Simon Winchester

| Simon Winchester | |

|---|---|

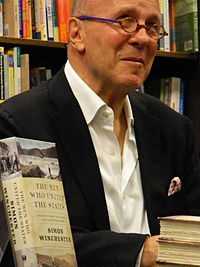

Winchester in New York City for discussion and book signing, 2013 | |

| Born |

28 September 1944 London, England |

| Education | University of Oxford, M.A. Geology, 1966 |

| Occupation | Journalist, author |

| Employer | The Guardian |

| Spouse(s) | Setsuko Sato |

| Website | |

| simonwinchester.com | |

Simon Winchester, OBE (born 28 September 1944), is a British-born American author and journalist who resides in the United States. Through his career at The Guardian, Winchester covered numerous significant events, including Bloody Sunday and the Watergate Scandal. As an author, Winchester has written or contributed to more than a dozen nonfiction books, has written one novel, and his articles have appeared in several travel publications, including Condé Nast Traveler, Smithsonian Magazine, and National Geographic.

Early life and education

Born in London, Winchester attended several boarding schools in Dorset.[1] He spent a year hitchhiking around the United States,[2] then in 1963 went up to St Catherine's College, Oxford to study geology. He graduated in 1966 with a degree in geology and found work with Falconbridge of Africa, a Canadian mining company. His first assignment was to work as a field geologist searching for copper deposits in Uganda.[3]

Career

While on assignment in Uganda, Winchester happened upon a copy of James Morris' Coronation Everest – an account of the 1953 expedition that led to the first successful expedition to reach the summit of Mount Everest.[4] Reading the book instilled in Winchester the desire to be a writer, so he sought career advice from Morris by mail. Morris urged Winchester to give up geology the very day he received the letter, and get a job as a writer on a newspaper.[5]

In 1969, Winchester joined The Guardian, first as regional correspondent based in Newcastle upon Tyne, but later as their Northern Ireland Correspondent.[1] Winchester's time in Northern Ireland placed him around several events of The Troubles, including the events of Bloody Sunday and the Belfast Hour of Terror.[6][7] In 1971, Winchester became part of the controversy over British press coverage of Northern Ireland when he was denounced on the floor of Parliament by Bernadette Devlin for his part in justifying the shooting death of Berney Watt by British soldiers.[8]

After leaving Northern Ireland in 1972, Winchester was briefly assigned to Calcutta before becoming The Guardian's American correspondent in Washington, D.C., where he covered news ranging from the end of Richard Nixon's administration[9] to the start of Jimmy Carter's presidency.[3] In 1982, while working as the Chief Foreign Feature Writer for The Sunday Times, Winchester was on location for the invasion of the Falklands Islands by Argentine forces. Suspected of being a spy, Winchester was held as a prisoner in Tierra del Fuego for three months.[10] In the BBC television drama about the invasion, An Ungentlemanly Act, Winchester was played by Paul Geoffrey.

In 1985, Winchester shifted to work as a freelance writer and travelled to Hong Kong.[1] When Condé Nast re-branded Signature magazine as Condé Nast Traveler, Winchester was appointed the Asia-Pacific Editor.[11] Over the next decade and a half, Winchester contributed to a number of travel publications including the aforementioned Traveler, as well as National Geographic and Smithsonian magazine.[10]

Winchester's first book, In Holy Terror, was published by Faber and Faber in 1975. The book drew heavily on his first-hand experiences during the turmoils in Ulster. In 1976, Winchester published his second book, American Heartbeat, which dealt with his personal travels through the American heartland. Winchester's third book, Prison Diary, was a recounting of his imprisonment in Tierra del Fuego during the Falklands War and, as noted by Dr. Jules Smith, is responsible for his rise to prominence in the United Kingdom.[10]

Winchester's first truly successful book was The Professor and the Madman (1998) published by Penguin UK as The Surgeon of Crowthorne. Telling the story of the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary, the book was a New York Times Best Seller,[12] and the rights to a film version were optioned by Mel Gibson;[13] likely to be directed by John Boorman.[14]

Though he still writes travel books, Winchester has repeated the narrative non-fiction form he used in The Professor and the Madman several times, resulting in multiple best-selling books. His 2001 book, The Map that Changed the World focused on geologist William Smith and was his second New York Times best seller.[15] The year 2003 saw the release of another Winchester book on the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary, The Meaning of Everything, as well as the best-selling Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded.[16] Winchester followed Krakatoa's volcano with San Francisco's 1906 earthquake in A Crack in the Edge of the World.[17] The Man Who Loved China (2008) retells the life of eccentric Cambridge scholar Joseph Needham who helped to expose China to the western world.[18]The Alice Behind Wonderland, an exploration of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson's (Lewis Carroll) work in photography and his relationship with Alice Liddell, was released 11 March 2011.[19]

On 4 July 2011, Winchester was naturalized as an American citizen in a ceremony aboard the USS Constitution.[2]

Simon Winchester's latest book, The Men Who United the States: America's Explorers, Inventors, Eccentrics and Mavericks, and the Creation of One Nation, Indivisible was released on 15 October 2013.

Bibliography

- 1975 – In Holy Terror

- 1976 – American Heartbeat

- 1983 – Stones of Empire: Buildings of the Raj (by Jan Morris with photographs by Simon Winchester)

- 1983 – Prison Diary: Argentina

- 1984 – Their Noble Lordships: Class and Power in Modern Britain

- 1985 – Outposts: Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire (also known as The Sun Never Sets)

- 1988 – Korea, A Walk Through the Land of Miracles — Korea

- 1991 – Pacific Rising: The Emergence of a New World Culture

- 1992 – Hong Kong: Here Be Dragons (by Rich Browne, James Marshall and Simon Winchester)

- 1992 – Pacific Nightmare: How Japan Starts World War III : A Future History (novel)

- 1995 – Small World: A Global Photographic Project, 1987–94 (by Martin Parr and Simon Winchester), Dewi Lewis, ISBN 1-899235-05-1

- 1996 – The River at the Center of the World: A Journey Up the Yangtze, and Back in Chinese Time — the Yangtze

- 1998 – The Surgeon of Crowthorne: A Tale of Murder, Madness and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (Published in the US as The Professor and the Madman) – Dr. William Chester Minor and Sir James Murray

- 1999 – The Fracture Zone: A Return To The Balkans

- 2001 – The Map That Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology — the work of geologist William Smith

- 2003 – The Meaning of Everything — the making of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED)

- 2003 – Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded — the 27 August, 1883 eruption of Krakatoa

- 2004 – Simon Winchester's Calcutta (a collection of writings about the Indian city, edited with son Rupert)

- 2005 – A Crack in the Edge of the World: America and the Great California Earthquake of 1906 — the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

- 2008 – The Man Who Loved China — the life of Joseph Needham (title of the UK edition: Bomb, Book & Compass)

- 2010 – Atlantic: A Vast Ocean of a Million Stories. HarperCollins, 2010. ISBN 978-0-00-734137-5 (Alternative title: Atlantic: The Biography of an Ocean) — the Atlantic Ocean

- 2011 – The Alice Behind Wonderland — Alice Liddell

- 2013 – The Men Who United the States: America's Explorers, Inventors, Eccentrics and Mavericks, and the Creation of One Nation, Indivisible

Honours

Winchester was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire for "services to journalism and literature" in Queen Elizabeth II's New Year Honours list of 2006.

Winchester was named an honorary fellow at St. Catherine's College, Oxford in October 2009.[20]

Winchester received an honorary degree from Dalhousie University in October 2010.[21]

See also

- 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

- Krakatoa

- James Murray (lexicographer)

- Oxford English Dictionary

- William Chester Minor

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Simon Winchester Bio". Simon Winchester.com. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "My Turn: Simon Winchester on Becoming an American Citizen". newsweek.com. 26 June 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Winchester Simon – Bio of Winchester Simon – AEI Speakers Bureau". AEI Speakers Bureau. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ↑ "BookPage Interview August 2001: Simon Winchester". Bookpage.com. August 2001. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ↑ "Simon Winchester – Annotated Bibliography". San Jose State University. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ↑ Winchester, Simon (31 January 1972). "13 killed as paratroops break riot". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ Hoggart, Simon (22 July 1972). "11 die in Belfast hour of terror". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ McCann, Eamonn (1972). "3: The Press & The British Army". The British Press and Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland Socialist Research Centre. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ Pick, Hella (9 August 1974). "Dignity in the last goodbye". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Simon Winchester". ContemporaryWriters.com. 2004. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ "Travel Writers: Simon Winchester". Rolf Pott's Vagabonding. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ↑ "Best Sellers Plus". New York Times. 17 January 1999. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ↑ Dempsey, John (26 April 1999). "USA's working-class soap will bow in early evening". Variety. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ↑ Dargis, Manohla. "Movies: About The Professor and the Madman". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Best Sellers". New York Times. 9 September 2001. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ↑ "Best Sellers". New York Times. 25 August 2002. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ↑ "Best Sellers". New York Times. 6 November 2005. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ↑ "About the Book – The Man Who Loved China". HarperCollins. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ↑ "Simon Winchester Writer, Broadcaster and Traveler". Simon Winchester.com. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ↑ "Academic Staff". St Catherine's College. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ↑ "Simon Winchester". Dalhousie University Registrar. 8 October 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

External links

- Official website

- Interview on Natural and Unnatural Disasters (audio) by Counterpoint Radio, Marcus W. Orr Center for the Humanities, University of Memphis

- Interview about Bomb, Book & Compass – The Life of Joseph Needham (transcript) by Ramona Koval, The Book Show, ABC Radio National, 3 October 2008

- Interview about The Map That Changed the World by Powell's Books, 10 October 2006

- Simon Winchester at British Council: Literature

- Simon Winchester: Annotated Bibliography — comprehensive bibliography of articles, essays, and all of Winchester's books

- "Simon Winchester's Smooth Forked Tongue", David Martin, 26 December 2005

- Interview about The Atlantic by Claudia Cragg, KGNU radio, 2 December 2010

- Interview about The Professor and the Madman by Booknotes, C-SPAN, 8 November 1998

- The Bat Segundo Show (radio interviews): 28 December 2006 (42 minutes) and 26 November 2013 (51 minutes),

- Interview of Winchester by In Depth, C-SPAN, 1 August 2004

- Q&A with Winchester about Atlantic by C-SPAN, 26 October 2011

- Simon Winchester at Library of Congress Authorities, with 34 catalogue records

|