Wolstenholme's theorem

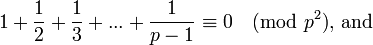

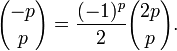

In mathematics, Wolstenholme's theorem states that for a prime number p > 3, the congruence

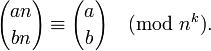

holds, where the parentheses denote a binomial coefficient. For example, with p = 7, this says that 1716 is one more than a multiple of 343. An equivalent formulation is the congruence

The theorem was first proved by Joseph Wolstenholme in 1862. In 1819, Charles Babbage showed the same congruence modulo p2, which holds for all primes p (for p=2 only in the second formulation). The second formulation of Wolstenholme's theorem is due to J. W. L. Glaisher and is inspired by Lucas' theorem.

No known composite numbers satisfy Wolstenholme's theorem and it is conjectured that there are none (see below). A prime that satisfies the congruence modulo p4 is called a Wolstenholme prime (see below).

As Wolstenholme himself established, his theorem can also be expressed as a pair of congruences for (generalized) harmonic numbers:

(Congruences with fractions make sense, provided that the denominators are coprime to the modulus.) For example, with p=7, the first of these says that the numerator of 49/20 is a multiple of 49, while the second says the numerator of 5369/3600 is a multiple of 7.

Wolstenholme primes

A prime p is called a Wolstenholme prime iff the following condition holds:

If p is a Wolstenholme prime, then Glaisher's theorem holds modulo p4. The only known Wolstenholme primes so far are 16843 and 2124679 (sequence A088164 in OEIS); any other Wolstenholme prime must be greater than 109.[1] This result is consistent with the heuristic argument that the residue modulo p4 is a pseudo-random multiple of p3. This heuristic predicts that the number of Wolstenholme primes between K and N is roughly ln ln N − ln ln K. The Wolstenholme condition has been checked up to 109, and the heuristic says that there should be roughly one Wolstenholme prime between 109 and 1024. A similar heuristic predicts that there are no "doubly Wolstenholme" primes, meaning that the congruence holds modulo p5.

A proof of the theorem

There is more than one way to prove Wolstenholme's theorem. Here is a proof that directly establishes Glaisher's version using both combinatorics and algebra.

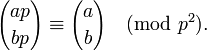

For the moment let p be any prime, and let a and b be any non-negative integers. Then a set A with ap elements can be divided into a rings of length p, and the rings can be rotated separately. Thus, the cyclic group of order pa acts on the set A, and by extension it acts on the set of subsets of size bp. Every orbit of this group action has pk elements, where k is the number of incomplete rings, i.e., if there are k rings that only partly intersect a subset B in the orbit. There are  orbits of size 1 and there are no orbits of size p. Thus we first obtain Babbage's theorem

orbits of size 1 and there are no orbits of size p. Thus we first obtain Babbage's theorem

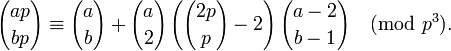

Examining the orbits of size p2, we also obtain

Among other consequences, this equation tells us that the case a=2 and b=1 implies the general case of the second form of Wolstenholme's theorem.

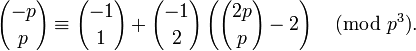

Switching from combinatorics to algebra, both sides of this congruence are polynomials in a for each fixed value of b. The congruence therefore holds when a is any integer, positive or negative, provided that b is a fixed positive integer. In particular, if a=-1 and b=1, the congruence becomes

This congruence becomes an equation for  using the relation

using the relation

When p is odd, the relation is

When p≠3, we can divide both sides by 3 to complete the argument.

A similar derivation modulo p4 establishes that

for all positive a and b if and only if it holds when a=2 and b=1, i.e., if and only if p is a Wolstenholme prime.

The converse as a conjecture

It is conjectured that if

when k=3, then n is prime. The conjecture can be understood by considering k = 1 and 2 as well as 3. When k = 1, Babbage's theorem implies that it holds for n = p2 for p an odd prime, while Wolstenholme's theorem implies that it holds for n = p3 for p > 3. When k = 2, it holds for n = p2 if p is a Wolstenholme prime. Only a few other composite values of n are known when k = 1 (sequence A228562 in OEIS), and none are known when k = 2, much less k = 3. Thus the conjecture is considered likely because Wolstenholme's congruence seems over-constrained and artificial for composite numbers. Moreover, if the congruence does hold for any particular n other than a prime or prime power, and any particular k, it does not imply that

Generalizations

Leudesdorf has proved that for a positive integer n coprime to 6, the following congruence holds:[2]

See also

- Fermat's little theorem

- Wilson's theorem

- Wieferich prime

- Wilson prime

- Wall-Sun-Sun prime

- List of special classes of prime numbers

- Table of congruences

Notes

- ↑ McIntosh, R. J.; Roettger, E. L. (2007), "A search for Fibonacci−Wieferich and Wolstenholme primes", Mathematics of Computation 76 (260): 2087–2094, doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-07-01955-2

- ↑ Leudesdorf, C. (1888). "Some results in the elementary theory of numbers". Proc. London Math. Soc. 20: 199–212. doi:10.1112/plms/s1-20.1.199.

References

- Babbage, C. (1819), "Demonstration of a theorem relating to prime numbers", The Edinburgh philosophical journal 1: 46–49

- Wolstenholme, J. (1862), "On certain properties of prime numbers", The Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 5: 35–39

- Glaisher, J.W.L. (1900), "Congruences relating to the sums of products of the first n numbers and to other sums of products", The Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 31: 1–35

- Glaisher, J.W.L. (1900), "On the residues of the sums of products of the first p−1 numbers, and their powers, to modulus p2 or p3", The Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 31: 321–353

- McIntosh, R. J. (1995), "On the converse of Wolstenholme's theorem", Acta Arithmetica 71 (4): 381–389

- R. Mestrovic, Wolstenholme's theorem: Its Generalizations and Extensions in the last hundred and fifty years (1862—2012).