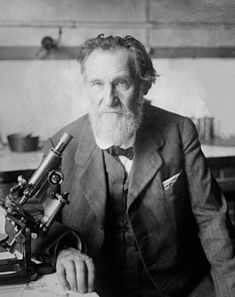

Élie Metchnikoff

| Élie Metchnikoff | |

|---|---|

|

Élie Metchnikoff, c. 1908 | |

| Born |

Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov 16 May [O.S. 3 May] 1845 Ivanovka, Kharkov Governorate, Russian Empire (now Kupiansk Raion, Kharkiv Oblast, Ukraine) |

| Died |

16 July 1916 (aged 71) Paris, France |

| Nationality | Russian Empire |

| Fields | |

| Institutions |

Odessa University University of St. Petersburg Pasteur Institute |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | Phagocytosis |

| Notable awards |

Copley Medal (1906) Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1908) Albert Medal (1916) |

Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (Russian: Илья́ Ильи́ч Ме́чников, also seen as Élie Metchnikoff) (16 May [O.S. 3 May] 1845 – 16 July 1916) was a Russian zoologist best known for his pioneering research into the immune system.[1] In particular, he is credited with the discovery of phagocytes (macrophages) in 1882, and his discovery turned out to be the major defence mechanism in innate immunity.[2] He and Paul Ehrlich were awarded the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "in recognition of their work on immunity".[3] He is also credited by some sources with coining the term gerontology in 1903, for the emerging study of aging and longevity.[4][5] He established the concept of cell-mediated immunity, while Ehrlich that of humoral immunity. Their works are regarded as the foundation of the science of immunology.[6] In immunology he is given an epithet the "father of natural immunity".[7]

Life and work

Mechnikov was born in the village Panasovka (or Ivanovka) near Kharkov (now Kharkiv in Ukraine), Russian Empire. He was the youngest of five children of Ilya Ivanovich Mechnikov, an officer of the Imperial Guard.[1] His mother, Emilia Lvovna (Nevakhovich), the daughter of the Jewish writer Leo Nevakhovich, largely influenced him on his education, especially in science.[8][9] The family name Mechnikov is a translation from Romanian, since his father was a descendant of the Chancellor Yuri Stefanovich, the grandson of Nicolae Milescu. The word "mech" is a Russian translation of the Romanian "spadă" (sword), which originated with Spătar. His elder brother Lev became a prominent geographer and sociologist.[10]

He entered Kharkov Lycée in 1856 and developed his interest in biology. Convinced by his mother to study natural sciences instead of medicine, in 1862 he tried to study biology at the University of Würzburg. But the German academic session would not start by the end of the year. So he enrolled at Kharkiv University for natural sciences, completing his four-year degree in two years. In 1864 he went to Germany to study marine fauna on the small North Sea island of Heligoland. He was advised by the botanist Ferdinand Cohn to work with Rudolf Leuckart at the University of Giessen. It was in Leuckart’s laboratory that he made his first scientific discovery of alternation of generations (sexual and asexual) in nematodes. and then at Munich Academy. In 1865, while at Giessen, he discovered intracellular digestion in flatworm, and this study influenced his later works. Moving to Naples the next year he worked on a doctoral thesis on the embryonic development of the cuttle-fish Sepiola and the crustacean Nelalia. A cholera epidemic in the autumn of 1865 made him move to the University of Göttingen, where we worked briefly with W. M. Keferstein and Jakob Henle. In 1867 he returned to Russia to get his doctorate with Alexander Kovalevsky from the University of St. Petersburg. Together they won the Karl Ernst von Baer prize for their theses on the development of germ layers in invertebrate embryos. Mechnikov was appointed docent at the newly established Imperial Novorossiya University (now Odessa University). Only twenty-two years of age, he was younger than his students. After involving in a conflict with senior colleague over attending scientific meeting, in 1868 he transferred to the University of St. Petersburg, where he experienced a worse professional environment. In 1870 he returned to Odessa to take up the appointment of Titular Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy.[8][1]

In 1882 he resigned from Odessa University due to political turmoils after the assassination of Alexander II. He went to Messina to set up his private laboratory. He returned to Odessa as director of an institute set up to carry out Louis Pasteur's vaccine against rabies, but due to some difficulties left in 1888 and went to Paris to seek Pasteur's advice. Pasteur gave him an appointment at the Pasteur Institute, where he remained for the rest of his life.[1]

Research

Mechnikov became interested in the study of microbes, and especially the immune system. At Messina he discovered phagocytosis after experimenting on the larvae of starfish. In 1882 he first demonstrated the process when he pinned small thorns into starfish larvae, and he found unusual cells surrounding the thorns. The thorns were from a tangerine tree made into Christmas tree. He realized that in animals which have blood, the white blood cells gather at the site of inflammation, and he hypothesised that this could be the process by which bacteria were attacked and killed by the white blood cells. He discussed his hypothesis with Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Claus, Professor of Zoology at the University of Vienna, who suggested him the term "phagocyte" for cell which can surround and kill pathogens. He delivered his findings at Odessa University in 1883.[1]

His theory, that certain white blood cells could engulf and destroy harmful bodies such as bacteria, met with scepticism from leading specialists including Louis Pasteur, Behring and others. At the time most bacteriologists believed that white blood cells ingested pathogens and then spread them further through the body. His major supporter was Rudolf Virchow who published his research in his Arehiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medizin (now called the Virchows Archiv).[8] His discovery of these phagocytes ultimately won him the Nobel Prize in 1908. He worked with Émile Roux on calomel, an ointment to prevent people from contracting syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease.[3]

Mechnikov also developed a theory that aging is caused by toxic bacteria in the gut and that lactic acid could prolong life. Based on this theory, he drank sour milk every day. He wrote The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies, in which he espoused the potential life-lengthening properties of lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus).[11][12] He attributed the longevity of Bulgarian peasants due to their yogurt consumption.[13] This later inspired Japanese scientist Minoru Shirota to begin investigating a causal relationship between bacteria and good intestinal health, which eventually led to the worldwide marketing of Yakult, kefir and other fermented milk drinks, or probiotics.[14][15]

Death

Mechnikov died in 1916 in Paris from heart failure.[16]

Personal life and views

Mechnikov was married to his first wife Ludmila Feodorovitch in 1863. She died from tuberculosis on 20 April 1873. Her death, combined with other problems, caused Mechnikov to unsuccessfully attempt suicide, taking a large dose of opium. In 1875 he married his young student Olga Belokopytova.[7] In 1885 Olga suffered from severe typhoid and this caused him to attempt his second but failed suicide.[1] He injected himself with the spirochete of relapsing fever. (Olga died in 1944 in Paris from typhoid.)[8]

He was greatly influenced by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. He first read Fritz Müller's Für Darwin (For Darwin) in Giessen. From this he became a supporter of natural selection and Ernst Haeckel's biogenetic law.[18] His scientific works and theories were inspired by Darwinism.[19]

Awards and recognitions

Mechnikov with Alexander Kovalevsky won the Karl Ernst von Baer prize in 1867 based on their doctoral research. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1908 with Paul Ehrlich . He was awarded honorary degree from the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, UK, and the Copley Medal of the Royal Society in 1906. He was given honorary memberships in the Academy of Medicine in Paris and the Academy of Sciences and Medicine in St. Petersburg.[18] The Leningrad Medical Institute of Hygiene and Sanitation, founded in 1911 was merged with Saint Petersburg State Medical Academy of Postgraduate Studies in 2011 to become the North-Western State Medical University named after I.I. Mechnikov.[20][21] There is Odessa I.I. Mechnikov National University in Odessa, Ukraine.[22]

Books

Metchnikoff wrote notable books such as:[2][7]

- Leçons sur la pathologie comparée de l’inflammation (1892; Lectures on the Comparative Pathology of Inflammation)

- L’Immunité dans les maladies infectieuses (1901; Immunity in Infectious Diseases)

- Études sur la nature humaine (1903; The Nature of Man)

- Immunity in Infective Diseases (1905)

- The New Hygiene: Three Lectures on the Prevention of Infectious Diseases (1906)

- The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies (1907)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "Ilya Mechnikov - Biographical". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Élie Metchnikoff". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1908". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Vértes, L (1985). "The gerontologist Mechnikov". Orvosi hetilap 126 (30): 1859–1860. PMID 3895124.

- ↑ Martin, D. J.; Gillen, L. L. (2013). "Revisiting Gerontology's Scrapbook: From Metchnikoff to the Spectrum Model of Aging". The Gerontologist 54 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt073. PMID 23893558.

- ↑ Kaufmann, Stefan H E (2008). "Immunology's foundation: the 100-year anniversary of the Nobel Prize to Paul Ehrlich and Elie Metchnikoff". Nature Immunology 9 (7): 705–712. doi:10.1038/ni0708-705. PMID 18563076.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Gordon, Siamon (2008). "Elie Metchnikoff: Father of natural immunity". European Journal of Immunology 38 (12): 3257–3264. doi:10.1002/eji.200838855. PMID 19039772.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Metchnikoff, Elie". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ http://archive.org/stream/lifeofeliemetchn00metciala/lifeofeliemetchn00metciala_djvu.txt

- ↑ White, James D (1976). "Despotism and Anarchy: The Sociological Thought of L. I. Mechnikov". The Slavonic and East European Review 54 (3): 395–411. JSTOR 4207300.

- ↑ Mackowiak, Philip A. (2013). "Recycling Metchnikoff: Probiotics, the Intestinal Microbiome and the Quest for Long Life". Frontiers in Public Health 1: 52. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2013.00052. PMC 3859987. PMID 24350221.

- ↑ Podolsky, Scott H (2012). "Metchnikoff and the microbiome". The Lancet 380 (9856): 1810–1811. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62018-2. PMID 23189332.

- ↑ Brown, AC; Valiere, A (2004). "Probiotics and medical nutrition therapy". Nutrition in Clinical Care 7 (2): 56–68. PMC 1482314. PMID 15481739.

- ↑ Sutula, Justyna; Ann Coulthwaite, Lisa; Thomas, Linda Valerie; Verran, Joanna (2013). "The effect of a commercial probiotic drink containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on oral health in healthy dentate people". Microbial Ecology in Health & Disease 24 (online). doi:10.3402/mehd.v24i0.21003. PMC 3813825. PMID 24179468.

- ↑ Douillard, François P.; Kant, Ravi; Ritari, Jarmo; Paulin, Lars; Palva, Airi; de Vos, Willem M. (2013). "Comparative genome analysis of Lactobacillus casei strains isolated from Actimel and Yakult products reveals marked similarities and points to a common origin". Microbial Biotechnology 6 (5): 576–587. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.12062.

- ↑ B. I. Goldstein (21 July 1916). "Elie Metchnikoff". Canadian Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ↑ Alfred I. Tauber Professor of Medicine and Pathology, Leon Chernyak Research Associate both of Boston University School of Medicine (1991). Metchnikoff and the Origins of Immunology : From Metaphor to Theory: From Metaphor to Theory. Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780195345100.

There is no clear record that he was professionally restricted in Russia because of his lineage, but he sympathized with the problem his Jewish colleagues suffered owing to Russian anti-Semitism; his personal religious commitment was to atheism, although he received strict Christian religious training at home. Metchnikoff's atheism smacked of religious fervor in the embrace of rationalism and science. We may fairly argue that Metchnikoff's religion was based on the belief that rational scientific discourse was the solution for human suffering.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (Elie Metchnikoff) (1845-1916)". The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Thomas F., Glick (1988). The Comparative Reception of Darwinism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-226-29977-8.

- ↑ "North-Western State Medical University I.I. Mechnikov". FAIMER. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "North-Western State Medical University named after I.I. Mechnikov". North-Western State Medical University named after I.I. Mechnikov. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Odessa I.I. Mechnikov national university". Odessa I.I. Mechnikov national university. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

Further reading

- Breathnach, C S (September 1984). "Biographical sketches—No. 44. Metchnikoff". Irish medical journal (Ireland) 77 (9): 303. ISSN 0332-3102. PMID 6384135.

- de Kruif, Paul (1996). Microbe Hunters. San Diego: A Harvest Book. ISBN 978-0-15602-777-9.

- Deutsch, Ronald M. (1977). The new nuts among the berries. Palo Alto, CA: Bull Pub. Co. ISBN 0-915950-08-1.

- Fokin, Sergei I. (2008). Russian scientists at the Naples zoological station, 1874 - 1934. Napoli: Giannini. ISBN 978-8-8743-1404-1.

- Gourko, Helena; Williamson, Donald I.; Tauber, Alfred I. (2000). The Evolutionary Biology Papers of Elie Metchnikoff. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. ISBN 978-94-015-9381-6.

- Karnovsky, M L (May 1981). "Metchnikoff in Messina: a century of studies on phagocytosis". N. Engl. J. Med. (United States) 304 (19): 1178–80. doi:10.1056/NEJM198105073041923. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 7012622.

- Lavrova, L N (September 1970). "[I. I. Mechnikov and the significance of his legacy for the development of Soviet science (on the 125th anniversary of his birth)]". Zh. Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. (USSR) 47 (9): 3–5. ISSN 0372-9311. PMID 4932822.

- Schmalstieg Frank C, Goldman Armond S (2008). "Ilya Ilich Metchnikoff (1845–1915) and Paul Ehrlich (1854–1915) The centennial of the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine". Journal of Medical Biography 16 (2): 96–103. doi:10.1258/jmb.2008.008006. PMID 18463079.

- Tauber, Alfred I.; Chernyak, Leon (1991). Metchnikoff and the Origins of Immunology : from Metaphor to Theory. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506447-X.

- Tauber AI (2003). "Metchnikoff and the phagocytosis theory". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 4: 897–901. doi:10.1038/nrm1244.

- Zalkind, Semyon (2001) [1957]. Ilya Mechnikov: His Life and Work. The Minerva Group, Inc. ISBN 0-89875-622-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov. |

- NNDB profile

- The Romantic Rationalist: A Study Of Elie Metchnikoff

- Books written by I.I.Mechnikov (In Russian)

- Lactobacillus bulgaricus on the web

- Tsalyk St. Immunity defender

- Immunity in Infective Diseases (1905) by Élie Metchnikoff, translated by Francis B. Binny, on the Internet Archive

- The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies (1908) by Élie Metchnikoff, translation edited by P. Chalmers Mitchell, on the Internet Archive

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|