Witzend

For Witzend Productions, see Allan McKeown

| witzend | |

|---|---|

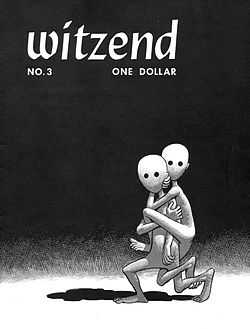

Wally Wood's cover illustration for the third issue of witzend (1967) | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher |

Wally Wood Wonderful Publishing Company |

| Genre |

|

| Publication date | 1966 – 1985 |

| Number of issues | 13 |

| Creative team | |

| Artist(s) | Wally Wood, Al Williamson, Reed Crandall, Steve Ditko, Jack Gaughan, Gil Kane, Jack Kirby, Ralph Reese, Roy G. Krenkel, Angelo Torres, Frank Frazetta, Gray Morrow, Warren Sattler, Bill Elder, Don Martin, Roger Brand, Will Eisner, Richard Bassford, Richard "Grass" Green, Art Spiegelman, Vaughn Bode, Jeff Jones, Bernie Wrightson |

| Creator(s) | Wally Wood |

witzend, published on an irregular schedule spanning decades, was an underground comic showcasing contributions by comic book professionals, leading illustrators and new artists. witzend was launched in 1966 by the writer-artist Wallace Wood, who handed the reins to Bill Pearson (Wonderful Publishing Company) from 1968–1985. The title was printed in lower-case.

Origin

When the illustrator Dan Adkins began working at the Wood Studio in 1965, he showed Wood pages he had been creating for his planned comics-oriented publication, Outlet. This inspired Wood to become an editor-publisher, and he began assembling art and stories for a magazine he titled et cetera. A front cover paste-up with the et cetera logo was prepared and even used in advance solicitation print ads, but when Wood learned of another magazine with a similar title, there was a last-minute title change.[1]

Early issues: Wally Wood editor & publisher

Wood launched witzend in the summer of 1966, with a statement of "no policy" and a desire to give his friends in the comics field a creative detour from the formulaic industry mainstream. During this same period, editor Bill Spicer and critic Richard Kyle began promoting and popularizing the terms "graphic novel" and "graphic story", and in 1967 Spicer changed the title of his Fantasy Illustrated to Graphic Story Magazine. Kyle, Spicer, Wood and Pearson all envisioned an explosion of graphic narratives far afield of the commercial comic book industry.

witzend debuted with Wood's "Animan" and "Bucky Ruckus" while Al Williamson contributed his science fiction adventure, "Savage World." Reed Crandall illustrated Edgar Rice Burroughs, along with a mixed bag of pages by Steve Ditko, Jack Gaughan, Gil Kane, Jack Kirby, Ralph Reese, Roy G. Krenkel and Angelo Torres. The issue wrapped with Frank Frazetta's back cover portrait of Buster Crabbe.

The second issue displayed a front cover by Wood and a back cover by Reese. Gray Morrow's "Orion", which began in this issue of witzend, was completed in Heavy Metal in 1979. Two pages of "Hey, Look!" by Harvey Kurtzman were followed by "a feeble fable" from Warren Sattler, "If You Can't Join 'em... Beat 'em" and more ERB illustrations by Crandall and Frazetta. The center spread presented poems by Wood, Reese and Pearson. Following a Bill Elder cartoon, "Midnight Special" by Ditko and "By the Fountain in the Park" by Don Martin, Wood offered another "Animan" installment.

In the third issue, between a Wood front cover and a Williamson back cover, were Ditko's first "Mr. A" by Ditko, "The Invaders" by Richard Bassford, Wood's "Pipsqueak Papers", more "Hey, Look!" pages and "Last Chance," a previously unpublished 1950s EC New Direction story, drawn by Frazetta and rewritten and edited by Bill Pearson. The issue also featured work by Roger Brand, Will Eisner, Richard "Grass" Green and Art Spiegelman.

With witzend number four, Wood began a serialization of his epic fantasy, "The World of the Wizard King." These installments of illustrated prose fiction were co-authored with Pearson. Shifting from illustrated text to a comics format, Wood continued the storyline in his later graphic novel, published in two editions (one b/w, one color)—The Wizard King (1978) and The King of the World (Les Editions du Triton, 1978).

Later issues: Bill Pearson era

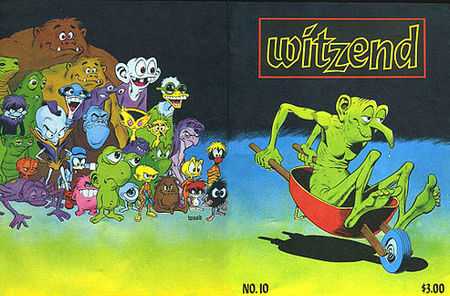

After the fourth issue, Wood sold witzend to Pearson's Wonderful Publishing Company "for the sum of $1.00." Wood remained listed as founder and Editor Emeritus. After editing and publishing #5 (1968) by himself, Pearson co-published the next five issues with various other individuals/entities: #6 with Ed Glaser, #s 7, 8, and 9 with Phil Seuling (founder of the New York Comic Art Convention in 1968), and #10 with the CPL Gang, a group of artists and writers who were publishing other fanzines such as Charlton Bullseye, and CPL (Contemporary Pictorial Literature); from #11 on, Pearson was sole publisher and editor. These post-Wood issues edited by Pearson continued to explore new avenues with contributions from Vaughn Bode, Eisner, Jeff Jones, Wood, Bernie Wrightson, Kenneth Smith, Alex Toth, Roy G. Krenkel, Mike Hinge and many others. Pearson also assembled two theme issues: the final issue #13 (1985) was titled Good Girls - without the witzend logo on the front cover - containing diverse drawings of women, and #9 (1973) was a non-comics issue profiling W.C. Fields, due to then co-publisher Seuling's extreme interest in the actor and his film works. In 1989-90, he also published two digest-sized issues of Witzend Catalog, that were only partly editorial content, including unpublished Krenkel art, the other part being original art pieces for sale.

Reception

A critical survey of the magazine, "Wood at His witzend" by Rick Spanier, appears in Bhob Stewart's biographical anthology, Against the Grain: Mad Artist Wallace Wood (TwoMorrows, 2003). Designer-typographer Spanier once edited a similar graphic story publication, Picture Story Magazine, requested by the Museum of Modern Art for its collection. After analyzing all 13 issues of witzend and fitting it into the context of alternative publishing of the period, Spanier concluded that witzend's "salient point, that comic artists were entitled to more control and ownership of their own work, would eventually be recognized by the publishers of comic books, but it is hard to argue that witzend itself was a key factor in that development. Like so many other visionary endeavors, it may simply have been ahead of its time." [2]

References

Sources

- witzend (Wally Wood) at the Grand Comics Database

- witzend (Wonderful Publishing Company) at the Grand Comics Database

- witzend at the Comic Book DB

External links

| ||||||||||||||