Wind gradient

In common usage, wind gradient, more specifically wind speed gradient[1] or wind velocity gradient,[2] or alternatively shear wind,[3] is the vertical gradient of the mean horizontal wind speed in the lower atmosphere.[4] It is the rate of increase of wind strength with unit increase in height above ground level.[5][6] In metric units, it is often measured in units of meters per second of speed, per kilometer of height (m/s/km), which reduces to the standard unit of shear rate, inverse seconds (s−1).

Simple explanation

Surface friction forces the surface wind to slow and turn near the surface of the Earth, blowing directly towards the low pressure, when compared to the winds in the nearly frictionless flow well above the Earth's surface.[7] This layer, where surface friction slows the wind and changes the wind direction, is known as the planetary boundary layer. Daytime solar heating due to insolation thickens the boundary layer as winds at the surface become increasingly mixed with winds aloft. Radiative cooling overnight decouples the winds at the surface from the winds above the boundary layer, increasing vertical wind shear near the surface, also known as wind gradient.

Background

Typically, due to aerodynamic drag, there is a wind gradient in the wind flow just a few hundred meters above the Earth's surface—the surface layer of the planetary boundary layer. Wind speed increases with increasing height above the ground, starting from zero[6] due to the no-slip condition.[8] Flow near the surface encounters obstacles that reduce the wind speed, and introduce random vertical and horizontal velocity components at right angles to the main direction of flow.[9] This turbulence causes vertical mixing between the air moving horizontally at one level, and the air at those levels immediately above and below it, which is important in dispersion of pollutants[1] and in soil erosion.[10]

The reduction in velocity near the surface is a function of surface roughness, so wind velocity profiles are quite different for different terrain types.[8] Rough, irregular ground, and man-made obstructions on the ground, retard movement of the air near the surface, reducing wind velocity.[4][11] Because of low surface roughness on the relatively smooth water surface, wind speeds do not increase as much with height above sea level as they do on land.[12] Over a city or rough terrain, the wind gradient effect could cause a reduction of 40% to 50% of the geostrophic wind speed aloft; while over open water or ice, the reduction may be only 20% to 30%.[13][14]

For engineering purposes, the wind gradient is modeled as a simple shear exhibiting a vertical velocity profile varying according to a power law with a constant exponential coefficient based on surface type. The height above ground where surface friction has a negligible effect on wind speed is called the "gradient height" and the wind speed above this height is assumed to be a constant called the "gradient wind speed".[11][15][16] For example, typical values for the predicted gradient height are 457 m for large cities, 366 m for suburbs, 274 m for open terrain, and 213 m for open sea.[17]

Although the power law exponent approximation is convenient, it has no theoretical basis.[18] When the temperature profile is adiabatic, the wind speed should vary logarithmically with height,[19] Measurements over open terrain in 1961 showed good agreement with the logarithmic fit up to 100 m or so, with near constant average wind speed up through 1000 m.[20]

The shearing of the wind is usually three-dimensional,[21] that is, there is also a change in direction between the 'free' pressure-driven geostrophic wind and the wind close to the ground.[22] This is related to the Ekman spiral effect. The cross-isobar angle of the diverted ageostrophic flow near the surface ranges from 10° over open water, to 30° over rough hilly terrain, and can increase to 40°-50° over land at night when the wind speed is very low.[14]

After sundown the wind gradient near the surface increases, with the increasing stability.[23] Atmospheric stability occurring at night with radiative cooling tends to contain turbulent eddies vertically, increasing the wind gradient.[10] The magnitude of the wind gradient is largely influenced by the height of the convective boundary layer and this effect is even larger over the sea, where there is no diurnal variation of the height of the boundary layer as there is over land.[24] In the convective boundary layer, strong mixing diminishes vertical wind gradient.[25]

Engineering

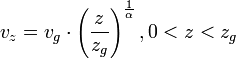

The design of buildings must account for wind loads, and these are affected by wind gradient. The respective gradient levels, usually assumed in the Building Codes, are 500 meters for cities, 400 meters for suburbs, and 300 m for flat open terrain.[26] For engineering purposes, a power law wind speed profile may be defined as follows:[11][15]

where:

= speed of the wind at height

= speed of the wind at height

= gradient wind at gradient height

= gradient wind at gradient height

= exponential coefficient

= exponential coefficient

Wind turbines

Wind turbines are affected by wind gradient. Vertical wind-speed profiles result in different wind speeds at the blades nearest to the ground level compared to those at the top of blade travel, and this in turn affects the turbine operation.[27] The wind gradient can create a large bending moment in the shaft of a two bladed turbine when the blades are vertical.[28] The reduced wind gradient over water means shorter and less expensive wind turbine towers can be used in shallow seas.[12] It would be preferable for wind turbines to be tested in a wind tunnel simulating the wind gradient that they will eventually see, but this is rarely done.[29]

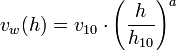

For wind turbine engineering, an exponential variation in wind speed with height can be defined relative to wind measured at a reference height of 10 meters as:[27]

where:

= velocity of the wind at height,

= velocity of the wind at height,  [m/s]

[m/s] = velocity of the wind at height,

= velocity of the wind at height,  = 10 meters [m/s]

= 10 meters [m/s] = Hellman exponent

= Hellman exponent

The Hellman exponent depends upon the coastal location and the shape of the terrain on the ground, and the stability of the air. Examples of values of the Hellman exponent are given in the table below:

| location | α |

|---|---|

| Unstable air above open water surface: | 0.06 |

| Neutral air above open water surface: | 0.10 |

| Unstable air above flat open coast: | 0.11 |

| Neutral air above flat open coast: | 0.16 |

| Stable air above open water surface: | 0.27 |

| Unstable air above human inhabited areas: | 0.27 |

| Neutral air above human inhabited areas: | 0.34 |

| Stable air above flat open coast: | 0.40 |

| Stable air above human inhabited areas: | 0.60 |

Source: "Renewable energy: technology, economics, and environment" by Martin Kaltschmitt, Wolfgang Streicher, Andreas Wiese, (Springer, 2007, ISBN 3-540-70947-9, ISBN 978-3-540-70947-3), page 55

Gliding

In gliding, wind gradient affects the takeoff and landing phases of flight of a glider. Wind gradient can have a noticeable effect on ground launches. If the wind gradient is significant or sudden, or both, and the pilot maintains the same pitch attitude, the indicated airspeed will increase, possibly exceeding the maximum ground launch tow speed. The pilot must adjust the airspeed to deal with the effect of the gradient.[30]

When landing, wind gradient is also a hazard, particularly when the winds are strong.[31] As the glider descends through the wind gradient on final approach to landing, airspeed decreases while sink rate increases, and there is insufficient time to accelerate prior to ground contact. The pilot must anticipate the wind gradient and use a higher approach speed to compensate for it.[32]

Wind gradient is also a hazard for aircraft making steep turns near the ground. It is a particular problem for gliders which have a relatively long wingspan, which exposes them to a greater wind speed difference for a given bank angle. The different airspeed experienced by each wing tip can result in an aerodynamic stall on one wing, causing a loss of control accident.[32][33] The rolling moment generated by the different airflow over each wing can exceed the aileron control authority, causing the glider to continue rolling into a steeper bank angle.[34]

Sailing

In sailing, wind gradient affects sailboats by presenting a different wind speed to the sail at different heights along the mast. The direction also varies with height, but sailors refer to this as "wind shear."[35]

The mast head instruments indication of apparent wind speed and direction is different from what the sailor sees and feels near the surface.[36][37] Sailmakers may introduce sail twist in the design of the sail, where the head of the sail is set at a different angle of attack from the foot of the sail in order to change the lift distribution with height. The effect of wind gradient can be factored into the selection of twist in the sail design, but this can be difficult to predict since the wind gradient may vary widely in different weather conditions.[37] Sailors may also adjust the trim of the sail to account for wind gradient, for example using a boom vang.[37]

According to one source,[38] the wind gradient is not significant for sailboats when the wind is over 6 knots (because a wind speed of 10 knots at the surface corresponds to 15 knots at 300 meters, so the change in speed is negligible over the height of a sailboat's mast). According to the same source, the wind increases steadily with height up to about 10 meters in 5 knot winds but less if there is less wind. That source states that in winds with average speeds of six knots or more, the change of speed with height is confined almost entirely to the one or two meters closest to the surface.[39] This is consistent with another source, which shows that the change in wind speed is very small for heights over 2 meters[40] and with a statement by the Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology[41] according to which differences can be as little as 5% in unstable air.[42]

In kitesurfing, the wind gradient is even more important, because the power kite is flown on 20-30m lines,[43] and the kitesurfer can use the kite to jump off the water, bringing the kite to even greater heights above the sea surface.

Sound propagation

Wind gradient can have a pronounced effect upon sound propagation in the lower atmosphere. This effect is important in understanding sound propagation from distant sources, such as foghorns, thunder, sonic booms, gunshots or other phenomena like mistpouffers. It is also important in studying noise pollution, for example from roadway noise and aircraft noise, and must be considered in the design of noise barriers.[44] When wind speed increases with altitude, wind blowing towards the listener from the source will refract sound waves downwards, resulting in increased noise levels behind the barrier.[45] These effects were first quantified in the field of highway engineering to address variations of noise barrier efficacy in the 1960s.[46]

When the sun warms the Earth's surface, there is a negative temperature gradient in atmosphere. The speed of sound decreases with decreasing temperature, so this also creates a negative sound speed gradient.[47] The sound wave front travels faster near the ground, so the sound is refracted upward, away from listeners on the ground, creating an acoustic shadow at some distance from the source.[48] The radius of curvature of the sound path is inversely proportional to the velocity gradient.[49]

A wind speed gradient of 4 (m/s)/km can produce refraction equal to a typical temperature lapse rate of 7.5 °C/km.[50] Higher values of wind gradient will refract sound downward toward the surface in the downwind direction,[51] eliminating the acoustic shadow on the downwind side. This will increase the audibility of sounds downwind. This downwind refraction effect occurs because there is a wind gradient; the sound is not being carried along by the wind.[52]

There will usually be both a wind gradient and a temperature gradient. In that case, the effects of both might add together or subtract depending on the situation and the location of the observer.[53] The wind gradient and the temperature gradient can also have complex interactions. For example, a foghorn can be audible at a place near the source, and a distant place, but not in a sound shadow between them.[54] In the case of transverse sound propagation, wind gradients do not sensibly modify sound propegation relative to the windless condition; the gradient effect appears to be important only in upwind and downwind configurations.[55]

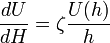

For sound propagation, the exponential variation of wind speed with height can be defined as follows:[45]

where:

= speed of the wind at height

= speed of the wind at height  , and

, and  is a constant

is a constant = exponential coefficient based on ground surface roughness, typically between 0.08 and 0.52

= exponential coefficient based on ground surface roughness, typically between 0.08 and 0.52 = expected wind gradient at height

= expected wind gradient at height

In the 1862 American Civil War Battle of Iuka, an acoustic shadow, believed to have been enhanced by a northeast wind, kept two divisions of Union soldiers out of the battle,[56] because they could not hear the sounds of battle only six miles downwind.[57]

Scientists have understood the effect of wind gradient upon refraction of sound since the mid-1900s; however, with the advent of the U.S. Noise Control Act, the application of this refractive phenomena became applied widely beginning in the early 1970s, chiefly in the application to noise propagation from highways and resultant design of transportation facilities.[58]

Wind gradient soaring

Wind gradient soaring, also called dynamic soaring, is a technique used by soaring birds including albatrosses. If the wind gradient is of sufficient magnitude, a bird can climb into the wind gradient, trading ground speed for height, while maintaining airspeed.[59] By then turning downwind, and diving through the wind gradient, they can also gain energy.[60]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hadlock, Charles (1998). Mathematical Modeling in the Environment. Washington: Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 0-88385-709-X. "Thus we have a “wind-speed gradient” as we move vertically, and this has a tendency to encourage mixing between the air at one level and the air at those levels immediately above and below it."

- ↑ Gorder, P.J.; Kaufman, K.; Greif, R. (1996). "Effect of wind gradient on the trajectory synthesis algorithms of the Center-TRACON Automation System (CTAS)". AIAA, Guidance, Navigation and Control Conference, San Diego, CA. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. "...the effect of a change in mean wind velocity with altitude, the wind velocity gradient..."

- ↑ Sachs, Gottfried (2005-01-10). "Minimum shear wind strength required for dynamic soaring of albatrosses". Ibis (British Ornithologists’ Union) 147 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.2004.00295.x. "...the shear wind gradient is rather weak....the energy gain...is due to a mechanism other than the wind gradient effect."

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Oke, T. (1987). Boundary Layer Climates. London: Methuen. p. 54. ISBN 0-415-04319-0. "Therefore the vertical gradient of mean wind speed (dū/dz) is greatest over smooth terrain, and least over rough surfaces."

- ↑ Crocker, David (2000). Dictionary of Aeronautical English. New York: Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 1-57958-201-X. "wind gradient = rate of increase of wind strength with unit increase in height above ground level;"

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wizelius, Tore (2007). Developing Wind Power Projects. London: Earthscan Publications Ltd. p. 40. ISBN 1-84407-262-2. "The relation between wind speed and height is called the wind profile or wind gradient."

- ↑ "AMS Glossary of Meteorology, Section E". American Meteorological Association. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Brown, G. (2001). Sun, Wind & Light. New York: Wiley. p. 18. ISBN 0-471-34877-5.

- ↑ Dalgliesh, W. A. and D. W. Boyd (1962-04-01). "CBD-28. Wind on Buildings". Canadian Building Digest. "Flow near the surface encounters small obstacles that change the wind speed and introduce random vertical and horizontal velocity components at right angles to the main direction of flow."

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Lal, R. (2005). Encyclopedia of Soil Science. New York: Marcel Dekker. p. 618. ISBN 0-8493-5053-0.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Crawley, Stanley (1993). Steel Buildings. New York: Wiley. p. 272. ISBN 0-471-84298-2.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lubosny, Zbigniew (2003). Wind Turbine Operation in Electric Power Systems: Advanced Modeling. Berlin: Springer. p. 17. ISBN 3-540-40340-X.

- ↑ Harrison, Roy (1999). Understanding Our Environment. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 11. ISBN 0-85404-584-8.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Thompson, Russell (1998). Atmospheric Processes and Systems. New York: Routledge. pp. 102–103. ISBN 0-415-17145-8.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Gupta, Ajaya (1993). Guidelines for Design of Low-Rise Buildings Subjected to Lateral Forces. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 49. ISBN 0-8493-8969-0.

- ↑ Stoltman, Joseph (2005). International Perspectives on Natural Disasters: Occurrence, Mitigation, and Consequences. Berlin: Springer. p. 73. ISBN 1-4020-2850-4.

- ↑ Chen, Wai-Fah (1997). Handbook of Structural Engineering. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 12–50. ISBN 0-8493-2674-5.

- ↑ Ghosal, M. (2005). "7.8.5 Vertical Wind Speed Gradient". Renewable Energy Resources. City: Alpha Science International, Ltd. pp. 378–379. ISBN 978-1-84265-125-4.

- ↑ Stull, Roland (1997). An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 442. ISBN 90-277-2768-6. "...both the wind gradient and the mean wind profile itself can usually be described diagnostically by the log wind profile."

- ↑ Thuillier, R.H.; Lappe, U.O. (1964). "Wind and Temperature Profile Characteristics from Observations on a 1400 ft Tower". Journal of Applied Meteorology (American Meteorological Society) 3 (3): 299–306. Bibcode:1964JApMe...3..299T. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1964)003<0299:WATPCF>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ↑ Mcilveen, J. (1992). Fundamentals of Weather and Climate. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 184. ISBN 0-412-41160-1.

- ↑ Burton, Tony (2001). Wind Energy Handbook. London: J. Wiley. p. 20. ISBN 0-471-48997-2.

- ↑ Köpp, F.; Schwiesow, R.L.; Werner, C. (January 1984). "Remote Measurements of Boundary-Layer Wind Profiles Using a CW Doppler Lidar". Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology (American Meteorological Society) 23 (1): 153. Bibcode:1984JApMe..23..148K. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1984)023<0148:RMOBLW>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ↑ Johansson, C.; Uppsala, S.; Smedman, A.S. (2002). "Does the height of the boundary layer influence the turbulence structure near the surface over the Baltic Sea?". 15th Conference on Boundary Layer and Turbulence. http://ams.confex.com/ams/BLT/techprogram/program_117.htm

|conferenceurl=missing title (help). American Meteorological Society. - ↑ Shao, Yaping (2000). Physics and Modelling of Wind Erosion. City: Kluwer Academic. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7923-6657-7. Unknown parameter

|unused_data=ignored (help) - ↑ Augusti, Giuliano (1984). Probabilistic Methods in Structural Engineering. London: Chapman and Hall. p. 85. ISBN 0-412-22230-2.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Heier, Siegfried (2005). Grid Integration of Wind Energy Conversion Systems. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 45. ISBN 0-470-86899-6.

- ↑ Harrison, Robert (2001). Large Wind Turbines. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 30. ISBN 0-471-49456-9.

- ↑ Barlow, Jewel (1999). Low-Speed Wind Tunnel Testing. New York: Wiley. p. 42. ISBN 0-471-55774-9. "It would be preferable to evaluate windmills in the wind gradient that they will eventually see, but this is rarely done."

- ↑ Glider Flying Handbook. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C.: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration. 2003. pp. 7–16. FAA-8083-13_GFH.

- ↑ Longland, Steven (2001). Gliding. City: Crowood Press, Limited, The. p. 125. ISBN 1-86126-414-3. "The reason for making the increase is because the wind speed increases with height (a `wind gradient')"

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Piggott, Derek (1997). Gliding: a Handbook on Soaring Flight. Knauff & Grove. pp. 85–86, 130–132. ISBN 978-0-9605676-4-5. "The wind gradient is said to be steep or pronounced when the change in wind speed with height is very rapid, and it is in these conditions that extra care must be used when taking off or landing in a glider"

- ↑ Knauff, Thomas (1984). Glider Basics from First Flight to Solo. Thomas Knauff. ISBN 0-9605676-3-1.

- ↑ Conway, Carle (1989). Joy of Soaring. City: Soaring Society of America, Incorporated. ISBN 1-883813-02-6. If the pilot runs into the wind gradient as he is turning into the wind, it is easy to see that there will be less wind across the lower than the higher wing.

- ↑ Jobson, Gary (2004). Gary Jobson's Championship Sailing. City: International Marine/Ragged Mountain Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-07-142381-8. "Wind shear is the difference in direction at varying heights above the water; wind gradient is the difference in wind strength at varying heights above the water."

- ↑ Jobson, Gary (1990). Championship Tactics: How Anyone Can Sail Faster, Smarter, and Win Races. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 323. ISBN 0-312-04278-7. "You'll not recognize wind shear if your apparent wind angle is smaller on one tack than on the other because the apparent wind direction is a combination of boat speed and wind speed - and the sailing speed may be more determined by water conditions in one direction rather than another. This means that the faster a boat goes the more 'ahead' the apparent wind becomes. That is why the 'close reach' direction is the fastest direction of sailing - simply because as the boat speeds up the apparent wind direct goes further and further forward without stalling the sails and the apparent wind speed also increases - so increasing the boat's speed even further. This particular factor is exploited to the full in sand-yachting in which it is common for a sand yacht to exceed the wind speed as measured by a stationary observer. Wind shear is certainly felt because the wind speed at the masthead will be higher than at deck level. Thus gusts of wind can capsize a small sailing boat easily if the crew are not sufficiently wary."

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Garrett, Ross (1996). The Symmetry of Sailing. Dobbs Ferry: Sheridan House. pp. 97–99, 108. ISBN 1-57409-000-3. "Wind speed and direction are normally measured at the top of the mast, and the wind gradient must therefore be known in order to determine the mean wind speed incident on the sail."

- ↑ Bethwaite, Frank (first published in 1993; new edition in 1996, reprinted in 2007). High Performance Sailing. Waterline (1993), Thomas Reed Publications (1996, 1998, and 2001), and Adlard Coles Nautical (2003 and 2007). ISBN 978-0-7136-6704-2. See sections 3.2 and 3.3.

- ↑ See p. 11 of the cited book by Bethwaite

- ↑ http://www.onemetre.net/Design/Gradient/Gradient.htm concerning design of radio-controlled model yachts

- ↑ http://www.bom.gov.au/weather/nsw/amfs/Wind%20Shear.shtml

- ↑ As explained in Bethwaite's book, the air is turbulent near the surface if the wind speed is greater than 6 knots

- ↑ Currer, Ian (2002). Kitesurfing. City: Lakes Paragliding. p. 27. ISBN 0-9542896-0-9.

- ↑ Foss, Rene N. (June 1978). Ground Plane Wind Shear Interaction on Acoustic Transmission. WA-RD 033.1. Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Bies, David (2003). Engineering Noise Control; Theory and Practice. London: Spon Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-415-26713-7. "As wind speed generally increases with altitude, wind blowing towards the listener from the source will refract sound waves downwards, resulting in increased noise levels."

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan, Analysis of Highway Noise, Journal of Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, Vol. 2, No. 3, Biomedical and Life Sciences and Earth and Environmental Science Issue, Pages 387-392, September 1973, Springer Verlag, Netherlands ISSN 0049-6979

- ↑ Ahnert, Wolfgang (1999). Sound Reinforcement Engineering. Taylor & Francis. p. 40. ISBN 0-419-21810-6.

- ↑ Everest, F. (2001). The Master Handbook of Acoustics. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 262–263. ISBN 0-07-136097-2.

- ↑ Lamancusa, J. S. (2000). "10. Outdoor sound propagation" (pdf). Noise Control. ME 458: Engineering Noise Control. State College, PA: Penn State University. pp. 10.6–10.7.

- ↑ Uman, Martin (1984). Lightning. New York: Dover Publications. p. 196. ISBN 0-486-64575-4.

- ↑ Volland, Hans (1995). Handbook of Atmospheric Electrodynamics. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-8493-8647-0.

- ↑ Singal, S. (2005). Noise Pollution and Control Strategy. Alpha Science International, Ltd. p. 7. ISBN 1-84265-237-0. "It may be seen that refraction effects occur only because there is a wind gradient and it is not due to the result of sound being convected along by the wind."

- ↑ N01-N07 Sound Ranging. Basic Science & Technology Section. Royal School Of Artillery. 2002-12-19. pp. N–12. "...there will usually be both a wind gradient and a temperature gradient."

- ↑ Mallock, A. (1914-11-02). "Fog Signals: Areas of Silence and Greatest Range of Sound". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character 91 (623): 71–75. Bibcode:1914RSPSA..91...71M. doi:10.1098/rspa.1914.0103.

- ↑ Malbequi, P.; Delrieux, Y.; Canard-caruana, S. (1993). "Wind tunnel study of 3D sound propagation in presence of a hill and of a wind gradient". ONERA, TP no 111: 5. Bibcode:1993ONERA....R....M.

- ↑ Cornwall, Sir (1996). Grant as Military Commander. Barnes & Noble Inc. ISBN 1-56619-913-1 pages = p. 92 Check

|isbn=value (help). - ↑ Cozzens, Peter (2006). The Darkest Days of the War: the Battles of Iuka and Corinth. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-5783-1.

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael and Gary L. Latshaw, "The Relationship between Highway Planning and Urban Noise", Proceedings of the ASCE, Urban Transportation Division specialty conference, May 21/23, 1973, Chicago, Ill., American Society of Civil Engineers

- ↑ Alexander, R. (2002). Principles of Animal Locomotion. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 206. ISBN 0-691-08678-8.

- ↑ Alerstam, Thomas (1990). Bird Migration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 275. ISBN 0-521-44822-0.