Wigner quasiprobability distribution

- See also Wigner distribution, a disambiguation page.

The Wigner quasiprobability distribution (also called the Wigner function or the Wigner–Ville distribution after Eugene Wigner and Jean-André Ville) is a quasiprobability distribution. It was introduced[2] by Eugene Wigner in 1932 to study quantum corrections to classical statistical mechanics. The goal was to link the wavefunction that appears in Schrödinger's equation to a probability distribution in phase space.

It is a generating function for all spatial autocorrelation functions of a given quantum-mechanical wavefunction ψ(x). Thus, it maps[3] on the quantum density matrix in the map between real phase-space functions and Hermitian operators introduced by Hermann Weyl in 1927,[4] in a context related to representation theory in mathematics (cf. Weyl quantization in physics). In effect, it is the Weyl–Wigner transform of the density matrix, so the realization of that operator in phase space. It was later rederived by Jean Ville in 1948 as a quadratic (in signal) representation of the local time-frequency energy of a signal,[5] effectively a spectrogram.

In 1949, José Enrique Moyal, who had derived it independently, recognized it as the quantum moment-generating functional,[6] and thus as the basis of an elegant encoding of all quantum expectation values, and hence quantum mechanics, in phase space (cf. phase space formulation). It has applications in statistical mechanics, quantum chemistry, quantum optics, classical optics and signal analysis in diverse fields such as electrical engineering, seismology, time–frequency analysis for music signals, spectrograms in biology and speech processing, and engine design.

Relation to classical mechanics

A classical particle has a definite position and momentum, and hence it is represented by a point in phase space. Given a collection (ensemble) of particles, the probability of finding a particle at a certain position in phase space is specified by a probability distribution, the Liouville density. This strict interpretation fails for a quantum particle, due to the uncertainty principle. Instead, the above quasiprobability Wigner distribution plays an analogous role, but does not satisfy all the properties of a conventional probability distribution; and, conversely, satisfies boundedness properties unavailable to classical distributions.

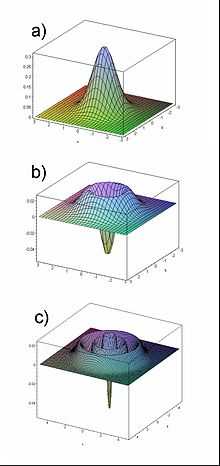

For instance, the Wigner distribution can and normally does go negative for states which have no classical model—and is a convenient indicator of quantum mechanical interference. Smoothing the Wigner distribution through a filter of size larger than ħ (e.g., convolving with a phase-space Gaussian to yield the Husimi representation, below), results in a positive-semidefinite function, i.e., it may be thought to have been coarsened to a semi-classical one. (Specifically, since this convolution is invertible, in fact, no information has been sacrificed, and the full quantum entropy has not increased, yet. However, if this resulting Husimi distribution is then used as a plain measure in a phase-space integral evaluation of expectation values without the requisite star product of the Husimi representation, then, at that stage, quantum information has been forfeited and the distribution is a semi-classical one, effectively. That is, depending on its usage in evaluating expectation values, the very same distribution may serve as a quantum or a classical distribution function.)

Regions of such negative value are provable (by convolving them with a small Gaussian) to be "small": they cannot extend to compact regions larger than a few ħ, and hence disappear in the classical limit. They are shielded by the uncertainty principle, which does not allow precise location within phase-space regions smaller than ħ, and thus renders such "negative probabilities" less paradoxical.

Definition and meaning

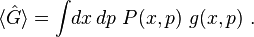

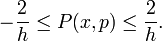

The Wigner distribution P(x,p) is defined as:

where ψ is the wavefunction and x and p are position and momentum but could be any conjugate variable pair (i.e. real and imaginary parts of the electric field or frequency and time of a signal). Note that it may have support in x even in regions where ψ has no support in x ("beats").

It is symmetric in x and p,

where φ is the Fourier transform of ψ.

In 3D,

In the general case, which includes mixed states, it is the Wigner transform of the density matrix,

This Wigner transformation (or map) is the inverse of the Weyl transform, which maps phase-space functions to Hilbert-space operators, in Weyl quantization. Thus, the Wigner function is the cornerstone of quantum mechanics in phase space.

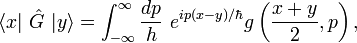

In 1949, José Enrique Moyal elucidated how the Wigner function provides the integration measure (analogous to a probability density function) in phase space, to yield expectation values from phase-space c-number functions g(x,p) uniquely associated to suitably ordered operators Ĝ through Weyl's transform (cf. Weyl quantization and property 7 below), in a manner evocative of classical probability theory.

Specifically, an operator's Ĝ expectation value is a "phase-space average" of the Wigner transform of that operator,

Mathematical properties

1. P(x, p) is real

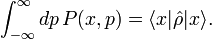

2. The x and p probability distributions are given by the marginals:

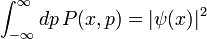

If the system can be described by a pure state, one gets

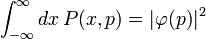

If the system can be described by a pure state, one gets

. If the system can be described by a pure state, one has

. If the system can be described by a pure state, one has

- Typically the trace of the density matrix ρ̂ is equal to 1.

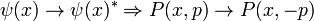

3. P(x, p) has the following reflection symmetries:

- Time symmetry:

- Space symmetry:

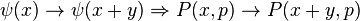

4. P(x, p) is Galilei-covariant:

- It is not Lorentz covariant.

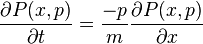

5. The equation of motion for each point in the phase space is classical in the absence of forces:

In fact, it is classical even in the presence of harmonic forces.

6. State overlap is calculated as:

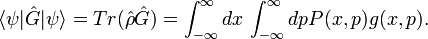

7. Operator expectation values (averages) are calculated as phase-space averages of the respective Wigner transforms:

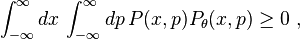

8. In order that P(x, p) represent physical (positive) density matrices:

for all pure states |θ〉.

9. By virtue of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, for a pure state, it is constrained to be bounded,

This bound disappears in the classical limit, ħ → 0. In this limit, P(x, p) reduces to the probability density in coordinate space x, usually highly localized, multiplied by δ-functions in momentum: the classical limit is "spiky". Thus, this quantum-mechanical bound precludes a Wigner function which is a perfectly localized delta function in phase space, as a reflection of the uncertainty principle.[7]

Evolution equation for Wigner function

The Wigner transformation is a general invertible transformation of an operator Ĝ on a Hilbert space to a function g(x,p) on phase space, and is given by

Hermitian operators map to real functions. The inverse of this transformation, so from phase space to Hilbert space, is called the Weyl transformation,

(not to be confused with another definition of the Weyl transformation).

The Wigner function P(x,p) discussed here is thus seen to be the Wigner transform of the density matrix operator ρ̂. Thus, the trace of an operator with the density matrix Wigner-transforms to the equivalent phase-space integral overlap of g(x, p) with the Wigner function.

The Wigner transform of the von Neumann evolution equation of the density matrix in the Schrödinger picture is Moyal's evolution equation for the Wigner function,

where H(x,p) is Hamiltonian and { {•, •} } is the Moyal bracket. In the classical limit ħ → 0, the Moyal bracket reduces to the Poisson bracket, while this evolution equation reduces to the Liouville equation of classical statistical mechanics.

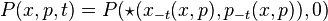

Strictly formally, in terms of quantum characteristics, the solution of

this evolution equation reads,  ,

where

,

where  and

and  are solutions of

so-called quantum Hamilton's equations, subject to initial conditions

are solutions of

so-called quantum Hamilton's equations, subject to initial conditions

and

and  , and where

, and where  composition is understood for all argument functions.

Since

composition is understood for all argument functions.

Since  -composition is thoroughly nonlocal (the "quantum probability fluid" diffuses, as observed by Moyal), vestiges of local trajectories

are normally barely discernible in the evolution of the Wigner distribution function.[8]

In the integral representation of ★-products, successive operations by them have been adapted to a phase-space path-integral, to solve this evolution equation for the Wigner function [9] (see also [10][11][12]).

-composition is thoroughly nonlocal (the "quantum probability fluid" diffuses, as observed by Moyal), vestiges of local trajectories

are normally barely discernible in the evolution of the Wigner distribution function.[8]

In the integral representation of ★-products, successive operations by them have been adapted to a phase-space path-integral, to solve this evolution equation for the Wigner function [9] (see also [10][11][12]).

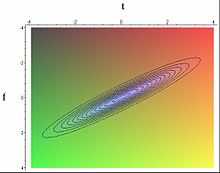

| Examples of the Wigner function time-evolutions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

Classical limit

The Wigner function allows one to study the classical limit, offering a comparison of the classical and quantum dynamics in phase space.[13][14]

It has recently been suggested that the Wigner function approach can be viewed as a quantum analogy to the operatorial formulation of classical mechanics introduced in 1932 by Bernard Koopman and John von Neumann: the time evolution of the Wigner function approaches, in the limit ħ → 0, the time evolution of the Koopman–von Neumann wavefunction of a classical particle.[15][16]

The Wigner function in relation to other interpretations of quantum mechanics

It has been shown that the Wigner quasiprobability distribution function can be regarded as an ħ-deformation of another phase space distribution function that describes an ensemble of de Broglie–Bohm causal trajectories.[17] Basil Hiley has shown that the quasi-probability distribution may be understood as the density matrix re-expressed in terms of a mean position and momentum of a "cell" in phase space, and the de Broglie–Bohm interpretation allows one to describe the dynamics of the centers of such "cells".[18][19]

There is a close connection between the description of quantum states in terms of the Wigner function and a method of quantum states reconstruction in terms of mutually unbiased bases.[20]

Uses of the Wigner function outside quantum mechanics

- In the modelling of optical systems such as telescopes or fibre telecommunications devices, the Wigner function is used to bridge the gap between simple ray tracing and the full wave analysis of the system. Here p/ħ is replaced with k = |k|sinθ ≈ |k|θ in the small angle (paraxial) approximation. In this context, the Wigner function is the closest one can get to describing the system in terms of rays at position x and angle θ while still including the effects of interference. If it becomes negative at any point then simple ray-tracing will not suffice to model the system.

- In signal analysis, a time-varying electrical signal, mechanical vibration, or sound wave are represented by a Wigner function. Here, x is replaced with the time and p/ħ is replaced with the angular frequency ω = 2πf, where f is the regular frequency.

- In ultrafast optics, short laser pulses are characterized with the Wigner function using the same f and t substitutions as above. Pulse defects such as chirp (the change in frequency with time) can be visualized with the Wigner function. See Figure 7.

- In quantum optics, x and p/ħ are replaced with the X and P quadratures, the real and imaginary components of the electric field (see coherent state). The plots in Figure 1 are of quantum states of light.

Measurements of the Wigner function

- Tomography

- Homodyne detection

- FROG Frequency-resolved optical gating

Other related quasiprobability distributions

The Wigner distribution was the first quasiprobability distribution to be formulated, but many more followed, formally equivalent and transformable to and from it (viz. Transformation between distributions in time–frequency analysis). As in the case of coordinate systems, on account of varying properties, several such have with various advantages for specific applications:

- Glauber P representation

- Husimi Q representation

Nevertheless, in some sense, the Wigner distribution holds a privileged position among all these distributions, since it is the only one whose requisite star product drops out (integrates out by parts to effective unity) in the evaluation of expectation values, as illustrated above, and so can be visualized as a quasiprobability measure analogous to the classical ones.

Historical note

As indicated, the formula for the Wigner function was independently derived several times in different contexts. In fact, apparently, Wigner was unaware that even within the context of quantum theory, it had been introduced previously by Heisenberg and Dirac,[21] albeit purely formally: these two missed its significance, and that of its negative values, as they merely considered it as an approximation to the full quantum description of a system such as the atom. (Incidentally, Dirac would later become Wigner's brother-in-law, marrying his sister Manci.) Symmetrically, in most of his legendary 18-month correspondence with Moyal in the mid-1940s, Dirac was unaware that Moyal's quantum-moment generating function was effectively the Wigner function, and it was Moyal who finally brought it to his attention.[22]

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ Curtright, T.L., Time-dependent Wigner Functions

- ↑ E.P. Wigner, "On the quantum correction for thermodynamic equilibrium", Phys. Rev. 40 (June 1932) 749–759. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.40.749

- ↑ H.J. Groenewold, "On the Principles of elementary quantum mechanics",Physica,12 (1946) 405–460. doi:10.1016/S0031-8914(46)80059-4

- ↑ H. Weyl, Z. Phys. 46, 1 (1927). doi:10.1007/BF02055756; H. Weyl, Gruppentheorie und Quantenmechanik (Leipzig: Hirzel) (1928); H. Weyl, The Theory of Groups and Quantum Mechanics (Dover, New York, 1931).

- ↑ J. Ville, "Théorie et Applications de la Notion de Signal Analytique", Câbles et Transmission, 2, 61–74 (1948).

- ↑ J.E. Moyal, "Quantum mechanics as a statistical theory", Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 45, 99–124 (1949). doi:10.1017/S0305004100000487

- ↑ Curtright, T. L.; Zachos, C. K. (2012). "Quantum Mechanics in Phase Space". Asia Pacific Physics Newsletter 01: 37. doi:10.1142/S2251158X12000069.; C. Zachos, D. Fairlie, and T. Curtright, Quantum Mechanics in Phase Space ( World Scientific, Singapore, 2005) ISBN 978-981-238-384-6 .

- ↑ Quantum characteristics should not be confused with trajectories of the Feynman path integral, or trajectories of the de Broglie - Bohm theory. This three-fold ambiguity allows better understanding of the position of Niels Bohr, who, vigorously but counterproductively, opposed the notion of trajectory in the atomic physics. At the 1948 Pocono Conference, e.g., he said to Richard Feynman: "… one could not talk about the trajectory of an electron in the atom, because it was something not observable." ("The Beat of a Different Drum: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman", by Jagdish Mehra (Oxford, 1994, pp. 245-248)). Arguments of this kind were widely used in the past by Ernst Mach in his criticism of an atomic theory of physics and later, in the 1960's, by Geoffrey Chew, Tullio Regge and others to motivate replacing the local quantum field theory by the S-matrix theory. Today, statistical physics entirely based on atomistic concepts is included in standard courses, the S-matrix theory went out of fashion, while the Feynman path integral method has been recognized as the most efficient method in gauge theories.

- ↑ Leaf, B. (1968), "Weyl Transform in Nonrelativistic Quantum Dynamics", J. Math. Phys. 9, 769-781. doi:10.1063/1.1664640

- ↑ Sharan, P. (1979). "Star-product representation of path integrals". Physical Review D 20 (2): 414. Bibcode:1979PhRvD..20..414S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.20.414.

- ↑ Marinov, M. S. (1991), A new type of phase-space path integral, Phys. Lett. A153, 5.

- ↑ B. Segev: Evolution kernels for phase space distributions. In: M. A. Olshanetsky (ed.); Arkady Vainshtein (ed.) (2002). Multiple Facets of Quantization and Supersymmetry: Michael Marinov Memorial Volume. World Scientific. pp. 68–90. ISBN 978-981-238-072-2. Retrieved 26 October 2012. see especially section 5. "Path integral for the propagator" on pages 86-89

- ↑ See for example: Wojciech H. Zurek: Decoherence and the transition from quantum to classical - revisited, Los Alamos Science, 27, 2002, arXiv:quant-ph/0306072, pp. 15 ff.

- ↑ See for example: C. Zachos, D. Fairlie, T. Curtright: Quantum mechanics in phase space: an overview with selected papers, World Scientific, 2005

- ↑ Denys I. Bondar, Renan Cabrera, Dmitry V. Zhdanov, Herschel A. Rabitz: Wigner Function's Negativity Demystified arXiv:1202.3628v2 (quant-phys) (submitted February 2012, version of 3 November 2012)

- ↑ Renan Cabrera, Denys I. Bondar, Herschel A. Rabitz: Relativistic Wigner function and consistent classical limit for spin 1/2 particles, arXiv:1107.5139v2 (submitted on 26 July 2011, version of 22 August 2012)

- ↑ Nuno Costa Dias, Joao Nuno Prata, Bohmian trajectories and quantum phase space distributions, Physics Letters A vol. 302 (2002) pp. 261-272, doi:10.1016/S0375-9601(02)01175-1 arXiv:quant-ph/0208156v1 (submitted 26 August 2002)

- ↑ B. J. Hiley: Phase space descriptions of quantum phenomena, in: A. Khrennikov (ed.): Quantum Theory: Re-consideration of Foundations–2, pp. 267-286, Växjö University Press, Sweden, 2003 (PDF)

- ↑ B. Hiley: Moyal's characteristic function, the density matrix and von Neumann's idempotent (preprint)

- ↑ F.C. Khanna, P.A. Mello, M. Revzen, Classical and Quantum Mechanical State Reconstruction, arXiv:1112.3164v1 [quant-ph] (submitted December 14 2011)

- ↑ W. Heisenberg, "Über die inkohärente Streuung von Röntgenstrahlen", Physik. Zeitschr. 32, 737–740 (1931); P.A.M. Dirac, "Note on exchange phenomena in the Thomas atom", Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 26, 376–395 (1930). doi:10.1017/S0305004100016108

- ↑ Ann Moyal, (2006), "Maverick Mathematician: The Life and Science of J.E. Moyal," ANU E-press, 2006, ISBN 1-920942-59-9 , accessed by http://epress.anu.edu.au/maverick_citation.html

Further reading

- M. Levanda and V Fleurov, "Wigner quasi-distribution function for charged particles in classical electromagnetic fields", Annals of Physics, 292, 199–231 (2001). arXiv:cond-mat/0105137

External links

- Wigner function tutorial and Gallery of WFs, Institute for Quantum Information Science (IQIS), University of Calgary

- Quantum Optics Gallery

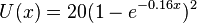

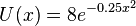

in

in

in atomic units (a.u.). The solid lines represent the

in atomic units (a.u.). The solid lines represent the

in atomic units (a.u.). The solid lines represent the

in atomic units (a.u.). The solid lines represent the