Yeoh (hyperelastic model)

The Yeoh hyperelastic material model[1] is a phenomenological model for the deformation of nearly incompressible, nonlinear elastic materials such as rubber. The model is based on Ronald Rivlin's observation that the elastic properties of rubber may be described using a strain energy density function which is a power series in the strain invariants  .[2] The Yeoh model for incompressible rubber is a function only of

.[2] The Yeoh model for incompressible rubber is a function only of  . For compressible rubbers, a dependence on

. For compressible rubbers, a dependence on  is added on. Since a polynomial form of the strain energy density function is used but all the three invariants of the left Cauchy-Green deformation tensor are not, the Yeoh model is also called the reduced polynomial model.

is added on. Since a polynomial form of the strain energy density function is used but all the three invariants of the left Cauchy-Green deformation tensor are not, the Yeoh model is also called the reduced polynomial model.

Yeoh model for incompressible rubbers

Strain energy density function

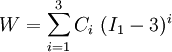

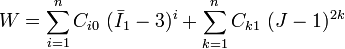

The original model proposed by Yeoh had a cubic form with only  dependence and is applicable to purely incompressible materials. The strain energy density for this model is written as

dependence and is applicable to purely incompressible materials. The strain energy density for this model is written as

where  are material constants. The quantity

are material constants. The quantity  can be interpreted as the initial shear modulus.

can be interpreted as the initial shear modulus.

Today a slightly more generalized version of the Yeoh model is used.[3] This model includes  terms and is written as

terms and is written as

When  the Yeoh model reduces to the neo-Hookean model for incompressible materials.

the Yeoh model reduces to the neo-Hookean model for incompressible materials.

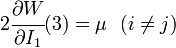

For consistency with linear elasticity the Yeoh model has to satisfy the condition

where  is the shear modulus of the material.

Now, at

is the shear modulus of the material.

Now, at  ,

,

Therefore, the consistency condition for the Yeoh model is

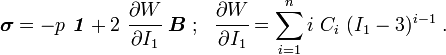

Stress-deformation relations

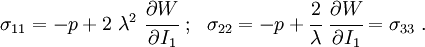

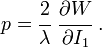

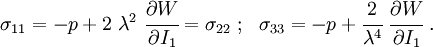

The Cauchy stress for the incompressible Yeoh model is given by

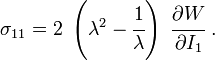

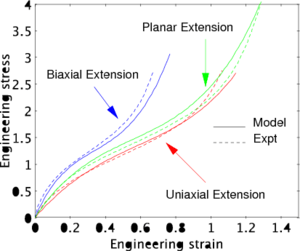

Uniaxial extension

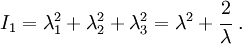

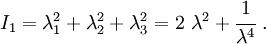

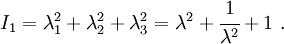

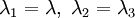

For uniaxial extension in the  -direction, the principal stretches are

-direction, the principal stretches are  . From incompressibility

. From incompressibility  . Hence

. Hence  .

Therefore,

.

Therefore,

The left Cauchy-Green deformation tensor can then be expressed as

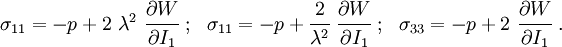

If the directions of the principal stretches are oriented with the coordinate basis vectors, we have

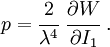

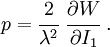

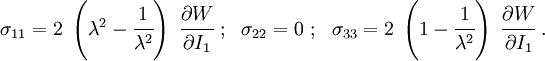

Since  , we have

, we have

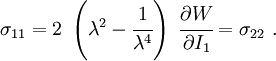

Therefore,

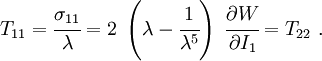

The engineering strain is  . The engineering stress is

. The engineering stress is

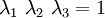

Equibiaxial extension

For equibiaxial extension in the  and

and  directions, the principal stretches are

directions, the principal stretches are  . From incompressibility

. From incompressibility  . Hence

. Hence  .

Therefore,

.

Therefore,

The left Cauchy-Green deformation tensor can then be expressed as

If the directions of the principal stretches are oriented with the coordinate basis vectors, we have

Since  , we have

, we have

Therefore,

The engineering strain is  . The engineering stress is

. The engineering stress is

Planar extension

Planar extension tests are carried out on thin specimens which are constrained from deforming in one direction. For planar extension in the  directions with the

directions with the  direction constrained, the principal stretches are

direction constrained, the principal stretches are  . From incompressibility

. From incompressibility  . Hence

. Hence  .

Therefore,

.

Therefore,

The left Cauchy-Green deformation tensor can then be expressed as

If the directions of the principal stretches are oriented with the coordinate basis vectors, we have

Since  , we have

, we have

Therefore,

The engineering strain is  . The engineering stress is

. The engineering stress is

Yeoh model for compressible rubbers

A version of the Yeoh model that includes  dependence is used for compressible rubbers. The strain energy density function for this model is written as

dependence is used for compressible rubbers. The strain energy density function for this model is written as

where  , and

, and  are material constants. The quantity

are material constants. The quantity  is interpreted as half the initial shear modulus, while

is interpreted as half the initial shear modulus, while  is interpreted as half the initial bulk modulus.

is interpreted as half the initial bulk modulus.

When  the compressible Yeoh model reduces to the neo-Hookean model for incompressible materials.

the compressible Yeoh model reduces to the neo-Hookean model for incompressible materials.

References

- ↑ Yeoh, O. H., 1993, "Some forms of the strain energy function for rubber," Rubber Chemistry and technology, Volume 66, Issue 5, November 1993, Pages 754-771.

- ↑ Rivlin, R. S., 1948, "Some applications of elasticity theory to rubber engineering", in Collected Papers of R. S. Rivlin vol. 1 and 2, Springer, 1997.

- ↑ Selvadurai, A. P. S., 2006, "Deflections of a rubber membrane", Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, vol. 54, no. 6, pp. 1093-1119.

See also

- Hyperelastic material

- Strain energy density function

- Mooney-Rivlin solid

- Finite strain theory

- Stress measures