filmowa, Telewizyjna i Teatralna im. Leona Schillera w Łodzi) is the most notable academy for future actors, directors, photographers, camera operators and TV staff in Poland. It was founded on 8 March 1948 and was initially planned to be moved to Warsaw as soon as the city was rebuilt following the Warsaw Uprising. However, in the end the school remained in Łódź and today is one of the best-known institutions of higher education in that town.

At the end of the Second World War Łódź remained the only large Polish town besides Kraków which war had not destroyed. The creation of the National Film School gave the town a role of greater importance from a cultural viewpoint, which before the war had belonged exclusively to Warsaw and Kraków. Early students of the School include the directors Andrzej Munk, Andrzej Wajda, Kazimierz Karabasz (one of the founders of the so-called Black Series of Polish Documentary) and Janusz Morgenstern, who at the end of the Fifties became famous as one of the founders of the Polish Film School of Cinematography.

Immediately after the war, Jerzy Bossak, Wanda Jakubowska, Stanisław Wohl, Antoni Bohdziewicz and Jerzy Toeplitz worked as the first teachers. The internationally renowned film director Roman Polański was among the many talented students who attended the School in the 1950s. Łódź's cinematic involvement and its Hollywood-style star walk on Piotrkowska Street have earned it the nickname "Holly-Łódź". The school is also associated with the Camerimage Film festival, which occurs annually in late November and early December. Founded in Toruń in 1993, the festival was specifically organised to focus on the art of cinematography and is well-attended every year by world-renowned cinematographers, many of whom also participate in seminars, workshops, retrospectives and Q&A sessions. Because of both subject matter and attendee composition, it is considered a key event for industry exhibitors, who often make European debuts of their products here.

Łódź in literature and cinema

Three major novels depict the development of industrial Łódź: Władysław Reymont's The Promised Land (1898), Joseph Roth's Hotel Savoy (1924) and Israel Joshua Singer's The Brothers Ashkenazi (1937). Roth's novel depicts the city on the eve of a workers' riot in 1919. Reymont's novel was made into a film by Andrzej Wajda in 1975. In the 1990 film Europa Europa, Solomon Perel's family flees pre-WWII Berlin and settles in Łódź. Scenes of David Lynch's 2006 film Inland Empire were shot in Łódź. Pawel Pawlikowski's film Ida (film) was partially shot in Łódź. Sections of Harry Turtledove's Worldwar alternate history series take place in Łódź.

Sports

Under communism it was common for clubs to participate in many different sports for all ages and sexes. Many of these traditional clubs still survive today. Originally they were owned directly by a public body, but now they are independently operated by clubs or private companies. However they get public support through the cheap rent of land and other subsidies from the city. Some of their sections have gone professional and separated from the clubs as private companies. For example Budowlani S.A is a private company that owns the only professional rugby team in Łódź, while Klub Sportowy Budowlani remains a community amateur club.

- Budowlani Łódź- Rugby, Hockey, Wrestling, Volleyball.

- ŁKS Łódź - Association football, basketball, volleyball, handball, boxing.

- SMS Łódź[17] - Association football, Volleyball, Basketball,

- KS Społem Łódź – road and track cycling.

- SKS Start Łódź[18] - Football, Swimnming.

- Widzew Łódź - Association football

Government

Mayor

- Waldemar Bohdanowicz, Solidarity (November 1989 – 1990) – appointed by Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki.

- Grzegorz Palka (1990–1994)

- Marek Czekalski, Freedom Union (1994–1998)

- Tadeusz Matusiak, SLD (1998–2001)

- Krzysztof Panas, SLD (2001–2002)

- Krzysztof Jagiełło, SLD (2002)

- Jerzy Kropiwnicki, Christian-National Union (ZChN) (2002–2010)

- Tomasz Sadzyński, Platforma Obywatelska / Civic Platform (temporary in 2010)

- Hanna Zdanowska, Platforma Obywatelska / Civic Platform

International relations

Łódź is home to nine foreign consulates, all of which are Honorary. They are subordinate to the following states main representation in Poland: French, Danish, German, Austrian, British, Belgian, Latvian, Hungarian and Moldavian.

Twin towns – sister cities

|

|

Łódź belongs also to the Eurocities network.

Notable residents

- Daniel Amit, Israeli physicist

- Grażyna Bacewicz, composer

- Aleksander Bardini, stage director and actor

- Andrzej Bartkowiak, cameraman and film director

- Jurek Becker (1937–1997) writer

- Kazimierz Brandys, writer

- Artur Brauner, film producer

- Jacob Bronowski, writer, mathematician, and Britain's leading academic TV figure of the 1970s.

- Sabina Citron, Holocaust survivor, activist, and author

- Karl Dedecius, translator

- Karl Dominik (Born:Karol Dominik Ignaczak), China's first Chinese speaking Polish actor

- Max Factor, Sr., businessman, founder of the Max Factor cosmetics company

- Dov Freiberg, Holocaust survivor and writer

- Piotr Fronczewski, Polish actor

- Marcin Gortat, NBA basketball player for the Washington Wizards

- Mendel Grossman, Łódź ghetto photographer [26]

- Józef Hecht (1891–1951), engraver and printmaker

- Josef Joffe, journalist

- Jan Karski, diplomat and antinazi resistant

- Aharon Katzir (1914–1972), Israeli pioneer in study of electrochemistry of biopolymers; killed in Lod Airport Massacre

- Lea Koenig, Israeli actress

- Paul Klecki, conductor

- Katarzyna Kobro, sculptor

- Jerzy Kosinski, writer

- Jan Kowalewski, Polish cryptologist who broke Soviet military codes and ciphers during the Polish-Soviet War

- Feliks W. Kres, fantasy writer

- Nathan Lewin, Washington, D.C. attorney

- Daniel Libeskind, architect

- Tadeusz Miciński, poet

- Zew Wawa Morejno, Chief Rabbi

- Zbigniew Nienacki, writer

- Marian P. Opala, Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice

- Adam Ostrowski, better known as O.S.T.R., rapper

- Władysław Pasikowski, director

- Roman Polanski, cinema director, Oscar and Golden Palm winner

- Piotr Pustelnik, Polish alpine and high-altitude climber, the 20th man to climb all fourteen eight-thousanders.

- Zbigniew Rybczyński, animator and Oscar winner

- Władysław Reymont, writer, Nobel Prize winner

- Joseph Rotblat, Nobel Prize winner

- Stefan Rozental, nuclear physicist

- Arnold Rutkowski, opera singer

- Artur Rubinstein, pianist, settled

- Marek Saganowski, football player

- Andrzej Sapkowski, fantasy writer

- Carl Wilhelm Scheibler (1820–1881) one of the most important Łódź industrialists

- Piotr Sobociński, cinematographer

- Andrzej Sontag, track-and-field star

- Natan Spigel, painter (1900–1942)

- Władysław Strzemiński, painter, Kobro's husband

- Arthur Szyk, artist

- Aleksander Tansman, composer and pianist

- Jack Tramiel, computer manufacturer, founder of Commodore and Atari

- Julian Tuwim, poet

- Miś Uszatek, cartoon character

- Michał Wiśniewski, singer

- Hanna Zdanowska, politician

- Aleksandra Ziółkowska-Boehm, writer

- Jerzy Janowicz, Tennis player

Notable descendants of Łódź residents

- Ben Burns, American editor of African American publications

- Amy Totenberg, American district judge

- Nina Totenberg, American NPR legal affairs correspondent

- Barbara Walters, American journalist, author, and television personality

- Ada Yonath, Israeli crystallographer and Nobel laureate

Points of interest

-

Łódź City Hall, formerly Heinzel Palace

-

Old Town square

-

European Institute, formerly Schweikert Palace

-

Andel's Hotel, near Manufaktura shopping mall

-

Music Academy, formerly Poznanski Palace

-

White Factory

-

Great Synagogue (Łódź) destroyed by Nazi Germans

-

Sigillum oppidi Lodzia, 1577

-

Izrael Poznanski's Palace

-

Karol Scheibler's chapel, Old Evangelical–Augsburg church and cemetery

-

.jpg)

Concert hall

-

Poniatowski's Park

-

Planned motorway network around Łódź

-

(LCJ) Łódź Airport

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lodz Merriam-Webster online.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wiesław Puś, Stefan Pytlas. "Industry and Trade in Łódź and the Eastern Markets in Partitioned Poland". In: Uwe Müller, Helga Schultz. National borders and economic disintegration in modern East Central Europe. Berlin Verlag A. Spitz. 2002. p. 69.

- ↑ "Neues Leben in alten Fabriken: Lódz baut auf Kultur" (in German). Weser Kurier. 22 September 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ↑ "Foundation For Saving Karol Scheibler's Chapel". Scheibler.org.pl. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ↑ Joshua D. Zimmerman, Poles, Jews, and the politics of nationality, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2004, ISBN 0-299-19464-7, Google Print, p.16

- ↑ Robert Bubczyk. A History of Poland in Outline. Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Press. 2002. p. 68.

- ↑ Gordon J Horwitz. Ghettostadt: Łódź and the Making of a Nazi City. Harvard University Press. 2009. p. 3.

- ↑ Isaiah Trunk: 2006, Page xi

- ↑ Weiner, Rebecca. The Virtual Jewish History Tour. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Retrieved on 15 January 2008.

- ↑ Blobaum, Robert. "On Strike on Łódź. "Rewolucja: Russian Poland, 1904–1907". Cornell University Press, 1995. p. 75.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 (AFP)–24 Jan 2009 (24 January 2009). "AFP: Dell seeks refuge in Poland as crisis bites". Google.com. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- ↑ "The New Cemetery in Lodz". Lodz ShtetLinks. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "JEWISH CEMETERY". FUNDACJA MONUMENTUM IUDAICUM LODZENSE. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "Cmentarz żydowski w Łodzi zdewastowany [ZDJĘCIA+FILM]". Dziennik LODZKI. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ↑ http://www.studenckinobel.pl/index.php/historia-konkursu History of the contest "Studencki Nobel" (in Polish)

- ↑ "Młody dziennikarz znów pretenduje do Nobla! (in Polish)". Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ↑ http://www.smslodz.pl/

- ↑ http://www.sksstart.com/

- ↑ "Twin Cities". The City of Łódź Office.

(in English and Polish) copyright 2007 UMŁ. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

(in English and Polish) copyright 2007 UMŁ. Retrieved 23 October 2008. - ↑ "Stuttgart Städtepartnerschaften". Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart, Abteilung Außenbeziehungen (in German). Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- ↑ "Partner Cities of Lyon and Greater Lyon". copyright 2008 Mairie de Lyon. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ↑ "Kaliningrad -Partner Cities". copyright 2000–2006 Kaliningrad City Hall. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ↑ "Twin towns and Sister cities of Minsk [via WaybackMachine.com]" (in Russian). The department of protocol and international relations of Minsk City Executive Committee. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- ↑ "Tel Aviv sister cities" (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ↑ Vänorter – orebro.se

- ↑ Holocaust chronicles... – Google Books. Books.google.com. May 1999. ISBN 978-0-88125-630-7. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- Horwitz, Gordon J. (2008). Ghettostadt: Łódź and the making of a Nazi city. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 978-0-674-02799-2. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- Stefański, Krzysztof (2000). Gmachy użyteczności publicznej dawnej Łodzi, Łódź 2000 ISBN 83-86699-45-0.

- Stefański, Krzysztof (2009). Ludzie którzy zbudowali Łódź Leksykon architektów i budowniczych miasta (do 1939 roku), Łódź 2009 ISBN 978-83-61253-44-0.

- Trunk, Isaiah; Shapiro, Robert Moses (2006). Łódź Ghetto: a history. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana. ISBN 978-0-253-34755-8. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

Bibliography

- Gordon J. Horwitz, Ghettostadt: Łódź and the Making of a Nazi City Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 0674038797

- "A Stairwell in Lodz," Constance Cappel, 2004, Xlibris, (in English).

- "Lodz – The Last Ghetto in Poland," Michal Unger, Yad Vashem, 600 pages (in Hebrew)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Łódź. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Łódź. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Lodz. |

- Official website

- Public Transport Official Site

- City map of Łódź

- Historic images of Łódź

- Photo Gallery of Łódź

- Łódź Special Economic Zone

- Łódź-Lublinek Airport

- The Lodz English language newspaper

- The Łódź Ghetto

- Youth Groups in the Łódź Ghetto – Online Exhibition from Yad Vashem

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

.png)