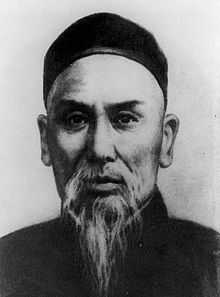

Yang Lu-ch'an

| Yang Luchan <span class="nickname"lang="Chinese" xml:lang="Chinese">杨露禅 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1799 Guangping, China |

| Died | 1872 (aged 72–73) |

| Native name | 杨露禅 |

| Other names |

Yang Fukui, Yang Wudi |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Style | Yang-style taijiquan |

| Teacher(s) | Chen Changxing |

| Rank | Founder of Yang-style taijiquan |

| Notable students |

Yang Banhou, Yang Jianhou, Wu Yuxiang, Wang Lanting (王蘭亭) |

| Yang Lu-ch'an | |||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 杨露禅 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 楊露禪 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Yang Fukui | |||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 杨福魁 | ||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 楊福魁 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Yang Wudi | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 楊無敵 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Yang the Invincible | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese martial arts (Wushu) |

|---|

|

|

Styles of Chinese martial arts

|

| Wushu in the world |

|

Historical locations Chen Village (陳家溝) |

| Wushu artists |

|

Legendary figures Bodhidharma (菩提達摩) |

|

Historical individuals Yue Fei (岳飛; 1103—1142) |

|

Modern celebrities Bruce Lee (李小龍 1940—1973) |

| Wushu influence |

|

Related |

Yang Lu-ch'an or Yang Luchan, also known as Yang Fu-k'ui or Yang Fukui (1799-1872), born in Kuang-p'ing (Guangping), was an influential teacher of the internal style martial art t'ai chi ch'uan (taijiquan) in China during the second half of the 19th century. He is known as the founder of Yang-style t'ai chi ch'uan.[1][2]

History

Yang Lu-ch'an’s family was a poor farming/worker class from Hebei Province, Guangping Prefecture, Yongnian County. Yang would follow his father in planting the fields and, as a teenager, held temporary jobs. One period of temporary work was spent doing odd jobs at the Tai He Tang Chinese pharmacy located in the west part of Yongnian City, opened by Chen De Hu of the Chen Village in Henan Province, Huaiqing Prefecture, Wenxian County. As a child, Yang liked martial arts and studied Changquan, gaining a certain level of skill.

One day Yang reportedly witnessed one of the partners of the pharmacy utilizing a style of martial art that he had never before seen to easily subdue a group of would-be thieves. Because of this, Yang requested to study with the pharmacy's owner, Chen De Hu. Chen referred Yang to the Chen Village to seek out his own teacher—the 14th generation of the Chen Family, Ch'en Chang-hsing.[1][2][3]

After mastering the martial art, Yang Lu-ch'an was subsequently given permission by his teacher to go to Beijing and teach his own students, including Wu Yu-hsiang and his brothers, who were officials in the Imperial Qing dynasty bureaucracy.[2] In 1850, Yang was hired by the Imperial family to teach Taijiquan to them and several of their élite Manchu Imperial Guards Brigade units in Beijing's Forbidden City. Among this group was Yang's best known non-family student, Wu Ch'uan-yu.[4] This was the beginning of the spread of Taijiquan from the family art of a small village in central China to an international phenomenon. [5] Due to his influence and the number of teachers he trained, including his own descendants, Yang is directly acknowledged by 4 of the 5 Taijiquan families as having transmitted the art to them.[1][2][5]

The Legend of Yang Wudi

After emerging from Chenjiagou, Yang became famous for never losing a match and never seriously injuring his opponents. Having refined his martial skill to an extremely high level, Yang Lu-ch'an came to be known as Yang Wudi (楊無敵, Yang the Invincible). In time, many legends sprang up around Yang's martial prowess. These legends would serve to inform various biographical books and movies. Though not independently verifiable, several noteworthy episodes are worth mentioning to illustrate the Yang Wudi character:

- The House of Prince Duan, one of the royal families in the capital, employed a large number of boxing masters and wrestlers—some of which were anxious to have a trial of strength with Yang Lu-ch'an. Yang typically declined their challenges. One day, a famous boxing master of high prestige insisted on competing with Yang to see who was the stronger. The boxer suggested that they sit on two chairs and pit their right fists against each other. Yang Luchan had no choice but to agree. Shortly after the contest began, Duan's boxing master started to sweat all over and his chair creaked as if it were going to fall apart; Yang however looked as composed and serene as ever. Finally rising, Yang gently commented to the onlookers: "The Master's skill is indeed superb, only his chair is not as firmly made as mine." The other master was so moved by Yang's modesty that he never failed to praise his exemplary conduct and unmatched martial skill.[6]

- Once while fishing at a lake, two other martial artists hoped to push Yang in the water and ruin his reputation. Yang -— sensing the attacker's intention -— arched his chest, rounded his back, and executed the High Pat on Horse technique. As his back arched and head bowed, the two attackers were bounced into the water simultaneously. He then said to them that he would be easy on them today; but if they were on the ground, he would have punished them more severely. The two attackers quickly swam away.[7]

- In Beijing, a rich man called Chang heard of Yang's great skills and invited him to demonstrate his art. When Yang arrived, Chang thought little of his ability due to his small build—Yang simply did not "look" like a boxer. Yang was served a very simple dinner. Yang Lu-ch'an continued to behave like an honoured guest, despite his host's thoughts. Chang later questioned if Yang's Taijiquan, being so soft, could actually be used to defeat people. Given that he invited Yang on the basis of his reputation as a great fighter, this question was a veiled insult. Yang replied that there were only three kinds of people he could not defeat: men of brass, men of iron and men of wood. Chang invited out his best bodyguard, Liu, to test Yang's skill. Liu entered aggressively and attacked Yang. Yang, employing only a simple yielding technique, threw Liu across the yard. Chang was very impressed and immediately ordered a banquet to be prepared for Yang.[8]

- When Yang was at Guangping, he often fought with people on the castle wall. One opponent was unable to defend against Yang's attacks and kept on retreating to the edge of the wall. Yang's opponent was unable to keep his balance and began to fall over the edge. At the instant before the opponent fell, Yang—from about thirty feet away—leaped forward, caught the opponent's foot and saved him from falling to his death.[9]

Origin of the Moniker Taijiquan

When Yang Lu-ch'an first taught in Yung Nien, his art was referred to as Mien Quan (Cotton Fist) or Hua Quan (Neutralising Fist). Whilst teaching at the Imperial Court, Yang met many challenges, some friendly some not. But he invariably won and in so convincingly using his soft techniques that he gained a great reputation.

Many who frequented the imperial households would come to view his matches. At one such gathering in which Yang had won against several reputable opponents, the scholar Ong Tong He was present. Inspired by the way Yang moved and executed his techniques, Ong felt that Yang's movements and techniques expressed the physical manifestation of the principles of Taiji (太極, the philosophy). Ong wrote for him a matching verse:

| “ | Hands Holding Taiji shakes the whole world, a chest containing ultimate skill defeats a gathering of heroes. | ” |

Thereafter, his art was referred to as Taijiquan and the styles that sprang from his teaching and by association with him was called Taijiquan.[10]

Subsequent lineage

Yang Lu-ch'an passed his art to:

- his second son, but oldest son to live to maturity, Yang Pan-hou (楊班侯, 1837-1890), was also retained as a martial arts instructor by the Chinese Imperial family.[1] Yang Pan-hou became the formal teacher of Wu Ch'uan-yu (Wu Quanyou), a Manchu Banner cavalry officer of the Palace Battalion, even though Yang Lu-ch'an was Wu Ch'uan-yu's first t'ai chi ch'uan teacher.[2] Wu Ch'uan-yu's son, Wu Chien-ch'uan (Wu Jianquan), also a Banner officer, became known as the co-founder (along with his father) of the Wu-style.[5]

- his third son Yang Chien-hou (Jianhou) (1839-1917), who passed it to his sons, Yang Shao-hou (楊少侯, 1862-1930) and Yang Chengfu (楊澄甫, 1883-1936).[1][2][5]

- Wu Yu-hsiang (Wu Yuxiang, 武禹襄, 1813-1880) who also developed his own Wu-style, which eventually, after three generations, led to the development of Sun-style t'ai chi ch'uan.[2][5]

T'ai chi ch'uan lineage tree with Yang-style focus

Note:

- This lineage tree is not comprehensive, but depicts those considered the 'gate-keepers' & most recognised individuals in each generation of Yang-style.

- Although many styles were passed down to respective descendants of the same family, the lineage focused on is that of the Yang style & not necessarily that of the family.

| Key: | NEIJIA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Solid lines | Direct teacher-student. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dot lines | Partial influence /taught informally /limited time. | TAIJIQUAN | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dash lines | Individual(s) omitted. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dash cross | Branch continues. | CHEN-STYLE | Zhaobao-style | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (陈长兴) Chen Changxing 1771–1853 6th gen. Chen Chen Old Frame | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (杨露禅) Yang Luchan 1799–1872 YANG-STYLE Guang Ping Yang Yangjia Michuan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (王蘭亭) Wang Lanting 1840–? 2nd gen. Yang | (杨健侯) Yang Jianhou 1839–1917 2nd gen. Yang 2nd gen. Yangjia Michuan | (杨班侯) Yang Banhou 1837–1892 2nd gen. Yang 2nd gen. Guang Ping Yang Yang Small Frame | (武禹襄) Wu Yuxiang 1812–1880 WU (HAO)-STYLE | Zhaobao He-style | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (李瑞东) Li Ruidong 1851–1917 Li-style | (杨少侯) Yang Shaohou 1862–1930 3rd gen. Yang Yang Small Frame | (吴全佑) Wu Quanyou 1834–1902 1st gen. Wu | (王矯宇) Wang Jaioyu 1836–1939 3rd gen. Guang Ping Yang | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (杨澄甫) Yang Chengfu 1883–1936 3rd gen. Yang Yang Big Frame | (田兆麟) Tian Zhaolin 1891–1960 3rd gen. Yang | Qi Gechen | (吴鉴泉) Wu Jianquan 1870–1942 2nd gen. Wu WU-STYLE 108 Form | Kuo Lien Ying 1895–1984 4th gen. Guang Ping Yang | (孙禄堂) Sun Lutang 1861–1932 SUN-STYLE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (傅仲文) Fu Zhongwen 1903–1994 10th gen. Chen Beijing form | (董英杰) Dong Yingjie 1891–1960 4th gen. Yang | (郑曼青) Zheng Manqing 1902–1975 4th gen. Yang Short (37) Form | (陈微明) Chen Weiming 1881–1958 | (杨振铎) Yang Zhenduo b.1926 4th gen. Yang | (杨振铭) Yang Shouzhong 1910–1985 4th gen. Yang | (張欽霖) Zhang Qinlin 1888–1967 3rd gen. Yangjia Michuan | (田英嘉) Tian Yingjia 1931–2008 4th gen. Yang | Wudang-style | (吴公儀) Wu Gongyi 1900–1970 3rd gen. Wu | (吴公藻) Wu Gongzao 1903–1983 3rd gen. Wu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taiwan | U.S.A | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Robert W. Smith 1926–2011 | (黃性賢) Huang Xingxian 1910–1992 | Benjamin Pang Jeng Lo b.1927 | William C. C. Chen b.1935 | Big Six Tam Gibbs Lou Kleinsmith Ed Young Mort Raphael Maggie Newman Stanley Israel | Little Six Victor Chin Y. Y. Chin Jon Gaines Natasha Gorky Wolfe Lowenthal Ken VanSickle | (杨军) Yang Jun b.1968 5th gen. Yang | Ip Tai Tak 1929–2004 5th gen. Yang | (王延年) Wang Yennien 1914–2008 4th gen. Yangjia Michuan | (田邴原) Tian Bingyuan b.? 5th gen. Yang | Yao Guoqing b.? 5th gen. Yang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CHEN-STYLE | YANG-STYLE | WU-STYLE | WU (HAO)-STYLE | SUN-STYLE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Wile, Douglas (1983). Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions. Sweet Ch'i Press. ISBN 978-0-912059-01-3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Wile, Douglas (1995). Lost T'ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch'ing Dynasty (Chinese Philosophy and Culture). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2654-8.

- ↑ Yang Jun

- ↑ Wu, Kung-tsao (1980, 2006). Wu Family T'ai Chi Ch'uan (吳家太極拳). Chien-ch’uan T’ai-chi Ch’uan Association. ISBN 0-9780499-0-X.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Yip, Y. L. (Autumn 1998). A Perspective on the Development of Taijiquan – Qi, The Journal of Traditional Eastern Health and Fitness Vol. 8 No. 3. Insight Graphics Publishers. ISSN 1056-4004.

- ↑ Gu Liuxin, The Evolution of the Yang School of Taijiquan

- ↑ T.T. Liang

- ↑ http://www.itcca.it/peterlim/histnote.htm

- ↑ http://celestialtaichi.com/content/view/7/49/

- ↑ Peter Lim Tien Tek, The Development Of Yang Style Taijiquan