Woodrow Wilson

| Woodrow Wilson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 28th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1913 – March 4, 1921 | |

| Vice President | Thomas R. Marshall |

| Preceded by | William Howard Taft |

| Succeeded by | Warren Harding |

| 34th Governor of New Jersey | |

| In office January 17, 1911 – March 1, 1913 | |

| Preceded by | John Fort |

| Succeeded by | James Fielder as Acting Governor |

| 13th President of Princeton University | |

| In office 1902–1910 | |

| Preceded by | Francis Patton |

| Succeeded by | John Stewart (Acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 28, 1856 Staunton, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | February 3, 1924 (aged 67) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Washington National Cathedral Washington, D.C. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Ellen Axson (1885–1914; her death) Edith Bolling (1915–24; his death) |

| Children | Margaret Jessie Eleanor |

| Alma mater | Davidson College Princeton University University of Virginia Johns Hopkins University |

| Profession | Academic Historian Political scientist |

| Religion | Presbyterianism |

| Signature |  |

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856 – February 3, 1924) was the 28th President of the United States, in office from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913. With the Republican Party split in 1912, he led his Democratic Party to control both the White House and Congress for the first time in nearly two decades.[1]

In his first term as President, Wilson persuaded a Democratic Congress to pass a legislative agenda that few presidents have equaled, remaining unmatched up until the New Deal in 1933.[2] This agenda included the Federal Reserve Act, Federal Trade Commission Act, the Clayton Antitrust Act, the Federal Farm Loan Act and an income tax. Child labor was curtailed by the Keating–Owen Act of 1916, but the U.S. Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1918. Wilson also had Congress pass the Adamson Act, which imposed an 8-hour workday for railroads.[3] Although considered a modern liberal visionary giant as President, Wilson was "deeply racist in his thoughts and politics" and his administration racially segregated federal employees and the Navy.[4][5]

Narrowly re-elected in 1916 around the slogan, "He kept us out of war", Wilson's second term was dominated by American entry into World War I. While American non-interventionist sentiment was strong, American neutrality was challenged in early 1917 when the German Empire began unrestricted submarine warfare despite repeated strong warnings and tried to enlist Mexico to attack the U.S. In April 1917, Wilson asked Congress to declare war in order to make "the world safe for democracy." During the war, Wilson focused on diplomacy and financial considerations, leaving the waging of the war itself primarily in the hands of the Army. On the home front in 1917, he began the United States' first draft since the American Civil War; borrowed billions of dollars in war funding through the newly established Federal Reserve Bank and Liberty Bonds; set up the War Industries Board; promoted labor union cooperation; supervised agriculture and food production through the Lever Act; took over control of the railroads; and gave a well-known Flag Day speech that fueled the wave of anti-German sentiment sweeping the country.[6] Wilson also suppressed anti-war movements with the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, a crackdown which broadened and intensified to include real and suspected anarchists and communists during First Red Scare of 1919-1920. After years of opposition, Wilson was pressured to change his position on women's suffrage in 1918, which he advocated as a war measure.[7]

In the late stages of the war, Wilson took personal control of negotiations with Germany, including the armistice. In 1918, he issued his Fourteen Points, his view of a post-war world that could avoid another terrible conflict. In 1919, he went to Paris to add the formation of a League of Nations to the Treaty of Versailles, with special attention on creating new nations out of defunct empires. During an intense fight with Henry Cabot Lodge and the Republican-controlled Senate over giving the League of Nations power to force the U.S. into a war, Wilson suffered a severe stroke that left his wife largely in control of the White House until he left office in March 1921. Despite his poor health, he was able to block any compromises that would enable the Senate to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, and attempted to run for a third term. No leading Democrat wanted Wilson to run again—he was still bedridden, and growing increasingly unpopular amid isolationist backlash against the League and a postwar depression. The Democrats were further weakened in 1920 by the defection of traditional Irish and German Democrats over Wilson's war policies, and the slowness of Wilson to embrace women's suffrage in comparison to Republican candidate Warren G. Harding. With Wilson unpopular, Harding promised a "a return to normalcy" and was elected in an unprecedented popular vote landslide in 1920.[8] Wilson was too ill to leave Washington when his term ended, and he died there in 1924.

An intellectual with a mastery of political language, Wilson was a highly effective partisan campaigner as well as legislative strategist. His biographer Arthur Link says, "He was a virtuoso and a spellbinder during a time when the American people admired oratory above all other political skills. But as a spellbinder he appealed chiefly to men's minds and spirits, and only infrequently to their passions."[9] A Presbyterian of deep religious faith, Wilson appealed to a gospel of service and infused a profound sense of moralism into his idealistic internationalism, now referred to as "Wilsonian". Wilsonianism calls for the United States to enter the world arena to fight for democracy, and has been a contentious position in American foreign policy.[10][11][12] For his sponsorship of the League of Nations, Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize.[13]

Early life

Wilson was born in Staunton, Virginia, on December 28, 1856. His birthplace in Staunton, at 18–24 North Coalter Street, is now the location of the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library. He was the third of four children of Joseph Ruggles Wilson (1822–1903) and Jessie Janet Woodrow (1826–1888).[14] His ancestry was Scottish and Scots-Irish. His paternal grandparents immigrated to the United States from Strabane, County Tyrone, Ireland (now Northern Ireland), in 1807. His mother was born in Carlisle, Cumberland, England, the daughter of Rev. Dr. Thomas Woodrow, born in Paisley, Scotland, and Marion Williamson from Glasgow.[15] His grandparents' whitewashed house has become a tourist attraction in Northern Ireland.[16]

Wilson's father, Joseph Ruggles Wilson, was originally from Steubenville, Ohio, where his grandfather published a newspaper, The Western Herald and Gazette, which was pro-tariff and anti-slavery.[17] Wilson's parents moved south in 1851 and identified with the Confederacy. His father defended slavery, owned slaves and set up a Sunday school for them. They cared for wounded soldiers at their church. The father also briefly served as a chaplain to the Confederate Army.[18] Woodrow Wilson's earliest memory, from the age of three, was of hearing that Abraham Lincoln had been elected and that a war was coming. Wilson would forever recall standing for a moment at Robert E. Lee's side and looking up into his face.[18]

Wilson's father was one of the founders of the Southern Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) after it split from the northern Presbyterians in 1861. Joseph R. Wilson served as the first permanent clerk of the southern church's General Assembly, was Stated Clerk from 1865 to 1898 and was Moderator of the PCUS General Assembly in 1879. Wilson spent the majority of his childhood, up to age 14, in Augusta, Georgia, where his father was minister of the First Presbyterian Church.[19][19]

Wilson was over ten years of age before he learned to read. His difficulty reading may have indicated dyslexia,[20] but as a teenager he taught himself shorthand to compensate.[21] He was able to achieve academically through determination and self-discipline. He studied at home under his father's guidance and took classes in a small school in Augusta.[22] During Reconstruction, Wilson lived in Columbia, South Carolina, the state capital, from 1870 to 1874, where his father was professor at the Columbia Theological Seminary.[23]

Wilson attended Davidson College in North Carolina for the 1873–1874 school year.[24] After medical ailments kept him from returning for a second year, he transferred to Princeton as a freshman when his father took a teaching position at the university. Graduating in 1879, Wilson became a member of Phi Kappa Psi fraternity. Beginning in his second year, he read widely in political philosophy and history. Wilson credited the British parliamentary sketch-writer Henry Lucy as his inspiration to enter public life. He was active in the undergraduate American Whig–Cliosophic Society literary and debating society, serving as speaker of the Whig Party and writing for the Nassau Literary Review,[25] organized a separate Liberal Debating Society,[26] and later coached the Whig–Clio Debate Panel.[27][28]

In 1879, Wilson attended law school at the University of Virginia for one year. Although he never graduated, during his time at the university he was heavily involved in the Virginia Glee Club and the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society, serving as the society's president.[29] His frail health dictated withdrawal, and he went home to Wilmington, North Carolina, where he continued his studies.[30]

In January 1882, Wilson started a law practice in Atlanta. One of his University of Virginia classmates, Edward Ireland Renick, invited him to join his new law practice as partner and Wilson joined him in May 1882. He passed the Georgia Bar. On October 19, 1882, he appeared in court before Judge George Hillyer to take his examination for the bar, which he passed easily. Competition was fierce in a city with 143 other lawyers, and he found few cases to keep him occupied.[31] Nevertheless, he found staying current with the law obstructed his plans to study government to achieve his long-term plans for a political career. In April 1883, Wilson applied to the Johns Hopkins University to study for a doctorate in history and political science and began his studies there in the fall.[31]

Personal life

Wilson's mother was possibly a hypochondriac and Wilson himself seemed to think that he was often in poorer health than he really was. He suffered from hypertension at a relatively early age and may have suffered his first stroke when he was 39.[32]

In 1885, he married Ellen Louise Axson, the daughter of a minister from Savannah, Georgia, during a visit to her relatives in Rome, Georgia. They had three daughters: Margaret Woodrow Wilson (1886–1944); Jessie Wilson (1887–1933); and Eleanor R. Wilson (1889–1967).[33] Ellen Axson Wilson died in 1914, and in 1915 Wilson married Edith Galt, a direct descendant of the Native American woman Pocahontas.[34] Wilson is one of only three presidents to be widowed while in office.[35]

Wilson was an early automobile enthusiast, and he took daily rides while he was President. His favorite car was a 1919 Pierce-Arrow, in which he preferred to ride with the top down.[36] His enjoyment of motoring made him an advocate of funding for public highways.[37]

Wilson was an avid baseball fan. In 1915, he became the first sitting president to attend a World Series game. Wilson had been a center fielder during his Davidson College days. When he transferred to Princeton, he was unable to make the varsity team and so became the team's assistant manager. He was the first President to throw out a first ball at a World Series game.[38]

He cycled regularly, including several cycling vacations in the English Lake District.[39] Unable to cycle around Washington, D.C., as President, Wilson took to playing golf, although he played with more enthusiasm than skill.[40] Wilson holds the record of all the presidents for the most rounds of golf,[40] over 1,000, or almost one every other day. During the winter, the Secret Service would paint golf balls with black paint so Wilson could hit them around in the snow on the White House lawn.[41]

Academic career

Wilson began his graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University in 1883 and three years later completed his doctoral dissertation, "Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics"[42] and received a Ph.D. in history and political science. For his doctorate, Wilson had to learn German.[43]

During the academic year 1886–1887, Wilson was a visiting lecturer at Cornell University, but failed to gain a permanent position. However, he was tapped into the Irving Literary Society by the brothers of his fraternity, Phi Kappa Psi. He joined the faculty of Bryn Mawr College (1885–88) and then Wesleyan University (1888–90),[44] where he also coached the football team and founded the debate team – still called the T. Woodrow Wilson debate team.

In 1890, Wilson joined the Princeton faculty as professor of jurisprudence and political economy. While there, he was one of the faculty members of the short-lived coordinate college, Evelyn College for Women. Additionally, Wilson became the first lecturer of Constitutional Law at New York Law School where he taught with Charles Evans Hughes.[45] Representing the American Whig Society, Wilson delivered an oration at Princeton's sesquicentennial celebration (1896) entitled "Princeton in the Nation's Service". This phrase became the motto of the University, later expanded to "Princeton in the Nation's Service and in the Service of All Nations".[46][47] In this speech, he outlined his vision of the university in a democratic nation, calling on institutions of higher learning "to illuminate duty by every lesson that can be drawn out of the past".[48]

Wilson was annoyed that Princeton was not living up to its potential, complaining "There's a little college down in Kentucky which in 60 years has graduated more men who have acquired prominence and fame than has Princeton in her 150 years."[49]

Writings on government and politics

Government systems

Under the influence of Walter Bagehot's The English Constitution, Wilson saw the United States Constitution as pre-modern, cumbersome, and open to corruption. An admirer of Parliament, Wilson favored a parliamentary system for the United States. Writing in the early 1880s:[50]

I ask you to put this question to yourselves, should we not draw the Executive and Legislature closer together? Should we not, on the one hand, give the individual leaders of opinion in Congress a better chance to have an intimate party in determining who should be president, and the president, on the other hand, a better chance to approve himself a statesman, and his advisers capable men of affairs, in the guidance of Congress

Wilson started Congressional Government, his best-known political work, as an argument for a parliamentary system, but he was impressed by Grover Cleveland, and Congressional Government emerged as a critical description of America's system, with frequent negative comparisons to Westminster. He said, "I am pointing out facts—diagnosing, not prescribing remedies."[51][52]

Wilson believed that America's intricate system of checks and balances was the cause of the problems in American governance. He said that the divided power made it impossible for voters to see who was accountable. If government behaved badly, Wilson asked:[53]

How is the schoolmaster, the nation, to know which boy needs the whipping? ... Power and strict accountability for its use are the essential constituents of good government... It is, therefore, manifestly a radical defect in our federal system that it parcels out power and confuses responsibility as it does. The main purpose of the Convention of 1787 seems to have been to accomplish this grievous mistake. The "literary theory" of checks and balances is simply a consistent account of what our Constitution makers tried to do; and those checks and balances have proved mischievous just to the extent which they have succeeded in establishing themselves.

Wilson singled out the United States House of Representatives for particular criticism:[54]

... divided up, as it were, into forty-seven seignories, in each of which a Standing Committee is the court-baron and its chairman lord-proprietor. These petty barons, some of them not a little powerful, but none of them within reach [of] the full powers of rule, may at will exercise an almost despotic sway within their own shires, and may sometimes threaten to convulse even the realm itself.

Wilson said that the Congressional committee system was fundamentally undemocratic in that committee chairs, who ruled by seniority, determined national policy although they were responsible to no one except their constituents; and that it facilitated corruption.[55]

When William Jennings Bryan captured the Democratic nomination from Cleveland's supporters in 1896, Wilson refused to support the ticket. Instead, he cast his ballot for John M. Palmer, the presidential candidate of the National Democratic Party, or Gold Democrats, a short-lived party that supported a gold standard, low tariffs, and limited government.[56]

In his last scholarly work in 1908, Constitutional Government of the United States, Wilson said that the presidency "will be as big as and as influential as the man who occupies it". By the time of his presidency, Wilson hoped that Presidents could be party leaders in the same way British prime ministers were. Wilson also hoped that the parties could be reorganized along ideological, not geographic, lines. He wrote, "Eight words contain the sum of the present degradation of our political parties: No leaders, no principles; no principles, no parties."[57]

Public administration

Wilson also studied public administration, which he called "government in action; it is the executive, the operative, the most visible side of government, and is of course as old as government itself".[58] He believed that by studying public administration governmental efficiency could be increased.[59]

Wilson was concerned with the implementation of government. He faulted political leaders who focused on philosophical issues and the nature of government and dismissed the critical issues of government administration as mere "practical detail". He thought such attitudes represented the requirements of smaller countries and populations. By his day, he thought, "it is getting to be harder to run a constitution than to frame one."[60] He thought it time "to straighten the paths of government, to make its business less unbusinesslike, to strengthen and purify its organization, and it to crown its dutifulness".[61] He complained that studies of administration drew principally on the history of Continental Europe and an American equivalent was required. He summarized the growth of such foreign states as Prussia, France, and England, highlighting the events that led to advances in administration.

By contrast, he thought the United States required greater compromise because of the diversity of public opinion and the difficulty of forming a majority opinion. Thus practical reform to the government is necessarily slow. Yet Wilson insisted that "administration lies outside the proper sphere of politics"[62] and that "general laws which direct these things to be done are as obviously outside of and above administration."[63] He likens administration to a machine that functions independent of the changing mood of its leaders. Such a line of demarcation is intended to focus responsibility for actions taken on the people or persons in charge. As Wilson put it, "public attention must be easily directed, in each case of good or bad administration, to just the man deserving of praise or blame. There is no danger in power, if only it be not irresponsible. If it be divided, dealt out in share to many, it is obscured..."[64] Essentially, the items under the discretion of administration must be limited in scope, as to not block, nullify, obfuscate, or modify the implementation of governmental decree made by the executive branch.

President of Princeton University

The trustees promoted Professor Wilson to president of Princeton in 1902, replacing Francis Landey Patton, whom the Trustees perceived to be an inefficient administrator. Although the school's endowment was barely $4 million, Wilson sought $2 million for a preceptorial system of teaching, $1 million for a school of science, and nearly $3 million for new buildings and salary increases. As a long-term objective, Wilson sought $3 million for a graduate school and $2.5 million for schools of jurisprudence and electrical engineering, as well as a museum of natural history.[65] He was also able to increase the faculty from 112 to 174, most of whom he selected himself on the basis of their records as outstanding teachers. The curriculum guidelines he developed proved important progressive innovations in the field of higher education.[66] On February 8, 1903, Wilson used a crude racial joke in attacking federal appointments of blacks by President Theodore Roosevelt. Addressing a meeting of Princeton alumni, Wilson joked, in Edmund Morris's telling, that "...this year's groundhog had returned to its burrow [because it] was afraid that Theodore Roosevelt would put a 'coon' in."[67]

To emphasize the development of expertise, Wilson instituted academic departments and a system of core requirements where students met in groups of six with preceptors, followed by two years of concentration in a selected major. He tried to raise admission standards and to replace the "gentleman's C" with serious study. Wilson aspired, as he told alumni, "to transform thoughtless boys performing tasks into thinking men".[68]

In 1906–10, he attempted to curtail the influence of social elites by abolishing the upper-class eating clubs and moving the students into colleges, also known as quadrangles. Wilson's Quad Plan was met with fierce opposition from Princeton's alumni, most importantly Moses Taylor Pyne, the most powerful of Princeton's Trustees. Wilson held his position, saying that giving in "would be to temporize with evil".[69] In October 1907, due to the intensity of alumni opposition, the Board of Trustees withdrew its support for the Quad Plan and instructed Wilson to withdraw it.[70]

Late in his tenure, Wilson confronted Andrew Fleming West, Dean of the graduate school, and West's ally former President Grover Cleveland who was a trustee. Wilson wanted to integrate the proposed graduate building into the same area with the undergraduate colleges. West wanted them to remain separate. When West obtained outside funding, the trustees rejected Wilson's plan for colleges in 1908, and then endorsed West's alternative in 1909. The national press covered the confrontation as a battle of the elites represented by West versus democracy represented by Wilson.[71] It was this confrontation that led to his decision to leave Princeton for politics. He later commented that politics was less brutal than university administration.[72] Wilson was elected president of the American Political Science Association in 1910, but soon decided to leave his Princeton post and enter New Jersey state politics.[73] Wilson left academe with an outstanding reputation as educator and reformer, having set Princeton on the path to becoming one of America's great universities.[74]

Governor of New Jersey

In 1910, Wilson ran for Governor of New Jersey against the Republican candidate Vivian M. Lewis, the State Commissioner of Banking and Insurance. Wilson's campaign focused on his independence from machine politics, and he promised that if elected he would not be beholden to party bosses. Wilson soundly defeated Lewis in the general election by a margin of more than 49,000 votes, although Republican William Howard Taft had carried New Jersey in the 1908 presidential election by more than 80,000 votes.[75] Historian and Teddy Roosevelt biographer Edmund Morris called Wilson in the Governor's race a "dark horse" and attributed his and others' success against the Taft Republicans in 1910 in part to the emergent national progressive message enunciated by Roosevelt in his post-presidency.[76]

In the 1910 election, the Democrats also took control of the General Assembly. The State Senate, however, remained in Republican control by a slim margin. After taking office, Wilson set in place his reformist agenda, ignoring the demands of party machinery. While governor, in a period spanning six months, Wilson established state primaries. This all but took the party bosses out of the presidential election process in the state. He also revamped the public utility commission and introduced worker's compensation.[77]

Election of 1912

Wilson's popularity as governor and his status in the national media gave impetus to his presidential campaign in 1912. He chose Indiana Governor Thomas R. Marshall as his running mate[78] and selected William Frank McCombs, a New York lawyer and a friend from college days, to manage his campaign. Much of Wilson's support came from the South, especially from young progressives in that region, especially intellectuals, editors and lawyers. Wilson managed to maneuver through the complexities of local politics. For example, in Tennessee the Democratic Party was divided on the issue of prohibition. Wilson was progressive and sober, but not dry, and appealed to both sides. They united behind him to win the presidential election in the state, but divided over state politics and lost the gubernatorial election.[79]

The convention deadlocked for more than 40 ballots as no candidate could reach the two-thirds vote required to win the nomination. A leading contender was House Speaker Champ Clark, a prominent progressive strongest in the border states. Other contenders were Governor Judson Harmon of Ohio, and Representative Oscar Underwood of Alabama. They lacked Wilson's charisma and dynamism. Publisher William Randolph Hearst, a leader of the left wing of the party, supported Clark. William Jennings Bryan, the nominee in 1896, 1900 and 1908, played a critical role in opposition to any candidate who had the support of "the financiers of Wall Street". He finally announced for Wilson, who won on the 46th ballot.[80]

In the campaign Wilson promoted the "New Freedom", emphasizing limited federal government and opposition to monopoly powers, often after consultation with his chief advisor Louis D. Brandeis. In the contest for the Republican nomination, President William Howard Taft defeated former president Theodore Roosevelt, who then ran as a Bull Moose Party candidate, which assisted in Wilson's success in the electoral college. Wilson took 41.8% of the popular vote and won 435 electoral votes from 40 states.[81] It is not clear if Roosevelt cost fellow Republican Taft, or fellow progressive Wilson more support.[82]

Presidency, 1913–1921

First term, 1913–1917

Wilson was the first Southerner in the White House since 1869 and worked closely with Southern leaders. Since 1856, he and Grover Cleveland were the only Democrats elected president, so he felt a need to appoint Democrats to all federal positions.[83]

.jpg)

In resolving economic policy issues, he had to manage the conflict between two wings of his party: the agrarian wing led by Bryan and the pro-business wing. With large Democratic majorities in Congress and a healthy economy, he promptly seized the opportunity to implement his agenda.[84] Wilson experienced early success by implementing his "New Freedom" pledges of antitrust modification, tariff revision, and reform in banking and currency matters.[85] He held the first modern presidential press conference, on March 15, 1913, in which reporters were allowed to ask him questions.[86] In 1913, he also became the first president to deliver the State of the Union address in person since 1801 when Thomas Jefferson discontinued this practice.

Wilson's first wife Ellen died on August 6, 1914, casting him into a deep depression. In 1915, he met Edith Galt. They married later that year on December 18.

Federal Reserve 1913

Wilson secured passage of the Federal Reserve Act in late 1913. He had tried to find a middle ground between conservative Republicans, led by Senator Nelson W. Aldrich, and the powerful left wing of the Democratic party, led by William Jennings Bryan, who strenuously denounced private banks and Wall Street. The latter group wanted a government-owned central bank that could print paper money as Congress required. The compromise, based on the Aldrich Plan but sponsored by Democratic Congressmen Carter Glass and Robert Owen, allowed the private banks to control the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, but appeased the agrarians by placing controlling interest in the System in a central board appointed by the president with Senate approval. Moreover, Wilson convinced Bryan's supporters that because Federal Reserve notes were obligations of the government, the plan met their demands for an elastic currency. Having 12 regional banks was meant to weaken the influence of the powerful New York banks, a key demand of Bryan's allies in the South and West. This decentralization was a key factor in winning Glass' support.[87] The final plan passed in December 1913. Some bankers felt it gave too much control to Washington, and some reformers felt it allowed bankers to maintain too much power. Several Congressmen claimed that New York bankers feigned their disapproval.[88]

Wilson named Paul Warburg and other prominent bankers to direct the new system. While power was supposed to be decentralized, the New York branch dominated the Fed as the "first among equals".[89] The new system began operations in 1915 and played a major role in financing the Allied and American war effort.[90] The strengthening of the Federal Reserve was later a major accomplishment of the New Deal.[91]

Economic legislation

The Democrats lowered tariffs with the Underwood Tariff in 1913, though its effects were soon overwhelmed by the changes in trade caused by World War I.[92] Wilson proved especially effective in mobilizing public opinion behind tariff changes by denouncing corporate lobbyists, addressing Congress in person in highly dramatic fashion, and staging an elaborate ceremony when he signed the bill into law.[93] The revenue lost by a lower tariff was replaced by a new federal income tax, authorized by the 16th Amendment. Wilson managed to bring all sides together on the issues of money and banking by the creation in 1913 of the Federal Reserve System, a complex business-government partnership that to this day dominates the financial world.[94] With the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, Wilson helped end the long battles over the trusts.[95]

With the President reaching out to new constituencies, a series of programs were targeted at farmers. The Smith–Lever Act of 1914 created the modern system of agricultural extension agents sponsored by the state agricultural colleges. The agents taught new techniques to farmers. The 1916 Federal Farm Loan Act provided for issuance of low-cost long-term mortgages to farmers.[96]

Child labor was curtailed by the Keating–Owen Act of 1916, but the U.S. Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1918. No major child labor prohibition would take effect until the 1930s.[97]

In the summer of 1916, the railroad brotherhoods threatened to shut down the national transportation system. Wilson tried to bring labor and management together, but when management refused, he had Congress pass the Adamson Act in September 1916, avoiding the strike by imposing an 8-hour workday in the industry (at the same pay as before). Passage of this act helped Wilson gain union support for his reelection; the act was approved by the Supreme Court.[3] Much of this agenda would later serve as an example or a basis of support for the New Deal.[2]

Antitrust

Wilson broke with the big lawsuit tradition of his predecessors Taft and Roosevelt as Trustbusters, finding a new approach to encouraging competition through the Federal Trade Commission, which stopped perceived unfair trade practices. In addition, he pushed through Congress the Clayton Antitrust Act making certain business practices illegal (such as price discrimination, agreements prohibiting retailers from handling other companies' products, and directorates and agreements to control other companies). The power of this legislation was greater than that of previous anti-trust laws because individual officers of corporations could be held responsible if their companies violated the laws. More importantly, the new laws set out clear guidelines that corporations could follow, a dramatic improvement over the previous uncertainties. This law was considered the "Magna Carta" of labor by Samuel Gompers because it ended union liability antitrust laws. In 1916, under threat of a national railroad strike, Wilson approved legislation that increased wages and cut working hours of railroad employees; there was no strike.[98]

War policy – World War I

Wilson spent 1914 through to the beginning of 1917 trying to keep America out of the war in Europe. He offered to be a mediator, but neither the Allies nor the Central Powers took his requests seriously. Republicans, led by Theodore Roosevelt, strongly criticized Wilson's refusal to build up the U.S. Army in anticipation of the threat of war. Wilson won the support of the peace element (especially women and churches) by arguing that an army buildup would provoke war. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, whose pacifist recommendations were ignored by Wilson, resigned in 1915.[99]

On December 18, 1916, Wilson unsuccessfully offered to mediate peace. As a preliminary, he asked both sides to state their minimum terms necessary for future security. The Central Powers replied that victory was certain, and the Allies required the dismemberment of their enemies' empires. No desire for peace or common ground existed, and the offer lapsed.[100]

While German submarines were killing sailors and civilian passengers, Wilson demanded that Germany stop, but he kept the U.S. out of the war. Britain had declared a blockade of Germany to prevent neutral ships from carrying contraband goods to Germany. Wilson protested some British violation of neutral rights, where no one was killed. His protests were mild, and the British knew America would not see it as a casus belli.[99]

Election of 1916

In the 1916 presidential election Colonel House declined any public role, but was Wilson's top campaign advisor. Hodgson says, "he planned its structure; set its tone; guided its finance; chose speakers, tactics, and strategy; and, not least, handled the campaign's greatest asset and greatest potential liability: its brilliant but temperamental candidate."[101]

Renominated without opposition, Wilson used as a major campaign slogan "He kept us out of war", referring to his avoiding open conflict with Germany or Mexico while maintaining a firm national policy. Wilson, however, never promised to keep out of war regardless of provocation. In his acceptance speech on September 2, 1916, Wilson pointedly warned Germany that submarine warfare that took American lives would not be tolerated, saying "The nation that violates these essential rights must expect to be checked and called to account by direct challenge and resistance. It at once makes the quarrel in part our own."[102]

During the 1916 election campaign, while drafting the platform on which he and the Democratic Party would run, Wilson received a suggestion that helped give the document a sharper political focus. Senator Owen of Oklahoma urged Wilson to take ideas from the Progressive Party platform of 1912 “as a means of attaching to our party progressive Republicans who are in sympathy with us in so large a degree.” Wilson liked this suggestion and asked Owen to specify the 1912 Progressive ideas to include. In response, Owen highlighted federal legislation to promote workers’ health and safety, prohibit child labour, provide unemployment compensation, require an eight-hour day and six-day workweek, and establish minimum wages and maximum hours. Wilson, in turn, included in his draft platform a plank that called for all work performed by and for the federal government to provide a minimum wage, an eight-hour day and six-day workweek, health and safety measures, the prohibition of child labour, and (his own additions) safeguards for female workers and a retirement program.[103]

Wilson narrowly won the election, defeating Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes. As governor of New York from 1907 to 1910, Hughes had a progressive record strikingly similar to Wilson's as governor of New Jersey. Theodore Roosevelt would comment that the only thing different between Hughes and Wilson was a shave. However, Hughes had to try to hold together a coalition of conservative Taft supporters and progressive Roosevelt partisans and so his campaign never seemed to take a definite form. Wilson ran on his record and ignored Hughes, reserving his attacks for Roosevelt. When asked why he did not attack Hughes directly, Wilson told a friend to "Never murder a man who is committing suicide."[104]

The result was exceptionally close and the outcome was in doubt for several days. The vote came down to several close states. Wilson won California by 3,773 votes out of almost a million votes cast and New Hampshire by 54 votes. Hughes won Minnesota by 393 votes out of over 358,000. In the final count, Wilson had 277 electoral votes vs. Hughes's 254. Wilson was able to win by picking up many votes that had gone to Teddy Roosevelt or Eugene V. Debs in 1912.[105]

Second term, 1917–1921

Decision for war, 1917

The U.S. had made a declaration of neutrality in 1914. Wilson warned citizens not to take sides in the war for fear of endangering wider U.S. policy. In his address to Congress in 1914, Wilson stated, "Such divisions amongst us would be fatal to our peace of mind and might seriously stand in the way of the proper performance of our duty as the one great nation at peace, the one people holding itself ready to play a part of impartial mediation and speak the counsels of peace and accommodation, not as a partisan, but as a friend."[106]

The U.S. maintained neutrality despite increasing pressure placed on Wilson after the sinking of the British passenger liner RMS Lusitania with arms and American citizens on board. Wilson found it increasingly difficult to maintain U.S. neutrality after Germany, despite its promises in the Arabic pledge and the Sussex pledge, initiated a program of unrestricted submarine warfare early in 1917 that threatened U.S. commercial shipping. Following the revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram, Germany's attempt to enlist Mexico as an ally against the U.S., Wilson took America into World War I to make "the world safe for democracy." The U.S. did not sign a formal alliance with the United Kingdom or France but operated as an "associated" power. The U.S. raised a massive army through conscription and Wilson gave command to General John J. Pershing, allowing Pershing a free hand as to tactics, strategy and even diplomacy.[107]

Wilson had decided by then that the war had become a real threat to humanity. Unless the U.S. threw its weight into the war, as he stated in his declaration of war speech on April 2, 1917,[108] western civilization itself could be destroyed. His statement announcing a "war to end war" meant that he wanted to build a basis for peace that would prevent future catastrophic wars and needless death and destruction. This provided the basis of Wilson's Fourteen Points, which were intended to resolve territorial disputes, ensure free trade and commerce, and establish a peacemaking organization. Included in these fourteen points was the proposal for the League of Nations.[109]

War Message

Woodrow Wilson delivered his War Message to Congress on the evening of April 2, 1917. Introduced to great applause, he remained intense and almost motionless for the entire speech, only raising one arm as his only bodily movement.[110]

Wilson announced that his previous position of "armed neutrality" was no longer tenable now that the Imperial German Government had announced that it would use its submarines to sink any vessel approaching the ports of Great Britain, Ireland or any of the Western Coasts of Europe. He advised Congress to declare that the recent course of action taken by the Imperial German Government constituted an act of war. He proposed that the United States enter the war to "vindicate principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power". He also charged that Germany had "filled our unsuspecting communities and even our offices of government with spies and set criminal intrigues everywhere afoot against our national unity of counsel, our peace within and without our industries and our commerce". Furthermore, the United States had intercepted a telegram sent to the German ambassador in Mexico City that evidenced Germany's attempt to instigate a Mexican attack upon the U.S. The German government, Wilson said, "means to stir up enemies against us at our very doors". He then warned that "if there should be disloyalty, it will be dealt with a firm hand of repression."[111] Wilson closed with the statement that the world must be again safe for democracy.[112]

With 50 Representatives and 6 Senators in opposition, the declaration of war by the United States against Germany was passed by the Congress on April 4, 1917, and was approved by the President on April 6, 1917.

The Fourteen Points

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

|

"Address to the American Indians"

("The great white father now calls you his brothers"), an address given in 1913

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

In a speech to Congress on January 8, 1918, Wilson articulated America's war aims. It was the clearest expression of intention made by any of the belligerent nations. The speech, authored principally by Walter Lippmann, expressed Wilson's progressive domestic policies into comparably idealistic equivalents for the international arena: self-determination, open agreements, international cooperation. Promptly dubbed the Fourteen Points, Wilson attempted to make them the basis for the treaty that would mark the end of the war. They ranged from the most generic principles like the prohibition of secret treaties to such detailed outcomes as the creation of an independent Poland with access to the sea.[113]

Home front

To counter opposition to the war at home, Wilson pushed through Congress the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 to suppress anti-British, pro-German, or anti-war opinions.[111] While he welcomed socialists who supported the war, he pushed at the same time to arrest and deport foreign-born radicals.[114] Citing the Espionage Act, the U.S. Post Office, following the instructions of the Justice Department, refused to carry any written materials that could be deemed critical of the U.S. war effort.[114] Some sixty newspapers judged to have revolutionary or antiwar content were deprived of their second-class mailing rights and effectively banned from the U.S. mails.[114][115] Mere criticism of the Wilson administration and its war policy became grounds for arrest and imprisonment.[114] A Jewish immigrant from Germany, Robert Goldstein, was sentenced to ten years in prison for producing The Spirit of '76, a film that portrayed the British, now an ally, in an unfavorable light.[116]

Wilson's domestic economic policies were strongly pro-labor, but this favorable treatment was extended to only those unions that supported the U.S. war effort, such as the American Federation of Labor (AFL).[116][117] Antiwar groups, anarchists, communists, Industrial Workers of the World members, and other radical labor movements were regularly targeted by agents of the Department of Justice; many of their leaders were arrested on grounds of incitement to violence, espionage, or sedition.[114][118] By 1918, the ranks of those arrested included Eugene Debs, the mild-mannered Socialist Party leader and labor activist, after he gave a speech opposing the war.[114][119] Debs' opposition to the Wilson administration and the war earned the undying enmity of President Wilson, who later called Debs a "traitor to his country".[116] Many recent foreign immigrants, resident aliens who opposed America's participation in World War I, were eventually deported to Soviet Russia or other nations under the sweeping powers granted in the Immigration Act of 1918, which had actually been drafted by Wilson administration officials at the Department of Justice and the Bureau of Immigration.[114][119] Even after the war ended in November 1918, the Wilson administration's attempts to silence radical political opponents continued, culminating in the Palmer Raids, a mass arrest and roundup of some 10,000 anarchists and labor activists, raids led by Wilson's Attorney General, A. Mitchell Palmer.[120] The investigations and prosecutions of antiwar activists by the Department of Justice were heavily criticized by prominent lawyers and law professors of the day, including Felix Frankfurter and Roscoe Pound.[121] The Palmer Raids were eventually stymied in June 1920 by Massachusetts District Court Judge George Anderson, who ordered the discharge of 17 arrested aliens and publicly denounced the Department of Justice's actions.[122][123] He wrote that "a mob is a mob, whether made up of Government officials acting under instructions from the Department of Justice, or of criminals and loafers and the vicious classes."[122][123] Judge Anderson's decision effectively prevented any renewal of the raids.[122][123] Of the 10,000 persons arrested in the Palmer raids, 3,500 were held in detention, of whom 556 were eventually deported to other countries.[124]

In October 1917, President Wilson and Congress created the Office of the Alien Property Custodian; and A. Mitchell Palmer, prior to being appointed Attorney General, was appointed by Wilson to head this agency.[125] On July 15, 1918, President Wilson gave Palmer the power to sell enemy-owned property worth less than $10,000 privately without public auction.[125] Palmer's sale manager, Joseph Guffy, was later indicted on 12 counts for embezzlement of the sale funds, although Guffy was never brought to trial.[125] In the Philippines, transactions of German property sales were rigged for sale to private friends of the local manager. Although Palmer revoked the sales under President Wilson's support, he appointed a new agent who then resold the properties to the original purchasers.[126] In December 1918, Palmer was under suspicion that the sale of Bosch Magneto Company had been rigged, when the firm was sold to Palmer's friend who owned a truck manufacturing business.[127] According to his biographer, Stanley Coben, Palmer lied before the Senate committee about this transaction during his nomination hearings for the appointment of Attorney General.[127] Palmer also was criticized in 1920 for having sold 5,000 German chemical patents too cheaply.[127] Although President Wilson may have been unaware of any illicit transactions, he warned Palmer in a letter, dated September 4, 1918, to use his power sparingly when no other sale was possible.[128]

During the war, Wilson worked closely with Samuel Gompers and the AFL, the railroad brotherhoods, and other 'moderate' unions, which saw enormous growth in membership and wages during Wilson's administration. As there was no rationing, consumer prices soared. As income taxes increased, white-collar workers suffered. Despite this, appeals to buy war bonds were highly successful. The purchase of wartime bonds had the result of shifting the cost of the war to the affluent 1920s.[115]

Wilson set up the first western propaganda office, the United States Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel (thus its popular name, Creel Commission), which filled the country with patriotic anti-German appeals and conducted various forms of censorship.[129] In 1917, Congress authorized ex-President Theodore Roosevelt to raise four divisions of volunteers to fight in France--Roosevelt's World War I volunteers; Wilson refused to accept this offer from his political enemy. Other areas of the war effort were incorporated into the government along with propaganda. The War Industries Board headed by Bernard Baruch set war goals and policies for American factories. Future President Herbert Hoover was appointed to head the Food Administration which encouraged Americans to participate in "Meatless Mondays" and "Wheatless Wednesdays" to conserve food for the troops overseas. The Federal Fuel Administration run by Henry Garfield introduced daylight saving time and rationed fuel supplies such as coal and oil to keep the U.S. military supplied. These and many other boards and administrations were headed by businessmen recruited by Wilson for a-dollar-a-day salary to make the government more efficient in the war effort.[115]

In an effort at reform and to shake up his Mobilization program, Wilson removed the chief of the Army Signal Corps and the chairman of the Aircraft Production Board on April 18, 1918.[130] On May 16, the President launched an investigation, headed by Republican Charles Evans Hughes, into the War Department and the Council of Defense.[131] The Hughes report released on October 31 found no major corruption violations or theft in Wilson's Mobilization program, although the report found incompetence in the aircraft program.[132]

Other foreign affairs

In anticipation of the opening of the Panama Canal, Britain protested that U.S. plans to exempt from tolls all U.S. vessels traveling between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the U.S. in accordance with the Panama Canal Act of 1912, violated the Hay–Pauncefote Treaty. On March 5, 1914, Wilson sent a message to Congress strongly urging the repeal of the exemption. He regarded the exemption as a plain breach of the Treaty and proposed a "voluntary withdrawal from a position everywhere questioned and misunderstood." In spite of strong opposition within his own party, he forced Democrats in Congress to support a repeal of the exemption.[133]

Wilson frequently intervened in Latin American affairs, saying in 1913: "I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men."[134] These interventions included Mexico in 1914, Haiti, Dominican Republic in 1916, Cuba in 1917, and Panama in 1918. The U.S. maintained troops in Nicaragua throughout the Wilson administration and used them to select the president of Nicaragua and then to force Nicaragua to pass the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty. American troops in Haiti, under the command of the federal government, forced the Haitian legislature to choose as Haitian president the candidate Wilson selected. American troops occupied Haiti between 1915 and 1934.[135] Wilson ordered the military occupation of the Dominican Republic shortly after the resignation of its President Juan Isidro Jimenes Pereyra in 1916. The U.S. military worked in concert with wealthy Dominican landowners to suppress the gavilleros, a campesino guerrilla force fighting the occupation. The occupation lasted until 1924, and was notorious for its brutality against those in the resistance.[136] Wilson also negotiated with Colombia a treaty in which the U.S. apologized for its role in the Panama Revolution of 1903–1904.[137]

After Russia left World War I following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the Allies sent troops there to prevent a German or Bolshevik takeover of allied-provided weapons, munitions and other supplies previously shipped as aid to the pre-revolutionary government.[138] Wilson sent armed forces to assist the withdrawal of Czechoslovak Legions along the Trans-Siberian Railway, and to hold key port cities at Arkangel and Vladivostok. Though not sent to engage the Bolsheviks, the U.S. forces engaged in several armed conflicts against forces of the new Russian government. Revolutionaries in Russia resented the American intrusion. As Robert Maddox puts it, "The immediate effect of the intervention was to prolong a bloody civil war, thereby costing thousands of additional lives and wreaking enormous destruction on an already battered society."[139] Wilson withdrew most of the soldiers on April 1, 1920, though some remained until as late as 1922.

In 1919, Wilson guided American foreign policy to "acquiesce" in the Balfour Declaration without supporting Zionism in an official way. Wilson expressed sympathy for the plight of Jews, especially in Poland and in France.[140]

In May 1920, Wilson finally sent a long-deferred proposal to Congress to have the U.S. accept a mandate from the League of Nations to take over Armenia.[141] Bailey notes that the scheme was strongly opposed by American public opinion,[142] while Richard G. Hovannisian states that Wilson "made all the wrong arguments" for the mandate and focused less on the immediate policy than on how history would judge his actions: "[he] wished to place it clearly on the record that the abandonment of Armenia was not his doing."[143] The resolution won the votes of only 23 senators.

Peace Conference 1919

After World War I, Wilson participated in negotiations with the stated aim of assuring statehood for formerly oppressed nations and an equitable peace. On January 8, 1918, Wilson made his famous Fourteen Points address, introducing the idea of a League of Nations, an organization with a stated goal of helping to preserve territorial integrity and political independence among large and small nations alike.[144]

Wilson intended the Fourteen Points as a means toward ending the war and achieving an equitable peace for all the nations. He spent six months in Paris for the Peace Conference (making him the first U.S. president to travel to Europe while in office). He was not well-regarded at the Conference. As John Maynard Keynes observed: "He not only had no proposals in detail, but he was in many respects, perhaps inevitably, ill-informed as to European conditions. And not only was he ill-informed—that was true of Mr. Lloyd George also—but his mind was slow and unadaptable...There can seldom have been a statesman of the first rank more incompetent than the President in the agilities of the council chamber."[145] He worked tirelessly to promote his plan. The charter of the proposed League of Nations was incorporated into the conference's Treaty of Versailles.[146] Japan proposed that the Covenant include a racial equality clause. Wilson was indifferent to the issue, but acceded to strong opposition from Australia and Britain.[147] After the conference, Wilson said that "at last the world knows America as the savior of the world!"[148]

When Wilson traveled to Europe to settle the peace terms, he visited Pope Benedict XV in Rome, making Wilson the first American President to visit the Pope while in office.[149]

For his peace-making efforts, Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize.[13]

Treaty fight, 1919

The next question was whether the United States Senate would approve the treaty by the required two-thirds vote. Public opinion was mixed, with intense opposition from most Republicans, from Germans, and from Irish Catholic Democrats. In numerous meetings with Senators in Washington he discovered the opposition had hardened and the Treaty probably lacked the two-thirds vote needed for passage. Despite his weakened physical condition Wilson decided to barnstorm the Western states, scheduling 29 major speeches and many short ones to rally support.[150]

Wilson had downplayed the theme of Germany as guilty in starting the war in 1917 by calling for "peace without victory", but he took an increasingly hard stand at Paris and rejected advice to soften the Treaty.[151] In his public campaign in summer 1919 to rally American support, he repeatedly stressed Germany's guilt, as in his speech on September 4, 1919, where he said the Treaty:

- "Seeks to punish one of the greatest wrongs ever done in history, the wrong which Germany sought to do to the world and to civilization; and there ought to be no weak purpose with regard to the application of the punishment. She attempted an intolerable thing,and she must be made to pay for the attempt."[152]

Wilson had a series of debilitating strokes and had to cancel his trip on September 26, 1919. He became an invalid in the White House, closely monitored or controlled by his wife, who pretended that all was well and never told Wilson how serious his condition was.[153] Republicans under Senator Lodge controlled both houses of Congress after the 1918 elections. The key point of disagreement was whether the League would diminish the power of Congress to declare war.

The Senate was divided into a crazy quilt of positions on the Versailles question.[154] It proved possible to build a majority coalition, but impossible to build the two-thirds coalition needed to pass a treaty.[155] One block of Democrats strongly supported the Versailles Treaty. A second group of Democrats supported the Treaty but followed Wilson in opposing any amendments or reservations. The largest bloc, led by Senator Lodge, comprised a majority of the Republicans. They wanted a treaty with reservations, especially on Article X, which involved the power of the League of Nations to make war without a vote by the United States Congress. Finally, a bipartisan group of 13 "irreconcilables" opposed a treaty in any form.[156] The closest the Treaty came to passage in mid-November 1919 when Lodge and his Republicans formed a coalition with the pro-Treaty Democrats, and were close to a two-thirds majority for a Treaty with reservations, but Wilson rejected this compromise and enough Democrats followed his lead to end permanently the chances for ratification. Cooper and Bailey suggest that Wilson's stroke on September 25, 1919, had so altered his personality that he was unable to negotiate effectively with Lodge. Cooper says the psychological effects of a stroke were profound: "Wilson's emotions were unbalanced, and his judgment was warped....Worse, his denial of illness and limitations was starting to border on delusion."[157]

During this period, Wilson became less trustful of the press and stopped holding press conferences for them, preferring to use his propaganda unit, the Committee for Public Information, instead.[86] A poll of historians in 2006 cited Wilson's failure to compromise with the Republicans on U.S. entry into the League as one of the 10 largest errors on the part of an American president.[158]

Post war: 1919–1920

Wilson's administration did not plan for the process of demobilization at the war's end. Though some advisers tried to engage the President's attention to what they called "reconstruction", his tepid support for a federal commission evaporated with the election of 1918. Republican gains in the Senate meant that his opposition would have to consent to the appointment of commission members. Instead, Wilson favored the prompt dismantling of wartime boards and regulatory agencies.[159]

Demobilization proved chaotic and violent. Four million soldiers were sent home with little planning, little money, and few benefits. A wartime bubble in prices of farmland burst, leaving many farmers bankrupt or deeply in debt after they purchased new land. Major strikes in the steel, coal, and meatpacking industries followed in 1919.[160] Serious race riots hit Chicago, Omaha, and two dozen other cities.[161]

As the election of 1920 approached, Wilson imagined that a deadlocked Democratic convention might turn to him as the only candidate who would make U.S. participation in the League of Nations the dominant issue. He imagined and sometimes pretended he was healthy enough for the effort, but several times admitted that he knew he could not survive a campaign. No one around the President dared tell him that he was incapable and that the campaign for the League was already lost. At the Convention in late June 1920, some Wilson partisans made efforts on his behalf and sent Wilson hopeful reports, but they were quashed by Wilson's wiser friends.[162]

According to Robert M. Saunders, Wilson began a strategy during the early Twenties for a political comeback. In June 1921, Wilson launched a series of meetings and activities that led to the origins of what became known as “The Document.” The unstated intent of this document, according to Saunders, was to build a platform of principles that would provide the basis for a 1924 return to the White House. Wilson sought to ensure that The Document spoke to concerns over taxes, transportation, and farm problems, and attempted to cast the Democratic Party as the party of the masses, but Wilson either forgot or ignored the social-democratic issues Joseph Patrick Tumulty had advocated in the summer of 1919. According to Saunders, Wilson began to use the term “liberal” in its Twentieth Century context of supporting an activist government, but “he had no intentions of making the Democratic party a vehicle for radical economic or social reform.” For instance, Wilson edited out of The Document points by Louis Brandeis which stressed the need for political and social justice.[163]

Incapacity

The immediate cause of his incapacitation in September 1919 was the physical strain of the public speaking tour he undertook to obtain support for ratification of Treaty of Versailles. In Pueblo, Colorado, on September 25, 1919, he collapsed and never fully recovered.[164]

On October 2, 1919, he suffered a serious stroke that almost totally incapacitated him, leaving him paralyzed on his left side, and only able to see out of a corner of his right eye.[165] He was confined to bed for weeks, sequestered from nearly everyone except his wife and his physician, Dr. Cary Grayson.[166] For at least a few months, he used a wheelchair. Later, he could walk only with the assistance of a cane. His wife and his aide Joe Tumulty helped a journalist, Louis Seibold, present a false account of an interview with the President.[167]

With few exceptions, senior government officials were not allowed to see him for the remainder of his term. His wife took control, selecting issues for his attention and delegating other issues to his cabinet heads. Eventually, Wilson resumed his attendance at cabinet meetings, but his input there was perfunctory at best.[168] By February 1920 the President's true condition was known to all. Nearly every major newspaper expressed qualms about Wilson's fitness for the presidency at a time when the League fight was reaching a climax and domestic issues such as strikes, unemployment, inflation and the threat of Communism were ablaze. There was no mechanism to remove him.[169]

This was the most complex case of presidential disability in American history and became a central argument for the 25th Amendment, which handles the issue of a disabled president.[170][171][172]

Administration and Cabinet

Wilson's chief of staff ("Secretary") was Joseph Patrick Tumulty from 1913 to 1921, but he was largely upstaged after 1916 when Wilson's second wife, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, assumed full control of Wilson's schedule. The most important foreign policy advisor and confidant was "Colonel" Edward M. House until Wilson broke with him in early 1919.[173]

| The Wilson Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Woodrow Wilson | 1913–1921 |

| Vice President | Thomas R. Marshall | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of State | William J. Bryan | 1913–1915 |

| Robert Lansing | 1915–1920 | |

| Bainbridge Colby | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Treasury | William G. McAdoo | 1913–1918 |

| Carter Glass | 1918–1920 | |

| David F. Houston | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of War | Lindley M. Garrison | 1913–1916 |

| Newton D. Baker | 1916–1921 | |

| Attorney General | James C. McReynolds | 1913–1914 |

| Thomas W. Gregory | 1914–1919 | |

| A. Mitchell Palmer | 1919–1921 | |

| Postmaster General | Albert S. Burleson | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Josephus Daniels | 1913–1921 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Franklin K. Lane | 1913–1920 |

| John B. Payne | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | David F. Houston | 1913–1920 |

| Edwin T. Meredith | 1920–1921 | |

| Secretary of Commerce | William C. Redfield | 1913–1919 |

| Joshua W. Alexander | 1919–1921 | |

| Secretary of Labor | William B. Wilson | 1913–1921 |

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

Wilson appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- James Clark McReynolds in 1914. He served more than 26 years and established a consistent record in opposition to Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal programs, including the Tennessee Valley Authority, the National Industrial Recovery Act, and the Social Security Act.

- Louis Dembitz Brandeis in 1916. He served almost 23 years and wrote landmark opinions in cases respecting free speech and the right to privacy.

- John Hessin Clarke in 1916. He served just 6 years on the Court before resigning. He thoroughly disliked his work as an Associate Justice.

Other courts

Along with his Supreme Court appointments, Wilson appointed 75 federal judges, including three Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States, 20 judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 52 judges to the United States district courts.

Retirement, death and personal affairs

In 1921, Wilson and his wife Edith retired from the White House to an elegant 1915 town house in the Embassy Row (Kalorama) section of Washington, D.C.[174] Wilson continued going for daily drives, and attended Keith's vaudeville theatre on Saturday nights. Wilson was one of only two Presidents (Theodore Roosevelt was the first) to have served as president of the American Historical Association.[175]

Wilson attended only two state occasions in his retirement: the ceremonies preceding the burial of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery, in Arlington, Virginia, on Armistice Day (November 11), 1921; and President Warren G. Harding's state funeral in the U.S. Capitol on August 8, 1923. On November 10, 1923, Wilson made a short Armistice Day radio speech from the library of his home, his last national address. The following day, Armistice Day itself, he spoke briefly from the front steps to more than 20,000 well wishers gathered outside the house.[174][176][177]

On February 3, 1924, Wilson died in his S Street home as a result of a stroke and other heart-related problems. He was interred in a sarcophagus in Washington National Cathedral, the only president interred in Washington, D.C.[178]

Mrs. Wilson stayed in the home another 37 years, dying there on December 28, 1961, the day she was to be the guest of honor at the opening of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge across the Potomac River near and in Washington, D.C.[179]

Mrs. Wilson left the home and much of the contents to the National Trust for Historic Preservation to be made into a museum honoring her husband. The Woodrow Wilson House opened to the public in 1963, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.[180]

Wilson wrote his one-page will on May 31, 1917, and appointed his wife Edith as his executrix. He left his daughter Margaret an annuity of $2,500 annually for as long as she remained unmarried, and left to his daughters what had been his first wife's personal property. The rest he left to Edith as a life estate with the provision that at her death, his daughters would divide the estate among themselves. In the event that Edith had a child, her children would inherit on an equal footing with his daughters. As the second Mrs. Wilson had no children from either of her marriages, he was thus providing for the child of a possible subsequent third marriage on her part.[181]

Civil Rights

African Americans

Several historians have described Wilson's policies as racist;[182][183][184] some also describe Wilson personally as a racist.[185][186]

In his book, History of the American People, Wilson depicted white European immigrants with empathy while African American immigrants and their children were regarded as unsuitable for citizenship and unable to assimilate positively into American society.[187] Wilson believed that slavery was wrong on economic labor grounds, rather than for moral reasons.[187] Wilson idealized the slavery system in the South, having viewed masters as patient with "indolent" slaves, whom Wilson believed were like "shiftless children". Wilson held contempt for the belief that African Americans could be free and self-governing.[187] In terms of Reconstruction, Wilson held the common neo-Confederate view that the South was demoralized by Northern carpetbaggers and Congressional imposition of black equality justified extreme measures to reassert white supremacist national and state governments.[188] Wilson viewed blacks as related to the animal world, having illustrated an elderly black man with monkey features.[188] Wilson publicly and privately referred to blacks as "darkies".[188]

In 1912, "an unprecedented number"[184] of African Americans left the Republican Party to cast their vote for Wilson, a Democrat. They were encouraged by his promises of support for minorities. However, once in office, Wilson's cabinet members expanded racially segregationist policies. Black leaders who had supported Wilson in the 1912 election were angered when Wilson placed segregationist white Southerners in charge of many executive departments,[184][189] and the administration acted to reduce the already-meager number of African-Americans in political-appointee positions.[182][189] Wilson's cabinet officials, with the president's blessing, proceeded to establish official segregation in most federal government offices – in some departments for the first time since 1863.[184] New facilities were designed to keep the races working there separated.

Historian Eric Foner says, "[Wilson's] administration imposed full racial segregation in Washington and hounded from office considerable numbers of black federal employees."[182] Segregation was also quickly implemented at the Post Office Department headquarters in Washington, D.C. Many African American employees were downgraded and even fired. The segregation implemented in the Department of the Treasury and the Post Office Department involved not only screened-off working spaces, but also separate lunchrooms and toilets.

Some segregationist federal workplace policies introduced by the Wilson administration would remain until the Truman Administration in the 1940s.[190]

Other steps were taken by the Wilson Administration to make obtaining a civil service job more difficult for blacks. Primary among these was the requirement, implemented in 1914 and continued until 1940, that all candidates for civil service jobs attach a photograph to their application further allowing for discrimination in the hiring process.[191][192]

Despite these policies, Wilson was criticized by such hard-line segregationists as Georgia's Thomas E. Watson, for not going far enough in restricting black employment in the federal government.[193]

Wilson did not interfere with the well-established system of Jim Crow and backed the demands of Southern Democrats that their states be left alone to deal with issues of race and black voting without interference from Washington.[194]

In 1914, Wilson told The New York Times, "If the colored people made a mistake in voting for me, they ought to correct it."[195]

Wilson drafted hundreds of thousands of blacks into the army, giving them equal pay with whites, but kept them in all-black units with white officers, and kept the great majority out of combat.[196] When a delegation of blacks protested the discriminatory actions, Wilson told them "segregation is not a humiliation but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen." W. E. B. Du Bois, a leader of the NAACP who had campaigned for Wilson was in 1918 offered an Army commission in charge of dealing with race relations; DuBois accepted, but he failed his Army physical and did not serve.[197]

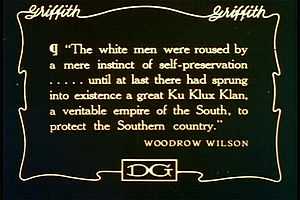

Wilson's segregationist stance as president should perhaps not have come as a surprise; while president of Princeton University, Wilson had discouraged blacks from even applying for admission, preferring to keep the peace among white students than have black students admitted.[198] Wilson's History of the American People (1901) charitably explained the Ku Klux Klan of the late 1860s as the natural outgrowth of Reconstruction, a lawless reaction to a lawless period. Wilson wrote that the Klan "began to attempt by intimidation what they were not allowed to attempt by the ballot or by any ordered course of public action".[199]

White ethnic groups

Wilson had harsh words to say about immigrants in his history books, but after entering politics in 1910, he worked to integrate immigrants into the Democratic party, the army, and American life. During the war, he demanded in return that they repudiate any loyalty to enemy nations. Irish Americans were powerful in the Democratic party and opposed going to war as allies of their traditional enemy Britain, especially after the violent suppression of the Easter Rebellion of 1916. Wilson won them over in 1917 by promising to ask Britain to give Ireland its independence. At Versailles, however, he reneged because he saw the Irish situation purely as an internal UK matter and did not perceive the dispute and the unrest in Ireland as comparable to the plight of the various nationalities in Europe as a fall-out from World War I.[200] As a result, much of the Irish-American community vehemently denounced him. Wilson, in turn, blamed the Irish Americans and German Americans for lack of popular support for the League of Nations, saying:[201]

There is an organized propaganda against the League of Nations and against the treaty proceeding from exactly the same sources that the organized propaganda proceeded from which threatened this country here and there with disloyalty, and I want to say, I cannot say too often, any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready.

Wilson nominated the first Jew to the Supreme Court (Louis Brandeis), starting a long line of Jewish justices who would serve on the nation's highest court.[202]

Legacy

Issue of 1925

On December 28, 1925, less than two years after Wilson's death, the U.S. Post Office issued the 17-cent stamp in his honor. On January 10, 1956, the 7¢ Liberty Issue postage stamp honoring Wilson was also issued. A third 32¢ stamp was issued on February 3, 1998, as part of the Celebrate the Century stamp sheet series.

In recognition of having signed on March 2, 1917 the so-called "Jones Act" that granted United States citizenship to Puerto Ricans, streets in several municipalities in the U.S. territory were renamed "Calle Wilson", including one in the Mariani neighborhood in Ponce and the Condado section of San Juan.

The USS Woodrow Wilson (SSBN-624), a Lafayette-class ballistic missile submarine, was the only ship of the United States Navy to be named for Wilson. She later was converted into an attack submarine and redesignated SSN-624.

The Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs was founded at Princeton in 1930. It was created in the spirit of Wilson's interest in preparing students for leadership in public and international affairs.

Shadow Lawn, the Summer White House for Wilson during his term in office, became part of Monmouth University in 1956. The college has placed a marker on the building, renamed Woodrow Wilson Hall, commemorating the home. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1985.

In 1929, Wilson's image appeared on the $100,000 bill. The bill, now out of print but still legal tender, was used only to transfer money between Federal Reserve banks.[203][204]

In 1944, Darryl F. Zanuck of 20th Century Fox produced a film titled Wilson. It looked back with nostalgia to Wilson's presidency, especially concerning his role as commander-in-chief during World War I.

A section of the Rambla of Montevideo, Uruguay, is named Rambla Presidente Wilson. A street in the 16th arondissement in Paris, running from Trocadéro to the Place de l'Alma, is named the Avenue du Président Wilson. The Pont Wilson crosses the Rhône river in the center of Lyon, France. The Boulevard du Président Wilson extends from the main train station of Strasbourg and connects to the Boulevard Clemenceau. In Bordeaux, the Boulevard du Président Wilson links to the Boulevard George V. The Quai du Président Wilson forms part of the port of Marseille. Praha hlavní nádraží, the main railway station of Prague has, for much of its history, been known as the "Wilson Station" (Czech: Wilsonovo nádraží).

In 2010, Wilson was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame.[205]

In its impact upon American society, while the Wilson Administration accomplished much in the way of social reform during its eight years in office, it did not go as far as Theodore Roosevelt's proposed New Nationalism in relation to the latter's calls for a standard 40-hour work week, minimum wage laws, and a federal system of social insurance. This was arguably a reflection of Wilson's own ideological convictions, who adhered to the classical liberal principles of Jeffersonian Democracy[206] and was opposed to both minimum wage legislation[207] and social insurance, only reluctantly (shortly before his 1916 re-election campaign) consenting to endorse a bill to expand workmen's compensation benefits for Federal employees after there had been widespread public acceptance of the idea.[208] Despite this, Wilson and his New Freedom did much to extend the power of the federal government in social and economic affairs, and arguably paved the way for future reform programs such as the New Deal and the Great Society.

Media

| |

|

|