Wołyń Voivodeship (1921–39)

| Wołyń Voivodeship Województwo wołyńskie | ||

|---|---|---|

| Voivodeship of the Second Polish Republic | ||

| ||

Poland between world wars | ||

| Country | Second Polish Republic | |

| Capital | Łuck | |

| Counties | ||

| Area | ||

| • Total | 35,754 km2 (13,805 sq mi) | |

| Population (1931) | ||

| • Total | 2,085,600 | |

| • Density | 58/km2 (150/sq mi) | |

| ||

Wołyń Voivodeship or Volhynian Voivodeship (Polish: Województwo Wołyńskie, Latin: Palatinatus Volhynensis) was an administrative unit of interwar Poland (1918–1939) with an area of 35,754 km², 11 counties and 22 cities; with Łuck as its capital. The area comprised part of the historical region of Volhynia. In 1945, on the insistence of the Soviet Union (following the Tehran Conference of 1943), Poland's borders were redrawn by the Allies. The Polish population was forcibly resettled westward; and the Voivodeship territory was incorporated by Stalin into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Since 1991 it has been divided between the Rivne and Volyn Oblasts of sovereign Ukraine.

.jpg)

History

The Volhynian voivodeship was created in February 1921 as one of the main administrative divisions of the newly re-established Polish sovereign state after the century of foreign rule. The Second Polish Republic claimed its borders in the aftermath of World War I, as well as, during the subsequent Polish–Soviet War resulting from Semyon Budyonny's military foray into former Russian Poland as far as Warsaw. He withdrew in panic only during the 1920 Polish counteroffensive.[2] It was initially divided to countries of Dubno, Horochow, Kowel, Krzemieniec, Luboml, Łuck, Ostróg, Równe and Włodzimierz Wołyński. In 1 January 1925 gminas of Zdołbunów and Zdołbica of Równe country and gminas of Buderaż and Mizocz of Dubno one were passed to one of Ostróg. Center of Ostróg one was moved to Zdołbunów and was renamed as Zdołbunów one. Also gminas of Bereźne, Derażne, Kostopol, Ludwipol, Stepań and Stydyń were detached from country of Równe and one of Kostopol was formed. At same arrangements Majków gmina of Ostróg was passed to Równe one, Beresteczko gmina of Dubno one was passed to Horochow one, Ołyka gmina of Dubno one was passed to Łuck one, Radziwiłłów gmina of Krzemieniec was passed to Dubno one.[3]

With respect to the Orthodox Ukrainian population in eastern Poland, the Polish government initially issued a decree defending the rights of the Orthodox minorities. In practice, this often failed, as the Catholics, also eager to strengthen their position, had official representation in the Sejm and the courts.[4][5] With time, some 190 Orthodox churches were destroyed (some of them already abandoned)[6] and 150 more were forcibly transformed into Roman Catholic (not Greek Catholic) churches.[7] Such actions were condemned by the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky, who claimed that these acts would "destroy in the souls of our non-united Orthodox brothers the very thought of any possible reunion."[8]

The land reform designed to favour the Poles[9] in mostly Ukrainian populated Volhynia, the agricultural territory where the land question was especially severe, created alienation from the Polish state of even the Orthodox Volhynian population who tended to be much less radical than the Greek Catholic Galicians.[9]

September 1939 and its Aftermath

On 17 September 1939, following German invasion of western Poland and in accordance with the secret protocol of Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Soviet forces proceeded to invade eastern Poland. As the bulk of Polish Army was concentrated in the west fighting Nazi Germany, the Soviets met with limited resistance and their troops quickly moved westward, invading the Voivodeship’s area with considerable ease, until they met with the invading Germans and held the joint victory parade.[10]

In the years of 1942–1944 Volhynia was subject to genocide, conducted by paramilitary groups associated with the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), in particular, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). These forces engaged in summary executions and massacres of the Polish population, along with the destruction of settlements. The razing of towns and villages would continue until August 1944. Władysław and Ewa Siemaszko estimate that around 60,000 Poles were massacred in the province.[11] Ukrainians who opposed the attacks on Poles were themselves targeted with similar aggression.[12]

Geography

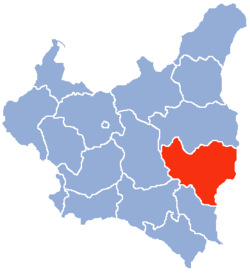

The Wołyń voivodeship was located at the south-eastern corner of Poland, bordering the Soviet Union to the east, the Lublin Voivodeship to the west, the Polesie Voivodeship to the north, and the Lwów and Tarnopol Voivodeships to the south. Initially, the Voivodeship’s area in the new Poland was 30,276 square kilometres. In 16 December 1930, Sarny County, comprising 5,478 km² of land, was transferred from Polesie Voivodeship to the Wołyń Voivodeship.[13] As a result, the total area of the Wołyń Voivodeship increased to 35,754 km², making it Poland's second largest province.

The landscape was flat and hilly for the most part. In the north, there was a flat strip of land called Volhynian Polesie, which extended some 200 kilometres from the Southern Bug river to the Polish-Soviet border. The landscape in the south was more hilly, especially in the extreme south-east corner around the historical town of Krzemieniec, in the Gologory mountains. The province's main rivers were the Styr, the Horyń, and the Słucz.

Demographics

The capital of the Wołyń Voivodeship was Łuck, Volhynia (now: Lutsk, Ukraine). It consisted of 11 powiats (counties), 22 larger towns, 103 villages and literally thousands of smaller communities and khutors (Polish: futory, kolonie), with clusters of farms unable to offer any form of resistance against future military attacks.[14] In 1921 the Wołyń Voivodeship was inhabited by 1,437,569 people and the population density was only 47.5 persons per km2. Around 68% of the population spoke Ukrainian as their first language, 17% - Polish; and 10% Jewish (mainly in towns). There were also German (2.3%) and Czech (1.5%) settlers, who arrived in the 19th century. In 1931, the population grew to 2,085,600 and the density – to 58 persons per km2.

The religion practised in the area was primarily Eastern Orthodox Christian (69.8%). There were also Roman Catholics (15.7%) as well as adherents of Judaism (10%), some Protestants (2.6%) and a few Tatars of the Islamic faith.

Administration

The capital, Łuck, had a population of around 35,600 (as of 1931). Other important centers of the Voivodeship were: Równe (in 1931 pop. 42,000), Kowel (pop. 29,100), Włodzimierz Wołyński (pop. 26,000), Krzemieniec (pop. 22,000), Dubno (pop. 15,300), Ostróg (pop. 13,400) and Zdołbunów (pop. 10,200).

| List of Counties with square area and population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Name | CoA | Area | Population |

| 1 | Kowel county | |

5,682 km² | 255,100 |

| 2 | Sarny county (since 1930) | |

5,478 km² | 181,300 |

| 3 | Łuck county | 4,767 km² | 290,800 | |

| 4 | Kostopol county | |

3,496 km² | 159,600 |

| 5 | Dubno county | |

3,275 km² | 226,700 |

| 6 | Równe county | |

2,898 km² | 252,800 |

| 7 | Krzemieniec county | |

2,790 km² | 243,000 |

| 8 | Włodzimierz Wołyński county | |

2,208 km² | 150,400 |

| 9 | Luboml county | |

2,054 km² | 85,500 |

| 10 | Horochów county | |

1,757 km² | 122,100 |

| 11 | Zdołbunów county | |

1,349 km² | 118,300 |

Industry and infrastructure

The Wołyń Voivodeship was located in the so-called Poland “B”. The bulk of its population, especially the rural areas, was poor. Forest covered 23.7% of the province (as of 1937). Decades of Russian imperial rule had left Volhynia in a state of economic catalepsy, but the agricultural output following the rebirth of Poland quickly grew. The introduction of modern farming practices brought about a dozen-fold increase in wheat production between 1922/23 and 1936/37. By 1937, the voivodeship was home to 760 factories, employing 16,555 workers. Mining, forestry, and food production provided employment for 14,206 individuals. Workers laid-off from industrial plants were also the most likely to start new businesses. In terms of ethnic composition among new business owners, 72,6% were Jewish, 24% Ukrainian, and 23% Polish. The province went through a recession in 1938/39. The tensions between Jewish and Ukrainian shopkeepers increased greatly after the introduction of cooperative stores, which undermined private enterprises, which were mostly Jewish run. Jewish owners were chased out of some 3,000 Ukrainian villages by 1929, with the emerging Ukrainian drive toward economic self-sustainability via cooperatives accompanying their new political aspirations.[15] The situation was much better among the ethnic Czechs and Germans, whose farms were highly efficient.

The railway network was thin, with only a few hubs, the most important at Kowel, with lesser ones at Zdołbunów, Równe and Włodzimierz. The total length of railways within the voivodeship was 1,211 km – just 3.4 km per 100 square kilometres. This was the result of decades of Russian exploitative economics.

Education

Prior to 1917 illiteracy was rife in Volhynia. The Russian Empire maintained only 14 secondary schools in the entire province. Under the restored Polish republic, the number of public schools greatly increased: by 1930, there were already 1,371 schools, growing in numbers to 1,934 by 1938. Illiteracy lingered and according to the 1931 census, as much as 47.8% of the Volhynian population were still illiterate, compared with the national average of 23.1% for the whole of Poland (by early 1939, illiteracy in Volhynia was further reduced to 45%). In order to fight illiteracy, Volhynian authorities organized a network of the so-called moving libraries, which in 1939 consisted of 300 vehicles and 25,000 volumes.

The percentage of pupils in Ukrainian–language–only schools fell from 2.5% in 1929/1930 to 1.2% in 1934/35.[15] Polish government of Ignacy Mościcki, in its 1935 April Constitution of Poland (Chapter 1), redefined the concept of state as home to all faiths and cultures (as opposed to a Polish "nation"), thus reducing the political impact, among others, of Ukrainian nationalism. Senators representing the German and Ukrainian minorities voted in Senat against the new changes, which were nevertheless passed on 16 January 1935.[16]

Voivodes

- Stanisław Jan Krzakowski 14 March 1921 – 7 July 1921

- Tadeusz Łada 7 July 1921 – 12 August 1921 (acting)

- Stanisław Downarowicz 13 August 1921 – 19 August 1921

- Tadeusz Dworakowski 10 October 1921 – 15 March 1922 (acting)

- Mieczysław Mickiewicz 22 February 1922 – 1 February 1923

- Stanisław Srokowski 1 February 1923 – 29 August 1924

- Bolesław Olszewski 29 August 1924 – 4 February 1925

- Aleksander Dębski 4 February 1925 – 28 August 1926

- Władysław Mech 28 August 1926 – 9 July 1928

- Henryk Józewski 9 July 1928 – 29 December 1929

- Józef Śleszyński 13 January 1930 – 5 June 1930 (acting)

- Henryk Józewski 5 June 1930 – 13 April 1938

- Aleksander Hauke-Nowak 13 April 1938 – September 1939

References

- ↑ "Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich". Volume X. Nakład Filipa Sulimierskiego i Władysława Walewskiego, Warsaw. 1880-1914. p. 793. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ↑ Janusz Cisek (2002). "In Defense of the City of the Lion". Kosciuszko, We Are Here!: American Pilots of the Kosciuszko Squadron in Defense of Poland, 1919–1921 (McFarland & Company). pp. 141–152. ISBN 0-7864-1240-2. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ↑ http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU19240680655

- ↑ Paul R. Magocsi, A history of Ukraine,University of Toronto Press, 1996, p.596

- ↑ "Under Tsarist rule the Uniate population had been forcibly converted to Orthodoxy. In 1875, at least 375 Uniate Churches were converted into Orthodox churches. The same was true of many Latin-rite Roman Catholic churches." Orthodox churches were built as symbols of the Russian rule and associated by Poles with Russification during the Partition period

- ↑ The Impact of External Threat on States and Domestic Societie, Manus I. Midlarsky in Dissolving Boundaries, Blackwell Publishers, 2003, ISBN 1-4051-2134-3, Google Print, p.15

- ↑ Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6.

- ↑ Magoscy, R. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Snyder, op cit, Google Print, p.146

- ↑ (Polish) Janusz Magnuski, Maksym Kolomijec, Czerwony Blitzkrieg. Wrzesien 1939: Sowieckie Wojska Pancerne w Polsce (The Red Blitzkrieg. September 1939: Soviet armored troops in Poland). Wydawnictwo Pelta, Warszawa 1994, ISBN 83-85314-03-2, Scan of page 72 of the book.

- ↑ (Polish) Józef Turowski; Władysław Siemaszko, Zbrodnie nacjonalistów ukraińskich dokonane na ludności polskiej na Wołyniu, 1939–1945 (English: Crimes Perpetrated Against the Polish Population of Volhynia by the Ukrainian Nationalists, 1939–1945) Warsaw, Wydawnictwo von borowiecky Publishing, 2000. Second edition, foreword by Prof. Dr Ryszard Szawłowski. ISBN 83-87689-34-3.

- ↑ (Polish) Stanisław Bereś, Rozmowa ze Stanisławem Srokowskim: WIELKA CIEMNOŚĆ SPOWIŁA KRESY Dziennik, Warsaw, 9.01.07, reprinted in Angora Weekly, nr 4/2007, 28.01.07

- ↑ http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/DetailsServlet?id=WDU19300820649

- ↑ Ewa i Władysław Siemaszko, Wołyń w latach okupacji in Ludobójstwo dokonane przez nacjonalistów ukraińskich na ludności polskiej Wołynia 1939 - 1945, ibidem.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 (Polish) Referat na temat: „Województwo wołyńskie w okresie międzywojennym. Gospodarka i społeczeństwo.” (Wołyń Voivodeship in the interwar period. Economy and Society.)

- ↑ Konstytucja kwietniowa 1935 (April Constitution of Poland, 1935). Full text at Wikisource (Polish). See also: Czesław Znamierowski, "Konstytucja styczniowa i ordynacja wyborcza." In: Elita, ustrój, demokracja. Warsaw: Aletheia, 2001. ISBN 83-87045-85-3.

- Maly rocznik statystyczny 1939, Nakladem Glownego Urzedu Statystycznego, Warszawa 1939 (Concise Statistical Year-Book of Poland, Warsaw 1939).

| |||||||||||||