William R. King

| William R. King | |

|---|---|

| |

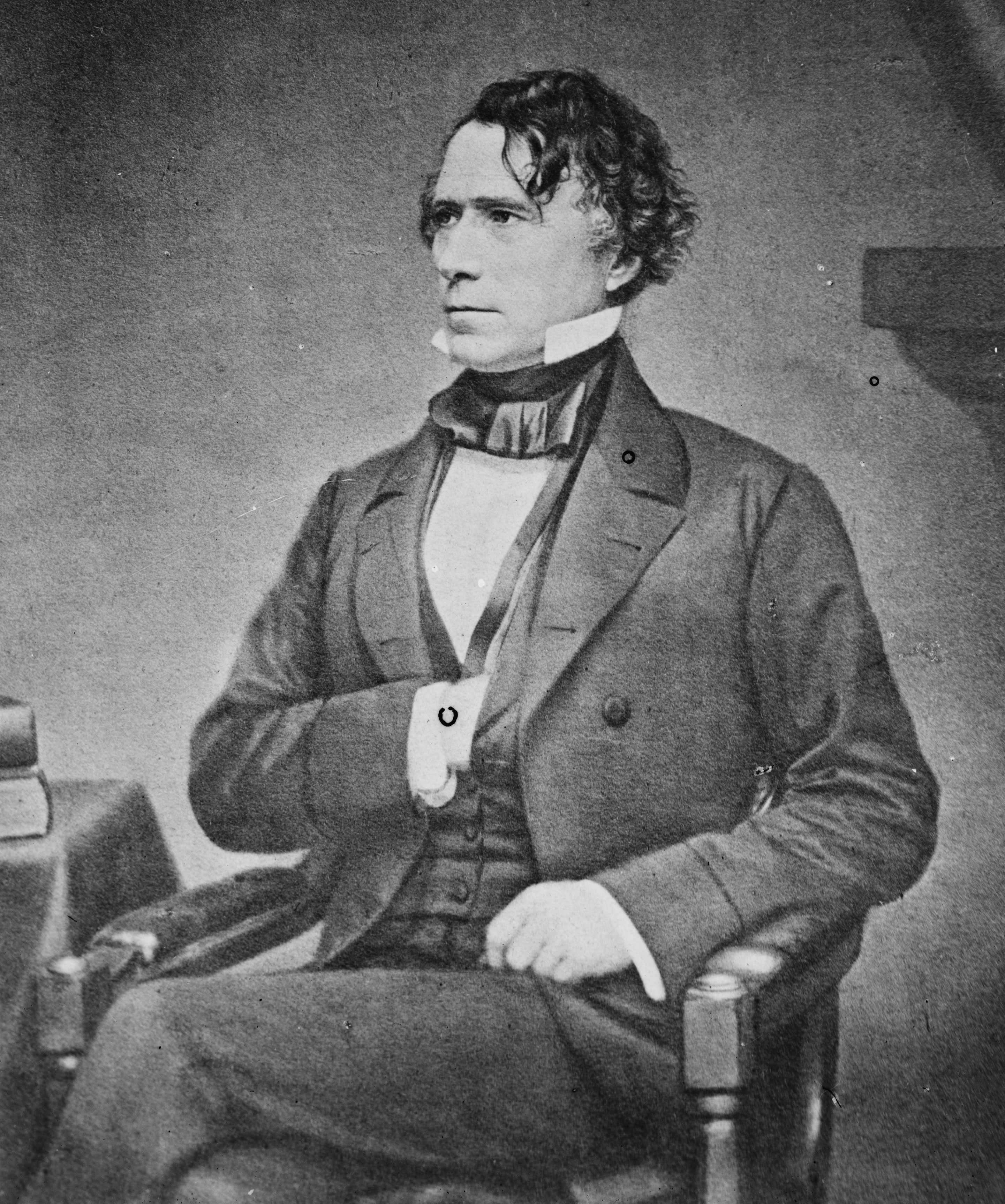

| Portrait of King, painted by George Cooke in 1839. | |

| 13th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1853 – April 18, 1853 | |

| President | Franklin Pierce |

| Preceded by | Millard Fillmore |

| Succeeded by | John C. Breckinridge |

| President pro tempore of the United States Senate | |

| In office May 6, 1850 – December 20, 1852 | |

| Preceded by | David Rice Atchison |

| Succeeded by | David Rice Atchison |

| In office July 1, 1836 – March 4, 1841 | |

| Preceded by | John Tyler |

| Succeeded by | Samuel L. Southard |

| United States Minister to France | |

| In office 1844–1846 | |

| Preceded by | Lewis Cass |

| Succeeded by | Richard Rush |

| United States Senator from Alabama | |

| In office December 14, 1819 – April 15, 1844 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Dixon Hall Lewis |

| In office July 1, 1848 – December 20, 1852 | |

| Preceded by | Arthur P. Bagby |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Fitzpatrick |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from North Carolina's 5th district | |

| In office March 4, 1811 – November 4, 1816 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Kenan |

| Succeeded by | Charles Hooks |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Rufus DeVane King April 7, 1786 Sampson County, North Carolina |

| Died | April 18, 1853 (aged 67) Selma, Dallas County, Alabama |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Alma mater | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

| Signature | |

William Rufus DeVane King (April 7, 1786 – April 18, 1853) was an American politician and diplomat. He was the 13th Vice President of the United States for about six weeks in 1853 before his death. Earlier he had been elected as a U.S. Representative from North Carolina and a Senator from Alabama. He also served as Minister to France.

A Democrat, he was a Unionist and his contemporaries considered him to be a moderate on the issues of sectionalism, slavery, and westward expansion that contributed to the American Civil War. He helped draft the Compromise of 1850.[1] He is the only United States executive official to take the oath of office on foreign soil. King died of tuberculosis after 45 days in office. With the exceptions of John Tyler and Andrew Johnson—both of whom succeeded to the Presidency—he is the shortest-serving Vice President.

King was the only Vice President from Alabama and, as such, held the highest political office of any Alabamian in American history.

Early life

King was born in Sampson County, North Carolina, to William King and Margaret deVane. His family was large, wealthy and well-connected. He graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1803, where he was also a member of the Philanthropic Society. Admitted to the bar in 1806 after reading the law with an established firm, he began practice in Clinton, North Carolina. King was an ardent and prominent Freemason, having been Elected on 15 December 1807, Entered on 17 December 1807, Passed on 3 May 1809, and Raised on 15 December 1810. He was a member of Phoenix Lodge No. 8, A.F. & A.M., Fayetteville, North Carolina.

Political career

King quickly entered politics and was elected as a member of the North Carolina House of Commons from 1807 to 1809, and city solicitor of Wilmington, North Carolina in 1810. He was elected to the Twelfth, Thirteenth and Fourteenth Congresses, serving from March 4, 1811 until November 4, 1816, when he resigned to take a federal appointment. King was appointed as Secretary of the Legation to William Pinkney at Naples, Italy, and later at St. Petersburg, Russia.

When he returned to the United States in 1818, King joined the westward migration to the Deep South, purchasing property at what would later be known as King's Bend on the Alabama River in Dallas County, Alabama, part of the Black Belt. It was between present-day Selma and Cahaba. He developed a large cotton plantation based on slave labor, calling the property Chestnut Hill. King and his relatives, as others moved to Alabama, together formed one of the largest slaveholding families in the state, collectively owning as many as 500 slaves.

Politics

King was a delegate to the convention which organized the Alabama state government. Upon the admission of Alabama as a State in 1819, he was elected by the legislature as a Democratic-Republican to the United States Senate. He was reelected as a Jacksonian in 1822, 1828, 1834, and 1841, serving from December 14, 1819, until April 15, 1844, when he resigned. He served as President pro tempore of the United States Senate during the 24th through 27th Congresses. King was Chairman of the Committee on Public Lands and the Committee on Commerce.

He was appointed as Minister to France from 1844 to 1846. After his return, King was appointed and subsequently elected as a Democrat to the Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Arthur P. Bagby; he began serving on July 1, 1848.

During the conflicts leading up to the Compromise of 1850, King supported the Senate's gag rule against debate on antislavery petitions and opposed proposals to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia, which was administered by Congress.[2] King supported a conservative, pro-slavery position, arguing that the Constitution protected the institution of slavery in both the Southern states and the federal territories. He opposed both the abolitionists' efforts to abolish slavery in the territories as well as the Fire-Eaters' calls for Southern secession.[2]

On July 11, 1850, two days after the death of President Zachary Taylor, King was appointed President pro tempore of the Senate. Because of the vacancy in the vice-presidential office, due to succession rules he was first in the line of succession to the U.S. Presidency. King served until resigning on December 20, 1852, due to poor health (he was found to have tuberculosis). He served also as Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations and Committee on Pensions.

Relationship with James Buchanan

While King may have been asexual or celibate, there are many indicators that suggest he was homosexual. The argument has been put forward by Shelley Ross, biographer Jean Baker,[3] James W. Loewen, and Robert P. Watson.

The source of this interest has been King's close and intimate relationship with President James Buchanan. The two men lived together in a Washington boardinghouse for 10 years from 1834 until King's departure for France in 1844, after which point they never again resided together. King referred to the relationship as a "communion".,[4] and the two often attended social functions together. Contemporaries also noted the closeness. Andrew Jackson called them "Miss Nancy"[5] and "Aunt Fancy" (the former being a 19th-century euphemism for an effeminate man[6]), while Aaron V. Brown referred to King as Buchanan's "better half".[7][8] James Loewen has described Buchanan and King as "siamese twins".[9]

Buchanan adopted King's mannerisms and romanticised view of southern culture. Both had strong political ambitions and in 1844 they planned to run as president and vice president. They spent some time apart while King was on overseas missions in France, and their letters remain cryptic, avoiding revealing any personal feelings at all. In May 1844, Buchanan wrote to Cornelia Roosevelt, "I am now 'solitary and alone,' having no companion in the house with me. I have gone a wooing to several gentlemen, but have not succeeded with any one of them. I feel that it is not good for man to be alone, and [I] should not be astonished to find myself married to some old maid who can nurse me when I am sick, provide good dinners for me when I am well, and not expect from me any very ardent or romantic affection."[4]

King became ill in 1853 and died shortly of tuberculosis after Pierce's inauguration, four years before Buchanan became President. Buchanan described him as "among the best, the purest and most consistent public men I have known."[4] While some of their correspondence does not survive, the length and intimacy of surviving letters illustrate "the affection of a special friendship."

Vice Presidency and death

King was elected Vice President of the United States on the Democratic ticket with Franklin Pierce in 1852. By a special act of Congress, he took the oath of office on March 24, 1853 in Cuba,[10][11] twenty days after he became Vice President.[2] He had gone to John Chartrand's La Ariadne plantation in Matanzas because of ill health, and the unusual inauguration took place on foreign soil because it was believed that King, then known to be terminally ill with tuberculosis, would not live much longer.[1] Although he did not take the oath until 20 days after the inauguration day, he was legally considered to be the Vice President during those three weeks.[2]

Shortly afterward, King returned to his Chestnut Hill plantation where he died within two days. He was interred in a vault on the plantation and later reburied in Selma's Live Oak Cemetery. King never came to Washington, D.C. or carried out any duties of the office during his term.[12] The U.S. Senate displays a bust of King in its collection, even though he never presided over a legislative session as Vice President.[13]

Following King's death, the office of Vice President was vacant for four years until March 4, 1857, when John C. Breckinridge was inaugurated. In accordance with the Presidential Succession Act of 1792, the President pro tempore of the Senate was next in order of succession to President Pierce from 1853 to 1857.

Legacy and honors

- In 1852 the Oregon Territory named King County for him, as well as Pierce County after President-elect Pierce. These counties became part of Washington Territory when it was created the following year. Washington did not become a state until 1889; much later, King County amended its designation and its logo to honor Martin Luther King, Jr.. The county took its action after passing an ordinance;[14] it was later reaffirmed by statutory action (SB 5332, April 19, 2005) of the State of Washington.[15]

- As the Kingdome (1976–2000), Seattle's baseball-football domed stadium, was built when King County was still named in honor of William R. King, this major league sports arena can be said to have been indirectly named after the vice president.

- The King Residence Quadrangle at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, his alma mater, is named for him. It is the site of Mangum, Manly, Ruffin and Grimes house residences.

- An 1830 portrait of King is held at New East Hall in the Philanthropic Chambers by The Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies, a debating society which he had joined during college.

- King was a co-founder of (and named) Selma, a town on the Alabama River town after the Ossianic poem The Songs of Selma.[1] After his death, city officials and some of King's family wanted to move his body to Selma. Other family members wanted his body to remain at Chestnut Hill. In 1882, the Selma City Council appointed a committee to select a new plot for King's body. After 29 years, his remains were removed from his plantation and reinterred in the city's Live Oak Cemetery under an elaborate white marble mausoleum erected by the city.[16]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Daniel Fate Brooks (2003). "The Faces of William R. King". Alabama Heritage (University of Alabama, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Alabama Department of Archives and History) 69 (Summer): 14–23. Retrieved 2013-05-03.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 United States Senate: William Rufus King, 13th Vice President (1853)

- ↑ Jean H. Baker, James Buchanan: The American Presidents Series: The 15th President, 1857–1861, 2004, page 26

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Robert Watson, Affairs of State: The untold story of presidential love sex and scandal, 1789-1900, Plymouth, 2012

- ↑ Bill Kelter, Veeps, 2008, page 71

- ↑ The Wordsworth Book of Euphemisms by Judith S. Neaman and Carole G. Silver (Wordsworth Editions Ltd., Hertfordshire)

- ↑ Baker (2004), p. 75.

- ↑ Wesley O. Hagood, Presidential Sex: From the Founding Fathers to Bill Clinton, 1998, page 41

- ↑ James W. Loewen, Lies Across America: What American Historic Sites Get Wrong, 2007, page 342

- ↑ Benson Lossing, ed. (1907). Harper's Encyclopedia of United States History. Harper & Brothers. p. 195. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Vice Presidential Inaugurations". Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ↑ Patrick, John J.; Pious, Richard M.; Ritchie, Donald A., ed. (2001). The Oxford Guide to the United States Government. Oxford University Press. p. 363. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Busts of Vice Presidents of the United States". Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Motion No. 6461 (King County, WA)". King County, WA. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ "State law changed to rename King County". King County, Washington. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Jaffee, Al (1979). The Ghoulish Book of Weird Records. Signet. pp. 136–140. ISBN 0-451-08614-7.

External links

- William R. King at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Who is William Rufus King?

- "Obituary addresses on the occasion of the death of the Hon. William R. King, of Alabama, vice-president of the United States : delivered in the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States, eighth of December, 1853", Archives

- William R. King at Find a Grave

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: William R. King |

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||

|