Ximelagatran

| |

|---|---|

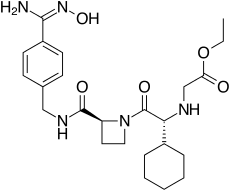

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| ethyl 2-[[(1R)-1-cyclohexyl-2- [(2S)-2-[[4-(N'-hydroxycarbamimidoyl) phenyl]methylcarbamoyl]azetidin-1-yl]- 2-oxo-ethyl]amino]acetate | |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy cat. | uncategorised |

| Legal status | Rx only/POM |

| Routes | Oral |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 20% |

| Metabolism | None |

| Half-life | 3-5h |

| Excretion | Renal (80%) |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 192939-46-1 |

| ATC code | B01AE05 |

| PubChem | CID 9574101 |

| DrugBank | DB04898 |

| ChemSpider | 7848559 |

| UNII | 49HFB70472 |

| KEGG | D01981 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL522038 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C24H35N5O5 |

| Mol. mass | 474 (429 after conversion) |

| SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

Ximelagatran (Exanta or Exarta, H 376/95) is an anticoagulant that has been investigated extensively as a replacement for warfarin[1] that would overcome the problematic dietary, drug interaction, and monitoring issues associated with warfarin therapy. In 2006, its manufacturer AstraZeneca announced that it would withdraw pending applications for marketing approval after reports of hepatotoxicity (liver damage) during trials, and discontinue its distribution in countries where the drug had been approved (Germany, Portugal, Sweden, Finland, Norway, Iceland, Austria, Denmark, France, Switzerland, Argentina and Brazil).[2]

Method of action

Ximelagatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor,[3] was the first member of this class that can be taken orally. It acts solely by inhibiting the actions of thrombin. It is taken orally twice daily, and rapidly absorbed by the small intestine. Ximelagatran is a prodrug, being converted in vivo to the active agent melagatran. This conversion takes place in the liver and many other tissues through dealkylation and dehydroxylation (replacing the ethyl and hydroxyl groups with hydrogen).

Uses

Ximelagatran was expected to replace warfarin and sometimes aspirin and heparin in many therapeutic settings, including deep venous thrombosis, prevention of secondary venous thromboembolism and complications of atrial fibrillation such as stroke. The efficacy of ximelagatran for these indications had been well documented,[4][5][6] except for non valvular atrial fibrillation. The clinical efficacy of ximelagatran in preventing stroke and thrombo-embolic events in atrial fibrilation when compared with warfarin at INR 2–3 was evaluated in one open-label (SPORTIF-III) and one double-blind (SPORTIF-V) prospective randomized trial. The event rates in open label SPORTIF III were 1.64 vs. 2.30%, corresponding to a difference of − 0.66% (95% CI − 1.4, 0.13) and in double-blind SPORTIF V were 1.61 vs. 1.16%, corresponding to a difference of + 0.45% (95% CI = − 0.13, 1.03). These results were not considered to fulfil the current US FDA requirements to prove non-inferiority in efficacy. So ximelagatran was inferior to warfarin in this indication.These findings, in combination with evidence of liver toxicity and higher risk of coronary events, prevented the registration at the first application in the USA in 2004.[7]

An advantage, according to early reports by its manufacturer, was that it could be taken orally without any monitoring of its anticoagulant properties. This would have set it apart from warfarin and heparin, which require monitoring of the international normalized ratio (INR) and the partial thromboplastin time (PTT), respectively. A disadvantage recognised early was the absence of an antidote in case acute bleeding develops, while warfarin can be antagonised by vitamin K and heparin by protamine sulfate.

Side-effects

Ximelagatran was generally well tolerated in the trial populations, but a small proportion (5-6%) developed elevated liver enzyme levels, which prompted the FDA to reject an initial application for approval in 2004. The further development was discontinued in 2006 after it turned out hepatic damage could develop in the period subsequent to withdrawal of the drug. According to AstraZeneca, a chemically different but pharmacologically similar substance, AZD0837, is undergoing testing for similar indications.[2] In a study of deep-vein thrombosis comparing the effectiveness of ximelagatran, with that of a combination of enoxaparin and warfarin, the rate of serious coronary events associated with ximelagatran was 0.81%, versus 0.08% for the latter (P=0.006)[8]

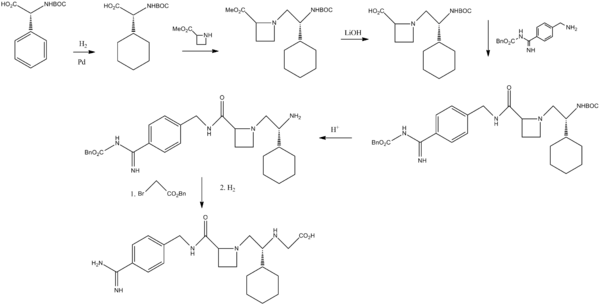

Melagatran synthesis

Sobrera, L. A.; Castaner, J.; Drugs Future, 2002, 27, 201.

References

- ↑ Hirsh J, O'Donnell M, Eikelboom JW (July 2007). "Beyond unfractionated heparin and warfarin: current and future advances". Circulation 116 (5): 552–560. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685974. PMID 17664384.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "AstraZeneca Decides to Withdraw Exanta" (Press release). AstraZeneca. February 14, 2006. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ↑ Ho SJ, Brighton TA (2006). "Ximelagatran: direct thrombin inhibitor". Vasc Health Risk Manag 2 (1): 49–58. doi:10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.1.49. PMC 1993972. PMID 17319469.

- ↑ Eriksson, H; Wahlander K, Gustafsson D, Welin LT, Frison L, Schulman S, THRIVE Investigators (January 2003). "A randomized, controlled, dose-guiding study of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran compared with standard therapy for the treatment of acute deep vein thrombosis: THRIVE I". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 1 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00034.x. PMID 12871538.

- ↑ Francis, CW; Berkowitz SD, Comp PC, Lieberman JR, Ginsberg JS, Paiement G, Peters GR, Roth AW, McElhattan J, Colwell CW Jr; EXULT A Study Group (October 2003). "Comparison of ximelagatran with warfarin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total knee replacement". New England Journal of Medicine 349 (18): 1703–1712. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035162. PMID 14585938.

- ↑ Schulman, S; Wåhlander K, Lundström T, Clason SB, Eriksson H, THRIVE III investigators (October 2003). "Secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism with the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran". New England Journal of Medicine 349 (18): 1713–1721. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa030104. PMID 14585939.

- ↑ Raffaele De Caterina, Steen Husted, Lars Wallentin, Giancarlo Agnelli, Fedor Bachmann, Colin Baigent, Jørgen Jespersen, Steen Dalby Kristensen, Gilles Montalescot, Agneta Siegbahn, Freek W.A. Verheugt and Jeffrey Weitz Anticoagulants in heart disease: current status and perspectives Eur Heart J (2007) 28 (7): 880-913. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl492 http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/28/7/880.full

- ↑ Fiessinger JN, Huisman MV, Davidson BL, et al. Ximelagatran vs low-molecular-weight heparin and warfarin for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis: a randomized trial. JAMA 2005;293:681-689 http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=200334

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||