Yuktibhāṣā

Yuktibhāṣā (Malayalam: യുക്തിഭാഷ; "Rationale in the Malayalam/Sanskrit language"[1]) also known as Gaṇitanyāyasaṅgraha ("Compendium of astronomical rationale"),[1] is a major treatise on mathematics and astronomy, written by Indian astronomer Jyesthadeva of the Kerala school of mathematics in about AD 1530.[1] The treatise is a consolidation of the discoveries by Madhava of Sangamagrama, Nilakantha Somayaji, Parameshvara, Jyeshtadeva, Achyuta Pisharati and other astronomer-mathematicians of the Kerala school. Yuktibhasa is mainly based on Nilakantha's Tantra Samgraha.[2] It is considered an early text on some of the foundations of calculus and predates those of European mathematicians such as James Gregory by over a century.[3][4][5][6] However, the treatise was largely unnoticed beyond Kerala, as the book was written in the local language of Malayalam. However, some have argued that mathematics from Kerala were transmitted to Europe (see Possible transmission of Keralese mathematics to Europe).

The work was unique for its time, since it contained proofs and derivations of the theorems that it presented; something that was not usually done by any Indian mathematicians of that era.[7] Some of its important developments in analysis include: the infinite series expansion of a function, the power series, the Taylor series, the trigonometric series for sine, cosine, tangent and arctangent, the second and third order Taylor series approximations of sine and cosine, the power series of π, π/4, θ, the radius, diameter and circumference, and tests of convergence.

Contents

Yuktibhasa contains most of the developments of earlier Kerala School mathematicians, particularly Madhava and Nilakantha. The text is divided into two parts — the former deals with mathematical analysis of arithmetic, algebra, trigonometry and geometry, logistics, algebraic problems, fractions, Rule of three, Kuttakaram, circle and disquisition on R-Sine; and the latter about astronomy.[1]

Mathematics

As per the old Indian tradition of starting off new chapters with elementary content, the first four chapters of the Yuktibhasa contain elementary mathematics, such as division, proof of Pythagorean theorem, square root determination, etc.[8] The radical ideas are not discussed until the sixth chapter on circumference of a circle. Yuktibhasa contains the derivation and proof of the power series for inverse tangent, discovered by Madhava.[2] In the text, Jyesthadeva describes Madhava's series in the following manner:

| “ | The first term is the product of the given sine and radius of the desired arc divided by the cosine of the arc. The succeeding terms are obtained by a process of iteration when the first term is repeatedly multiplied by the square of the sine and divided by the square of the cosine. All the terms are then divided by the odd numbers 1, 3, 5, .... The arc is obtained by adding and subtracting respectively the terms of odd rank and those of even rank. It is laid down that the sine of the arc or that of its complement whichever is the smaller should be taken here as the given sine. Otherwise the terms obtained by this above iteration will not tend to the vanishing magnitude. | ” |

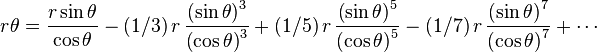

This yields

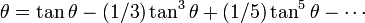

which further yields the theorem

attributed to James Gregory, who discovered it three centuries after Madhava.

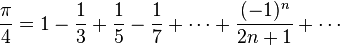

The text also elucidates Madhava's infinite series expansion of π:

which he obtained from the power series expansion of the arc-tangent function.

Using a rational approximation of this series, he gave values of the number π as 3.14159265359 - correct to 11 decimals; and as 3.1415926535898 - correct to 13 decimals. These were the most accurate approximations of π after almost a thousand years.[citation needed]

The text describes that he gave two methods for computing the value of π.

- One of these methods is to obtain a rapidly converging series by transforming the original infinite series of π. By doing so, he obtained the infinite series

and used the first 21 terms to compute an approximation of π correct to 11 decimal places as 3.14159265359.

- The other method was to add a remainder term to the original series of π. The remainder term was used

in the infinite series expansion of  to improve the approximation of π to 13 decimal places of accuracy when n = 76.

to improve the approximation of π to 13 decimal places of accuracy when n = 76.

Apart from these, the Yukthibhasa contains many elementary, and complex mathematics, including,

- Proof for the expansion of the sine and cosine functions.

- Integer solutions of systems of first degree equations (solved using a system known as kuttakaram)

- Rules for finding the sines and the cosines of the sum and difference of two angles.

- The earliest statement of and the Taylor series (only some for some functions).

- Geometric derivations of series.

- Tests of convergence (often attributed to Cauchy)

- Fundamentals of calculus:[5] differentiation, term by term integration, iterative methods for solutions of non-linear equations, and the theory that the area under a curve is its integral.

Most of these results were long before their European counterparts, to whom credit was traditionally attributed.

Astronomy

Chapters seven to seventeen of the text deals essentially with subjects of astronomy, viz. Planetary orbit, Celestial sphere, ascension, declination, directions and shadows, spherical triangles, ellipses and parallax correction. The planetary theory described in the book is similar to that later adopted by Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe.[9]

Modern edition of Yuktibhasa

The importance of Yuktibhasa was brought to the attention of modern scholarship by C.M. Whish in 1834 through a paper published in the Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. However, an edition of the mathematics part of the text (along with notes in Malayalam) was published only in 1948 by Ramavarma Thampuran and Akhileswara Aiyar. For the first time, a critical edition of the entire Malayalam text, along with English translation and detailed explanatory notes, has been brought out in two volumes by Springer in 2008.[10] A third volume presenting a critical edition of the Sanskrit Ganitayuktibhasa has been brought out by the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla in 2009.[11]

See also

- Ganita-yukti-bhasa

- Indian mathematics

- Kerala School

- Possible transmission of Kerala mathematics to Europe

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 K V Sarma; S Hariharan (1991). "Yuktibhāṣā of Jyeṣṭhadeva: A book on rationales in Indian Mathematics and Astronomy: An analytic appraisal" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science 26 (2). Archived from the original on 2006-09-28. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The Kerala School, European Mathematics and Navigation". Indian Mathemematics. D.P. Agrawal — Infinity Foundation. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ "Neither Newton nor Leibniz - The Pre-History of Calculus and Celestial Mechanics in Medieval Kerala". MAT 314. Canisius College. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ "An overview of Indian mathematics". Indian Maths. School of Mathematics and Statistics University of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 2006-07-07.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Science and technology in free India" (PDF). Government of Kerala — Kerala Call, September 2004. Prof.C.G.Ramachandran Nair. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ Charles Whish (1834), "On the Hindu Quadrature of the circle and the infinite series of the proportion of the circumference to the diameter exhibited in the four Sastras, the Tantra Sahgraham, Yucti Bhasha, Carana Padhati and Sadratnamala", Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland) 3 (3): 509–523, doi:10.1017/S0950473700001221, JSTOR 25581775

- ↑ "Jyesthadeva". Biography of Jyesthadeva. School of Mathematics and Statistics University of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 2006-07-07.

- ↑ "The Yuktibhasa Calculus Text" (PDF). The Pre-History of Calculus and Celestial Mechanics in Medieval Kerala. Dr Sarada Rajeev. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ "Science and Mathematics in India". South Asian history. India Resources. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ Sarma, K.V.; Ramasubramanian, K., Srinivas, M.D., Sriram, M.S. (2008). Ganita-Yukti-Bhasa (Rationales in Mathematical Astronomy) of Jyesthadeva. Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. Volume I: Mathematics Volume II: Astronomy (1 ed.). Springer (jointly with Hindustan Book Agency, New Delhi). pp. LXVIII, 1084. ISBN 978-1-84882-072-2. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ↑ Sarma, K.V. (2009). Ganita Yuktibhasa (in Malayalam and English). Volume III. Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla, India. ISBN 81-7986-052-3. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

References

- K V Sharma & S Hariharan (1990). Yuktibhasa of Jyesthadeva — A book on rationales in Indian Mathematics and Astronomy - an analytic appraisal. Indian Journal of History of Science.