Wild Bactrian camel

| Wild Bactrian Camel | |

|---|---|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Camelidae |

| Genus: | Camelus |

| Species: | C. ferus |

| Binomial name | |

| Camelus ferus Przewalski, 1878 | |

| |

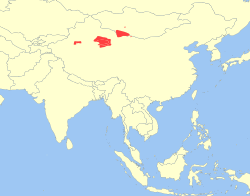

| Geographic range | |

The wild Bactrian camel (Camelus ferus) is called havtagai ("flat") in Mongolian. It is closely related to the domesticated Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus): they are both large, even-toed ungulates native to the steppes of central Asia, with double hump (small and pyramid-shaped).[1] Most modern experts tend to describe it as a separate species from the domesticated Bactrian camel.[2] It is restricted in the wild to remote regions of the Gobi and Taklamakan Deserts of Mongolia and Xinjiang. A few wild Bactrians still roam the Mangystau Province of southwest Kazakhstan and the Kashmir valley in India. They are also found along rivers in Siberia: they migrate there in winter.[3] Their habitat is in arid plains and hills where water sources are scarce and there is very little vegetation; shrubs are their food source.[1]

Differences between Camelus ferus and Camelus bactrianus

Until recently the Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) was considered to be a domesticated form of the wild Bactrian camel. Modern experts describe it a separate species due to the fact that the Wild Bactrian camel has 3 more chromosome pairs than the domesticated Camel – see, for example: J. Hare (2008) and D. T. Potts (2004).

The wild Bactrian camel has been described as "relatively small, lithe, and slender-legged, with very narrow feet and a body that looks laterally compressed."[4]"Zoological opinion nowadays tends to favour the idea that C. bactrianus and dromedarius are descendants of two different sub-species of C. ferus (Peters and von den Driesch 1997: 652) and there is no evidence to suggest that the original range of C. ferus included those parts of Central Asia and Iran where some of the earliest Bactrian remains have been found."[4]

"The wool of C. ferus is "shorter and sparser than that of domestic animals" (Schaller 1998: 152) and its colour is always sandy (Bannikov 1976: 398). And most notably, C. ferus has "low, pointed, cone-shaped humps—usually about half the size of those of the domestic camel in fair condition” (Bannikov 1976: 398)."[5]Like its close relative, the domesticated Bactrian camel, it is one of the few mammals able to eat snow to provide itself with liquids in the winter.[6] It can also survive on water even saltier than seawater – which no other large mammal in the world, including the domestic Bactrian camel, can tolerate.[7]

"The wild Bactrian camel differs from the domestic Bactrian in a number of ways – smaller, more conical humps, flatter skull (havtagai, the Mongolian name for a wild Bactrian camel, means 'flat-head'), a different shape of foot – but the outstanding difference is genetic. Its DNA varies from that of the domestic Bactrian by 3 per cent. Our genetic variation from a chimpanzee is 5 per cent."[8]

Habitat

Their habitat is in arid plains and hills where water sources are scarce and there is very little vegetation: shrubs are their food source.[1]

Wild camels travel over long distances, seeking water in places close to mountains where springs are found, and hill slopes covered in snow could provide some moisture in winter. Size of the herds varies from 100 camels close hills but generally of 2-15 members in a group; this is reported to be due to arid environment and heavy poaching. As against about 2.5 million domestic Bactrian camels reported in Central Asia, the statistics for the wild Bactrian are limited to three pockets in Mongolia and China;[1] about 650 in the Gobi desert in north-west China and 450 in the Mongolian desert[9]

In ancient times, wild Bactrian camels were seen from the great bend of the Yellow River extending west to the Southern Mongolia deserts and further to Northwest China and central Kazakhstan. In the 1800s, due to hunting for its meat and hide, its presence was noted in remote areas of the Gobi and Taklimakan Deserts in Mongolia and China. In the 1920s, only remnant populations were recorded in Mongolia and China.[1]

Description

The habitats of the Bactrian camel have widely varying temperatures: the summer temperature ranges from 60-70 deg C[citation needed] (140 – 160 deg F) and winter temperature a low of -30 deg C (-22 deg F). Their long, narrow slit-like nostrils and thick eyelashes (double row of long eyelashes), and the ears with hairs) provide protection against desert sandstorms. They have tough undivided soles with two large toes that spread wide apart, and a horny layer which enables them to walk on rough and hot stony or sandy terrain. Their body hair, thick and shaggy, changes colour of light brown or beige colour during winter.[1][10] The legend that camels storing water in their stomachs is a misconception: though they have capacity to conserve water they cannot survive without water for long periods.[1]

They are fully migratory and widely scattered, and move in groups of 6 to 20, depending on the food available, with a single adult male in the lead, and assemble near water points where larger groups can also be seen. Their population density is reported to be as low as 5 per 100 km2. Their lifespan is about 40 years and they breed during winter with an overlap into the rainy season. Females produce offspring starting at age 5, and thereafter in a cycle of 2 years.[10]

Status

The wild Bactrian camel is more critically endangered than the Giant Panda. John Hare in his 2009 book estimated that there were only about 900 of them left in the world.[11] The London Zoological Society recognizes it as the eighth most endangered large mammal in the world,[8] and it is on the Critically Endangered List. Observations made during five field expeditions starting in 1993 by John Hare and the United Kingdom-based Wild Camel Protection Foundation (WCPF) suggest that the surviving populations may be facing an 80% decline within the next three generations. The animal can survive by drinking a saltwater slush that is unpalatable to domestic camel species. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) its status was critical in the 1960s and gradually declined to Critically Endangered (Criteria: A3de + 4ade) status in 2000-2004 (IUCN 2004).[1] Research carried out by the WCPF in association with John Hare from 1993 onwards indicated that this species of camel could suffer an 80% reduction in numbers in the next 30 years.[12]

Threats

Wild Bactrians face many threats. The main threat is hunting: in the Gobi Reserve Area, 25 to 30 camels are reported to be poached for domestic use every year, and about 20 in the Arjin Shan Lop Nur Nature Sanctuary. Other threats include land mines laid in the salt water springs,[3] scarcity of access to water (oases), attack by wolves, migration into domestic areas in search of grazing land, hybridization with domestic Bactrians (resulting in loss of their genetic distinctiveness), toxic effluent releases from illegal mining, redesignation of wildlife areas as industrial zones, and sharing grazing areas with domestic animals.[13]

Conservation

Several actions have been initiated by the Governments of China and Mongolia to conserve this species of mammal such as the ecosystem-based management programme; two programmes instituted in this respect are the Great Gobi Reserve A (funded by UNEP & Global Environment Facility of the order of $1,650,000 in 1979[3]) in Mongolia set up in 1982, and the Arjin Shan Lop Nur Nature Reserve (funded by UNEP and Global Environment Facility to the extent of $750,000[3]), on the border of Kum Tagh sand dunes in the Tibetan mountains reserve, established in China in 2000.[10] The Wild Camel Protection Foundation, the only such charity of its kind, has as its main goal conservation of the wild Bactrian in its natural desert environment to ensure that they do not get listed in the extinct category of IUCN.[3][9] The actions taken by the various organizations, motivated and supported by IUCN and WCPF are: Establishment of more nature reserves (in China and Mongolia) for their conservation, and breeding them in captivity, 15 animals in captivity, (as females can give two litters every two years which may not happen when they are in the wild) to prevent extinction.[13] The captive breeding initiated by WCPF in 2003 is the Zakhyn-Us Sanctuary in Mongolia, where the initial programme of breeding last non-hybridised herds of Bactrian camels has proved a success with the birth of several calves.[10]

The wild Bactrian camel is also being considered for introduction at Pleistocene Park in Northern Siberia as a proxy for extinct Pleistocene camel species.[14][15] If this proves feasible, it would increase their geographic range considerably, adding a safety margin to their survival.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 "Animal Info - Endangered Animals: Camelus bactrianus (Camelus bactrianus ferus)". Animal Information Organization. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ See, for example: J. Hare (2008) and D. T. Potts (2004)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "New' camel lives on salty water". BBC Nature. 6 February 2001. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Potts (2004), p. 145.

- ↑ Potts (2004), p. 146.

- ↑ Video showing wild Bactrian camels eating snow.

- ↑ Hare (2009), pp. 6, 28.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hare (2009), p. 197.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Help Us". Wild Camel Protection Foundation. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "13. Bactrian Camel (Camelus ferus)". Evolutionarily Distinct & Globally Endangered. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ Hare (2009), pp. 6, 22.

- ↑ "Wild Bactrian Camels Critically Endangered, Group Says". National geographic Service News. 3 December 2002. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Camelus ferus". IUCN. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ Martin W. Lewis (12 April 2012). "Pleistocene Park: The Regeneration of the Mammoth Steppe?". GeoCurrents. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ↑ Lidia Kruglova (2 May 2011). "Pleistocene Park: so far without mammoths". Voice of Russia. Article also to be found in www.pleistocenepark.ru/en/ – Media about us. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Bulliet, Richard W. (1975): The Camel and the Wheel. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press.

- Hare, J. 2008. Camelus ferus. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 22 October 2012.

- Hare (2009). Mysteries of the Gobi: Searching for Wild Camels and Lost Cities in the Heart of Asia. John Hare. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-512-8.

- Potts, D. T. 2004. “Camel Hybridization and the Role of Camelus Bactrianus in the Ancient Near East.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 47 (2004): 143-165.

- EDGE of Existence "(Bactrian camel)" Saving the World's most Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) species

- BBC – Discovery of camels in the Gashun Gobi region

External links

- "Camelus ferus" on the ICUN Redlinst

- National Geographic – Wild Bactrian Camels Critically Endangered

- Wild Camel Protection Foundation

- Journalist Aaron Sneddon Bactrian Camels at the Highland Wildlife Park Scotland

- Video showing Wild Bactrian camels eating snow.