Wouri estuary

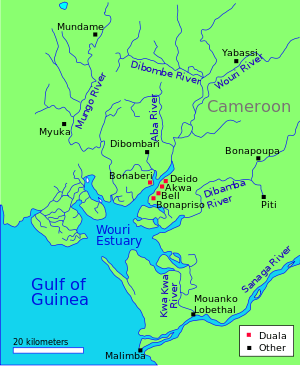

The Wouri estuary, or Cameroon estuary is a large tidal estuary in Cameroon where several rivers come together, emptying into the Bight of Biafra. Douala, the largest city in Cameroon, is at the mouth of the Wouri River where it enters the estuary. The estuary contains extensive mangrove forests, which are being damaged by pollution and population pressures.

Hydrology

The estuary lies to the east of Mount Cameroon and empties into the Bight of Biafra. It is fed by the Mungo, Wouri and Dibamba rivers. The estuary lies in the Douala Basin, a low-lying depression about 30 metres (98 ft) on average about sea level, with many creeks, sand bars and lagoons.[1] The Plio-Pleistocene Wouri alluvial aquifer, a multi-layer system with alternating sequences of marine sands and estuarine mud and silt lies below the estuary and surrounding region and is an important source of well water. The upper aquifer in this system is an unconfined sandy horizon that is hydraulically connected to the brackish waters of the estuary and to the coastal wetlands.[2]

The spring tides at the mouth of the estuary are 2.8 metres (9.2 ft). Rainfall is from 4,000 millimetres (160 in) to 5,000 millimetres (200 in) annually. Salinity is very low, particularly during the rainy season. Surface salinity of 0.4% is common around Douala throughout the year.[3] The Mungo river splits into numerous small channels that empty into the estuary complex.[4] The tidal wave in the bay travels as far as 40 kilometres (25 mi) up the Mungo. In this section of the river, large flats and sand banks are exposed at low tide.[5] The Wouri is affected by the tides for 45 kilometres (28 mi) above Douala, with blocks of tidal forest along its shores throughout this stretch.[3]

To the west of the estuary, the slopes of Mount Cameroon are covered with banana plantations. To the northeast, the mangroves are backed by freshwater tidal swamps 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) wide. One block of freshwater swamp between Muyuka and Dibombari covers 7,500 hectares (19,000 acres).[3] There are still some patches of permanent swamp forest on the Dibamba river, but many others have been cleared and drained for oil palm plantation. The river's fauna are not well protected; particularly endangered is the African Manatee (Trichechus senegalensis).[6]

Fauna and flora

.jpg)

The estuary is a global marine biodiversity hotspot.[7] The mudflats and mangrove forests are home to many waterbirds, and are breeding grounds for fish, shrimp and other wildlife. They can be classified as wetlands of international importance according to criteria under the Ramsar convention.[8] The estuary is home to the Cameroon ghost shrimp, which periodically irrupts into dense swarms. At these times, people catch huge quantities, eating the females or drying them for later use, and making a fish oil from the males.[9][lower-alpha 1]

There are 188,000 hectares (460,000 acres) in total of mangrove forest in the estuary. A large block of mangroves 20 kilometres (12 mi) deep on the north shore extends 35 kilometres (22 mi) up-estuary. The mangrove forest is broken by Bodeaka Bay and Moukouchou Bay, which form wide waterways through the swamp. On the south shore of the estuary, mangroves extend from Douala to Point Soulelaba, the end of the spit that separates the estuary from the sea. These mangroves are divided by the Dibamba River and by Monaka Bay and Island.[3] About 15,000 hectares (37,000 acres) of the mangrove forest is within the Mouanko Reserve, which extends from the south shore of the estuary to the Sanaga River mouth.[6]

The mangrove Rhizophora racemosa, which makes up over 90% of mangroves in Cameroon, reaches a height of 40 metres (130 ft) in the Wouri estuary.[10] Nypa fruticans, an exotic species imported to Nigeria from South-East Asia, has been spreading quickly, encouraged by the local people.[11] The mangrove forests are an important source of wood for making furniture and fences, for smoking fish and for fuel. The leaves of Nypa fruticans are used for thatching house walls and roofs.[12] The mangroves act as a buffer zone, protecting the coast against the worst effects of storms.[7] However, there are no effective controls on mangrove logging, and the Wouri estuary has undergone substantial deforestation.[13]

History

The estuary has traditionally been home to a number of different ethnic groups including the Duala people around the mouth of the Wouri river, the Limba people in the southeast and around the mouth of the Sanaga River, the Mungo people in the north and west of the estuary and the Isubu people in the southwest. These people originally lived through agriculture and fishing.[14] The first Portuguese explorer, Fernando Po, arrived in the estuary in 1472. He was soon followed by traders from Portugal and other European countries.[15] The people of the estuary became trading intermediaries, carrying European goods to the inland regions by canoe and bringing back ivory, slaves and palm products.[14]

Ivory was obtained from the Bamenda Grassfields, to the north.[16] The slave trade began in the 18th century, and was an important economic activity by 1750.[17] Slaves captured in the Chamba wars were brought from the Grassfields via the Mungo River, and slaves from the Nun-Mbam country to the northeast were brought via the Wouri. The Dutch were the main purchasers of slaves in the estuary in the mid-18th century.[18] By the 1830s, the slave trade was in terminal decline due to reduced demand from the United States and punitive action by the British based on the island of Fernando Po.[19] By the mid 19th century, palm oil and palm kernels had become the main trade goods.[20]

The Duala were the leading traders. They prevented European access to the interior and built efficient trade networks.[20] The Duala used marriage ties with the people of the interior to establish trust, with the children of the marriages acting as their agents.[21]

At the request of King Bell and King Akwa of the Duala, the estuary was annexed by Germany in 1884, becoming the nucleus of the colony of Kamerun.[22] The Germans slowly extended their control over the estuary and the vast hinterland of Kamerun over a period of 25 years.[23] At the start of the First World War in 1914, a British expedition from Nigeria won control of the colony. In 1916, Kamerun was divided, with the British taking the lands to the west of the Mungo and the French taking the lands to the east.[23]

In the 1920s, the French improved infrastructure, dredging the estuary to improve access to the port of Douala and rebuilding railways that connected the city to the interior.[24] After the Second World War, the French built a road/rail bridge across the Wouri river, linking Douala and Bonaberi, deepened the shipping canals in the estuary, converted Bonaberi into a banana port and expanded the capacity of Douala port to 900,000 tons, making it the third largest port on the West African coast.[25] The people of the estuary were reunited in 1961 when the modern state of Cameroon was created from the former French Colony and the southern portion of the British colony.

The early settlements of the Duala people at the mouth of the Wouri river - Belltown, Akwatown, Bonapriso, Deido and Bonaberi - have been absorbed by Douala, a city of over three million people that now contains many different ethnic groups, typically each concentrated in their own neighborhoods. Infrastructure such as roads, water supplies, sewage and electricity is poor and in some areas non-existent. Most of the inhabitants work for low wages in informal commercial and industrial enterprises.[26] The port of Douala is limited in its capacity due to its location on the river Wouri, which carries heavy loads of sediment and needs constant dredging.[27] Outside the city, the settlements in the estuary region are villages accessible only by water.

Environmental issues

The ecology of the estuary is under threat from growing pollution from industry, farming and households, threatening both fish yields and human health.[28] Sources of pollution include electroplating and oil refinery industries, pest control in cocoa, coffee and banana plantations, and waste organic oils from land transport, process industries and power generation.[29] The bulk of human-generated sewage is also released into the estuary without treatment. The government infrastructure for controlling pollution is dispersed, weak and ineffective, and there is severe shortage of funding.[30]

Agriculture is the mainstay of the Cameroon economy. Pesticides are not regulated, and also contribute to pollution. Pesticides that have long been banned elsewhere are still in use, or are being held in leaky storage facilities.[30] The growing population is increasing production of export crops such as coffee, cocoa, bananas, palm oil and cotton, using imported pesticides and fertilizers. Typically fertilizers contain urea, ammonia, and phosphorus. Pesticides applied are mostly DDT and other derivatives of organohalogens.[29]

About 95% of Cameroon's industries are based in or around Douala. Their liquid waste is released into the estuary with little or no treatment.[30] Douala's Bassa industrial zone ends in the estuarine creek formation of the Dibamba River, discharging pollutants. The wetlands are quickly being colonized by invasive species, and a great number of phytoplankton have been identified, some of which are caused by the pollution.

The Bonaberi suburb of Douala, with a rapidly growing population of over 500,000, illustrates the urban environmental problems. More than 75% of Bonaberi is 2 metres (6.6 ft) above sea level on average. With limited land, poor people have encroached into wetlands. As of 2002, the dense mangrove swamp forest, which included luxuriant growths of palms, was undergoing extinction due to urbanization. The houses and industrial buildings on the cleared land are poorly built, without adequate drainage. Pools of stagnant water are breeding grounds for disease. Human and industrial waste end up in the channels of the Wouri, reducing its rate of flow. River floods and sea incursions may cause rises of water level from 2 metres (6.6 ft) to 5 metres (16 ft) within a few minutes, destroying buildings and washing raw sewage into the wells. Waterborne diseases such as typhus and dysentery are common causes of death.[31]

Fishery is economically of great importance to Cameroon, with about 40,000 tonnes caught each year, of which one third is exported. In 1994, US$60 million worth of fish was exported to Europe, three quarters of which came from 12 industrial-scale fishing companies.[29] About 40% of the workforce in coastal Cameroon are full-time unregistered fishers.[7] Fish contributes about 44% of the protein in the local population's diet. The mangroves of the estuary are spawning grounds for many types of commercial fish, but they are not protected. The area covered by mangroves continues to shrink and the fish population has been declining steadily. Levels of persistent organic pollutants in the fish are rising.[30]

A 1991 study showed excessive levels of DDTs and PCBs in fish, shrimp and oysters in the area around Douala.[32] High pollution loads of heavy metals such as mercury, lead and cadmium are also a concern.[30]

Oil potential

There appears to be potential for oil and gas production. The Matanda block in the northern half of the estuary and the surrounding region has estimated reserves of between 60 and 300 million barrels. Exploratory work by Gulf Oil several decades ago indicated that production of 4 million barrels a year could be feasible.[33] In April 2008, a subsidiary of Swiss firm Glencore International AG and Afex Global Limited signed a deal with the Cameroon state oil company for a $38 million exploration project in the 1,187 square kilometres (458 sq mi) zone, which was approved by Badel Ndanga Ndinga, Minister of Industries, Mines and Technological Development.[34]

References

- Notes

- Citations

- ↑ Yerima & Van Ranst 2005, pp. 135.

- ↑ Xu & Usher 2006, pp. 48.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Hughes & Hughes 1992, pp. 466.

- ↑ Yerima & Van Ranst 2005, pp. 144.

- ↑ Flemming, Delafontaine & Liebezeit 2000, pp. 225.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cameroon: Ramsar.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Ninan 2009, pp. 374.

- ↑ Napoleon 2007.

- ↑ Holthuis.

- ↑ Spalding, Kainuma & Collins 2010, pp. 243.

- ↑ Saenger 2002, pp. 93.

- ↑ Atheull et al. 2009, pp. 1.

- ↑ Thieme 2005, pp. 228.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Austen & Derrick 1999, pp. 6.

- ↑ Njoh 2003, pp. 75.

- ↑ Behrendt et al. 2010, pp. 93.

- ↑ Vansina 1990, pp. 204.

- ↑ Ogot 1992, pp. 528.

- ↑ Sundiata 1996, pp. 31-32.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Lynn 2002, pp. 63.

- ↑ Lynn 2002, pp. 70.

- ↑ von Joeden-Forgey 2002, pp. 59.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Anyangwe 2009, pp. 4.

- ↑ Thomas 2005, pp. 39.

- ↑ Atangana 2009, pp. 43.

- ↑ Simone 2005, pp. 214ff.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey 2010, pp. 5.12.

- ↑ Gabche & Smith 2007.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Sama 1996.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Munde.

- ↑ McInnes & Jakeways 2002, pp. 143ff.

- ↑ Calamari 1994, pp. 76-77.

- ↑ Hilyard 2008, pp. 214.

- ↑ Glencore - Entrepreneur 2008.

- Sources

- Anyangwe, Carlson (2009). Betrayal of too trusting a people: the UN, the UK and the trust territory of the Southern Cameroons. African Books Collective. ISBN 9956-558-81-8.

- Atangana, Martin-René (2009). French investment in colonial Cameroon: the FIDES era (1946-1957). Peter Lang. ISBN 1-4331-0464-4.

- Atheull, AN; Din, N; Longonje, SN; Koedam, N; Dahdouh-Guebas, F (2009-11-17). "Commercial activities and subsistence utilization of mangrove forests around the Wouri estuary and the Douala-Edea reserve (Cameroon).". Ethnobiol Ethnomed 5: 35. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-5-35. PMC 2785752. PMID 19919680.

- Austen, Ralph A.; Derrick, Jonathan (1999). Middlemen of the Cameroons Rivers: the Duala and their hinterland, c.1600-c.1960. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56664-9.

- Behrendt, Stephen D.; Duke, Antera; Latham, A. J. H.; Northrup, David A. (2010). The diary of Antera Duke, an eighteenth-century African slave trader. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-537618-8.

- "Cameroon". Ramsar Wetlands. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- Flemming, Burghard W.; Delafontaine, Monique T.; Liebezeit, Gerd (2000). Muddy coast dynamics and resource management. Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-50464-8.

- Calamari, D. (1994). Review of pollution in the African aquatic environment. Food & Agriculture Org. ISBN 92-5-103577-6.

- Gabche, C.E.; Smith, V.S. (2007). "Water, Salt and Nutrients Budgets of Two Estuaries in the Coastal Zone of Cameroon". West African Journal of Applied Ecology 3. Retrieved 2011-02-10.

- "Glencore, Afex sign exploration deal with Cameroon". The Entrepreneur. April 11, 2008. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- Hilyard, Joseph, ed. (2008). 2008 International Petroleum Encyclopedia. PennWell Books. ISBN 1-59370-164-0.

- Holthuis, Lipke B.. "Callianassa turnerana". Netherlands Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- Hughes, R. H.; Hughes, J. S. (1992). A directory of African wetlands. IUCN. ISBN 2-88032-949-3.

- Lynn, Martin (2002). Commerce and Economic Change in West Africa: The Palm Oil Trade in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-89326-7.

- McInnes, Robin G.; Jakeways, Jenny (2002). Instability: planning and management : seeking sustainable solutions to ground movement problems. Thomas Telford. ISBN 0-7277-3132-7. Unknown parameter

|c=ignored (help) - Munde, Walters. "Pesticide Use in Cameroon". Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- Napoleon, Chi (September 6, 2007). "Cameroon coastal wetlands of international importance". Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- Ninan, Karachepone Ninan (2009). "Marine and coastal resources in Cameroon: Interplay of climate and climate change". Conserving and valuing ecosystem services and biodiversity: economic, institutional and social challenges. Earthscan. ISBN 1-84407-651-2.

- Njoh, Ambe J. (2003). Planning in contemporary Africa: the state, town planning, and society in Cameroon. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-3346-2.

- Ogot, Bethwell A. (1992). Africa from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 92-3-101711-X.

- Saenger, P. (2002). Mangrove ecology, silviculture, and conservation. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-0686-1.

- Sama, Dudley Achu (17–19 June 1996). "The Constraints in Managing the Pathways of Persistent Organic Pollutants into the Large Marine Ecosystem of the Gulf of Guinea--The Case of Cameroon". Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- Simone, AbdouMaliq (2005). "Local Navigation in Douala". Future city. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28450-3.

- Spalding, Mark; Kainuma, Mami; Collins, Lorna (2010). World Atlas of Mangroves. Earthscan. ISBN 1-84407-657-1.

- Sundiata, I. K. (1996). From slaving to neoslavery: the bight of Biafra and Fernando Po in the era of abolition, 1827-1930. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-14510-7.

- Thieme, Michele L. (2005). Freshwater ecoregions of Africa and Madagascar: a conservation assessment. Island Press. ISBN 1-55963-365-4.

- Thomas, Martin (2005). The French empire between the wars: imperialism, politics and society. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6518-6.

- U.S. Geological Survey (2010). Minerals Yearbook, 2008, V. 3, Area Reports, International, Africa and the Middle East. Government Printing Office. ISBN 1-4113-2965-1.

- Vansina, Jan (1990). Paths in the rainforests: toward a history of political tradition in equatorial Africa. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-12574-2.

- von Joeden-Forgey, Elisa (2002). Mpundu Akwa: the case of the Prince from Cameroon ; the newly discovered speech for the defense by Dr. M. Levi. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 3-8258-7354-4.

- Xu, Yongxin; Usher, Brent (2006). Groundwater pollution in Africa. UNEP/Earthprint. ISBN 0-415-41167-X.

- Yerima, Bernard P.K.; Van Ranst, E. (2005). Major Soil Classification Systems Used in the Tropics:: Soils of Cameroon. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4120-5789-2.

Coordinates: 3°55′05″N 9°33′50″E / 3.918032°N 9.563942°E